The question that matters for home batteries is not how much energy they store. The question is what happens when cells fail.

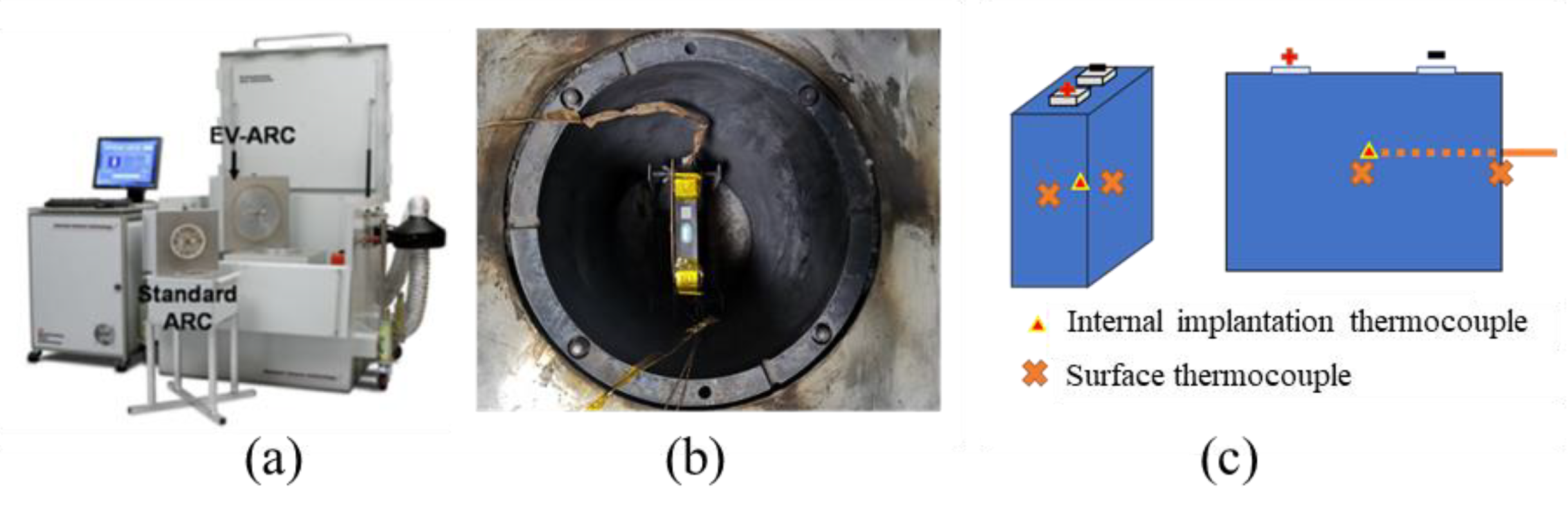

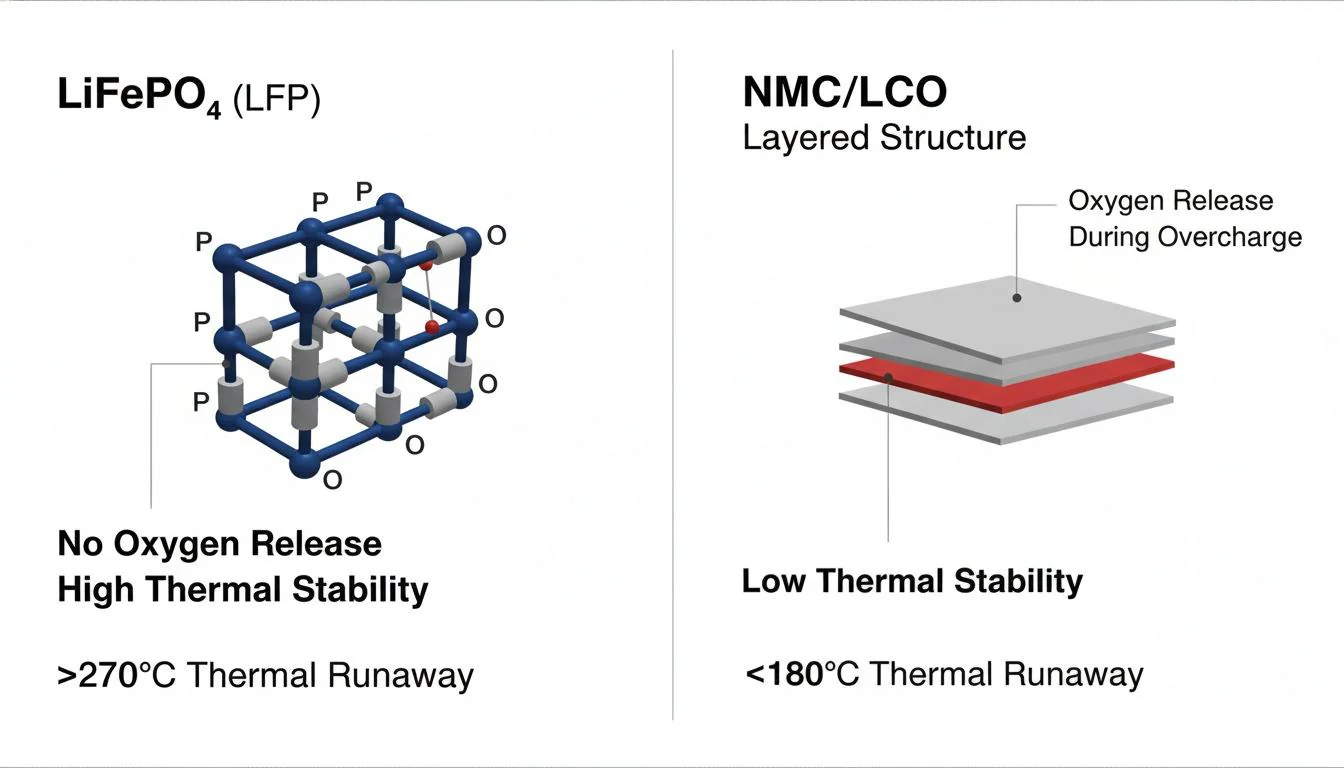

Most battery fires in residential settings involve NMC chemistry. A 2021 Tsinghua University study measured oxygen release during thermal abuse testing. NMC811 cells started releasing oxygen at 178°C. LiFePO4 cells released none below 600°C.

That temperature gap explains most of what you need to know about chemistry selection for residential storage. The rest is details about why the gap exists, how it affects longevity, and what it means for your wallet. But the core argument is simple: batteries installed near sleeping families should not contain chemistries that release their own oxidizer during failure.

The phosphate structure holds oxygen atoms in PO4 tetrahedra with bonds that take over 500 kJ/mol to break. For reference, organic C-C bonds average around 350 kJ/mol. Silicon-oxygen bonds in quartz are similar to phosphorus-oxygen bonds, which is why quartz survives conditions that destroy most other materials. The phosphate cage does not open at temperatures batteries encounter during operation or abuse.

NMC is different. The layered oxide structure binds oxygen less tightly. When those cells overheat past 150-200°C, the cathode starts shedding oxygen into the cell interior. NREL published thermal runaway data in 2020 showing what happens next: peak temperatures of 700-900°C, heating rates exceeding 100°C per minute during the runaway phase.

Firefighters struggle with these incidents. Water cools the cell exterior but does not stop the internal reaction. CO2 displaces atmospheric oxygen, but the reaction does not need atmospheric oxygen. The oxidizer comes from the cathode itself. Standard suppression techniques assume the oxidizer comes from outside the burning object. When that assumption fails, so does suppression.

LiFePO4 cells can fail. They swell and vent gas. The electrolyte can decompose and briefly ignite. But without sustained oxygen release from the cathode, the self-accelerating combustion phase does not develop. The cell dies without taking the house with it. Sandia National Laboratories confirmed this behavioral difference across multiple commercial cell types in abuse testing published in 2017. The LiFePO4 cells vented and lost capacity. The NMC cells caught fire.

The discharge voltage curve confuses engineers who learned on other chemistries. LiFePO4 sits at 3.2V from 90% down to 10% state of charge, barely changing. Put a voltmeter on the pack and you cannot tell if it has four hours of runtime left or forty minutes. Voltage-based state-of-charge estimation does not work.

The flat curve comes from phase separation. During discharge, particles split into lithium-rich and lithium-poor regions. A boundary moves through each particle as lithium exits.

This causes real problems. Cheap BMS boards designed for lead-acid or NMC give erratic readings when paired with LiFePO4 packs. Some residential installations have failed warranty claims because the monitoring system reported cells as defective when they were actually fine. The BMS simply did not know how to interpret the flat voltage curve.

The flat curve comes from phase separation. During discharge, particles split into lithium-rich and lithium-poor regions. A boundary moves through each particle as lithium exits. Two phases of fixed composition coexisting at equilibrium produce constant chemical potential, which means constant voltage. This is thermodynamics, not a quirk that engineers can design around.

The same phase-separation mechanism affects longevity. In NMC, lithium concentration changes continuously throughout each particle during cycling. The concentration swings create mechanical stress that accumulates over thousands of cycles until particles start cracking. Cracked particles lose electrical contact or expose fresh surface to electrolyte, which triggers side reactions that consume lithium.

LiFePO4 particles handle cycling differently. The two-phase boundary moves through the particle, but material on either side of the boundary stays at fixed composition. The particle interior does not see the concentration swings that cause fatigue in solid-solution cathodes. Volume change between charged and discharged states is 6.8% for LiFePO4, versus 10-15% for NMC. That difference compounds over thousands of cycles.

Field data supports the longevity claims. A 2019 TU Munich study examined German residential LiFePO4 installations with 5+ years of operation. Capacity retention averaged 92% at 2,000 cycles. The degradation trajectory suggested these systems would reach 80% capacity around 4,000-5,000 cycles.

NMC systems in similar German residential applications degraded faster. The worst performers were installations that kept batteries topped off during long summer days, waiting for evening demand or grid outages that rarely came. Sitting at high state of charge for extended periods accelerates decomposition at NMC cathode surfaces. The Ni4+ oxidation state present when NMC is fully charged is aggressive toward organic carbonate electrolytes. Decomposition products accumulate as a resistive film. The film keeps growing.

LiFePO4 sidesteps this failure mode. The Fe2+/Fe3+ redox couple operates at lower voltage and is less reactive toward electrolyte. Calendar aging still occurs but proceeds more slowly. The TU Munich data suggested roughly 2:1 advantage for LiFePO4 in daily-cycling applications, closer to 3:1 in backup-focused installations where cells sit at high charge for months at a time.

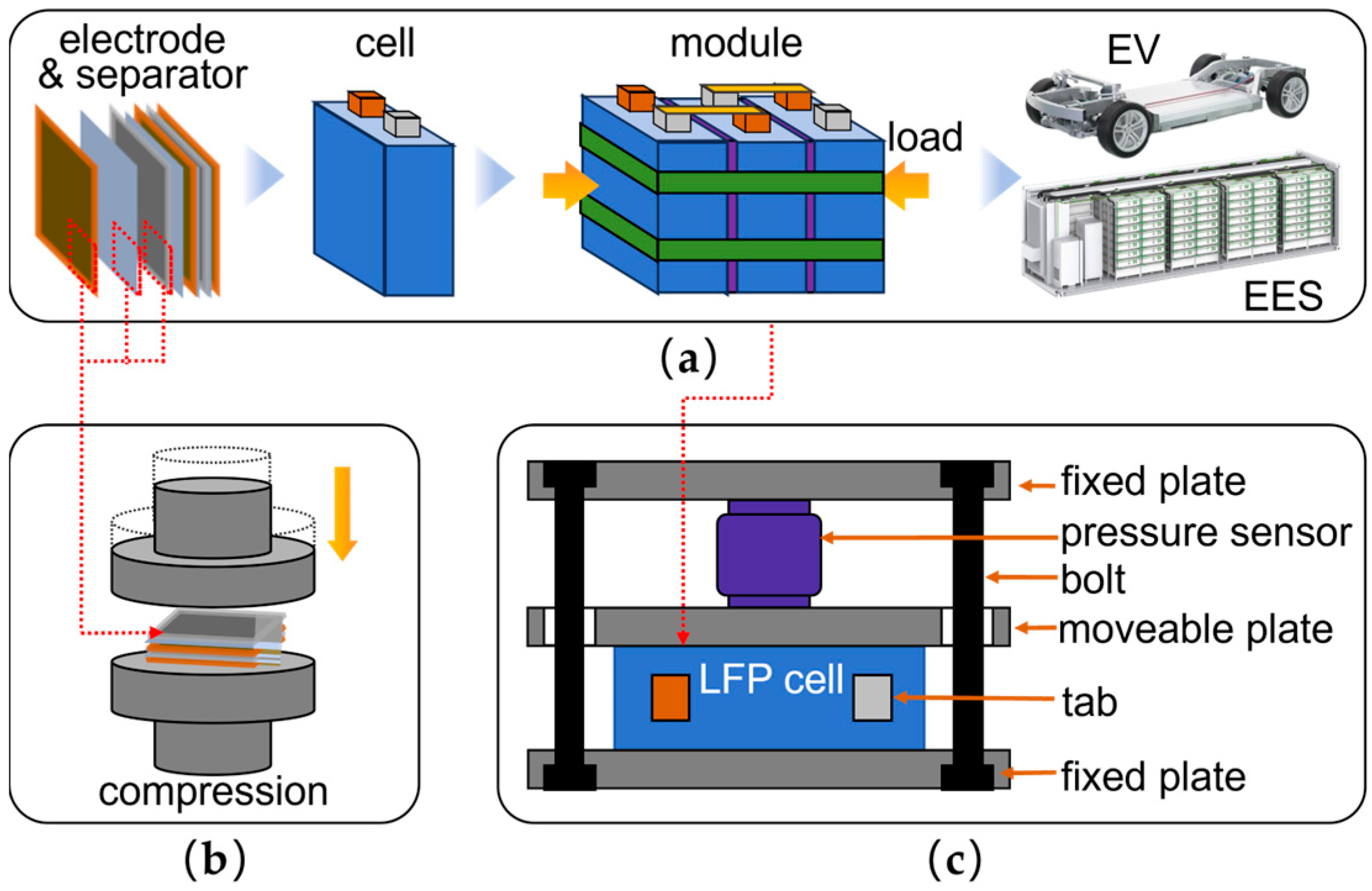

Manufacturing matters more than most buyers realize. Possibly more than chemistry selection itself, at least within the LiFePO4 category.

Raw LiFePO4 does not conduct electricity. Published conductivity values run around 10-9 S/cm, similar to window glass. A cathode made of insulating powder would be useless. Carbon coating fixes this by providing electronic pathways across particle surfaces, but the coating has to be right.

Good coatings are 2-5 nanometers thick, uniform across the particle surface, and consist primarily of graphitic carbon. Graphitic carbon conducts well because electrons can delocalize across the sp2-bonded structure. Bad coatings are thick, patchy, and contain amorphous carbon that conducts poorly. The conductivity difference between graphitic and amorphous coatings spans orders of magnitude.

Getting graphitic coatings requires precise process control. Temperature must stay within a narrow window. Carbon precursors like sugars or citric acid must decompose at temperatures that favor graphitization rather than charring. Atmosphere composition matters. Heating and cooling rates matter. Precursor distribution across the particle batch matters.

Manufacturers with ten years of continuous production have mapped these constraints through accumulated experience. They know which incoming precursor batches will cause problems. They have quality control methods that catch coating defects before cells ship. Newer operations lack this institutional knowledge. They have the same published literature, often the same equipment, but not the pattern recognition that comes from seeing thousands of batches succeed or fail.

Industry veterans suggest looking at production history when selecting suppliers. Five to seven years of continuous LiFePO4 manufacturing suggests a mature operation. Two years suggests a learning curve still in progress. The customers pay for learning curves through inconsistent quality and early failures.

Two cells with identical datasheet specifications from different manufacturers can perform very differently in practice. Rate capability, temperature tolerance, and aging behavior all depend on coating quality that specifications do not capture. This frustrates buyers who want to compare products on paper. It is also just how things work.

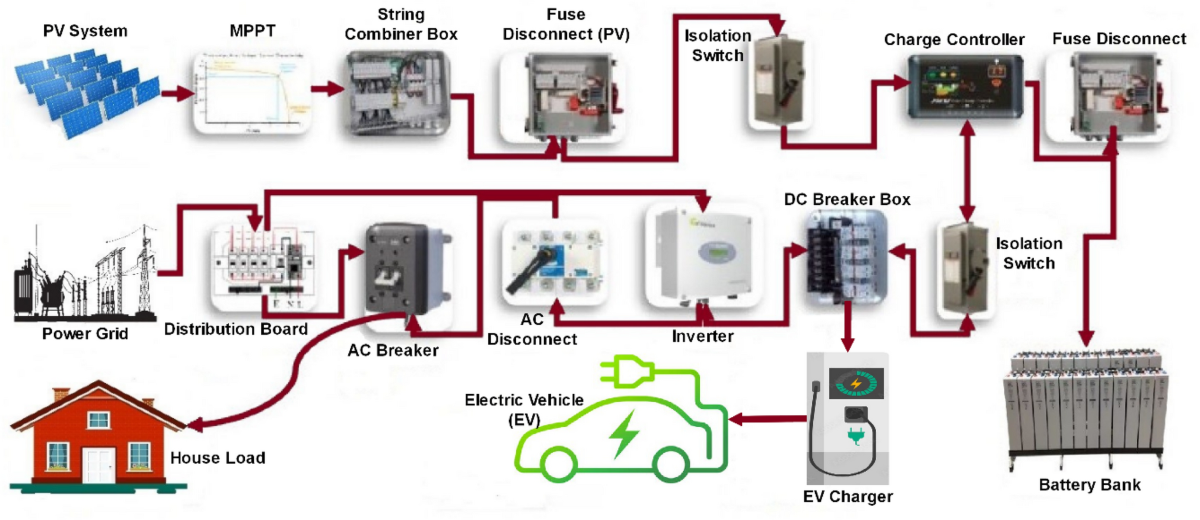

Upfront cost comparisons favor lead-acid and sometimes NMC. Lifecycle cost comparisons favor LiFePO4 in daily-cycling applications. The crossover point arrives around year 5-7, depending on specific usage patterns and local electricity rates.

Lead-acid illustrates why upfront cost comparisons mislead. Purchase price for equivalent capacity runs maybe 40% of LiFePO4 pricing. Cycle life at 50% depth of discharge is 400-500 cycles. Daily cycling burns through the battery in about 18 months. Over a 15-year analysis period, that means ten or more replacements.

The efficiency losses compound the replacement costs. Round-trip efficiency for lead-acid runs 75-85%, versus 92-96% for LiFePO4. Every kWh stored loses 15-25 cents to waste heat in the lead-acid system, versus 4-8 cents in LiFePO4. At 10 kWh daily cycling and $0.15/kWh electricity, the efficiency difference alone costs $2,500-4,000 over 15 years. Add the replacement battery costs and installation labor for ten swaps, and lead-acid becomes the most expensive option despite the lowest purchase price.

The math changes for backup-only applications. A system that cycles 50 times per year takes 10 years to reach 500 cycles. Calendar aging dominates over cycle aging in this scenario. LiFePO4 still lasts longer but the premium is harder to justify purely on economics. Some buyers in this situation choose lead-acid despite the maintenance requirements and lower efficiency, reasoning that they may never actually need the backup capacity and prefer to minimize capital at risk.

Cold weather affects LiFePO4 more than marketing materials suggest. The issue is not discharge performance, which holds up reasonably well down to -20°C. The issue is charging.

Below 0°C, lithium ions cannot intercalate into the graphite anode fast enough to keep up with charge current. The excess lithium deposits on the anode surface as metallic lithium rather than inserting into the graphite structure. This lithium plating damages capacity permanently. Worse, plated lithium can form dendrites that eventually cause internal shorts.

Quality BMS implementations block charging below safe temperatures, typically 0°C or slightly above. Premium systems include heating elements that warm the pack before accepting charge. The heating adds cost and consumes energy, but it prevents damage that would otherwise shorten service life.

Installations in unheated garages in cold climates need explicit attention to this issue. A system that works fine during summer may refuse to charge on winter mornings, or may charge slowly while the heating elements bring cells into range. This is not a defect. It is the chemistry working as designed to prevent damage.

What often gets overlooked in chemistry discussions: BMS quality varies dramatically across products using similar or identical cells. Two battery packs can use the same cells from the same manufacturer and deliver completely different reliability based on the battery management board.

Protection circuitry design differs. Cell balancing algorithms differ. Thermal monitoring implementation differs. State-of-charge estimation accuracy differs. These variations do not appear on datasheets. They show up years later when some products fail prematurely and others keep running.

The battery sits in an occupied home for 15-20 years. Families sleep meters from the installation. Smoke detectors provide the primary warning system.

Cheap BMS implementations have caused fires even in LiFePO4 systems. The fires spread more slowly than NMC fires because the chemistry does not sustain oxygen-fed combustion. But they still happen when protection circuits fail to trip, when cell imbalances go undetected and stressed cells overheat, when thermal monitoring misses hot spots developing in the pack.

Evaluating BMS quality before purchase is difficult. Production history helps. Warranty terms and claims rates help if you can find them. Teardown reviews from independent sources help. But there is no specification that captures "this BMS was designed by people who understand failure modes."

What definitely matters regardless of BMS: the battery sits in an occupied home for 15-20 years. Families sleep meters from the installation. Smoke detectors provide the primary warning system. There is no fire suppression system on standby, no thermal camera watching for hot spots, no technician monitoring for anomalies. The failure mode of the chemistry determines whether malfunction becomes a warranty claim, an insurance claim, or something worse.

NMC continues improving. Newer formulations show better thermal stability. The safety gap may narrow.

It has not narrowed yet. Reports of residential storage fires still predominantly involve NMC. The fundamental challenge remains: layered oxide cathodes contain weakly bound oxygen.

Sodium-ion has reached early commercialization but currently trails LiFePO4 on energy density and cycle life without consistently lower pricing.

Solid-state remains developmental. Optimistic projections continue placing commercial availability 3-5 years away, as they have since roughly 2015.

For purchasing decisions made now, LiFePO4 is the most validated chemistry for residential storage.