48V.

Most articles on this topic refuse to give a straight answer. They present pros and cons, offer balanced perspectives, and conclude that both options suit different needs. This approach generates clicks and avoids controversy but leaves readers no better informed than before they started reading. The framing suggests rough equivalence where none exists.

36V systems cost less. That advantage is real and worth acknowledging. A buyer on a strict budget who cannot afford the 48V option should buy the 36V option rather than no ebike at all. Transportation beats no transportation.

But cost is where the 36V advantages end. Every technical comparison efficiency, battery longevity, thermal margin, hill climbing capability, cold weather performance favors 48V. The gaps are large. They compound over time. And they trace back to a single equation that electrical engineers have understood for over a century.

Current Squared

Power loss equals current squared times resistance — the fundamental equation governing efficiency in electrical systems

P = I²R determines how much energy gets wasted as heat in any electrical system. The squared term matters more than people realize.

At 750W output through a system with 65 milliohms total resistance, a 36V configuration draws 20.8 amps. Square that, multiply by resistance, and the system wastes 28.1 watts. The 48V configuration draws 15.6 amps for identical output and wastes 15.8 watts. The 36V setup throws away 78% more energy doing nothing useful.

Power Loss Comparison at 750W Output

The 65 milliohm figure needs context. That number represents every resistive element between battery terminals and motor windings summed together. Battery internal resistance contributes 15-30 milliohms depending on cell quality, state of charge, and temperature. Wiring adds 8-15 milliohms depending on gauge and run length. Connectors add 2-5 milliohms per junction. Controller FET on-resistance adds 3-12 milliohms depending on how many MOSFETs are paralleled and what grade of silicon the manufacturer chose. Motor phase wires and winding resistance add the rest.

Cheap systems can hit 90-100 milliohms. Premium builds with quality cells, heavy gauge wire, and controllers running six or eight FETs in parallel can get down to 40-50 milliohms. But component quality cannot close the gap that voltage selection creates. A premium 36V build still wastes more energy than a mediocre 48V build at equivalent power output, because the current difference dominates.

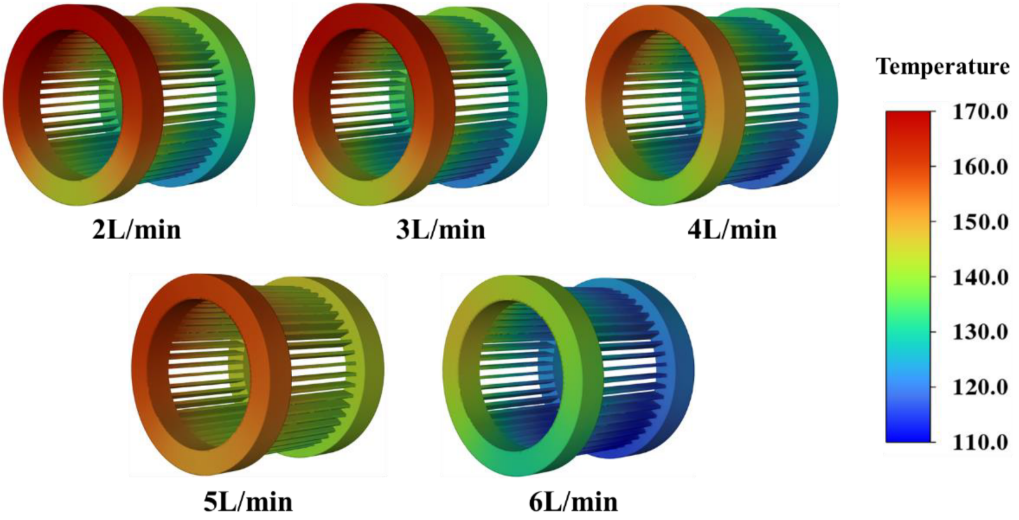

Those percentages stay constant across the power range, but the absolute numbers balloon during high-demand riding. A hard climb at 1200W sustained for several minutes means the 36V system is dumping an extra 30+ watts into heating components continuously. That heat soaks into controller FETs, motor windings, battery cells. Everything runs hotter. Everything degrades faster.

Multiply across thousands of hours of riding. A commuter doing 45 minutes each way, five days a week, accumulates 390 hours of ride time per year. If average power consumption is 350W and the efficiency gap between platforms is 12 watts average, the 36V rider wastes 4.68 kWh per year to excess heating. The electricity cost is negligible. The thermal stress on components is not.

The relationship follows Arrhenius curves that show dramatic lifespan reduction for every 10°C increase in operating temperature. The extra heat from 36V operation accumulates into earlier failures, reduced performance, and shorter useful life for every component in the power path.

The consequences play out over months and years of ownership in ways that casual buyers never connect to voltage selection.

Cells Die Faster at Higher Current

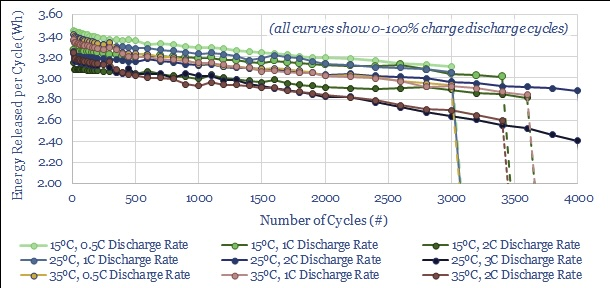

Samsung, LG, Panasonic, and Molicel all publish cycle life data for their cells. The curves show remaining capacity versus cycle count at various discharge rates. The pattern is consistent across chemistries and manufacturers: cells discharged harder die younger. The relationship is nonlinear. Bumping average discharge from 0.7C to 1.2C might cost 30% of total cycle life. Bumping from 1.2C to 1.8C might cost another 40%.

The degradation mechanisms are well understood. High current accelerates lithium plating on the anode surface, permanently consuming cyclable lithium. High current drives faster growth of the solid-electrolyte interphase layer, increasing internal resistance and reducing capacity. High current generates more heat inside the cell, which accelerates electrolyte decomposition and promotes copper dissolution from the negative current collector. These mechanisms interact. Damage from one accelerates the others.

A 36V pack delivering a given wattage to the motor runs each cell about 33% harder than a 48V pack delivering identical wattage. This percentage lands on the steep part of the degradation curves where small changes in discharge rate produce large changes in cycle life.

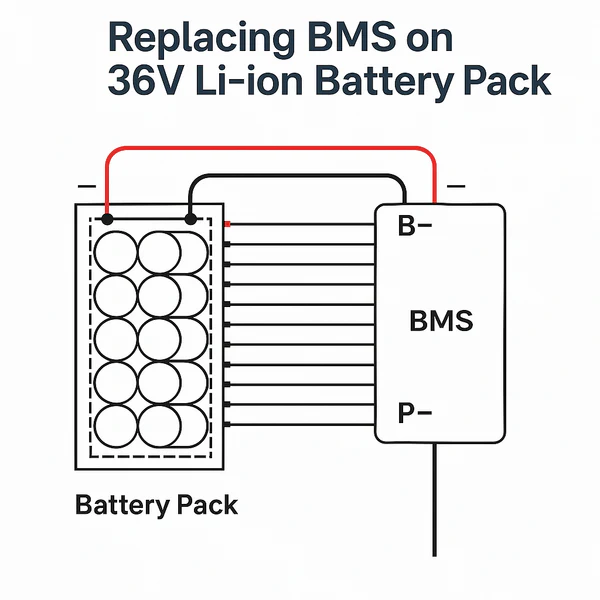

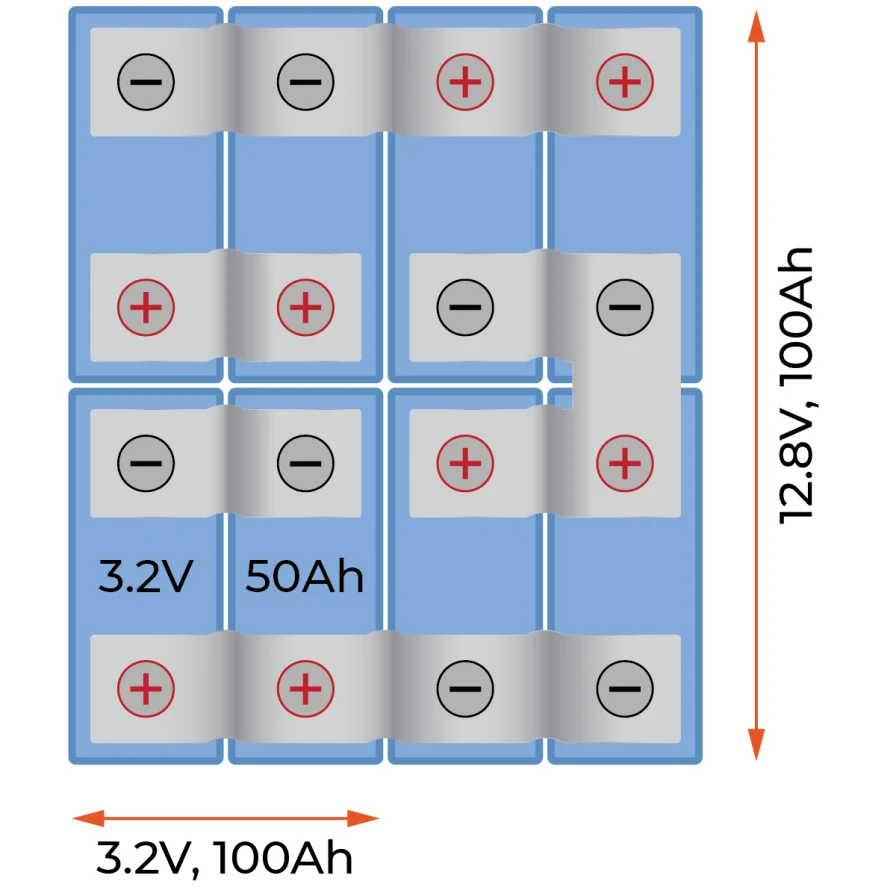

The difference between 10S and 13S configurations deserves attention. A 36V pack uses ten cells in series. A 48V pack uses thirteen. The 48V pack has 30% more cells sharing the load, which means 23% less current per cell for equivalent pack current. Combined with the voltage ratio, the result is that each cell in a 48V pack experiences roughly 33% lower discharge current than each cell in a 36V pack delivering identical motor power.

The 30Q datasheet shows approximately 500 cycles to 80% capacity at 2C discharge, roughly 800 cycles at 1C, and over 1000 cycles at 0.5C. Moving from 1.5C average to 1.0C average—roughly what the 36V-to-48V transition accomplishes for typical riding patterns—can extend cycle life by 40-60%.

Endless-sphere threads going back to 2014 and 2015 show the pattern playing out in the field. Riders comparing notes find that 36V packs fade noticeably around month 14-18 while equivalent 48V packs hold capacity past month 24-30. The reports align with what the manufacturer curves predict. Nobody runs controlled experiments, but thousands of data points pointing the same direction carry weight.

The specific cell model matters less than the pattern. The 25R that dominated ebike builds from 2015 to 2019 shows the same degradation shape as the 30Q that replaced it. The 50E, designed for high capacity rather than high current, degrades even faster under load because its chemistry trades power capability for energy density. The Molicel P42A tolerates abuse better than most but still follows the same curve shape. No cell chemistry escapes the physics.

Cold weather amplifies the effect. Cell internal resistance spikes below 10°C. At room temperature a healthy cell might measure 20-25 milliohms. At freezing that same cell might measure 60-80 milliohms. A 36V system's higher current multiplies through that elevated resistance, producing worse voltage sag and accelerating degradation from the combination of thermal stress and current stress. Winter range on 36V drops 40-50% from summer baseline. The same rider on 48V loses 25-35%. Both blame the weather. One system handles the weather measurably better.

The degradation remains invisible for the first year. New cells have margin built in. A pack rated for 15Ah delivers 15Ah even when the cells are being stressed beyond their optimal operating point. The owner rides without noticing problems. Sometime around month 14 to 18, depending on usage intensity, the range starts dropping. The pack that once delivered 45km now struggles to reach 35km. The owner blames tire pressure, wind, imagination, winter. Spring arrives and the range does not recover. By then the damage is permanent.

The 48V owner running equivalent cells at equivalent energy throughput reaches the same degradation point later—month 24 to 30 depending on usage. The extra 8-12 months of useful life represents real value. Pack replacement costs somewhere between $200 and $500 depending on capacity and cell quality. Getting an extra year of service before that expense arrives changes the ownership economics.

Delivery riders and commercial users see this pattern accelerated. A food delivery rider covering 80-100km daily puts more stress on a pack in six months than a recreational rider puts on a pack in three years. The degradation curves compress proportionally. A 36V pack supporting commercial delivery might fade noticeably by month 6-8 and require replacement by month 12. The same rider on 48V gets usable service through month 12-15 with replacement around month 18-20. The absolute months change but the ratio between platforms stays roughly constant.

What Runs Hot

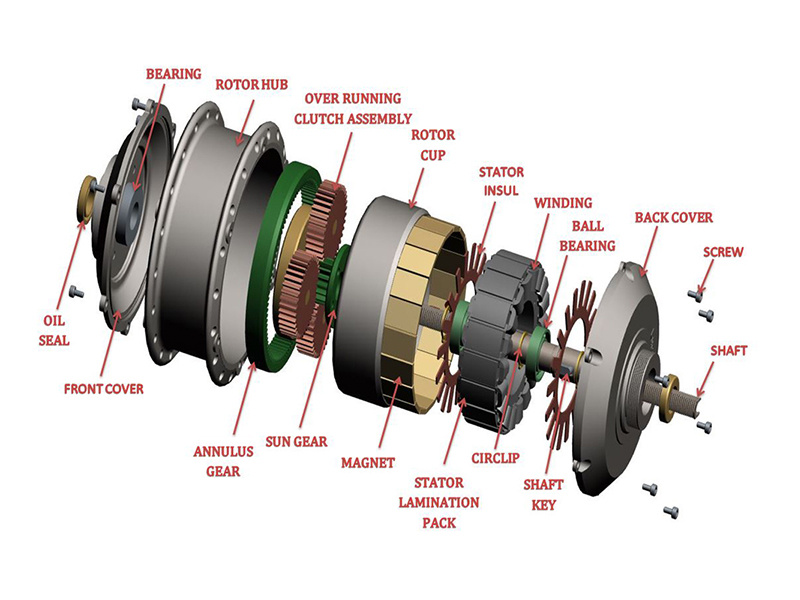

Controllers and motors both suffer from the current differential, though in different ways.

Budget controllers ship with four FETs, a small heatsink, and current ratings that assume brief bursts. The 36V system runs higher current through those FETs for equivalent mechanical output. Conduction losses scale with current squared. Temperature differential between 36V and 48V operation might be 25-35°C depending on thermal design. Junction temperatures creep toward limits during sustained climbs on warm days. Failure happens gradually rather than suddenly—occasional dropouts, weird behavior under load, a lag between throttle input and motor response—until something finally gives. Controllers from Grin or ASI cost more because they include enough silicon and thermal mass to handle sustained current without stress.

The cheap controllers that come with Amazon ebikes are designed to pass a brief factory test and survive the warranty period. The FETs handle the rated peak current with minimal margin. The heatsink manages cruising loads adequately. Push the system harder than the designers expected and thermal limits arrive faster than the buyer expected.

Motor windings have a related problem. Copper resistance rises about 0.4% per degree Celsius. A winding running at 120°C instead of 80°C has 16% higher resistance, which generates more heat at a given current, which pushes temperature higher. Equilibrium temperature depends on cooling capacity and current flow. The 36V system settles at a higher equilibrium for equivalent mechanical output.

The motor works fine until suddenly it does not.

Hot motors also demagnetize. Neodymium magnets lose field strength at elevated temperature. A motor running summer after summer at 90°C internal temperature gradually weakens. The torque constant drops. Riders who notice attribute the weakness to battery aging without realizing the magnets are the actual problem. Forum threads describe riders who rebuilt hub motors multiple times for burned windings before realizing the magnets had degraded past the point where new windings could restore original performance.

Back-EMF creates a separate limitation. Motors generate voltage proportional to rotational speed. This voltage subtracts from supply voltage, reducing what remains to push current. When back-EMF approaches supply voltage, current chokes regardless of throttle. The ceiling scales with voltage: a motor topping out at 25 km/h on 36V tops out around 33 km/h on 48V. Hill climbing exposes this. Maintaining speed on a grade requires torque while spinning. The 36V system runs out of voltage headroom before the 48V system does. Hub motors suffer more because they spin at wheel speed while mid-drives benefit from gear reduction. The Bafang G310 and G060 struggle on 36V once grades exceed 5-6%. On 48V the same motors handle 10% grades.

Anyone who has ridden both voltage platforms on identical hardware up a real hill understands the difference within seconds. The 48V bike pulls. The 36V bike struggles. No amount of throttle input changes the underlying physics.

The Market Reality

48V packs weigh roughly 280-320 grams more than equivalent 36V packs due to three extra cells plus BMS overhead. On a system weighing 95+ kg with rider, that represents 0.3% of moving mass. Nobody perceives that difference through handling feel. The weight argument exists because it gives 36V advocates something concrete to cite. Folding bike owners who carry their bikes up stairs daily might legitimately care about 300 grams. Everyone else is rationalizing.

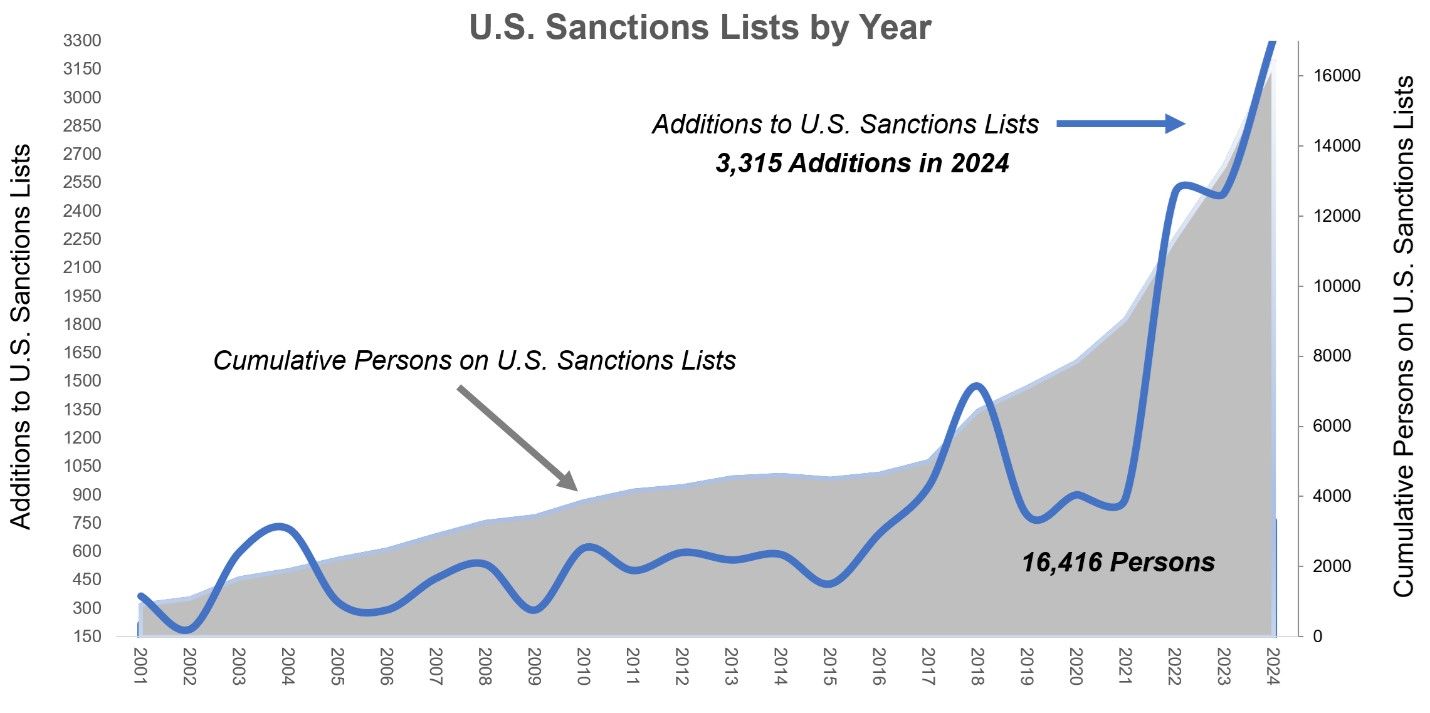

36V persists because 36V tooling is amortized, 36V BMS ICs are commodity parts, and 36V components move through established distribution channels at lower cost. Building a 36V system costs less. That price difference appears on the listing where buyers can see it.

The performance difference appears months later, on the first serious hill, during the first winter. By then the sale is complete.

Amazon is full of 36V ebikes because Amazon buyers optimize for price and Amazon sellers optimize for margin. The listings do not explain that the cheap option runs hotter, degrades faster, and struggles on hills. That information would reduce conversion rates. Buyers see two similar-looking bikes at different prices and choose the cheaper one without understanding what they are giving up.

The informed segment of the market figured this out years ago. Endless-sphere conversations from 2015 and 2016 already show experienced builders steering newcomers toward 48V. Grin Technologies designs for 48V and above. Bafang's BBSHD was designed around 48V from launch; the Ultra requires 48V minimum. Third-party controller developers like the people behind Phaserunner and Baserunner optimize for 48V. TSDZ2 aftermarket firmware assumes 48V. Serious builders converged on 48V long before the casual market noticed there was a question to ask.

The price premium for 48V has compressed over the past five years as 48V became the volume platform for anything beyond bottom-tier builds. What used to be a 25-30% price gap is now closer to 12-18%. Component costs dropped as volumes rose. The gap continues narrowing while the physics-driven performance gap stays constant.

Someone who plans to keep a bike more than two years, rides hills, rides in winter, or hauls cargo should not look at 36V. The upfront savings do not compensate for accelerated degradation and reduced capability.

Someone who needs minimum cost for gentle flat-ground commuting and treats the bike as disposable can make 36V work. The disadvantages matter less when usage stays light and ownership stays short. But that scenario describes a narrower slice of buyers than the 36V market share would suggest. Most people who buy cheap 36V bikes end up wanting to ride further, climb hills, or keep the bike longer than they originally planned. The limitations become apparent eventually.

The question asked which platform is better. Across essentially any use case involving real performance demands or ownership beyond a couple years, 48V wins by margins that make the comparison straightforward.

The Verdict

For any rider prioritizing efficiency, longevity, hill climbing capability, or cold weather performance, 48V is the clear choice. The physics are unambiguous, and the real-world data confirms it.