Marcus Chen

January 20, 2026

What is Smart Energy Storage?

Smart energy storage is a battery system that decides when to charge and discharge based on data it collects about itself and the electricity market. That definition fits on a napkin. The complexity is in what "decides" means when the thing doing the deciding is software that cannot explain its own reasoning.

Grid-scale battery energy storage facilities

Battery cells report voltage. From voltage, you infer charge. The inference is wrong.

Not slightly wrong. Not wrong in ways that average out. Wrong in ways that accumulate and hide and then reveal themselves at the worst possible moment, like when a grid operator calls for 50 megawatt-hours of discharge during a summer demand peak and discovers the battery has 43.

The problem starts with the solid electrolyte interphase. Every time a lithium iron phosphate cell charges, a thin film deposits on the graphite anode. The film is made of decomposition products from the electrolyte, primarily lithium carbonate and lithium fluoride formed when the ethylene carbonate and lithium hexafluorophosphate in the electrolyte react at the graphite surface. The reaction consumes lithium ions that would otherwise contribute to capacity. Once trapped in the SEI film, those lithium ions never return to circulation. The cell's datasheet says 280 ampere-hours. After 500 cycles, the cell holds 265. After 1,500 cycles, maybe 240. After 3,000 cycles, the number depends on how the cell was treated, which nobody tracked with sufficient granularity to know.

The voltage curve does not announce this loss. Lithium iron phosphate has an unusually flat voltage profile between 20% and 80% state of charge. The flatness that makes iron phosphate attractive for applications requiring stable voltage also makes it terrible for inferring state of charge. A cell at 30% charge and a cell at 60% charge may differ by only 30 millivolts under load. Measurement noise and temperature variation can exceed that difference. The only way to find the missing capacity is to discharge fully and measure what comes out, which nobody does in operational systems because it takes hours and wears the cell further.

State-of-health estimation algorithms try to infer degradation from indirect signals. The good ones analyze the shape of the constant-current charging phase, looking for subtle changes in slope that correlate with capacity loss observed in laboratory teardowns. A slight increase in the time spent in the constant-voltage tail phase. A shift in the inflection point where current begins tapering. An uptick in the temperature differential between the cell surface and the ambient air during fast charging. These signals exist in the data. Extracting them requires models trained on thousands of cells cycled to failure under varied conditions.

The training data problem is underappreciated. Most publicly available datasets come from laboratory cycling under controlled conditions: fixed temperatures, consistent charge rates, regular full cycles. Real operational data looks nothing like this. A grid storage system might cycle once daily for three months, then sit idle for a week during shoulder season, then cycle twice daily during a heat wave. The charge rates vary with market conditions. The temperature fluctuates with weather and HVAC system performance. A cell that spent its life in laboratory cycling will age differently from a cell that spent its life in operational chaos. Algorithms trained on the former will misjudge the latter.

The interaction effects make prediction harder still. SEI growth increases internal resistance. Higher resistance causes more heat during charging because more energy dissipates as waste. More heat accelerates SEI growth because the decomposition reactions have positive temperature coefficients. The feedback loop means degradation is not linear. A cell that lost 5% capacity in its first two years may lose 12% in its third year. The nonlinearity depends on operating history in ways that resist simple modeling.

Cathode degradation adds another layer of uncertainty. In lithium iron phosphate, iron ions can dissolve from the olivine structure and migrate through the electrolyte to the anode, where they catalyze additional SEI formation and consume more lithium. The dissolution rate depends on voltage, temperature, and the presence of trace water contamination in the electrolyte. Different manufacturing batches have different contamination levels. Predicting cathode degradation requires knowing things about cell provenance that purchasers rarely have access to.

Some companies claim their algorithms achieve state-of-health estimation within 2% accuracy. The claim is probably true for cells similar to those in the training set operated under similar conditions. The claim says nothing about cells from a different manufacturing batch, or cells operated in a desert climate when the training data came from temperate installations, or cells approaching end of life when the training data mostly covered mid-life operation. The edge cases are where the money is lost.

Smart storage systems need continuous self-monitoring that goes beyond what simple battery management provides. The monitoring must detect not just threshold violations but trend changes. A cell whose temperature rise during charging has increased 0.3 degrees per month for six months is telling you something, even if the absolute temperature remains within spec. A string whose voltage dispersion during charging has widened over the past year is flagging a weak cell that will eventually limit the entire string. Catching these signals requires storing and analyzing historical data at a granularity that most systems a decade ago did not support. The storage and analysis have gotten cheaper. Whether operators actually look at the outputs or leave them to accumulate in dashboards nobody checks until something fails is another matter.

◆ ◆ ◆

The intelligence layer of a smart storage system optimizes within constraints set by electrochemistry. Bad chemistry with good software loses to good chemistry with mediocre software. The software discussion dominates conference panels and venture capital pitches, but the chemistry discussion determines which projects make money.

Lithium iron phosphate won the stationary storage market through a combination of properties that nobody planned. The chemistry was originally considered inferior to nickel-rich alternatives because of its lower energy density. A kilogram of iron phosphate cells stores about 160 watt-hours. A kilogram of nickel-manganese-cobalt cells stores 250 or more. For electric vehicles, where mass affects range and efficiency, the difference matters enormously. For stationary storage, where the battery sits on land that costs $50,000 per acre, the difference barely registers in project economics.

Thermal stability mattered more than anyone expected. Iron phosphate begins thermal decomposition around 270 degrees Celsius. At that temperature, the olivine structure releases oxygen slowly and the reaction is relatively controllable. Nickel-manganese-cobalt begins exothermic decomposition around 150 degrees Celsius, and once it starts, the reaction accelerates as heat builds. An iron phosphate cell can survive abuse conditions that would send an NMC cell into thermal runaway. The gap translates directly into safety margins, insurance premiums, permitting timelines, and setback requirements from occupied structures.

Bad chemistry with good software loses to good chemistry with mediocre software.

A utility-scale NMC installation requires more firefighting infrastructure than iron phosphate. More distance from buildings where people work. More expensive containment vessels designed to handle gas venting during thermal events. More complex monitoring systems to catch early warning signs of cell failure. More stringent maintenance protocols. The costs accumulate in ways that spec sheet comparisons miss because spec sheets do not include insurance quotes and fire marshal negotiations.

The cycle life difference compounds these advantages. Iron phosphate cells routinely exceed 6,000 full cycles before reaching 80% of original capacity. Some manufacturers claim 10,000 cycles under controlled conditions. NMC cells typically reach 2,000 to 3,000 cycles depending on formulation and operating conditions. For a grid storage asset expected to cycle once or twice daily for fifteen years, the iron phosphate system may never need replacement. The NMC system will probably need one or two battery swaps during its project lifetime. Battery replacement costs include not just the cells but also labor, downtime, logistics, and disposal of the old cells. A project that budgeted for one chemistry swap may find the second swap pushes economics below acceptable returns.

Cobalt absence mattered too, though more for procurement departments than for engineering. NMC cathodes contain 10% to 20% cobalt by weight depending on formulation. The cobalt supply chain runs through the Democratic Republic of Congo, where artisanal mining operations have attracted scrutiny from human rights organizations, investigative journalists, and ESG-focused investors. Corporate sustainability reports must now address supply chain labor practices. Procurement officers must demonstrate due diligence. Iron phosphate contains no cobalt. The due diligence burden disappears. The sustainability report becomes simpler. The investor questions become easier to answer.

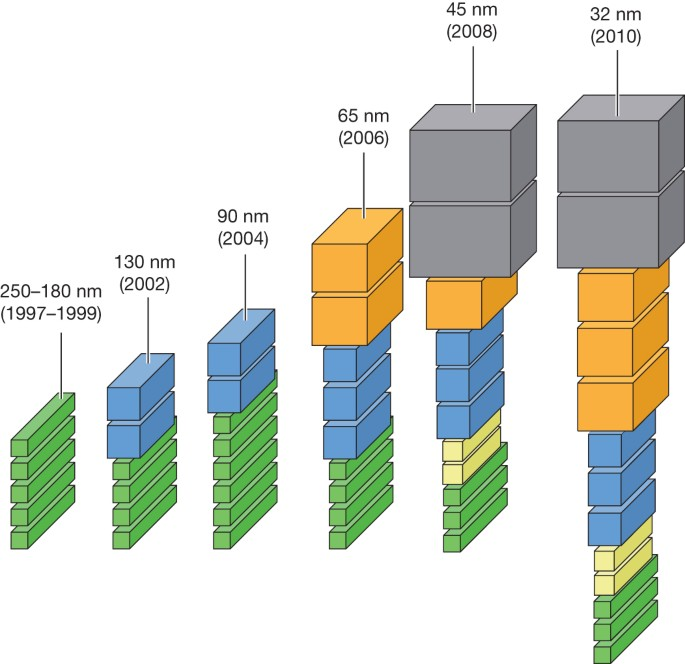

Chinese manufacturers, who now dominate iron phosphate production, initially pursued the chemistry because they lacked access to the patents covering NMC formulations. Western battery companies had locked up NMC intellectual property. Chinese companies, constrained to chemistries they could legally manufacture, invested heavily in iron phosphate process optimization. The constraint that seemed like a disadvantage turned into dominance when the market discovered it preferred iron phosphate anyway.

CATL and BYD did not win because they had better algorithms. They did not win because their management systems detected degradation more accurately or their energy management systems optimized market participation more cleverly. They won because they scaled the right chemistry while Western competitors chased energy density metrics that stationary storage did not need. By the time the market preference became clear, the Chinese manufacturers had accumulated years of process learning and built production capacity that competitors could not quickly match.

battery manufacturing requires precision at scale that took Chinese companies over a decade to master

This section will be short because the market participation problem receives more attention than it deserves relative to its actual contribution to project value.

Yes, reinforcement learning can improve bidding strategies. Yes, the improvement can reach 50% compared to simple rule-based approaches in volatile markets like Texas ERCOT. Yes, the algorithms discover patterns that human traders miss. The documentation for these claims is solid.

How much does that improvement matter in overall project economics? A 100 megawatt-hour storage system operating in ERCOT might generate $3 million per year in gross revenue under average bidding and $4.5 million under optimized bidding. The $1.5 million improvement looks large until you compare it to the $30 million capital cost of the system. The algorithmic optimization moves the project from an 8-year payback to a 6-year payback. Worthwhile, but not transformative.

The improvement is also temporary. As more participants adopt similar bidding approaches, the edges get arbitraged away. The patterns that generated alpha in 2022 get incorporated into everyone's models by 2025. The market equilibrates toward efficiency. First movers capture a temporary advantage. Late movers find smaller gains.

The companies selling bidding optimization software have strong incentives to emphasize the revenue improvement. They are selling software. The companies building and operating storage projects have more qualified views. The project economics depend far more on capital costs, which depend on battery prices, which depend on chemistry and manufacturing scale, which depend on decisions made by CATL and BYD. The software layer optimizes at the margin. The commodity layer determines the base.

◆ ◆ ◆

The hype around sodium-ion batteries deserves more pushback than it receives.

On paper, the case for sodium-ion looks strong. Sodium is abundant and cheap. Seawater contains effectively unlimited supply. The geopolitical concentration that makes lithium a strategic concern does not apply to sodium. If sodium-ion cells can match lithium iron phosphate on performance metrics, the supply chain advantages make them obviously preferable.

The conditional in that sentence is doing a lot of work.

CATL announced its Naxtra sodium-ion cells with specifications that look impressive: 175 watt-hours per kilogram energy density, 10,000 cycle life, operation down to negative 40 degrees Celsius. The numbers match or exceed iron phosphate. If accurate and reproducible at scale, sodium-ion would be a genuine breakthrough.

The "if" matters because announced specifications from a single manufacturer do not constitute proven technology. CATL has strong incentives to present optimistic numbers. The company is publicly traded and competes for investor attention with narratives about technology leadership. Product announcements that generate headlines serve corporate interests regardless of whether the products perform as described in mass production.

The cycle life claims in particular need scrutiny. A 10,000 cycle claim means the cell retains 80% of initial capacity after 10,000 full charge-discharge cycles. Verifying that claim through actual cycling takes years. Accelerated testing methods exist, but they make assumptions about how degradation scales with stress that may not hold for new chemistries. A sodium-ion cell cycled at elevated temperature to speed up testing may degrade through mechanisms that differ from room-temperature cycling. The correlation between accelerated test results and real-world performance has to be established empirically, and empirical establishment takes time.

The cold-weather performance claims also need field validation. Sodium-ion has theoretical advantages at low temperatures because sodium ions diffuse more easily through electrolyte than lithium ions at the same temperature. The theoretical advantage needs confirmation in actual installations facing actual winters, with actual thermal management systems and actual pack-level heat distribution. Laboratory climate chambers do not replicate the complexity of outdoor deployment.

Large-scale manufacturing begins in 2026, according to company announcements. Whether the cells coming off production lines match the prototype specifications will not be known until installations operate for two or three years under varied conditions. That puts meaningful validation around 2028 or 2029, possibly later if early deployments are conservative pilot projects rather than aggressive commercial rollouts. Investors and project developers making bets today on sodium-ion are extrapolating from limited data and announcements with promotional intent.

The renewable energy transition depends on storage technologies that remain unproven at scale

The supply chain advantage is real but narrower than presentations suggest. Sodium-ion cells still require other materials with their own supply constraints. The anode is typically hard carbon rather than graphite. Hard carbon production is less mature than graphite production, and scaling it introduces new bottlenecks. The electrolyte solvents and salts differ from lithium-ion but still require chemical manufacturing capacity. The current collectors use aluminum on both sides rather than copper and aluminum, which simplifies one aspect but changes nothing about aluminum availability. The separator membranes are similar to lithium-ion and face similar supply constraints.

The shift from lithium to sodium addresses the lithium bottleneck specifically. It does not eliminate all material constraints, just the most publicized one. Whether that shift is worth the uncertainty of an immature technology depends on how much you worry about lithium supply versus how much you worry about technology risk. Reasonable people can disagree about the tradeoff.

Timeline skepticism matters more than viability skepticism. Sodium-ion probably works. Whether it works well enough soon enough to capture major market share before iron phosphate costs decline further and entrench that chemistry's dominance is uncertain. Learning curves favor incumbents. Iron phosphate manufacturers are not standing still while sodium-ion scales up. The target is moving.

Sodium-ion may prove out exactly as advertised and capture major market share by 2030. Certainty at this stage is unwarranted. The breathless coverage treating sodium-ion as a solved problem obscures genuine uncertainty. Anyone making 20-year infrastructure investments based on sodium-ion reaching price parity by 2027 is making a bet, not executing a plan.

Solid-state batteries have been five years from commercialization for twenty years.

The physics is attractive. Replace the liquid electrolyte with a solid material and several problems disappear. Liquid electrolytes are flammable, contributing to thermal runaway risk. Solid electrolytes are not. Liquid electrolytes limit the use of lithium metal anodes because lithium dendrites grow through the liquid and short the cell. Solid electrolytes, in principle, can block dendrite propagation and enable lithium metal anodes with much higher theoretical capacity than graphite.

The engineering is brutal. Solid-solid interfaces behave differently than solid-liquid interfaces. When a lithium ion moves from a solid electrolyte into a solid electrode, it must cross a boundary between two crystalline structures that do not perfectly match. The mismatch creates resistance. Worse, the electrode materials expand and contract as lithium moves in and out, but the solid electrolyte does not accommodate this expansion the way a liquid would. The mechanical stress causes cracking and delamination at the interface. Cycle life suffers.

The solutions proposed for these problems require either very high stack pressure to maintain contact, which complicates cell design and adds weight, or exotic interlayer materials that are difficult to manufacture at scale, or entirely new electrode formulations that introduce their own uncertainties.

Toyota has been promising solid-state batteries for vehicles since 2017. The timeline keeps slipping. QuantumScape went public in 2020 with a valuation implying imminent commercialization. The company has since delivered sample cells to partners but has not announced mass production dates. Samsung SDI, CATL, and others have made similar announcements with similar ambiguity about timelines.

The pattern suggests that the fundamental obstacles are harder than optimistic projections assumed. Manufacturing process development takes longer than laboratory proof-of-concept. Scaling from hand-assembled prototype cells to automated production lines exposes problems that did not appear at small volumes. Cost reduction to competitive levels requires learning curves that have not yet begun.

Solid-state batteries will probably work eventually. Whether "eventually" means 2028 or 2035 or later remains unclear. Betting on solid-state for near-term projects is not prudent. Betting against solid-state ever working is also not prudent. Uncertainty is the only defensible stance, which the promotional material around the technology does not encourage.

◆ ◆ ◆

Market participation optimization is where smart storage systems earn their premium over dumb storage systems. The premium is real. The mechanism is less magical than the marketing implies.

A storage system participating in wholesale electricity markets faces a sequential decision problem. Every five minutes, it can choose to charge, discharge, or idle, at various rates. Each choice affects the state of charge available for future choices. The revenue depends on prices that fluctuate unpredictably. The optimization seeks the sequence of decisions that maximizes expected revenue over some horizon.

The traditional approach uses mixed-integer linear programming or dynamic programming with a price forecast as input. The forecast comes from statistical models or commercial services. The optimization takes the forecast as given and computes the best response. Performance depends heavily on forecast accuracy, and forecasts are often wrong by amounts that matter.

Reinforcement learning takes a different approach. Instead of optimizing against a point forecast, the algorithm learns a policy that maps states (current state of charge, recent prices, time of day, weather conditions) to actions. The policy is learned by repeatedly simulating market interaction and adjusting weights to increase cumulative reward. The result is a mapping that implicitly incorporates forecast uncertainty because the training process exposed the algorithm to many possible price sequences.

The revenue improvement from reinforcement learning compared to traditional optimization is documented at 50% or more in some markets. The improvement is real. It comes from better handling of uncertainty, faster adaptation to changing market conditions, and discovery of patterns in price data that human analysts did not explicitly program.

The improvement is also context-dependent. Markets with high volatility and complex dynamics offer more room for algorithmic outperformance. Markets with flatter price profiles and simpler structure offer less. As more participants adopt similar algorithms, the edges that early adopters captured get arbitraged away. The 50% improvement measured in 2022 may become 20% by 2027 as the techniques commoditize.

A more basic limitation: the algorithms optimize what they are told to optimize. They maximize revenue, or some weighted combination of revenue and state of health preservation, according to objective functions that engineers specify. They do not reason about whether the objective function is correct. They do not anticipate regulatory changes, contract renegotiations, or counterparty bankruptcies. The decisions that determine project success or failure are still made by humans.

Software optimization creates value at the margin, but cannot overcome fundamental hardware economics

The conversation about smart energy storage that matters most is the one about where batteries come from, and that conversation is uncomfortable for audiences outside China.

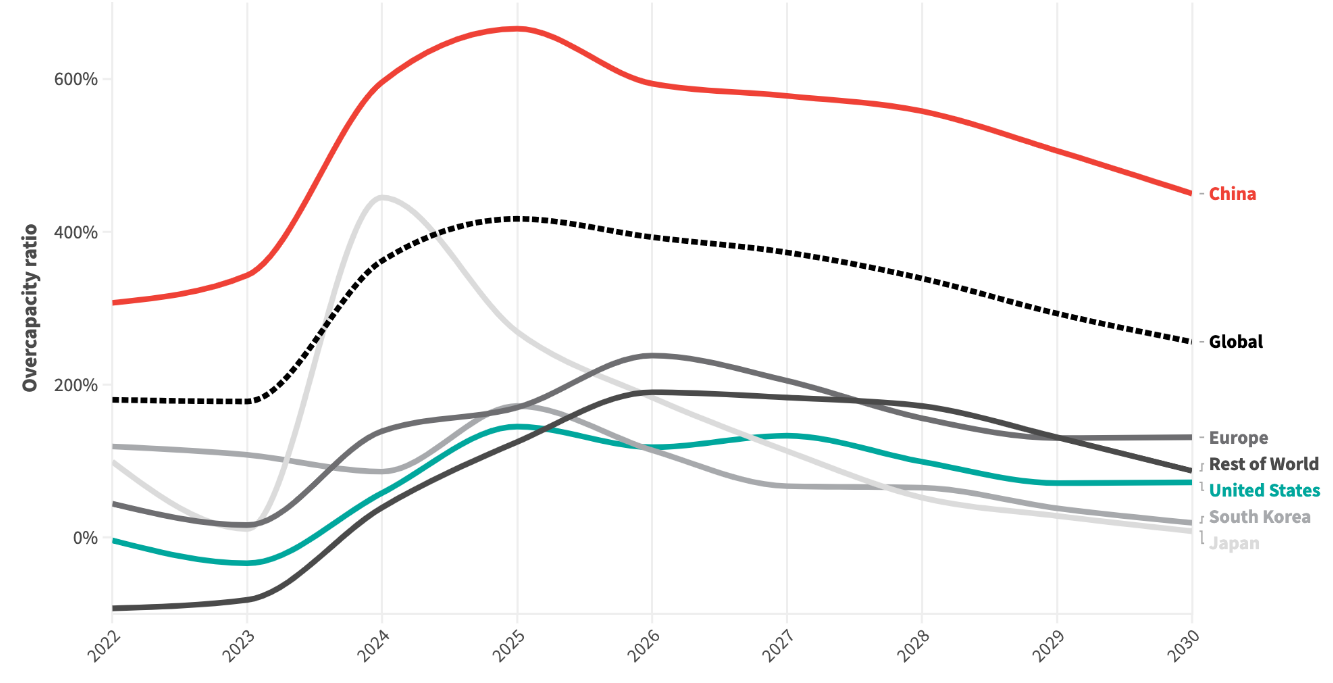

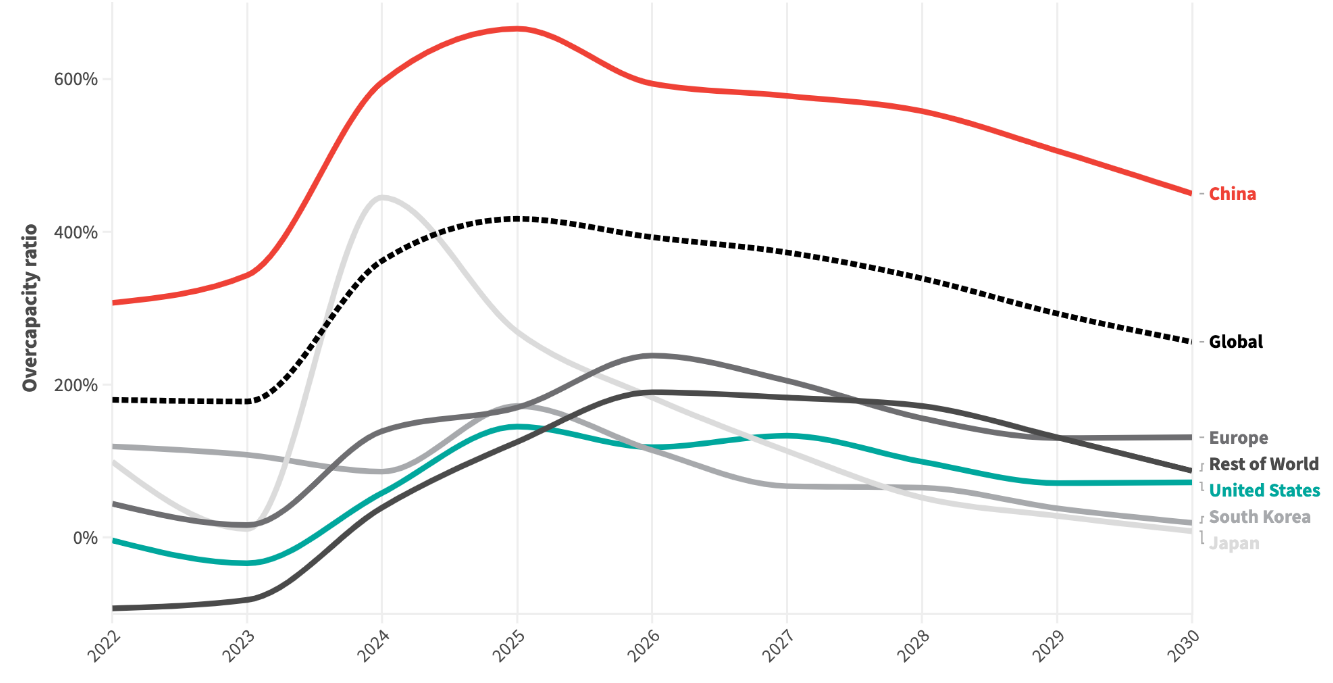

CATL produced 339 gigawatt-hours of batteries in 2024. BYD produced another 154 gigawatt-hours. Together, two Chinese companies supplied more than half of global battery demand. The remaining market shares scatter among dozens of competitors, none of whom approach the scale of the leaders. The third-largest battery manufacturer produces less than one-quarter of what CATL produces.

China refines 81 percent of the world's lithium, even though the ore comes mostly from Australia and South America. Australian mining companies dig lithium out of the ground, ship it to China, and buy back the refined lithium carbonate that goes into batteries. The value addition happens overseas. Chinese companies control 98 percent of lithium iron phosphate cathode production. They control similar shares of graphite anode production and electrolyte manufacturing. The battery may be assembled elsewhere, but the materials inside come from China.

This concentration did not happen by accident. It happened through two decades of industrial policy that prioritized battery manufacturing as a strategic sector. Subsidies for domestic manufacturers. Preferential treatment in domestic markets. Support for capacity expansion even when short-term demand did not justify it. The strategy was not subtle and it was not hidden. Western observers watched it happen and largely failed to respond until the outcome was already determined.

The battery may be assembled elsewhere, but the materials inside come from China.

The cost differentials this concentration produces are not marginal. A turnkey storage system sourced from China costs around $100 per kilowatt-hour. The same capability sourced from American suppliers costs $236. European suppliers, $275. The gap is not labor cost, which represents a small fraction of battery manufacturing expense. The gap is scale, supply chain integration, and accumulated process learning that compounds over thousands of production batches.

The United States Inflation Reduction Act offers tax credits to incentivize domestic battery production. The credits are generous: 30% investment tax credit for manufacturing equipment, additional credits for domestic content, production tax credits that scale with output. The policy aims to make American battery manufacturing cost-competitive through subsidy. Whether it succeeds depends on how fast American manufacturers can climb learning curves that Chinese competitors have already climbed.

The European Union Battery Regulation takes a different approach, imposing supply chain disclosure requirements that complicate imports. Batteries sold in Europe must come with carbon footprint declarations and eventually recycled content certifications. The requirements raise compliance costs for all manufacturers but disproportionately burden those with opaque supply chains. The implicit target is Chinese manufacturers whose supply chain documentation may not meet European standards.

Defense procurement rules will prohibit Chinese battery materials for military applications starting in 2027. The prohibition reflects concern about supply chain security for critical defense systems. Whether similar restrictions extend to civilian infrastructure remains uncertain but the direction of policy is clear.

These measures may slow the growth of Chinese market share in Western markets. They will not reverse the underlying cost advantage within any timeframe relevant to current investment decisions. Building a battery supply chain from scratch requires not just final assembly plants but upstream processing for lithium, cathode precursors, anode materials, electrolyte components. It requires trained workers who know how to operate coating machines and stack electrodes and seal cells without introducing contamination. It requires equipment suppliers and quality testing infrastructure and recycling facilities. None of this appears overnight.

Smart storage systems sit atop a commodity hardware layer dominated by a single country. The algorithms differentiate at the margin, but the hardware determines the base economics. A company with superior algorithms but cells sourced at $275 per kilowatt-hour will struggle to compete with a company whose algorithms are merely adequate but whose cells cost $100. The optimization happens within constraints that geography sets.

Smart energy storage is a battery system that makes its own operational decisions based on continuous monitoring of its physical state and the electricity market. The definition is simple. The implementation is complicated by electrochemistry that degrades in unpredictable ways, markets that reward sophistication until sophistication becomes common, and supply chains that concentrate power in ways that software cannot route around.

The claims that deserve skepticism are the ones that treat the software layer as the primary source of value. Software optimizes at the margin. Chemistry determines the feasible region. Geography determines the cost basis. The intelligence in smart storage is real, but it operates within constraints that the intelligence itself cannot change.

The claims that deserve attention are the ones about battery health monitoring. The ability to detect degradation before it manifests as lost capacity or safety events is where smart systems create value that dumb systems cannot replicate. The algorithms that track subtle changes in charging curves and temperature profiles across thousands of cells are genuinely useful, not because they make batteries better, but because they reveal how batteries are actually behaving underneath the reported voltages.

The timeline claims are the hardest to evaluate. Sodium-ion may reach 30% market share by 2030 or may stall at 5%. Solid-state may commercialize by 2028 or may remain perpetually five years away. Interconnection queues may clear or may continue strangling deployment. Cost curves may continue declining at 20% per production doubling or may hit material limits that bend the curve. Anyone confident about these trajectories is extrapolating from data that does not support confidence.

Storage will matter more in a decade than it matters today. The grid is being rebuilt around variable generation that produces power when the wind blows and the sun shines, not when customers want electricity. Storage bridges that gap. The sophistication of the bridging will increase as algorithms improve and operating experience accumulates. But sophistication is not the point. The electrons need somewhere to go.