What is a UPS Battery Backup Commercial

A UPS battery backup commercial is a commercial-grade uninterruptible power supply system built for business and industrial use, distinct from the consumer-grade units sold at office supply stores. The term can also refer to advertisements for UPS products, though that meaning is secondary. Commercial-grade UPS equipment protects data centers, hospitals, factories, and retail operations from power disruptions that would otherwise cost thousands or millions in downtime, damaged equipment, and lost data.

The difference between commercial and consumer UPS is not merely size or price. Commercial units are engineered for 15-20 year service life in harsh environments, with redundant components, industrial-grade enclosures, and battery systems designed for reliability rather than minimum cost. Consumer units are engineered to survive their warranty period.

The Grid Problem Nobody Talks About

That 99.9% uptime figure utilities quote? Garbage metric for anyone running sensitive equipment.

The number ignores voltage sags, those 50-millisecond dips that never trigger an outage report but absolutely trigger a server reboot. It ignores harmonics bleeding in from the industrial plant down the road. It ignores the switching transient that happens every time the utility company reroutes load at 2 AM. It ignores the neutral-to-ground voltage that slowly corrupts data on improperly grounded systems.

One manufacturing facility documented their "zero outage" year according to utility records. Same year they logged 847 power quality events on their monitoring system. Forty-three of those events caused production disruptions. The utility report and the operational reality existed in different universes.

The IEEE categorizes nine distinct power quality problems: sags, swells, outages, undervoltage, overvoltage, noise, harmonics, frequency variations, and transients. A typical urban commercial building experiences 20-30 of these events monthly. Most go unnoticed because modern equipment has some tolerance built in. But tolerance is not immunity. Each event stresses components, shortens capacitor life, introduces bit errors in storage systems, and nudges equipment toward failure.

Semiconductor fabs figured this out decades ago. A single voltage sag during a wafer processing step can scrap $50,000 worth of product. Those facilities run power conditioning equipment that would embarrass most data centers. The lesson took longer to reach the broader commercial market, but it arrived eventually, carried by the wreckage of corrupted databases and fried servers.

Commercial UPS equipment exists because someone, somewhere, got burned badly enough to write a large check. Nobody installs 2N redundant power infrastructure because they read a whitepaper. They install it because they lost $2 million in a four-hour outage and never want that conversation with the board again.

What Makes Commercial UPS Different

Walk into an office supply store and buy a $150 UPS. Crack it open. Expect a stamped steel enclosure maybe 0.7mm thick, a single cooling fan sourced from the lowest bidder, electrolytic capacitors rated for 2,000 hours at 85°C, and a battery that will be dead in 30 months regardless of what the box claims.

That unit will protect a home computer adequately. Put it in an equipment closet that hits 35°C in summer and the battery will fail in under a year. Nobody at the manufacturer cares. The warranty is 2 years. The business model assumes the customer will buy a replacement when the old one starts beeping.

Commercial equipment starts from different assumptions.

The engineers designing a Liebert or APC SmartUPS unit know the device will sit in a telecom hut in Arizona or a basement electrical room in Houston. They know some technician will kick it while pulling cable. They know the customer expects 15 years of service life and will be furious if they don't get it.

So they specify 10,000-hour capacitors. They use copper transformer windings with thermal headroom. They add redundant fans. They put temperature sensors in the battery compartment. None of this shows up in the marketing spec sheet. All of it determines whether the unit survives past year five.

The Eaton 9PX, a solid choice for mid-size server rooms, has a detail most people miss: the battery connector is designed for tool-free replacement. Small thing. But it means the facilities guy can swap batteries during a maintenance window without calling an electrician. That's 15 years of avoided service calls baked into a $30 connector design. Commercial thinking.

Enclosure Ratings and What They Mean

NEMA ratings tell part of the story. Consumer units meet NEMA 1, which means indoor general-purpose use with minimal protection against dust and liquids. Commercial units typically meet NEMA 12, which handles dust infiltration, dripping water, and oil mist. Industrial units may meet NEMA 4X, which adds corrosion resistance and hose-down capability.

These aren't abstract distinctions. A UPS in a warehouse near a loading dock gets hit with temperature swings every time the bay doors open. A UPS in a food processing plant sees humidity that would rust consumer-grade steel in months. A UPS in a machine shop breathes metal particulate that fouls fan bearings and coats circuit boards.

The enclosure also affects cooling. Commercial units leave room for airflow. Consumer units cram components tight to shrink box size. The commercial unit runs cooler and lives longer. The consumer unit runs hot and dies on schedule.

Component Derating

Commercial engineering uses a concept called derating: specifying components for loads well below their maximum ratings. A 100-amp relay handling 50 amps will last far longer than the same relay handling 95 amps. A capacitor running at 80% of its voltage rating outlives one running at 95%.

Consumer products aim for minimum viable performance. Components run near their limits. Margins are thin. Early failures are accepted as cost of doing business.

Commercial products aim for reliability over service life. Components loaf along at comfortable operating points. Margins are generous. The cost premium exists for a reason.

Heat Management

Heat destroys electronics. Every degree Celsius above 25°C reduces VRLA battery life by approximately 6%. A battery compartment running at 35°C delivers half the service life of one maintained at 25°C.

Commercial systems incorporate oversized heatsinks, multiple redundant fans, intelligent airflow management, and thermal monitoring that adjusts operating parameters based on actual temperatures. Consumer UPS thermal design favors cost and compactness. The commercial unit runs cooler and lives longer.

Three UPS Architectures

Double-Conversion Online

Power comes in. Rectifier converts it to DC. DC charges batteries and feeds the inverter. Inverter generates fresh AC. Load sees only inverter output.

The elegance here: the battery is always in circuit. No transfer time. Zero. When utility fails, nothing changes from the load's perspective. The inverter was already doing all the work.

This architecture dominates data centers because nothing else makes sense at scale. When a single rack holds $400,000 in servers processing financial transactions, the $15,000 premium for online topology over line-interactive is a rounding error.

The old knock on double-conversion was efficiency. Those 2006-era units running 88% efficiency dumped serious heat. Current units from Vertiv and Schneider hit 96% in normal mode, 99% in eco-mode. The efficiency argument is dead.

Double-conversion protects against all nine power quality problems: outages, sags, swells, undervoltage, overvoltage, noise, harmonics, frequency variation, and transients. No other architecture provides this level of isolation.

Line-Interactive

Utility power goes straight to load. An autotransformer handles voltage regulation, boosting when utility sags, bucking when it spikes. Transfer switch flips to battery power when things go sideways.

Transfer time runs 2-6 milliseconds. Modern server power supplies ride through this without blinking. The hold-up capacitors in a decent Dell or HP power supply provide 15-20 milliseconds of buffer.

Good architecture for network closets, branch offices, POS systems. Bad architecture for anything where even theoretical risk of transfer-related glitches is unacceptable. MRI machines, for instance, hate transfer events. The superconducting magnets are touchy about power continuity.

Efficiency reaches 95-98% because power conversion losses occur only during battery operation.

Standby/Offline

Utility power goes directly to load through a relay. UPS monitors voltage and throws the relay when parameters drift.

Transfer time: 8-12 milliseconds. Some equipment cares. Some doesn't.

Fine for desktop computers. Insufficient for anything in a commercial context. Don't waste time evaluating standby topology for business applications.

Specifications That Matter

VA Versus Watts

10 kVA sounds impressive until the realization hits that the unit only delivers 8 kW because the power factor is 0.8.

Here's how this plays out in practice: a buyer sizes a UPS based on nameplate kVA, loads it to 95% of rated VA, and discovers the unit is thermally overloaded because their servers draw 0.99 power factor and they've exceeded the watt limit. The UPS doesn't explode. It just transfers to bypass during a heatwave when protection is needed most.

Modern units increasingly ship with unity power factor. kVA equals kW. Eaton's 93PM, Schneider's Galaxy VX, Vertiv's Liebert EXL S1 all do this. Anyone still evaluating 0.8 power factor units is looking at old inventory or budget-tier equipment.

Size UPS systems at 125% of calculated load to accommodate measurement uncertainty, future growth, and efficiency degradation near maximum ratings.

Runtime Claims

Every manufacturer publishes runtime curves based on new batteries at 25°C with resistive loads.

Real-world batteries aren't new. Real-world electrical rooms aren't 25°C. Real-world loads aren't resistive.

One documented case: a brand-new 30 kVA UPS delivered exactly its specified 14 minutes of runtime on installation day. Same unit, same load, three years later: 6 minutes. Nobody was surprised except the customer, who had never been told that VRLA batteries lose capacity whether they're used or not.

Buy 150% of the runtime that seems necessary. Test under load annually. Replace VRLA batteries at year 3 regardless of what the maintenance tech says about "still testing good."

The relationship between load and runtime is nonlinear. Battery discharge chemistry follows Peukert's Law. Halving the load approximately triples available runtime. A UPS delivering 10 minutes at full load may deliver 30 minutes at half load.

Battery Technology: VRLA Versus Lithium-Ion

VRLA batteries: cheap to buy, expensive to own. Replace every 3-4 years. Heavy. Hate heat.

Lithium-ion batteries: expensive to buy, cheap to own. Replace every 10-12 years (maybe never during UPS service life). Light. Tolerate heat.

The math favors lithium for anything planned to operate more than 6 years. The upfront premium, call it 1.6x, disappears when two battery swap cycles at $8,000-15,000 each are avoided for a typical 20 kVA system.

The real advantage is thermal tolerance. VRLA life halves for every 10°C above 25°C. Lithium-ion barely notices 40°C. Electrical rooms with cooling problems, and most have them, get years of service life back from lithium.

Some IT directors resist lithium because they heard vague things about battery fires. The chemistry in UPS applications (LiFePO4, mostly) is not the same as laptop batteries. Thermal runaway risk is negligible with proper BMS design. Every major manufacturer has validated this in millions of deployed units.

The Hidden Costs of VRLA Battery Replacement

Battery replacement looks simple on paper. Buy new batteries. Swap old for new. Done.

Reality is messier. VRLA batteries weigh roughly 30 kg per 12V/100Ah unit. A 20 kVA UPS might have 20 of them. That's 600 kg of lead-acid batteries that need to come out and 600 kg that need to go in. Elevators have weight limits. Stairwells are narrow. Fork trucks don't fit in server rooms.

The disposal problem is worse. Lead-acid batteries are hazardous waste. Regulations vary by jurisdiction but universally prohibit putting them in a dumpster. Proper disposal requires licensed haulers, manifests, and fees. A battery swap that looks like $4,000 in parts becomes $6,500 after labor and disposal.

Then there's risk. Old batteries can fail during replacement. A shorted cell or dropped unit can take down the entire UPS. Some facilities run replacement procedures with portable backup power standing by, adding another $1,000-2,000 to the project cost.

Lithium-ion batteries weigh 60-70% less. Disposal is simpler (no lead, no acid). Replacement frequency is much lower. The total cost picture favors lithium even when initial purchase price screams otherwise.

Redundancy Configurations

Configuration Overview

N configuration provides exactly the capacity required. Any single failure causes load interruption. This configuration suits only non-critical applications where occasional downtime remains acceptable.

N+1 configuration adds one redundant component beyond minimum requirements. A facility requiring four 50 kVA UPS modules deploys five. Any single module can fail or undergo maintenance without affecting load protection.

2N configuration duplicates the entire power infrastructure. Two completely independent power paths, each capable of supporting 100% of connected loads, guarantee that no single point of failure can cause interruption. This configuration is standard for Tier III and Tier IV data centers, hospital critical care areas, and financial trading facilities.

2N+1 configuration adds redundant components to an already duplicated infrastructure. This configuration exists for organizations where the cost of downtime exceeds the cost of infrastructure by such a wide margin that economic optimization favors maximum protection regardless of expense.

Applications

Data Centers

Half the global UPS market. The Tier system formalizes what everyone already knows: more redundancy costs more money and prevents more disasters.

Tier I means single path, no redundancy, 28 hours of acceptable annual downtime. A startup running staging servers might tolerate this.

Tier IV means 2N everything with concurrent maintainability. Twenty-six minutes of acceptable annual downtime. A trading firm or hospital will accept nothing less.

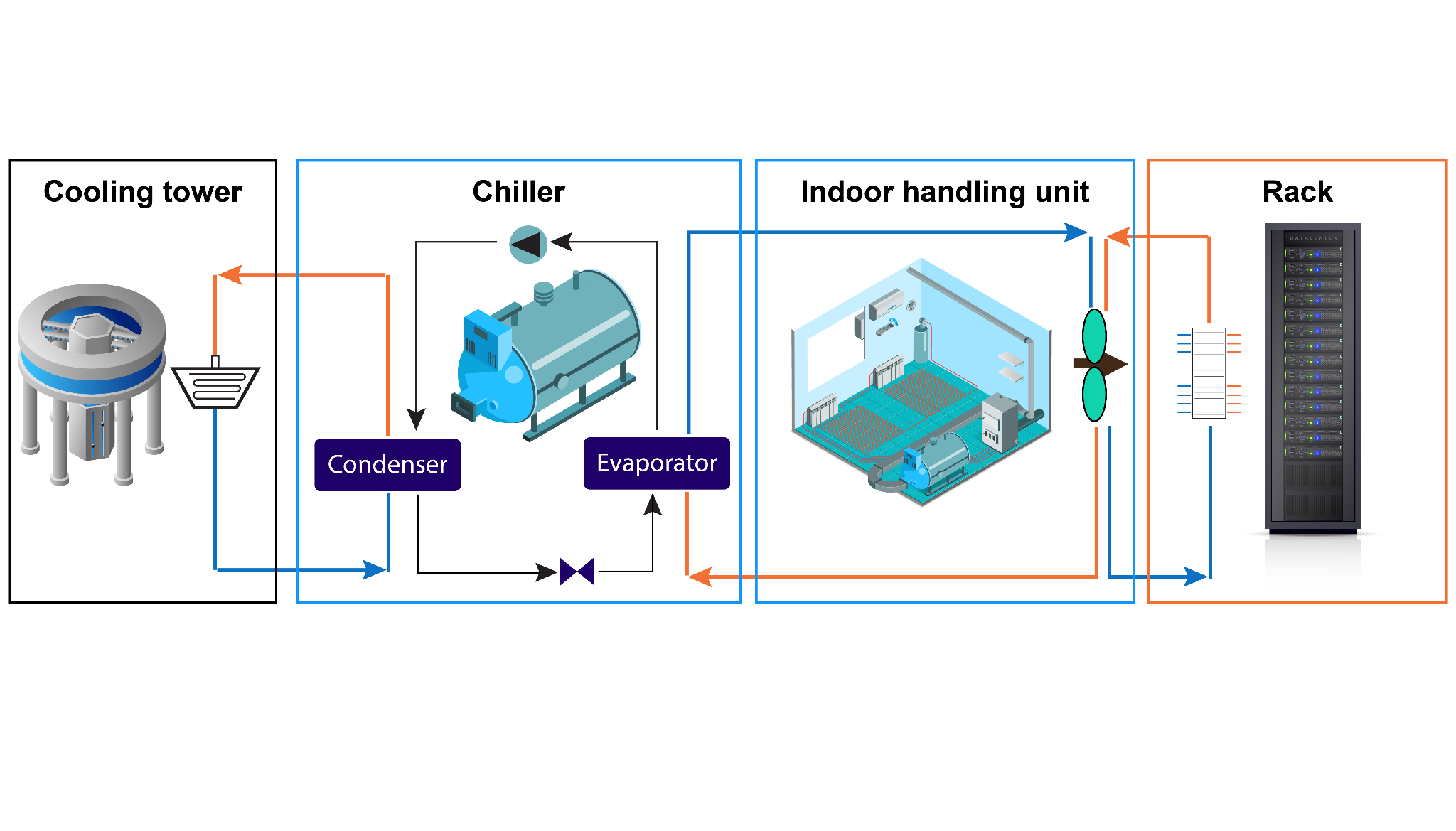

The AI boom is rewriting power density assumptions. A standard rack used to draw 5-8 kW. GPU clusters draw 40-80 kW. UPS vendors are scrambling to deliver solutions that handle this concentration without melting.

What most people miss about data center UPS is the efficiency impact on operating costs. A 1 MW data center running 93% efficient UPS loses 70 kW to heat. That heat requires cooling. The cooling requires more power. The cascade effect means that 7% loss in UPS efficiency translates to roughly 10% higher total facility power consumption. Over 10 years at $0.10/kWh, that efficiency gap costs over $800,000. Suddenly the premium for a 96% efficient unit looks reasonable.

Healthcare

NFPA 99 mandates emergency power within 10 seconds. Generators take 8-15 seconds to come online and stabilize. The UPS bridges that gap.

What NFPA 99 doesn't mandate: quality of the bridge. Some hospitals run line-interactive UPS on critical loads and discover during generator tests that the transfer bumps sensitive monitors. The safe move is double-conversion for anything in an ICU or OR, regardless of what the electrical code technically requires.

Retail

One regional grocery chain calculated their cost of POS downtime at $3,200 per store per hour during peak shopping. Their entire UPS deployment, every register, every payment terminal, every inventory scanner across 200+ locations, cost less than a single day of chain-wide outage.

The refrigeration angle is underappreciated. Compressors don't just stop during outages; they can be damaged by voltage sags and transients that corrupt motor windings. Commercial refrigeration on UPS protection saves equipment, not just inventory.

Manufacturing

Industrial-grade construction justifies its cost in manufacturing environments. A UPS in a plastics plant sees airborne particulate, temperature swings from heating cycles, vibration from nearby presses. Consumer-grade equipment fails in months.

Motor loads add complexity. A 50HP injection molding machine draws 300% starting current. Size the UPS for running load and watch it fold on startup. Experienced integrators specify minimum 1.5x motor nameplate for any UPS supporting industrial motors.

The Vendors

Schneider (APC brand) has the broadest portfolio and deepest channel. For better or worse, APC is the default choice. Every electrical contractor knows how to install and service it. The Galaxy VX series competes at the high end; Smart-UPS dominates the midmarket.

Vertiv (Liebert brand) wins technical evaluations in large data centers more often than market share numbers suggest. Their thermal integration story (UPS plus cooling plus power distribution as a unified system) resonates with hyperscale buyers who hate finger-pointing between vendors.

Eaton owns industrial markets. When a manufacturing plant needs UPS protection for process control, Eaton gets the call. The 93PM series has a loyal following among data center operators who value serviceability.

Huawei sells aggressively on price in Asia-Pacific and increasingly in Europe. Quality is adequate; support is thin outside their core markets.

ABB plays in high-voltage industrial niches that the others can't or won't address. Medium-voltage UPS for utility substations, that kind of thing.

CyberPower captures budget-conscious SMB and gaming segments. Reliability is uneven. Online forums are full of both praise and horror stories. Acceptable for non-critical applications. For anything important, buy elsewhere.

Market Overview

The global UPS market reached $12.1 billion in 2024, growing at 5-8% annually. Data center demand drives above-average growth in the 7-15% range. North America commands 37% market share. Asia-Pacific grows fastest at 9.5% annually.

UPS Product Advertising

The secondary meaning of "UPS battery backup commercial" refers to advertisements for UPS products.

UPS marketing operates predominantly through B2B channels where technical content carries more weight than emotional appeals. Vendors love downtime statistics. "$9,000 per minute" or "$5 million per hour" depending on which analyst report they're citing that week. The numbers are real but misleading. They represent averages across industries with wildly different risk profiles.

Total cost of ownership models deserve skepticism. The vendor controls the assumptions. Of course their 96% efficient unit looks better than the competitor's 94% efficient unit over 10 years when they're projecting $0.15/kWh electricity costs. Did the buyer check the rate their facility actually pays?

Sustainability claims have exploded in recent years. "Carbon neutral by 2030" and similar pledges appear in every pitch deck. Some are backed by genuine engineering investment in efficiency and recyclability. Some are marketing vapor. Ask for specifics.