The Grid-Tied Trap

Most residential solar skips batteries. Panels feed an inverter, the inverter feeds the house, excess flows to the grid, the utility credits the account. Costs stay low. The setup works for years.

Then the grid goes down.

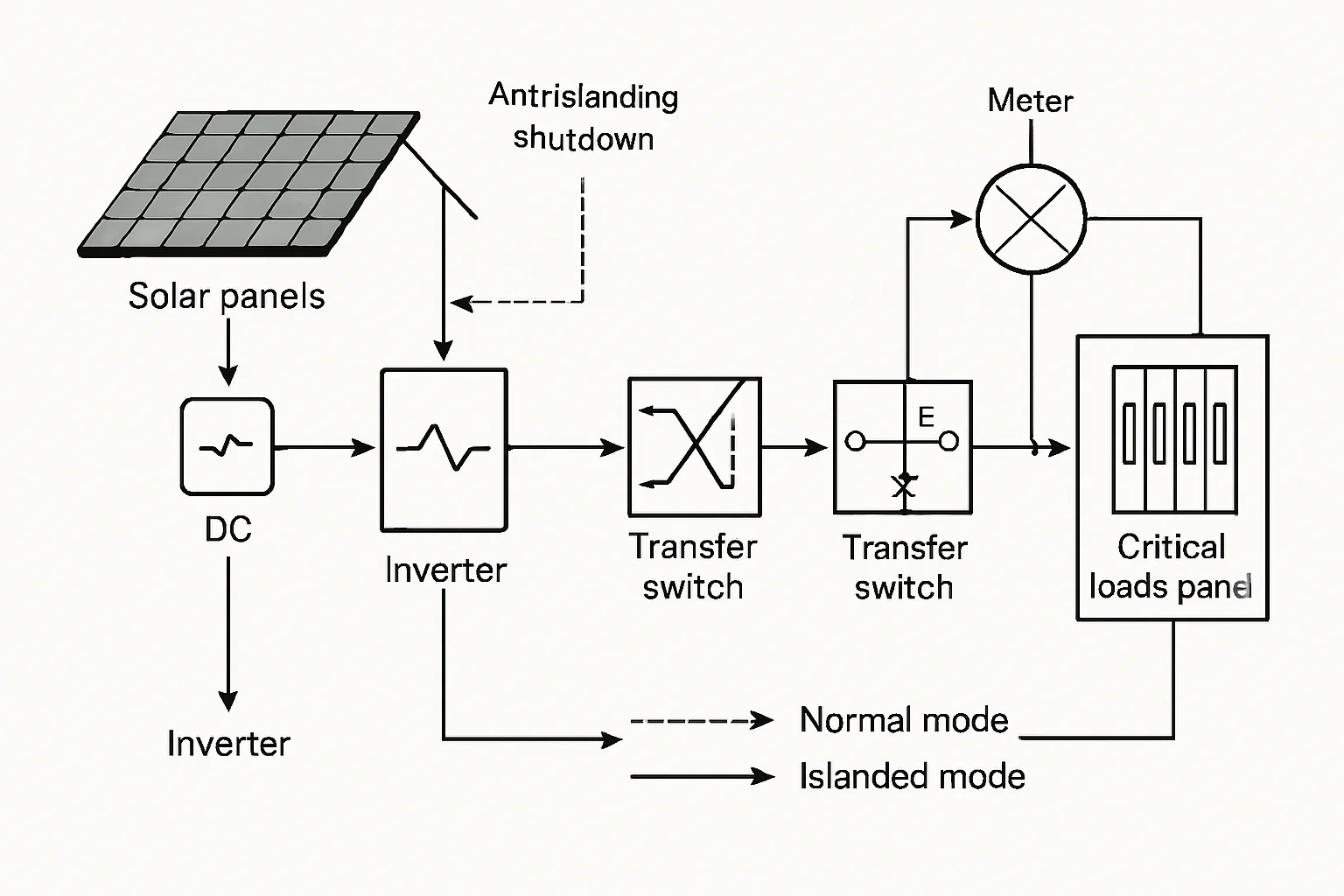

Anti-islanding protection kills the inverter within 200 milliseconds of detecting grid failure. This protects utility workers from electrocution by power feeding back into lines they assume are dead. It also means zero solar power reaches the house during an outage. Panels keep generating. None of it goes anywhere useful.

A $28,000 solar installation producing 9 kW at noon turns decorative the moment a drunk driver hits a utility pole two blocks away. The refrigerator warms. The sump pump sits idle. The homeowner stares at panels doing nothing.

Grid reliability has been declining. Texas froze in 2021 and 4.5 million households lost power, some for over four days. California runs rolling blackouts during heat waves and intentionally cuts power to fire-prone areas during wind events. Pacific Gas & Electric shut off power to 800,000 customers in October 2019 as a fire prevention measure. Hurricane seasons knock out power for days across the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. Puerto Rico went dark for eleven months after Hurricane Maria.

The assumption that electricity will always be available when needed has become questionable in large parts of the country. Homeowners with grid-tied solar watched their systems sit idle through all of these events.

Going fully off-grid solves the reliability problem but the economics collapse. A family using 30 kWh per day needs enough battery capacity to bridge three consecutive cloudy days in winter. That means 90 kWh of storage minimum, more like 110 kWh after accounting for depth of discharge limits. At $400 per kWh installed, battery costs alone hit $44,000. The solar array needs oversizing to charge that bank even during poor conditions, adding another $15,000 to $20,000. Backup generator becomes mandatory for true reliability, plus fuel storage, plus maintenance.

Total cost for a properly designed off-grid system serving a typical American household: $80,000 to $120,000. And that system provides less reliable power than a $150/month utility bill.

Off-grid makes sense for remote cabins where running utility lines costs more than the property. For a house already connected to the grid, it makes no sense at all.

What Hybrid Buys

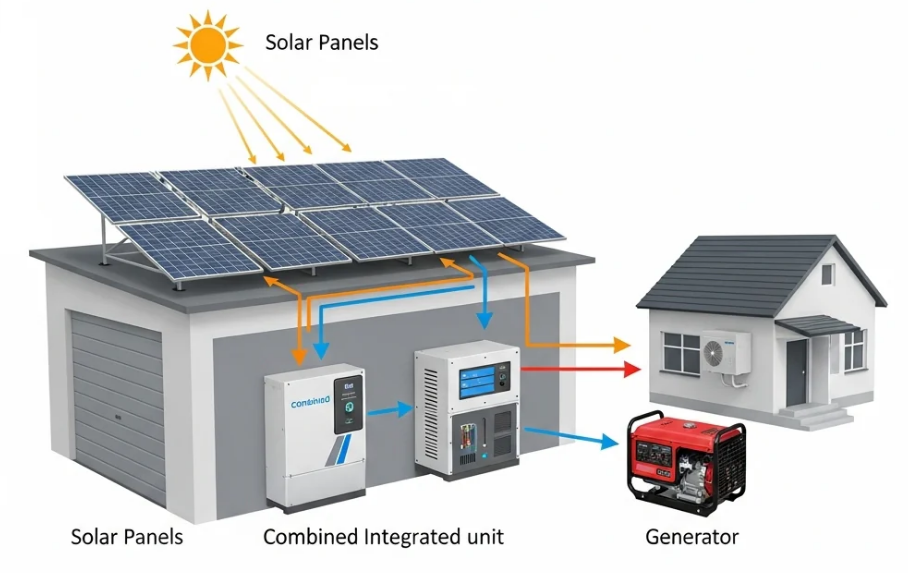

Hybrid keeps the grid connection but adds enough battery storage to matter during outages. The grid handles long-term backup. The battery handles short-term. Each component does what it does best.

A 15 kWh battery pack costs around $9,000 installed. Combined with a hybrid inverter ($3,000 to $5,000 more than a standard grid-tied unit), the total premium over a basic grid-tied system runs $12,000 to $15,000.

That $15,000 buys overnight backup for critical loads: refrigerator, some lights, internet router, phone charging, maybe a small window AC unit. Not the whole house running normally. Not the electric dryer or the EV charger. But enough to keep food from spoiling and maintain communication during a 24-hour outage.

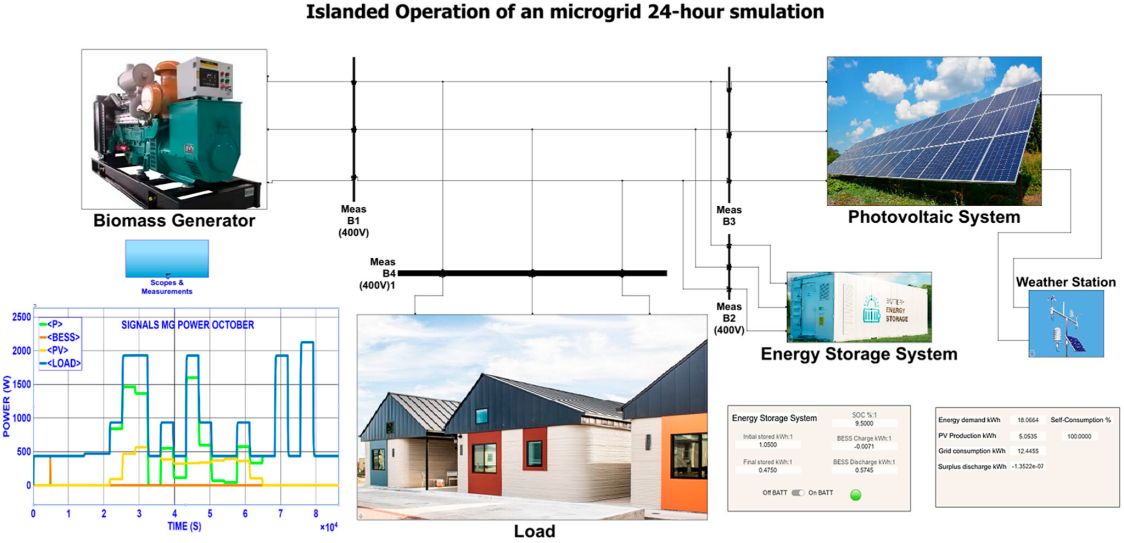

Hybrid systems store midday solar surplus for evening use, dramatically improving self-consumption ratios

The battery also shifts consumption patterns during normal operation. Solar generation peaks at midday. Household consumption peaks in the evening. A battery bridges that gap, storing midday surplus for evening use. Self-consumption ratios jump from 30% on a grid-tied system to 70% or higher with adequate storage.

In areas with time-of-use electricity pricing, the economics improve further. San Diego Gas & Electric charges $0.65/kWh during summer peak hours (4pm to 9pm) and $0.27/kWh overnight. A battery that charges overnight and discharges during peak hours saves $0.38 per kWh cycled, $2,000 per year on a 15 kWh system cycled daily. That cuts the payback period on the battery investment from "never" to seven or eight years.

Batteries

This is where hybrid systems succeed or fail. This is also where the solar industry does its worst work.

Walk into any solar sales conversation. The salesperson will spend twenty minutes on panel efficiency. They will show charts comparing monocrystalline versus polycrystalline. They will explain why their 400W panels outperform the competitor's 395W panels. They will discuss roof angles and shading analysis.

Ask about the battery management system. Watch the blank stare.

The BMS determines whether a $12,000 battery pack delivers fifteen years of service or becomes a replacement expense after five. It is the single most consequential component in a hybrid system. It receives the least attention from buyers and sellers alike.

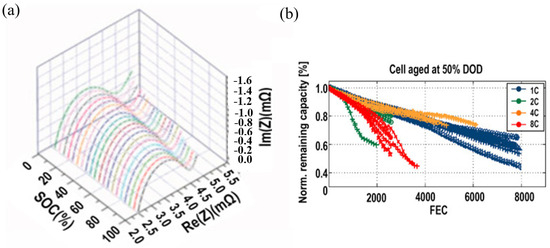

Lithium iron phosphate chemistry offers 4,000 to 6,000 charge cycles before reaching 80% capacity retention

Lithium iron phosphate chemistry dominates residential storage now, and for good reason. LFP offers 4,000 to 6,000 charge cycles before capacity drops to 80% of original. At one cycle per day, that translates to 11 to 16 years of service. Calendar life extends past 20 years at normal operating temperatures.

LFP cells tolerate abuse that would destroy other lithium chemistries. Internal short circuits, overcharging, physical punctures: none of these trigger thermal runaway in LFP the way they do in the nickel-manganese-cobalt cells used in most electric vehicles. For a battery sitting in a garage, potentially unattended for weeks, that safety margin is non-negotiable.

Energy density runs lower than NMC: 150 Wh/kg versus 250 Wh/kg at the cell level. For stationary storage, nobody cares. Weight is irrelevant. The slightly larger physical footprint rarely creates installation problems.

But the cells are only raw material. The battery management system determines real-world performance.

A BMS monitors every cell for voltage, current, and temperature, enforcing charge and discharge limits that protect longevity. Cell balancing algorithms ensure all cells in a pack age at similar rates. State of charge estimation uses coulomb counting to track energy in and out.

So far, standard BMS description. Implementation details separate excellent products from garbage.

Thermal management architecture matters enormously. Cells generate heat during charge and discharge. That heat must be moved away from the cells to prevent accelerated degradation. Some battery packs use passive cooling, relying on ambient air circulation. Others use active cooling with fans or liquid loops. The difference in cycle life between a well-cooled pack and a poorly-cooled pack, using identical cells, can exceed 40%.

Balancing algorithm sophistication matters. A pack contains dozens or hundreds of cells in series and parallel configurations. Manufacturing tolerances mean no two cells are identical. Over time, weaker cells degrade faster, pulling down pack capacity. Active balancing transfers energy from stronger cells to weaker cells during charging, keeping the pack uniform. Passive balancing simply bleeds excess energy from stronger cells as heat, wasting capacity. The difference in usable lifespan between active and passive balancing, again using identical cells, exceeds 20%.

State of charge accuracy matters. An inaccurate SoC estimate means the BMS cannot properly protect the cells from over-discharge or over-charge. A system that thinks it has 20% remaining when it actually has 5% will allow discharge into the danger zone, permanently damaging cell chemistry. Sophisticated SoC algorithms incorporate temperature compensation, aging models, and periodic recalibration. Primitive algorithms use simple voltage lookup tables that drift badly as the pack ages.

Fault detection matters. A single failing cell can drag down an entire pack if not identified and isolated. Quality BMS implementations monitor individual cell impedance trends, catching degradation before it becomes catastrophic. Cheap implementations monitor only pack-level voltage, noticing problems only after significant damage has occurred.

None of this information appears on spec sheets. Manufacturers do not publish balancing algorithms. They do not specify thermal management architecture in buyer-accessible documentation. They do not explain SoC estimation methodology. The information asymmetry between seller and buyer is vast.

Tesla Powerwall has a track record. Millions of units deployed. Third-party teardowns published. Long-term performance data available from independent monitoring services. The Powerwall 2 uses a liquid-cooled NMC pack; the Powerwall 3 switched to LFP. Both have demonstrated real-world cycle life consistent with specifications.

BYD Battery-Box has a track record. The company makes batteries for electric buses and has shipped over a million residential units. Their LFP chemistry and modular design have been validated across multiple climate conditions.

Enphase IQ batteries have a track record. The company started in microinverters and expanded into storage. Their AC-coupled architecture differs from DC-coupled competitors, with tradeoffs in efficiency and installation flexibility.

Franklin WholePower, Generac PWRcell, SonnenCore: these have enough deployment history and published teardown analysis to evaluate. Not all the news is good. Some products have shown higher than expected degradation rates in hot climates. Some have had firmware issues requiring service visits. But the information exists to make informed decisions.

The dozens of white-label products flooding the market from unnamed factories in Shenzhen do not have track records. They have spec sheets listing impressive numbers that may or may not reflect actual performance. They have warranties that may or may not be honored by companies that may or may not exist in five years.

Price difference between a 15 kWh pack from an established manufacturer and a white-label equivalent: maybe $3,000. Lifetime performance difference: potentially $10,000 or more in lost capacity, early replacement costs, and system downtime.

The battery will determine whether the hybrid system delivers value for fifteen years or turns into a maintenance headache after five. Obsess over this purchasing decision. Ignore the panel brand debates that dominate solar forums. The panels are commoditized. The batteries are not.

Power Routing

The hybrid inverter manages all power flows. Solar input, battery charging, battery discharging, grid export, grid import, and house loads all route through this single box.

During normal operation with the grid present, the inverter tracks grid voltage and frequency, injecting current in sync with the utility waveform. Maximum power point tracking algorithms hunt for the best operating voltage on the solar array, adjusting continuously as clouds pass and temperatures change.

Grid failure triggers island mode, where the inverter generates its own AC waveform independent of utility power

Power routing follows a programmed priority stack. Immediate household loads get served first. Remaining solar output charges the battery until it reaches the target state of charge. Any surplus beyond that exports to the grid.

When household loads exceed solar production, the battery discharges to cover the gap. A minimum state of charge threshold, set at 15% on most systems, prevents the battery from fully depleting during normal operation. That reserve stays available for outages.

Grid failure triggers island mode. The inverter detects the outage through voltage and frequency monitoring, opens a contactor to physically disconnect from utility lines, and begins generating its own AC waveform at 60Hz and 240V. The house runs as an isolated microgrid with the inverter as its power source.

Transfer time matters. Premium inverters complete the switch in under 20 milliseconds. SMA Sunny Boy Storage and Fronius Primo GEN24 both achieve sub-20ms transfers. Cheap units take 50 to 100 milliseconds. Computers and networking equipment usually survive 20ms transfers without rebooting. Longer gaps cause problems. Server-grade UPS systems typically specify 10ms maximum transfer time for a reason.

Island mode operation requires continuous balancing. In grid-tied mode, any mismatch between generation and load gets absorbed by the infinite grid. In island mode, the inverter must match supply and demand exactly by modulating battery charge and discharge rates. If loads exceed available power, the inverter either sheds loads or shuts down to protect itself.

Some hybrid inverters support only "critical loads" panels during outages, feeding a subset of circuits rather than the whole electrical panel. Others support whole-home backup but require careful load management to avoid overloading. The installation topology determines what is possible. A system designed only for critical loads backup cannot be upgraded to whole-home backup without rewiring the electrical panel.

Sizing

Array sizing for hybrid systems follows grid-tied logic: match annual production to annual consumption, adjusted for roof orientation, shading, and local solar resource. A house using 10,000 kWh per year in Phoenix needs 6.5 kW of panels. The same house in Seattle needs 9 kW.

Battery sizing depends on backup objectives. For overnight self-consumption, 10 to 15 kWh covers most households. For extended backup of critical loads, multiply daily critical consumption by desired backup hours.

A refrigerator uses 1.5 to 2 kWh per day. Lighting and electronics add 2 to 3 kWh. A small AC unit running half the day consumes 6 to 8 kWh.

Trying to run the whole house normally during extended outages requires far more storage than buyers expect. Electric cooking, clothes drying, water heating, and EV charging push daily consumption past 50 kWh. No residential battery system supports that at reasonable cost.

What Backup Actually Means

A 10 kWh battery does not provide 10 hours of backup at 1 kW load.

Usable capacity after depth of discharge limits drops to 8 kWh. Inverter losses during discharge consume another 6%. Real-world backup from a 10 kWh battery tops out at 7.5 kWh of delivered energy.

That 7.5 kWh keeps a refrigerator, a few lights, and phone chargers running for 36 to 48 hours. Add a window AC unit and runtime drops to 8 to 12 hours. Add a well pump with a 1 HP motor and runtime drops further because motor starting surge may exceed inverter capacity, causing shutdown.

Extended outages during cloudy weather create a recharging problem. A 10 kWh battery needs 12 to 13 kWh of solar input to refill after charging losses. On a heavily overcast day, a 6 kW array might produce only 8 to 10 kWh total. The battery may not fully recharge before the next evening's discharge cycle begins.

Winter compounds the problem. A system that produces 35 kWh daily in June may produce only 12 kWh daily in December at the same location. Household consumption often increases in winter due to shorter days and supplemental heating. The gap between winter production and winter consumption requires significant grid import regardless of battery capacity.

Buyers consistently overestimate backup capability. A salesperson mentions "10 kWh battery" and the buyer imagines running the house normally for a day. Actual capability: refrigeration, lights, and internet for one to two days, or the whole house for a few hours. Setting expectations correctly before purchase prevents disappointment during actual outages.

The Economics

Grid reliability problems justify hybrid investment better than economic calculations. A household in an area with frequent outages, whether from weather, aging infrastructure, or deliberate utility shutoffs during fire season, gets genuine value from backup capability.

High time-of-use rate differentials make hybrid economics work even without outages. The $0.38/kWh spread in San Diego pays for battery storage over its lifetime. The $0.08/kWh spread in most other markets does not.

Medical equipment requiring uninterrupted power creates non-negotiable backup requirements.

Anticipation of future load growth from EV charging or heat pump installation argues for hybrid infrastructure that can adapt to higher self-consumption needs.

Stable grids with infrequent outages eliminate the primary value proposition. A household in an area that experiences one four-hour outage per year cannot justify $15,000 in battery investment on backup value alone.

Flat electricity rates without time-of-use differentials eliminate arbitrage value.

Limited budgets get more value from larger solar arrays than from smaller arrays plus batteries. An extra $15,000 of panels generates 7,500 kWh annually for 25 years, totaling 187,500 kWh. That same $15,000 in batteries might save 2,000 kWh annually in grid purchases while providing occasional backup value.

Installation

Solar installation is construction work on rooftops and in electrical panels. Quality varies as much as any other trade. The lowest bidder often delivers the worst long-term value.

Installation quality varies dramatically between contractors, affecting system performance for decades

Roof attachments can leak if flashing details get botched. The leak may not appear for years, by which point water damage has spread through the roof deck. Good installers understand roofing as well as solar. Many do not.

Wire sizing errors cause voltage drop that costs efficiency for the entire life of the system. A 3% voltage drop on the DC side means 3% less energy reaching the inverter every single day. Over 25 years, that loss adds up to thousands of dollars.

Commissioning often gets rushed. Battery charge parameters should match manufacturer specifications for the specific chemistry. Export limits must comply with utility interconnection requirements. Backup transfer should be tested under simulated outage conditions. Systems that skip these steps operate for years with suboptimal settings that nobody notices because nobody checks.

The Calculation

A hybrid solar system combines grid connection with battery storage to capture the economic benefits of grid exchange while providing backup power during outages.

The value depends entirely on local conditions: grid reliability, electricity rate structures, backup power needs, available budget. For some households, hybrid systems offer capability that grid-tied systems cannot match. For others, they represent expensive insurance against risks that may never materialize.

The battery decision dominates everything else. A quality battery pack from an established manufacturer with a real track record and a meaningful warranty will cost more upfront. It will also still be working in year twelve when the cheap alternative has already been replaced twice. The economics favor paying more for the battery and less for everything else in the system.

Everything about the technology works. What remains unclear is whether any particular household benefits from paying for it.