What is 12V Lithium Battery Charger?

Victron stopped shipping the Blue Smart IP22 with lead-acid default settings sometime in 2022. The change came after too many support tickets from customers who had fried their LiFePO4 packs by not switching the DIP configuration. Progressive Dynamics still ships their PD9260C converter with a 13.6V float that will slowly murder any lithium house bank connected to it. Battle Born publishes a compatibility list on their website that runs eleven pages and still misses half the edge cases people encounter in the field.

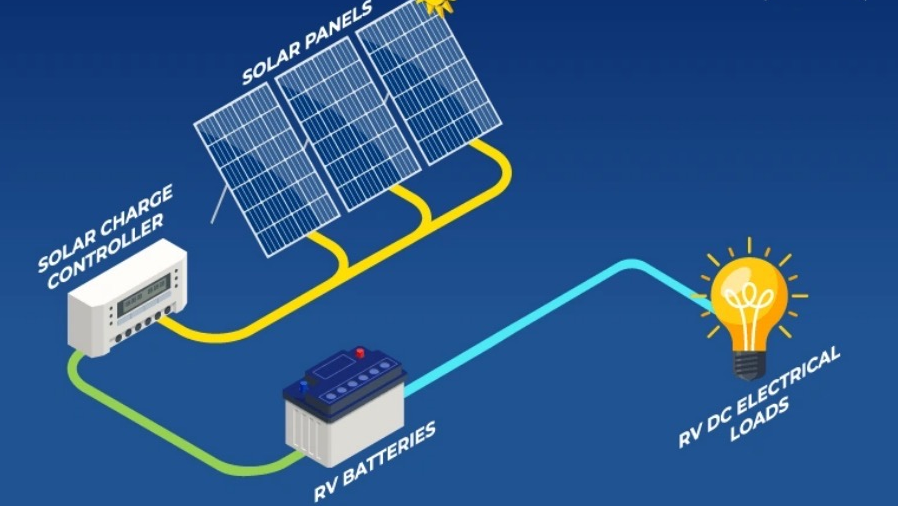

Modern lithium battery charging systems require precise voltage control

The 12V lithium battery charger market is a mess. Not because the technology is complicated-the CC/CV charging algorithm dates back decades-but because the industry spent forty years building infrastructure around lead-acid assumptions. RV converters, marine chargers, solar controllers, automotive alternators, UPS systems: all of it calibrated for a chemistry that tolerates sloppy voltage management. Lithium does not tolerate sloppy voltage management. The mismatch destroys batteries.

A proper 12V lithium battery charger terminates at 14.2V to 14.6V depending on cell specification, holds no float voltage, and refuses to push current below freezing. That description covers maybe 15% of the charging equipment currently installed in boats and RVs across North America. The other 85% is degrading lithium batteries right now, and the owners have no idea.

The Voltage Problem

Renogy specs their 12V LiFePO4 batteries for 14.4V maximum charge. SOK rates theirs at 14.6V. Ampere Time lists 14.6V on their 100Ah but 14.4V on their 200Ah due to different cell sourcing. EG4 server rack batteries want 14.2V because they use prismatic cells from a different supplier than the cylindrical packs everyone else sells.

The industry has no standard. Each manufacturer sources cells from CATL, EVE, Lishen, CALB, or whoever offered the best price that quarter, then builds packs around whatever voltage curve those cells provide. A charger that works perfectly with one brand will slowly overcharge another brand.

LiFePO4 cells from different manufacturers have varying voltage specifications

This matters because lithium iron phosphate degradation follows an exponential curve with voltage. Researchers at Sandia National Laboratories published calendar aging data in 2019 showing LiFePO4 cells stored at 3.65V per cell lost capacity roughly twice as fast as identical cells stored at 3.3V. The relationship holds during charging: cells pushed to 3.67V degrade noticeably faster than cells held to 3.60V.

Translate to pack level: a charger pushing 14.6V into a battery rated for 14.4V adds maybe 50mV overvoltage per cell. Does not sound like much. But that 50mV might cut cycle life from 3500 cycles to 2800 cycles based on the Sandia data extrapolation. Nobody will notice for two years. Then the capacity measurements come in low and everyone blames the battery manufacturer.

The nastiest part: most chargers cannot hold voltage accurately enough to matter. The Noco Genius 10 specs ±2% regulation, which means its 14.4V lithium mode might actually output anywhere from 14.1V to 14.7V. That 14.7V output will overcharge every LiFePO4 battery on the market.

Sterling Power publishes ±1% specs on their ProCharge Ultra line, tightening the window to 14.3V-14.5V. Still not great if the battery really wants 14.2V.

Meanwhile the marketing departments keep printing "lithium compatible" on boxes without defining what that means.

The forums are full of threads about this. A poster on the Victron Community board discovered their Blue Smart IP67 charger measured 14.78V at the terminals despite being set for the 14.4V lithium profile. Manufacturing variation. Within spec if you read the fine print. Fatal to batteries expecting tight voltage control. Victron's response suggested using an external Bluetooth dongle to fine-tune the voltage setpoint. Most users never knew such adjustment was possible.

A thread on cruisersforum ran 47 pages debating whether the Balmar MC-614 alternator regulator could safely charge LiFePO4 banks. The manufacturer claimed lithium compatibility. Users reported wildly different voltage outputs depending on firmware version, temperature, and which production batch the regulator came from. Some units held 14.2V rock steady. Others drifted to 14.9V under certain load conditions. The discussion never reached consensus because Balmar kept revising the firmware without publishing version notes.

This is the state of the industry in 2024: even premium equipment from reputable manufacturers requires verification after installation. Trust nothing printed on boxes. Measure actual voltage under actual charging conditions. If the numbers do not match expectations, adjust or replace.

How Lithium Charging Actually Works

Skip this section if electrochemistry puts you to sleep. But understanding the mechanism explains why lead-acid settings cause lithium damage.

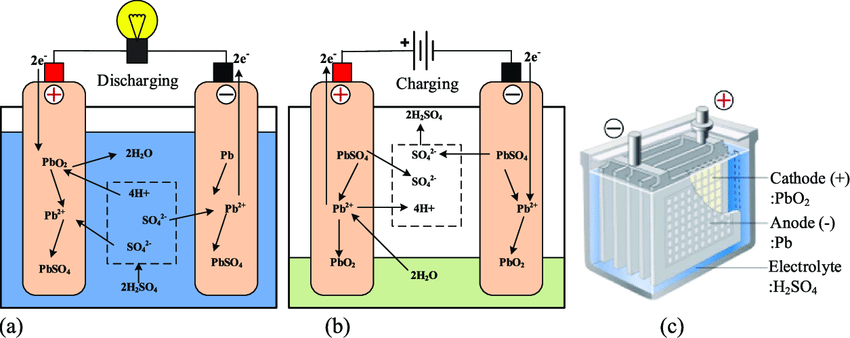

A lithium iron phosphate cell contains three active layers. The cathode is olivine-structure LiFePO4, which stores lithium in crystallographic tunnels between iron and phosphate groups. The anode is graphite, which stores lithium between hexagonal carbon sheets. The electrolyte is typically LiPF6 salt dissolved in organic carbonates-ethylene carbonate, dimethyl carbonate, diethyl carbonate in various blends depending on manufacturer.

Battery electrochemistry for proper charging

Charging moves lithium from cathode to anode. The external voltage provides energy to extract lithium ions from the cathode crystal structure, push them through the electrolyte, and insert them into the graphite. The 3.2V nominal cell voltage reflects the energy difference between lithium bound in LiFePO4 versus lithium intercalated in graphite. At full charge, approximately LiC6 stoichiometry in the anode and FePO4 in the cathode.

The solid-electrolyte interphase forms on the graphite surface during first charge. SEI is a passivating layer maybe 20-50 nanometers thick composed of lithium carbonate, lithium fluoride, and various organic decomposition products. Good SEI protects the graphite from continued reaction with the electrolyte. Bad SEI-thick, resistive, unstable-consumes lithium and raises impedance.

Overvoltage accelerates SEI growth. The electrolyte reduction reactions that form SEI are thermodynamically favored at the low potentials graphite reaches during full charge. Higher voltage pushes the graphite to lower potential, increasing SEI formation rate. The relationship is roughly exponential in overpotential according to Butler-Volmer kinetics. Each 50mV of excess voltage might double or triple the parasitic SEI growth rate.

Underpotential during float is different but also bad. Lead-acid float holds the battery at a voltage where self-discharge equals trickle charge. For LiFePO4, a 13.6V float corresponds to roughly 40-50% state of charge depending on cell discharge curve. The battery never reaches full capacity. The BMS never sees the voltage endpoints needed for accurate SOC calibration. Capacity reporting drifts. Users think they have 100Ah but actually get 60Ah because the gauge is wrong.

There is a reason nobody publishes long-term float data for LiFePO4 cells. The degradation is slow and hard to separate from normal calendar aging. But talk to anyone who has run lithium house banks for five years and a pattern emerges: batteries kept on continuous shore power float age faster than batteries cycled regularly. The conventional wisdom from lead-acid-that keeping batteries topped off is good-inverts for lithium. A LiFePO4 cell is happiest sitting at 50% state of charge, not 100%.

The only published data supporting this comes from NASA and the electric vehicle research community. Calendar aging studies for 18650 cells showed capacity retention correlating inversely with storage state of charge. Cells stored at 4.2V (100% SOC) lost capacity roughly three times faster than cells stored at 3.7V (40% SOC) over 12 months at 25°C. The chemistry differs between NMC and LFP, but the trend holds: higher voltage means faster parasitic reactions mean shorter life.

The BMS Makes Everything Harder

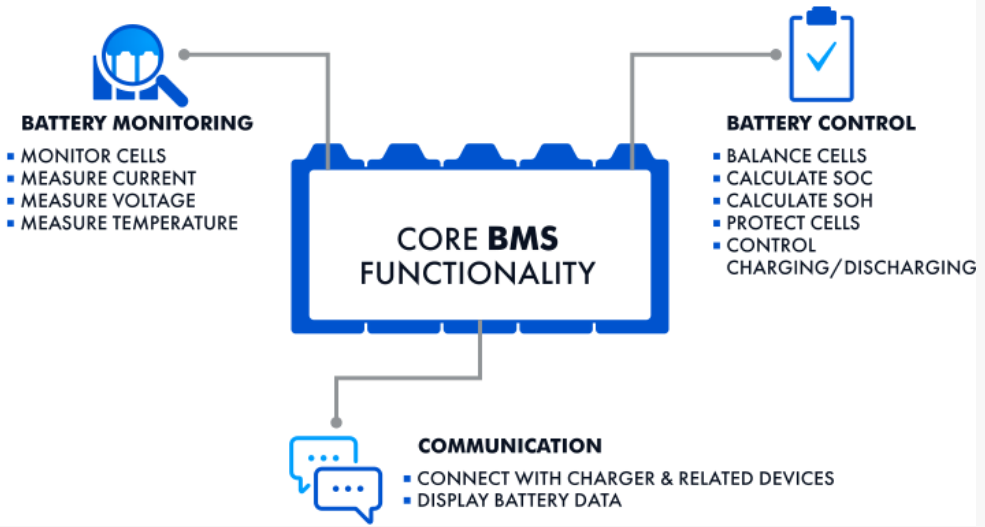

Battery management systems ship with protection thresholds set by whoever designed the BMS firmware-usually not the same company that sells the battery to end users.

Overkill Solar sells a popular 16S 48V BMS that defaults to 58.4V charge cutoff (3.65V/cell). Daly BMS ships with 54.6V default on their 48V units (3.41V/cell). Both get rebranded and sold under dozens of names with documentation that may or may not match actual firmware settings.

Battery Management Systems control charging behavior through firmware settings

At 12V scale, the JBD/Xiaoxiang BMS that appears in many budget LiFePO4 packs defaults to 14.6V cutoff with a 100mV release hysteresis. Meaning the BMS disconnects at 14.6V, waits for voltage to drop to 14.5V, then reconnects. If the charger is still pushing, voltage shoots back to 14.6V and the cycle repeats. Each protection trip stresses the BMS MOSFETs. Each inrush current spike heats the connector terminals.

Configuring BMS parameters requires either Bluetooth (JBD app, Overkill app) or serial connection (Daly, JK). Most retail customers never change defaults. The BMS does what it does regardless of what the battery label claims.

This creates bizarre interactions. A Battle Born BB10012 contains a proprietary BMS that disconnects at 14.6V and reconnects at 14.4V. Connect it to a charger holding 14.5V float and the battery sits in an endless connect-disconnect loop. Battle Born support will tell you to use a charger with no float stage. Their documentation lists approved chargers. The list does not include most of the equipment people already own.

Temperature Kills Batteries Quietly

The lithium plating problem at low temperature is well documented in academic literature but poorly understood by installers.

Jeff Dahn's group at Dalhousie University published cycling data in the Journal of the Electrochemical Society showing lithium plating onset at charging rates above C/3 when cell temperature dropped below 10°C. At 0°C, even C/10 charging showed plating signatures in differential capacity analysis. At -10°C, any charging current caused measurable plating.

Plated lithium does not intercalate. It sits on the graphite surface as metallic lithium, electrochemically isolated from normal charge-discharge reactions. Capacity drops proportionally. Worse, plated lithium tends to form in dendritic structures-microscopic needles growing perpendicular to the electrode. Dendrites that reach the separator and puncture through cause internal short circuits.

Most lithium battery fires trace to manufacturing contamination (metal particles piercing separators) or physical damage (crush, puncture). But cold charging adds a failure mode that accumulates invisibly. The battery works. It just works less well. Capacity measurements drift downward. Internal resistance creeps upward. By the time anyone notices, years of cold-temperature charging have deposited enough plated lithium to noticeably impact performance.

Heated battery blankets exist for this reason. Victron sells the Smart BMS CL 12/100 with built-in heating element that activates below 5°C. LiTime markets heated versions of their LiFePO4 packs with internal heating elements powered by the battery itself during cold starts. The heating adds $75-150 to battery cost but prevents the silent degradation that ruins unheated packs over northern winters.

What Chargers Actually Exist

The market segments roughly into four categories:

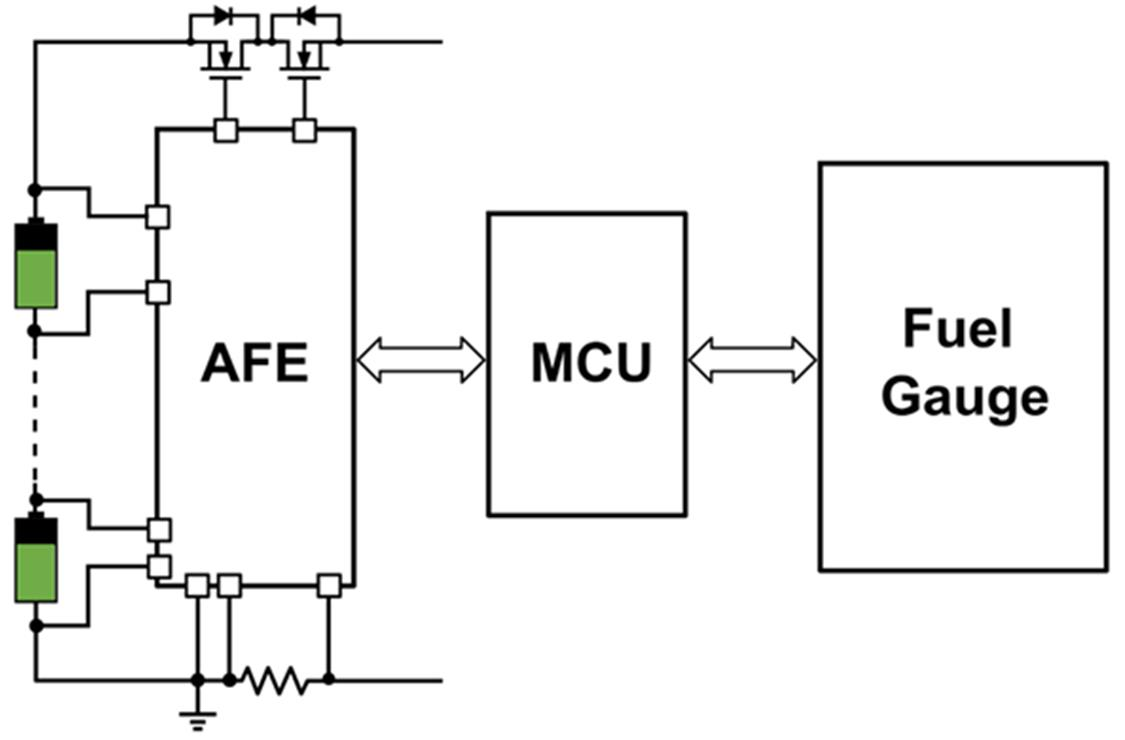

Dedicated lithium chargers designed from the start for LiFePO4 chemistry. Victron Blue Smart series, NOCO Genius lithium modes, Sterling Power ProDigital. These terminate at manufacturer-specified voltage, hold no float, include temperature compensation, and usually offer configurable parameters via Bluetooth or DIP switches. Price runs $89-450 depending on amperage and features.

Professional-grade charging equipment offers precise voltage control

Multi-chemistry chargers with selectable profiles. Battery Tender, Schumacher, CTEK, most of what Walmart and Amazon sell. Lithium modes exist but default settings may not match every battery. Documentation often fails to specify exact voltage output in lithium mode. Quality varies enormously between models. Some hold voltage within ±0.5%, others within ±3%. The spec sheets do not always tell you which you are getting.

RV converters and marine chargers designed for lead-acid and later retrofitted with lithium settings. Progressive Dynamics Charge Wizard, WFCO WF-9800 series, Magnum Energy inverter-chargers. Some models accept firmware updates that add lithium profiles. Others require hardware modification or complete replacement. Installing lithium house banks in RVs and boats often requires upgrading charging infrastructure that came standard with the vehicle.

DIY and industrial chargers. Mean Well HLG series LED drivers repurposed as lithium chargers-constant-current to preset voltage with no float. Chargery power supplies popular in the RC and EV communities. These work well for people who understand power electronics and terribly for people who do not.

The Mean Well hack has a cult following on the DIY solar forums. The HLG-320H-48B is a 320W LED driver that outputs constant current until the load voltage reaches 48V, then holds constant voltage. It has no microprocessor, no charging algorithm, just analog current limiting and voltage regulation.

Swap the output capacitors to raise voltage to 54V and the unit becomes a perfectly adequate 48V lithium charger. Add a temperature-controlled relay and you have cold protection. Total cost runs $65 versus $400 for a comparable commercial lithium charger.

The DIY approach works because CC/CV charging is not complicated. A proper lithium charger is just a current-limited power supply with accurate voltage regulation. All the Bluetooth apps and firmware updates and selectable profiles are conveniences layered on top of simple underlying electronics. Anyone comfortable with a soldering iron can build or modify their own charging equipment for a fraction of commercial cost.

The danger is that DIY charging equipment has no certification, no protection against manufacturing defects, no recourse if something fails. An HLG LED driver modified for battery charging will not be UL listed for that application. Insurance companies may dispute claims involving non-certified electrical equipment. Commercial installations should use commercial chargers regardless of cost differential.

The recurring theme: getting lithium charging right requires matching charger output to battery specification within maybe ±100mV. Most equipment sold as "lithium compatible" hits that target only under ideal conditions. Temperature drift, line voltage variation, manufacturing tolerance, and aging all push actual output away from nameplate specs.

Selection Comes Down to Reading Datasheets

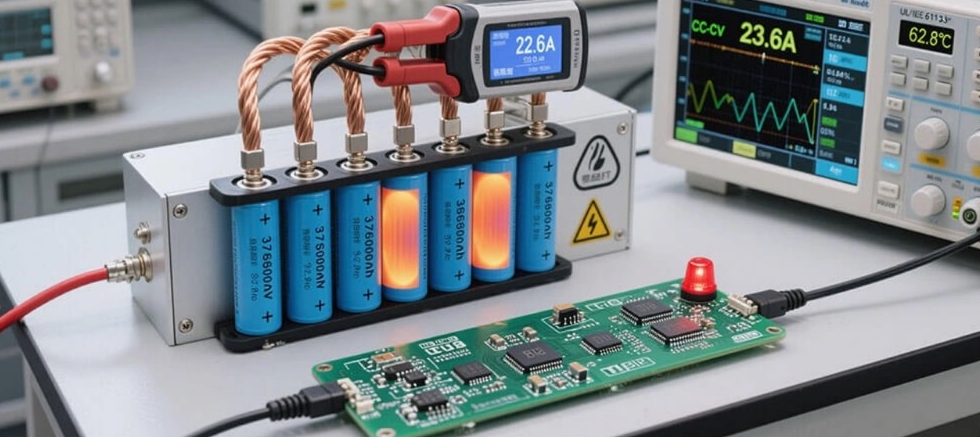

The battery datasheet lists maximum charge voltage. Write it down. The charger datasheet lists output voltage in lithium mode and regulation tolerance. Multiply tolerance by nominal voltage. Check whether the worst-case high output exceeds battery maximum. If yes, pick a different charger.

Real example: Ampere Time 12V 100Ah specifies 14.6V maximum. NOCO Genius10 specs 14.4V output with ±2% regulation. Worst case high: 14.4V × 1.02 = 14.69V. That 90mV overshoot probably will not destroy the battery immediately but will accelerate degradation slightly. Whether that matters depends on how many cycles you need.

Real example: Renogy 12V 100Ah Smart Lithium specifies 14.4V maximum. Same NOCO charger worst case outputs 14.69V, now overshooting by 290mV. That will cause noticeable capacity loss over a few hundred cycles.

Proper charger selection requires careful datasheet analysis

A battery dealer in Arizona posted his warranty return data on a solar forum in 2023. Out of 847 LiFePO4 batteries sold over two years, 23% came back with capacity complaints. The dealer tested every return and found that 89% of the "defective" batteries had been charged with equipment outputting between 14.7V and 15.1V. In most cases the customers had no idea their chargers ran high. They blamed the batteries. The batteries were fine when sold. The chargers destroyed them.

This dealer now refuses to sell lithium batteries without verifying customer charging equipment first. Sales dropped 15% because some customers walked away rather than buy a new charger. Warranty returns dropped 80%. The math worked out in his favor, but he was the exception. Most retailers sell batteries without questions because asking questions loses sales.

The arithmetic is tedious. Most people skip it. They connect whatever charger they own, observe that the battery charges, and assume compatibility. The assumption holds until capacity measurements start coming in low two years later.

Temperature compensation adds another variable. Most lithium chargers reduce voltage at elevated temperature-typically -10mV to -20mV per degree Celsius above 25°C reference. At 45°C, a charger nominally set for 14.4V might output 14.0V-14.2V. Good for battery longevity. But the compensation curve varies between manufacturers and documentation does not always specify slope.

Cold temperature lockout is binary: either the charger refuses current below some threshold (typically 0°C or 5°C) or it does not. Chargers without lockout will happily charge frozen batteries. The batteries will accept current and appear to charge normally while plating lithium internally. Check whether your charger has cold lockout before winter.

The Industry Created This Problem

Lead-acid charging is simple because lead-acid tolerates abuse. Overcharge a flooded lead-acid battery and it gasses hydrogen, loses water, maybe buckles a plate eventually. But it keeps working for years even with sloppy voltage control. Gel and AGM batteries are more sensitive but still accept float charging indefinitely without catastrophic failure.

Lithium demands precision the legacy infrastructure was never designed to provide. RV manufacturers kept shipping Progressive Dynamics converters long after lithium house banks became common because the converters worked fine with the AGM batteries that were standard equipment. Boat manufacturers did the same with marine chargers. The upgrade path requires either swapping charging equipment or adding external regulators to existing equipment-complexity that vendors avoid mentioning in marketing materials.

Some lithium battery manufacturers responded by building wide-tolerance packs that survive connection to lead-acid chargers. Battle Born advertises "drop-in replacement" for this reason: their BMS is configured to disconnect before damage occurs even when connected to improperly configured chargers. The tradeoff is reduced effective capacity because the BMS triggers protection at voltage thresholds lower than optimal for cell longevity. A battery rated at 100Ah might deliver 85Ah in practice because the BMS disconnects early to protect against charger overshoot.

Other manufacturers spec their batteries tightly and expect customers to use matching chargers. SOK and EG4 documentation reads like it was written for engineers: cell-level specifications, detailed voltage curves, thermal derating tables. Excellent if you understand the information. Useless if you just want something that works with the charger you already own.

Practical Guidance

Buy a charger designed for LiFePO4 from the start. Do not trust multi-chemistry modes unless the documentation specifies exact voltage output and tolerance.

Match charger voltage to battery spec with margin. If the battery wants 14.4V, pick a charger that outputs 14.2V-14.3V. The slight undercharge loses maybe 5% capacity but eliminates overvoltage risk entirely.

Install temperature sensing if the charger supports it. External sensors cost $15-30 and prevent both hot overcharge and cold plating damage.

Avoid float charging. The charger should terminate after reaching voltage target, not hold indefinitely. If your existing charger lacks this option, add a disconnect relay on a timer.

Check BMS configuration. If the battery uses a JBD, Daly, or JK BMS, download the app and verify protection thresholds match charger output. Adjust if needed.

Store at partial charge. Lithium batteries stored at 100% SOC degrade faster than batteries stored at 50% SOC due to elevated SEI formation rate. For seasonal storage, charge to 50-60%, disconnect, check voltage monthly.

Proper charging setup is essential for solar and off-grid applications

The boring answer is that lithium charging requires reading two datasheets-charger and battery-and doing basic arithmetic to confirm compatibility. The industry makes this harder than necessary by publishing incomplete specs, using inconsistent terminology, and marketing "lithium compatible" equipment that might or might not work with any given battery.

The technology is not new. CC/CV charging has been standard for lithium-ion since the 1990s. The problem is legacy infrastructure, mismatched equipment, and marketing that values "drop-in replacement" messaging over technical accuracy. A 12V lithium battery charger is just a power supply that stops at the right voltage. Getting that right should not be this complicated. But it is.

The frustration compounds because the solutions exist. Victron, Wakespeed, Sterling Power, Mastervolt, and others make charging equipment that works correctly with lithium batteries. The equipment costs more than the junk at Walmart but less than replacing a battery bank destroyed by the junk at Walmart. The problem is not technology. The problem is that correct information does not reach buyers until after they have made purchasing decisions.

Walk into any RV dealership and ask about lithium compatibility. The salespeople will assure you that everything is lithium compatible now. It is not. The 2024 Airstream Basecamp ships with a WFCO converter that floats at 13.6V. The 2024 Forest River Wildwood ships with a converter that peaks at 14.8V. Neither setting is correct for lithium. Both salespeople will tell you the RV is lithium ready.

The term "lithium ready" has no agreed definition. Some manufacturers mean the electrical system can physically connect to lithium batteries. Some mean the charging equipment includes a lithium mode that may or may not be properly configured. Some mean absolutely nothing-just a marketing phrase that sounds good. Buyers have no way to know which interpretation applies until they read the installation manual or measure voltage with a multimeter.

Experienced installers recommend buying battery and charger from the same manufacturer when possible. Victron batteries with Victron chargers. Battle Born batteries with chargers from Battle Born's approved list. EG4 batteries with EG4-specified charging parameters. The compatibility testing has been done. The settings are documented. The support calls get answered by people who understand both products.

Cross-brand combinations work too, but require the datasheet comparison described above. And require accepting that neither manufacturer will take responsibility if something goes wrong. The battery manufacturer will blame the charger. The charger manufacturer will blame the battery. Both will blame the installer. Everyone covers their liability. Nobody solves the problem.

After enough frustration, the real question stops being "what is a 12V lithium battery charger" and becomes "why is this so hard." The answer involves forty years of lead-acid infrastructure, a supply chain that prioritizes cost over specification accuracy, marketing departments that discovered "lithium compatible" sells products, and an industry that has not agreed on basic terminology. The charging technology is simple. The ecosystem around it is a disaster.