A 12-volt lithium battery is, at its simplest, a pack of lithium cells wired together to reach approximately 12 volts—the same voltage profile that lead-acid batteries have used for decades. That compatibility is the primary advantage. An old lead-acid battery can be removed and replaced with a lithium unit without modifying existing wiring.

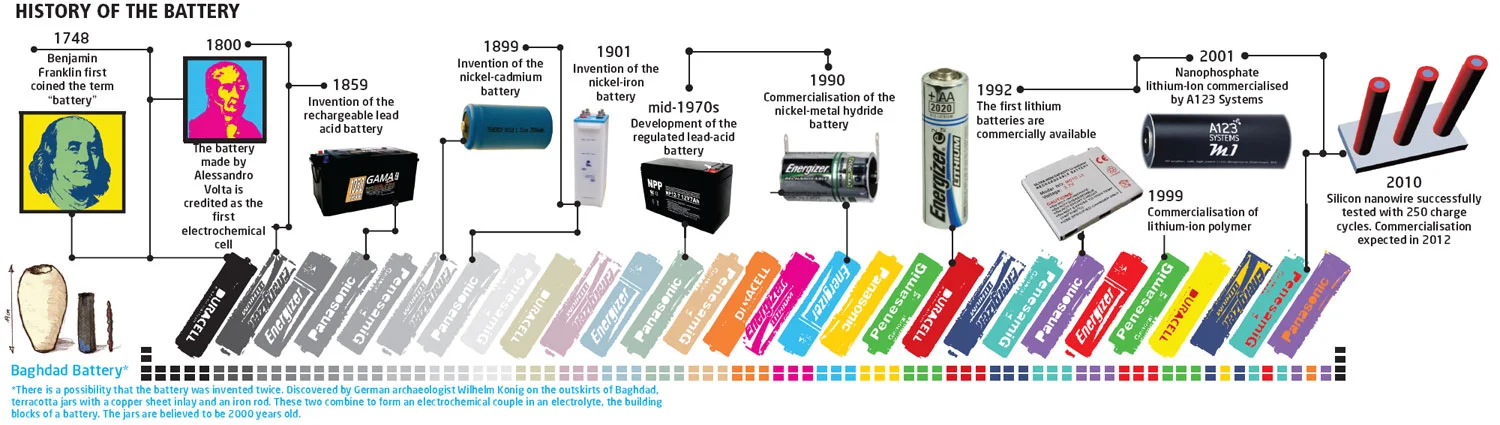

The chemistry operates on an entirely different principle from lead-acid. Lead-acid technology has not fundamentally changed since Gaston Planté developed it in 1859. Lead plates sit in sulfuric acid, and that remains the extent of the chemistry. Lithium batteries use lithium ions that shuttle back and forth between electrodes, and the energy density this achieves is something lead-acid will never match. Chemistry imposes a hard ceiling that no amount of engineering can circumvent.

The 12-volt standard itself is somewhat arbitrary—it dates back to the early automotive industry's decision to use 6-cell lead-acid batteries (2V per cell × 6 = 12V). The entire RV, marine, and off-grid industry built around this number. Lithium manufacturers had to reverse-engineer their cell configurations to match a voltage that was never designed with lithium in mind. Four LiFePO₄ cells at 3.2V each produce 12.8V—close enough to work, but the slight voltage difference actually causes compatibility issues with some older charge controllers.

Cell Chemistry: The Foundation of Performance

The marketing departments of battery companies have done considerable damage to consumer understanding here. LiFePO₄, NMC, LTO—these get thrown around as if they were interchangeable labels rather than fundamentally different electrochemical systems with distinct performance envelopes.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO₄)

Most 12-volt lithium batteries on the market use lithium iron phosphate cells. Each cell runs at 3.2 volts nominal. String four together and the result is 12.8 volts—which is why spec sheets often say 12.8V instead of rounding to 12V. Fully charged, the voltage reaches 14.4 to 14.6 volts. When voltage drops to around 10 volts, recharging becomes necessary. Going lower triggers the BMS to cut output and prevent damage.

The crystal structure is called olivine. The phosphate bonds hold oxygen atoms tight enough that thermal runaway cannot occur. Other lithium chemistries—those in phones, in Teslas—have layered oxide cathodes that can release oxygen when temperatures rise, leading to fires. LiFePO₄ cells remain stable under the same conditions.

Covalent phosphorus-oxygen bonds are harder to break than the ionic bonds in layered oxides. The bond dissociation energy for P-O sits around 597 kJ/mol compared to roughly 360-400 kJ/mol for the metal-oxygen bonds in layered oxides. This difference explains the thermal stability gap between chemistries.

A LiFePO₄ cell stores approximately 160 Wh/kg according to CATL's 2023 specifications, while NMC cells achieve 265 Wh/kg or higher in recent formulations. For applications where every gram matters—phones, laptops, electric cars—that difference is significant. For a 12V house battery in an RV, the weight penalty matters far less than the safety margin.

Iron and phosphorus are also inexpensive and globally available, which matters more than is often recognized. Cobalt supply chains are problematic—most cobalt originates from the DRC, with associated geopolitical and ethical complications. The artisanal mining operations there have been documented extensively by Amnesty International and others, though the battery industry prefers not to discuss this aspect of the supply chain. LiFePO₄ sidesteps this entirely. As global battery demand scales to terawatt-hours annually, material availability becomes a strategic concern, not merely a cost issue.

LiFePO₄'s voltage curve is also remarkably flat. The cell maintains 3.2-3.3V for roughly 80% of its discharge cycle before declining. Inverters see consistent voltage almost until the battery is depleted, whereas lead-acid voltage sags continuously from full to empty, affecting everything connected to it—lights dim, motors slow down, sensitive electronics malfunction.

Ternary Lithium (NMC/NCM)

These use nickel, manganese, and cobalt in the cathode, with various ratios designated by numbers—NMC 811 means 8 parts nickel, 1 part manganese, 1 part cobalt. Higher nickel content means higher energy density but lower thermal stability.

NMC cells run at 3.7V nominal, so three in series produces 11.1V (too low) and four produces 14.8V (functional, but the voltage curve differs enough to cause charging complications). "12V" NMC packs exist but are far less common than LiFePO₄ for stationary applications.

NMC typically delivers 1,500 cycles at 80% depth of discharge based on Samsung SDI cell data, while LiFePO₄ delivers 4,000 cycles under equivalent conditions according to BYD's published specifications. For RVs, boats, and solar storage, LiFePO₄ represents the more practical choice.

Lithium Titanate (LTO)

LTO cells handle extreme charging rates—current can be applied at 10C or higher without damage. They operate at temperatures down to -30°C where other lithium chemistries become sluggish or dangerous. Energy density sits around 70 Wh/kg, and costs remain high. LTO makes sense for grid frequency regulation or buses that charge at every stop.

Lithium vs Lead-Acid

Weight is the obvious factor. Storing one kilowatt-hour in lead-acid requires approximately 25 kg depending on the battery type. Lithium accomplishes the same in approximately 9 kg. Lead is inherently heavy—there is no engineering solution to the periodic table. Lead-acid batteries require excess plate material and electrolyte to support the dissolution-precipitation reactions that occur during cycling. This overhead cannot be eliminated without fundamentally altering the chemistry.

Energy density follows from that constraint. Lead-acid manages 35-40 Wh/kg for typical deep-cycle units. Lithium achieves 160-200 Wh/kg depending on chemistry. Four to five times better. But these numbers do not tell the complete story, because not all of a lead-acid battery's rated capacity is actually usable.

Charge efficiency. Lead-acid wastes approximately 22% of input energy as heat during the charge cycle—this varies with charge rate and temperature, but Peukert effect studies consistently show losses in the 18-25% range. Lithium wastes 3-4% based on round-trip efficiency measurements. For solar panel systems, that difference accumulates quickly. Lead-acid discards roughly a quarter of solar harvest.

In practical terms: with a 400W solar array and a need to store 200Ah per day, lithium's high efficiency means generating only slightly more than 200Ah worth of solar. With lead-acid's lower efficiency, substantially more generation is required—a larger solar array for the same usable storage, or equivalently, less usable capacity from the same panels.

RV owners focus on weight because of cargo limits. The Gross Vehicle Weight Rating is a hard ceiling, legally enforced, and many rigs approach it even before adding cargo. A 100Ah lithium battery weighs approximately 13 kg based on Battle Born and Renogy specifications. The lead-acid equivalent exceeds 30 kg. That frees 17 kg or more for water, food, or other cargo.

Packaging efficiency adds another dimension to the comparison. Lithium batteries are rectangular prisms with minimal wasted space. Lead-acid batteries, especially flooded ones, require room above the plates for electrolyte, room for terminal posts, and thick cases to contain the acid.

BMS: The Intelligence Layer

Every lithium battery contains a Battery Management System. It is a circuit board that monitors cell voltages, balances charge between cells, watches temperature, and cuts output if problems arise. The BMS transforms a collection of cells into a functional battery—without it, the result would be dangerous and short-lived.

The BMS handles overcharge protection, overdischarge protection, and short circuit protection automatically. Lead-acid requires checking electrolyte levels, performing equalization charges, and cleaning corroded terminals. Lithium operates without such intervention.

BMS quality varies enormously across the market, and this is where inexpensive batteries cut corners. A quality BMS monitors each cell individually—that means four monitoring points for a 12V LiFePO₄ pack. It tracks not just voltage but rate of voltage change, which helps detect failing cells before they cause problems. Temperature sensors should be positioned on the cells themselves, not merely floating in the case air. Balancing circuits should be active, meaning they can transfer energy between cells, not just passive (which can only bleed off excess from high cells as heat).

Short circuit response occurs in microseconds, far faster than any fuse. The BMS uses MOSFETs as high-speed switches that can break the circuit in under 100 microseconds—before conductors have time to heat significantly. Mechanical fuses are much slower for the same current level.

Some budget battery manufacturers use the same BMS design regardless of battery capacity. A BMS rated for 100A continuous might be installed in a 300Ah battery, creating a bottleneck when high-draw appliances operate. The BMS specs should be checked independently of the cell specs.

The nail penetration test illustrates this stability: driving a nail through a fully charged LiFePO₄ cell produces no fire, no explosion, perhaps slight warmth. The same test on an NMC cell explains why phone batteries occasionally appear in news reports. Combined with LiFePO₄'s inherent stability—these cells have passed nail penetration tests, crush tests, and deliberate short circuits—the result is something safe enough to install inside living spaces.

Lead-acid batteries produce hydrogen gas during charging, especially during overcharge and equalization. Installation in an unventilated space creates an explosion hazard. LiFePO₄ is completely sealed, produces no gas under normal operation, and the BMS prevents the overcharge conditions that might cause gassing.

Charging Requirements and Common Mistakes

Using a lead-acid charger on a lithium battery will damage it. The two chemistries require fundamentally incompatible charging profiles, and the fact that a lithium battery appears to charge normally on a lead-acid charger makes this mistake more dangerous, not less.

Lead-acid chargers use a three-stage process—bulk, absorption, float. The float stage trickle-charges continuously at around 13.6V to compensate for self-discharge and maintain full capacity. Without float charging, a lead-acid battery self-discharges and sulfates.

Lithium batteries do not need float charging. They self-discharge so slowly that float is unnecessary—and continuous voltage at 13.6V keeps lithium cells in a slightly overcharged state that accelerates electrolyte decomposition. The SEI layer (the thin film that forms on the anode surface during initial cycling) slowly grows thicker, consuming lithium and reducing capacity. A battery expected to last 10 years might fail in 5.

Lithium chargers use constant-current, constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging. They push current until voltage hits the target (usually 14.6V for a 4-cell pack), then allow current to taper until it approaches zero. Then they stop. No float stage. Some chargers offer a "storage mode" that charges to 50-60% for long-term storage, which further extends life.

Lithium also charges rapidly. A 100Ah battery might fully charge in 4 hours at reasonable C-rates. Lead-acid takes 10 hours or more for the same capacity because the absorption phase is slow—fighting the increasing resistance of nearly-full plates.

Partial-charge tolerance differs substantially between chemistries. Lead-acid batteries need to reach full charge regularly; leaving them partially charged promotes sulfation. Lithium has no such requirement. Cycling between 20% and 80% indefinitely causes no damage—in fact, this "middle zone" cycling actually extends lifespan by reducing stress at the voltage extremes.

Using the wrong charger produces, at best, incomplete charging—the lead-acid charger's voltage profile does not match what lithium cells require, leaving capacity unused. At worst, it causes swelling cells, electrolyte decomposition, and potential safety hazards.

Some older charge controllers, especially PWM solar controllers, have hardcoded lead-acid voltage setpoints that cannot be changed. These will overcharge lithium batteries daily, causing gradual damage. MPPT controllers with adjustable setpoints work properly, but require correct programming. The forums are full of posts from people who installed lithium batteries with default charge controller settings and then complained about premature failure—a predictable outcome that the battery manufacturer gets blamed for.

Depth of Discharge

Lead-acid batteries perform poorly with deep discharge. Going past 50% causes lead sulfate crystals to grow in forms that resist conversion back during charging—a process called sulfation, and the reason manufacturers specify keeping lead-acid above 50% charge. Ignoring this guidance leads to battery failure within a year.

During discharge, lead and lead dioxide at the electrodes convert to lead sulfate. During charging, the reaction reverses. But if lead sulfate crystals remain too long, or if they grow too large, they undergo a phase change into a more stable crystalline form that will not easily dissolve back into the electrolyte. Permanent capacity loss follows, proportional to both depth and duration of discharge.

Desulfation chargers are pulse-charging devices marketed as capable of reviving sulfated batteries. The scientific support for these claims is weak. Some users report modest improvements; controlled studies show minimal effect on severely sulfated cells. The pulse frequencies and amplitudes required to mechanically disrupt crystalline lead sulfate would likely damage the plates themselves. These devices probably work best as preventative maintenance on mildly sulfated batteries rather than resurrection tools for dead ones.

LiFePO₄ handles 80-90% depth of discharge without issue. Some manufacturers claim 100%, though regular operation at absolute zero warrants caution—the BMS cutoff voltage usually leaves a small margin regardless. The intercalation mechanism does not produce the same irreversible byproducts.

When lithium ions move between electrodes, they slot into spaces in the crystal lattice and then leave again. The electrode materials expand and contract slightly, but no new chemical compounds form.

| Specification | Lead-Acid | LiFePO₄ |

|---|---|---|

| Usable Capacity (100Ah rated) | 50Ah | ~85Ah |

| Recommended DoD | 50% | 80-90% |

| Sulfation Risk | High below 50% | None |

| Partial Charge Tolerance | Poor | Excellent |

A 100Ah lead-acid battery provides 50Ah of actually usable capacity for reasonable longevity. A 100Ah LiFePO₄ provides approximately 85Ah with conservative management.

Two 200Ah lead-acid batteries provide 200Ah usable (50% × 400Ah). Replacing them with a single 200Ah LiFePO₄ pack yields approximately 170Ah usable—similar capacity—while cutting weight significantly and freeing half the battery compartment space.

How Long They Last

LiFePO₄: 4,000 cycles at 80% depth of discharge represents the industry standard. Quality cells from manufacturers like CATL and EVE consistently achieve this figure, with CATL's published data showing 6,000 cycles at 70% DoD. Claims of 10,000 cycles at shallower depths appear in some marketing, supported by accelerated aging data, but field data over that timespan remains limited.

Lead-acid: 400-800 cycles under similar conditions. AGM performs better than flooded, and some premium deep-cycle lead-acid batteries approach 1,000 cycles. But replacement every 2-3 years remains typical under daily cycling.

The cycle life ratings deserve scrutiny. Manufacturers test at specific conditions—usually 25°C, controlled charge rates, specific DoD. Real-world conditions are variable. Heat degrades lithium faster; a battery in a Phoenix RV closet might experience 40°C ambient regularly. High charge rates during fast solar absorption stress both chemistries. The stated cycle ranges account for reasonable real-world variation.

One cycle per day means LiFePO₄ should last 8-10 years. Field installations confirm these figures. Off-grid telecom batteries deployed since 2016 reportedly maintain over 85% capacity retention after 2,500+ cycles.

Self-discharge rates differ substantially. Lithium loses 2-3% per month based on manufacturer specifications. Lead-acid loses 15-20% monthly. a lead-acid battery left unused over winter may be deeply discharged by spring, potentially damaged. Lithium remains near its storage state of charge.

Price Analysis

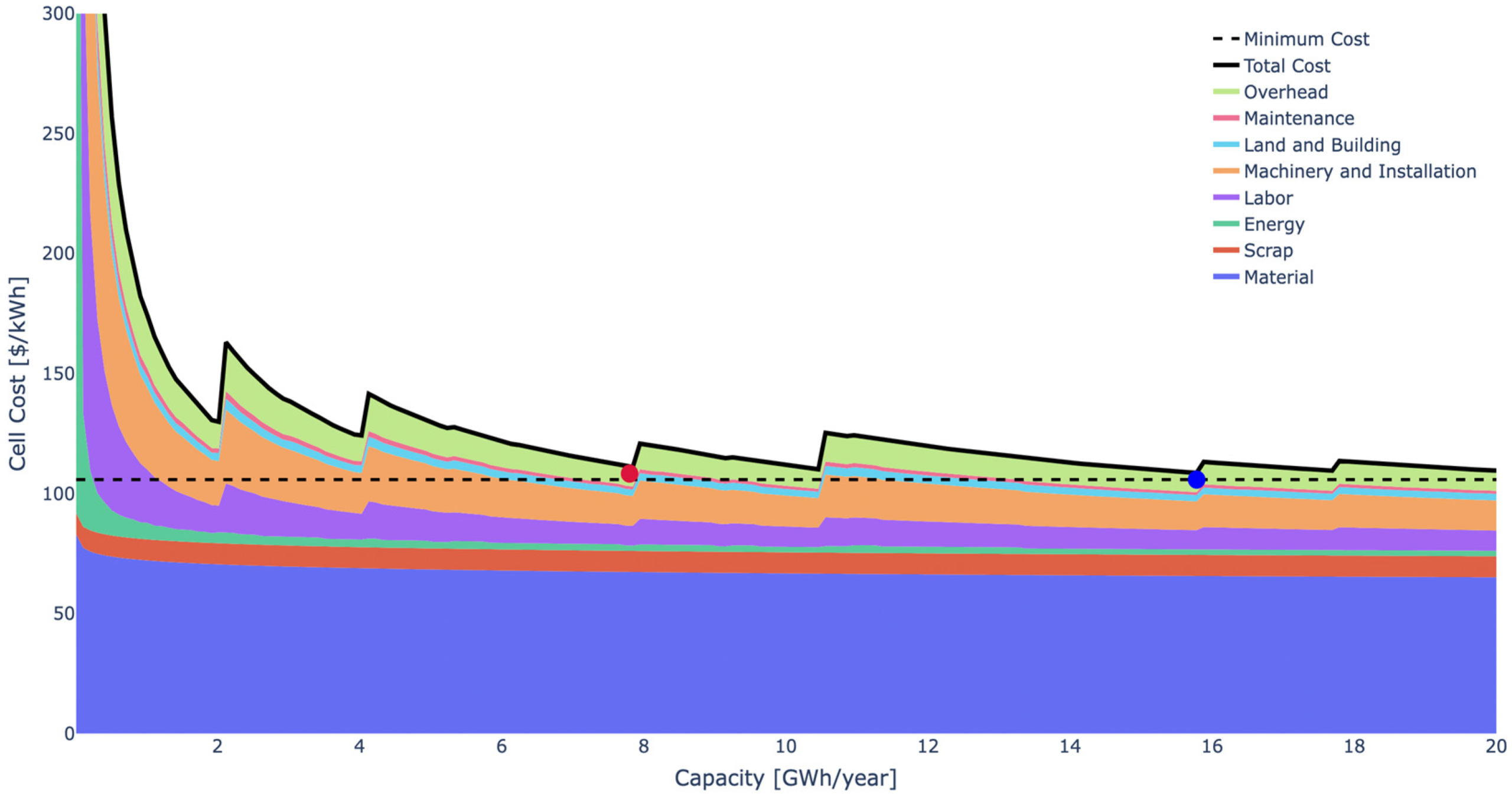

Lithium costs more upfront. A 100Ah 12V LiFePO₄ runs $200-350 depending on brand and cell quality—prices have been declining steadily since 2018. The lead-acid equivalent is $60-80 for flooded, $120-180 for AGM.

Calculations over time change the picture substantially. Lithium lasts 8-10 years with daily cycling. Lead-acid requires replacement every 2-3 years under the same use pattern. Over a decade, purchasing 3-4 lead-acid batteries becomes necessary. Meanwhile the single lithium battery continues operating. Labor and inconvenience of multiple replacements add further costs not reflected in purchase price.

Adding charging efficiency losses makes lead-acid look worse. More electricity is purchased to store less of it. Over thousands of cycles, that efficiency penalty amounts to real money—especially at higher electricity rates or with limited solar capacity.

Most use patterns reach cost parity within 3-4 years. Daily cycling reaches parity faster.

System sizing contains a hidden cost factor. Because lithium provides nearly double the usable capacity per amp-hour rated, a smaller lithium battery can match the usable capacity of a larger lead-acid bank. A 100Ah lithium replaces 200Ah of lead-acid in actual usable energy. Factoring this in, the upfront cost premium shrinks considerably.

The price trajectory also favors lithium. Cell costs have dropped dramatically over the past decade, driven by electric vehicle manufacturing scale. Lead-acid is a mature technology with limited cost reduction potential—lead will not become cheaper, and more efficient manufacturing methods are largely exhausted. Lithium costs will continue falling as production scales, while lead-acid stays roughly flat or rises with raw material prices.

The Chinese cell market complicates straightforward price comparisons. Cells direct from China cost approximately 40% of what US distributors charge. But shipping lithium batteries internationally involves regulatory complexity—hazmat fees, documentation requirements, and shipping delays. The IATA dangerous goods regulations classify lithium batteries under Section II or Section I depending on watt-hour rating, and the paperwork requirements alone deter casual importers. The domestic premium exists for valid reasons.

A tangent worth mentioning: the secondary market for lithium cells has grown substantially. Electric vehicle battery packs retired at 70-80% capacity still function adequately for stationary storage applications. Salvaged Tesla modules, Nissan Leaf packs, and similar sources provide cells at steep discounts. The technical challenges of repurposing these cells—building appropriate BMS configurations, matching degraded cells, managing different form factors—limit this approach to technically sophisticated buyers. But the economic case is compelling for those willing to invest the effort. Whether salvage cells represent a sustainable market segment or merely a transitional phenomenon while new cell prices decline remains unclear.

Capacity and Configuration Options

12-volt lithium batteries range from under 10Ah to over 300Ah.

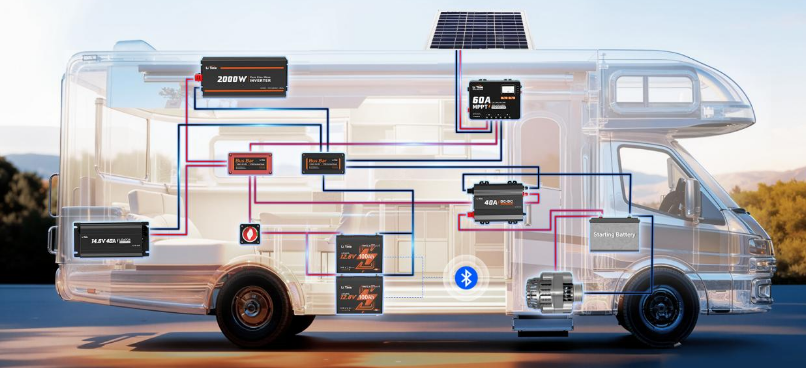

Series connections increase voltage. Two 12V batteries in series produce 24V. Four produce 48V. Higher voltage means lower current for the same power, which permits thinner wires and reduces I²R losses. A 3,000W load at 12V draws 250A, requiring massive cables for any reasonable distance. The same load at 48V draws 62.5A, manageable with much smaller wire. Solar installations are moving toward 48V for this reason, and 48V is becoming standard for new RV builds.

Parallel connections increase capacity at the same voltage. But batteries must be matched—same capacity, similar age, similar health, ideally same manufacturing batch. Mismatched parallel configurations create circulating currents as stronger batteries attempt to charge weaker ones, accelerating degradation across the entire bank. Some modern batteries have communication ports (usually CAN bus or RS485) for coordinated operation, which helps manage parallel strings by sharing state-of-charge information and balancing loads.

Paralleling batteries with different BMS designs causes problems. Even if cells are identical, BMS units with different cutoff voltages or different balancing algorithms can conflict. One BMS might cut off at 2.5V per cell while another waits until 2.0V—the first battery stops contributing while the second continues discharging, creating severe imbalance.

For large systems, a single higher-capacity battery is generally preferable to multiple smaller paralleled units, if space and budget allow.

Where These Batteries Are Used

RVs and Camping

Lithium adoption has proceeded fastest in this segment. Weight savings translate directly to range, payload capacity, and fuel efficiency. A motorhome carrying 50 kg less in batteries achieves measurably better mileage—not dramatic, but noticeable over a season of travel.

Faster charging enables complete recovery while driving. A quality alternator charging system can push substantial current into a lithium bank, replenishing 100Ah in a few hours of driving. Lead-acid cannot accept current at that rate without overheating, resulting in lower charge rates and longer charging times.

Lithium batteries function in any orientation—a fact that opens up installation options in tight RV compartments where a vertical or angled battery fits better. Lead-acid must remain upright or acid leaks.

The RV aftermarket has matured quickly. Drop-in replacements with Group 24, 27, and 31 form factors match existing battery boxes. Integrated Bluetooth monitoring allows state of charge monitoring via smartphone. Some units include built-in heating elements for cold-weather charging.

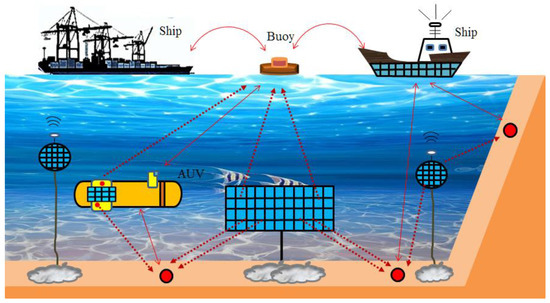

Marine Applications

Boats present unique challenges: vibration, humidity, salt air, irregular use patterns, and strong incentives to avoid sinking.

Vibration tolerance comes from the solid-state nature of lithium cells. There is no liquid sloshing around, no delicate plate grids to crack. Marine-rated lithium batteries typically include enhanced shock mounting.

Trolling motor applications benefit particularly from lithium's flat discharge curve. A lead-acid battery driving a trolling motor gradually loses voltage as it discharges—starting with full power and ending with a motor barely turning. Lithium maintains consistent voltage until the battery is nearly empty, providing reliable thrust throughout a day of use.

Weight distribution matters for boat trim. Lithium batteries weigh less, allowing positioning for optimal balance rather than placement dictated by heavy lead-acid blocks.

The marine industry has been slower to adopt lithium than the RV market, partly due to insurance concerns and ABYC certification requirements. The American Boat and Yacht Council standards for lithium installations require specific BMS features, disconnect mechanisms, and installation practices that add complexity compared to simply dropping in a lead-acid replacement. This regulatory overhead slows adoption even when the technical case for lithium is strong.

The insurance question deserves elaboration. Marine insurers have historically been conservative about new technologies, and lithium battery fires in other contexts—hoverboards, e-bikes, cargo ships carrying lithium batteries—have not helped the perception issue. Some insurers require specific certifications, professional installation documentation, or charge premiums for lithium-equipped vessels. The situation varies significantly by insurer and region. European insurers have generally adapted faster than American ones, possibly due to different regulatory frameworks or simply different institutional cultures around technological change. None of this reflects the actual risk profile of properly installed LiFePO₄ systems, which is arguably lower than lead-acid given the absence of hydrogen gassing.

Other Applications

Golf carts benefit from weight reduction, increased range, and elimination of battery watering. Solar installations value efficiency and cycle life. Scooters require manageable weight for practical use.

UPS applications present an interesting case. The low self-discharge of lithium means a UPS battery remains ready after months of standby—lead-acid UPS batteries often fail precisely when needed because gradual self-discharge was not compensated by adequate float charging. Data centers have begun transitioning to lithium UPS systems, though the higher upfront cost slows adoption in cost-sensitive applications.

Maintenance

LiFePO₄ batteries eliminate the maintenance rituals that lead-acid demands.

Lead-acid maintenance is not optional—it is essential for reasonable lifespan. Flooded batteries require periodic electrolyte level checks and distilled water additions. Equalization charging (deliberate overcharging to reverse stratification) must occur monthly or capacity loss occurs. Terminal corrosion demands cleaning. Specific gravity measurements assess state of health and cell balance.

Neglecting any of these accelerates degradation. Overfilling electrolyte causes acid overflow during charging. Underfilling causes plates to dry out, resulting in permanent damage. Skipping equalization allows electrolyte stratification—acid concentration increases at the bottom, destroying lower plate sections. Missing corroded terminals increases resistance, causing charging problems and voltage drops.

Lead-acid batteries often fail prematurely because "maintenance" consisted of occasional visual inspection rather than actually performing the required tasks. Most users lack the equipment or discipline to keep lead-acid batteries healthy.

Lithium requires none of this. Installation involves mounting the battery, connecting terminals, configuring monitoring systems, and programming charge parameters. Daily operation proceeds without intervention. Annual inspection might confirm terminal tightness and absence of physical damage—five minutes once a year.

This maintenance elimination delivers value beyond labor savings. It removes the possibility of maintenance errors—overfilling, neglecting equalization, ignoring corrosion.

Cold Weather Considerations

Temperature affects all batteries, but the specifics differ between chemistries in important ways.

Lead-acid performance drops in cold—internal resistance increases, available capacity decreases—but charging and discharging a cold lead-acid battery causes no permanent damage. It operates poorly until it warms up.

Lithium batteries, specifically the graphite anode in most lithium chemistries, cannot safely accept charge below 0°C (32°F). Charging a cold lithium battery causes lithium metal plating on the anode surface rather than proper intercalation. This plating is irreversible, reduces capacity, and can eventually cause internal shorts.

Most quality LiFePO₄ batteries include low-temperature charging cutoffs in the BMS—the battery refuses to charge below 0°C. The cells are protected, but an operational challenge emerges: a battery might be at 20% capacity on a cold morning, but charging cannot begin until it warms up.

Solutions exist. Some batteries include internal heating elements that warm cells before charging. Others rely on discharge self-heating—running a load warms the battery enough to enable charging. Insulated battery boxes slow heat loss during cold nights.

Discharge at cold temperatures is acceptable for lithium—no damage occurs, though available capacity drops somewhat. Available capacity might be 85% of rated capacity at -20°C versus 100% at room temperature.

Understanding this limitation matters for application selection. A lithium battery for winter camping needs cold-weather features. A battery for a boat stored in a heated garage does not.

Pre-heating cells using the BMS itself by intentionally creating a small internal resistance load—essentially using the battery's own inefficiency to generate warmth—has been discussed in technical forums. The approach works in principle but adds complexity to BMS design, and commercial implementations remain rare. Most manufacturers have opted for simpler resistive heating pads instead.

The Alaskan market provides an interesting data point. Off-grid cabins in interior Alaska experience temperatures below -40°C regularly. Early lithium adopters in these areas reported mixed results—systems with inadequate cold-weather provisions failed quickly, while properly designed installations with heating and insulation performed well. The lesson is that lithium works in extreme cold, but requires more careful system design than in temperate climates. Lead-acid, despite its other limitations, tolerates cold-weather charging without special provisions, which explains its continued popularity in extreme northern applications where system simplicity matters.