The battery aisle lies to you. Not through omission or careful phrasing, but through numbers printed right on the package that mean almost nothing once you get the thing home.

Take that 2,800 mAh rating on your Duracell AA. Technically accurate. Also basically useless. The International Electrotechnical Commission tests alkaline capacity at 25 milliamps continuous draw. Twenty-five. Your TV remote might pull that. A wall clock, maybe. Know what else does?

Stick those same cells in a digital camera and watch the magic disappear. The flash capacitor wants over 1,000 milliamps during recharge. At that load, your 2,800 mAh battery delivers maybe 700 mAh of usable capacity before voltage craters below what the camera needs. You paid for four times what you got.

The chemistry just can't keep up. Potassium hydroxide electrolyte, zinc anode slowly dissolving into zinc oxide, ion diffusion that works fine when you're sipping current but chokes completely when you're gulping it. Internal resistance spikes. Energy converts to heat instead of photographs. Sixty shots if you're lucky, then you're hunting for fresh cells.

I switched my Canon to lithium iron disulfide AAs three years ago. Same camera body. Over 500 shots per set. The Energizer Ultimate Lithiums actually have lower nominal capacity on paper, around 3,000 mAh versus some alkaline claims of 3,200. Doesn't matter. The lithium chemistry doesn't care that you're demanding 800 milliamps. It just delivers.

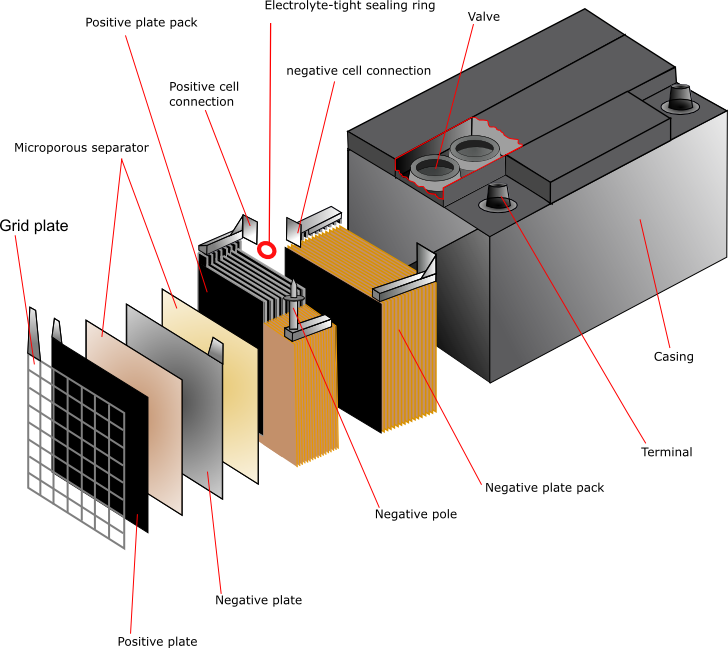

Here's the thing about alkaline cells that took me years to fully appreciate. They're destructive by nature. Not in the sense that they'll hurt you, but in what happens inside the cell during discharge.

The zinc anode doesn't just release electrons. It dissolves. Literally transforms into a different compound. Zinc oxide accumulates, clogs the porous structure designed to maximize surface area, and progressively strangles the reaction. You start with this carefully engineered high-surface-area zinc matrix, and by the time you're done, it's a dense mass of oxide that can't participate in electrochemistry anymore.

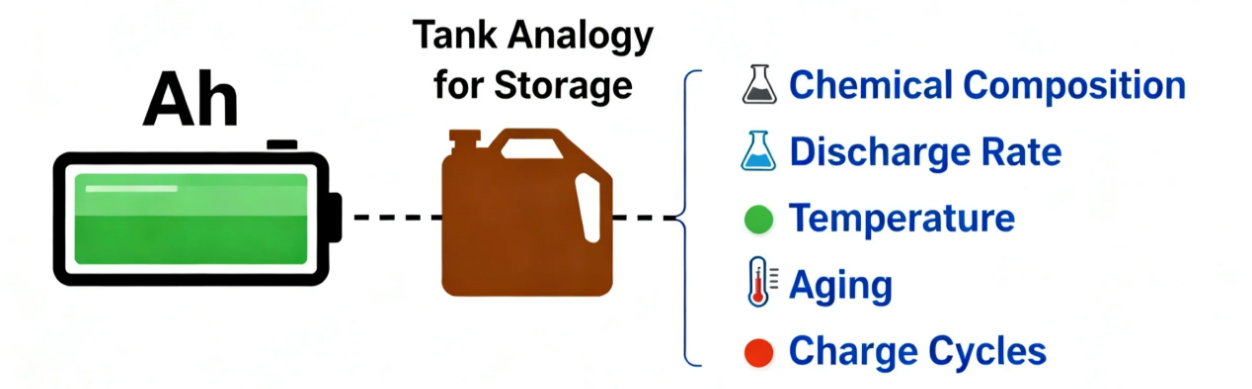

The internal chemistry of batteries determines their real-world performance far more than capacity ratings suggest

The cathode side has its own problems. Manganese dioxide accepts protons during discharge, and those protons expanding the crystal lattice until particles fragment and electronic pathways break down. The mechanical stress accumulates. Shallow discharges preserve some integrity. Deep discharges produce irreversible structural damage that no amount of resting will fix.

There's no going back. The chemistry is a one-way street.

That "recovery" you notice after letting tired alkalines rest for a few hours? That's just concentration gradients dissipating. Some ionic mobility returns. But the consumed electrode material stays consumed. The zinc that became zinc oxide isn't turning back into zinc. The fractured manganese dioxide particles aren't reassembling themselves.

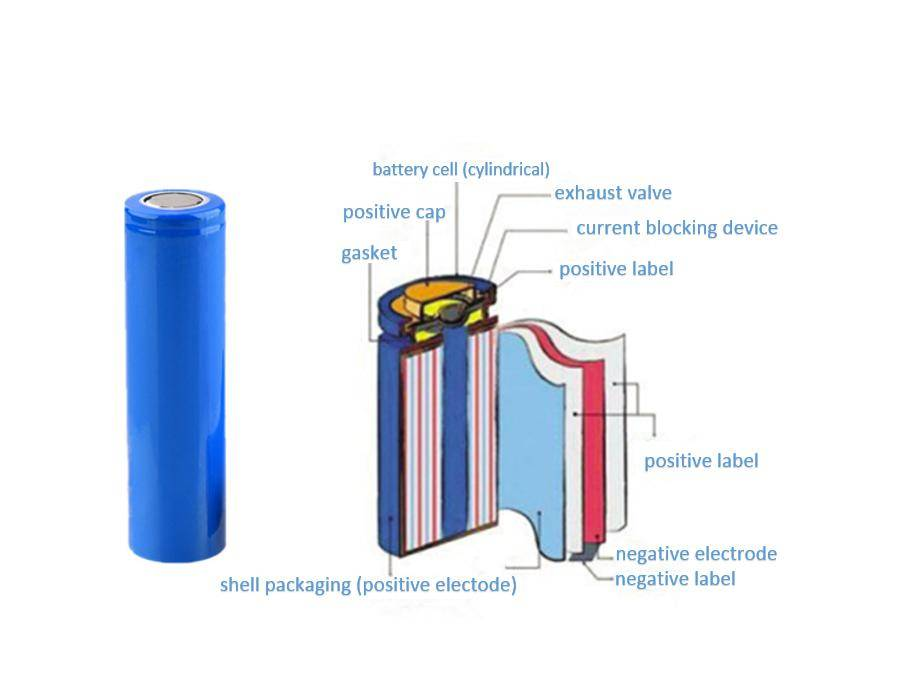

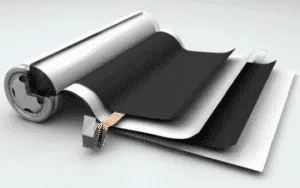

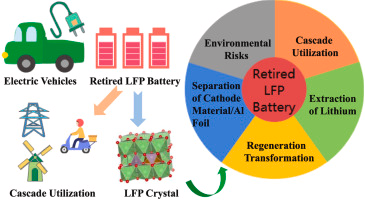

Lithium-ion works on entirely different principles. Intercalation instead of conversion. Lithium ions shuttle between graphite anode and metal oxide cathode, slipping between crystal layers without destroying anything. The carbon-carbon bonds in the graphite stay intact. The cathode framework remains. You're renting space in a crystal structure, not demolishing it.

This is why lithium-ion batteries can handle hundreds of charge cycles while alkaline batteries are strictly one-and-done. The fundamental reaction preserves the electrode materials rather than consuming them.

The voltage advantage compounds everything else. Alkaline's zinc-manganese dioxide reaction tops out at 1.5 volts because thermodynamics says so. The Gibbs free energy of the overall cell reaction sets a ceiling that no amount of engineering cleverness can breach. Lithium couples hit 3.6 to 3.7 volts nominal. Energy equals voltage times capacity. When you triple the voltage while maintaining comparable specific capacity, you get proportional energy density improvements. The math is straightforward, and it favors lithium by a wide margin.

The electrolyte differences matter too, though people rarely think about them. Alkaline batteries use potassium hydroxide, typically 35 to 37 percent KOH by weight, dissolved in water. That concentration represents a careful optimization with little room for improvement. Lower concentrations improve ionic conductivity but reduce the thermodynamic driving force for zinc dissolution. Higher concentrations increase viscosity and reduce the water activity needed for the cathode reaction. Engineers squeezed what they could out of this chemistry decades ago.

Lithium batteries use organic solvents. Lithium hexafluorophosphate dissolved in ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate. These remain liquid at temperatures that would freeze aqueous solutions solid. They're also not corrosive in the way potassium hydroxide is, which matters enormously for long-term storage. More on that later.

What really converted me wasn't the capacity numbers or the electrochemistry lectures. It was watching the voltage curves on an oscilloscope.

Fresh alkaline starts around 1.6 volts open-circuit, drops to 1.5 volts the moment you connect a load, then just slides. 1.4 volts. 1.3 volts. 1.2 volts. Your flashlight dims continuously throughout this decline. The motor in your kid's toy slows down in a way that's perceptible if you're paying attention. Electronic circuits designed for 1.5 volt operation start exhibiting marginal behavior as voltage drops toward 1.2 volts, even though the battery still has theoretical capacity remaining. Capacity you can't access because your device has already given up.

Lithium iron disulfide cells behave completely differently. An Energizer Ultimate Lithium holds 1.5 volts under load from 10 percent discharged all the way to 90 percent discharged. The voltage curve is essentially flat across that entire range. Then it falls off a cliff. The SureFire flashlight community documented this obsessively back in the early 2000s when they were testing every battery chemistry they could get their hands on. Full brightness for four hours, then nothing. No warning, no gradual decline, just done.

People complain about this sudden death characteristic. They're used to alkaline's gentle fade giving them warning that replacement time approaches. But think about what you're actually getting with each approach. Would you rather have two hours of adequate light followed by three hours of increasingly useless dimness? Or four hours of full brightness followed by immediate shutoff? When the power's out and I'm trying to find the breaker box at 2 AM, I know which one I want.

The "no low battery warning" complaint reflects habit rather than rational evaluation of which discharge profile actually serves user needs better. Most devices designed in the last decade include their own battery monitoring anyway, making the gradual alkaline decline redundant as a warning mechanism.

Cold weather performance is where alkaline batteries go from merely disappointing to genuinely embarrassing.

That potassium hydroxide electrolyte I mentioned earlier has a significant weakness. It freezes. The exact freezing point depends on concentration, but you start seeing serious problems well above the freezing point as ionic mobility decreases with temperature.

At 0 degrees Celsius you're getting half your room-temperature capacity. The ions can still move, but they're sluggish. Internal resistance climbs. Voltage sags under load.

At negative 10 Celsius, you're down to maybe 25 percent capacity. The electrolyte is approaching the viscosity of honey. Discharge rates that would be trivial at room temperature become problematic.

At negative 20 Celsius, most alkaline batteries are essentially decorative. The electrolyte has either frozen solid or become so viscous that ion transport effectively stops. You can warm the battery up and recover function, but that's not helpful when you need it to work right now in the cold.

Extreme cold temperatures reveal the fundamental limitations of alkaline battery chemistry

I learned this the hard way on a January camping trip in the Boundary Waters along the Minnesota-Ontario border. Headlamp died the first night. Fresh Duracells installed that morning. Temperature was around negative 15 Celsius. The batteries weren't dead. They were just too cold to deliver current at the rate my headlamp demanded.

Lithium primary cells laugh at these temperatures. Still delivering 80 percent or more of rated capacity at negative 20 Celsius. Still functional at negative 40 where the distinction between Celsius and Fahrenheit scales disappears and everything is just brutally, dangerously cold.

There's a reason Antarctic research stations and Alaskan sled dog racing teams switched to lithium decades ago. There's a reason trail cameras deployed in northern Minnesota eat through alkalines every January while identical cameras running lithium keep capturing deer all winter. There's a reason avalanche transceivers, the devices that help rescuers find you after you're buried in snow, universally specify lithium batteries. When equipment failure means death, you don't mess around with chemistry that might not work.

Remote oil field operations in northern Alberta and Saskatchewan mandate lithium cells for all critical equipment now. The maintenance crews learned through expensive experience that alkaline-powered devices become unreliable precisely when conditions are worst and help is furthest away.

The performance gap in cold weather isn't marginal. It's not a matter of slightly reduced runtime that you can compensate for by carrying extra batteries. It's the difference between equipment that works and equipment that doesn't. Between communication devices that function when you need to call for help and ones that sit there with full-looking battery indicators and zero output current.

Now I need to talk about the thing that really makes me angry. The thing nobody thinks about when they're standing in the battery aisle comparing prices. The thing that has probably cost consumers more money in destroyed equipment than all the batteries themselves were ever worth.

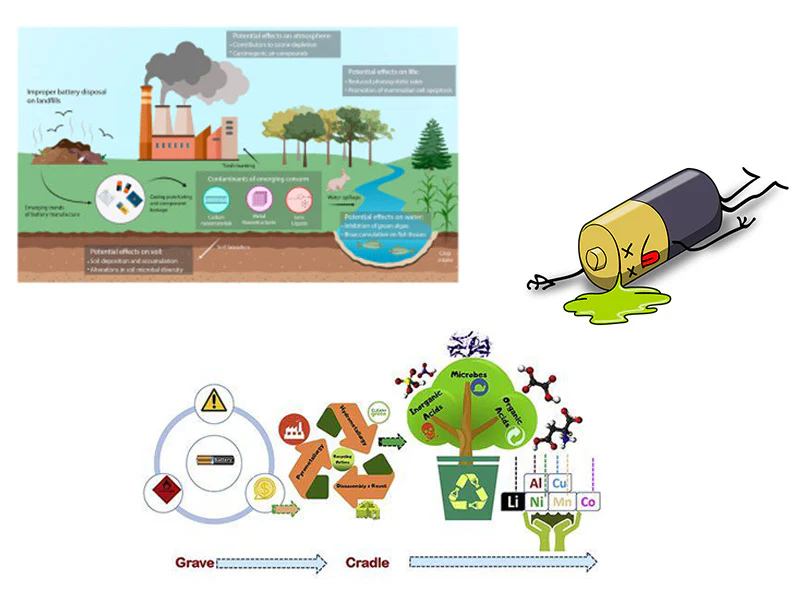

Alkaline batteries leak.

Not occasionally. Not as rare manufacturing defects. Routinely. Predictably. As a natural consequence of their chemistry and construction.

Open that junk drawer in your kitchen. The one with the flashlight you forgot about, the old Game Boy, the TV remote from three apartments ago. Look at the batteries. I'll wait.

White crystalline growths consuming the contacts. Corroded springs that used to be shiny steel. That acrid chemical smell that hits you when you get close.

The potassium hydroxide electrolyte escapes containment through aging seals, migrates along circuit traces, and destroys everything it touches. It doesn't stay confined to the battery compartment. It creeps. It wicks along wires. It penetrates foam padding and travels surprising distances from the original leak site, sometimes appearing centimeters away from where the battery actually sits.

Battery leakage has destroyed countless electronic devices, often long after the batteries were forgotten

The failure mechanism is insidious and worth understanding if you want to minimize your losses.

Primary seal failure occurs when polymer gaskets separating the anode and cathode compartments degrade through oxidation, plasticizer migration, and mechanical stress from internal gas generation. These gaskets are designed to last for years under normal conditions, but "normal conditions" assumes the battery gets used and replaced within a reasonable timeframe.

Here's what happens during over-discharge. When you drain an alkaline battery past its useful capacity, the zinc anode keeps corroding even after the manganese dioxide cathode has exhausted its ability to accept electrons through the external circuit. This continued zinc dissolution produces hydrogen gas. The hydrogen accumulates inside the sealed cell, building pressure against seals designed for ambient pressure operation.

Sometimes the cell vents this pressure through designed weak points. Sometimes it doesn't. Sometimes the pressure finds its own path out, usually wherever the seal is weakest. And wherever electrolyte escapes, damage follows.

Secondary leakage pathways develop at the crimp seal joining the cell can to the bottom cap. Manufacturing variations in crimp depth and uniformity create localized stress concentrations. Electrolyte can wick through microscopic gaps that wouldn't be visible under normal inspection but provide enough of a pathway for the hydroxide to migrate.

High humidity storage accelerates everything. Potassium hydroxide is hygroscopic. It absorbs atmospheric moisture through any opening in the seal, even microscopic ones. This absorbed water increases electrolyte volume and reduces viscosity, which enhances migration through marginal seals. Batteries stored in damp basements or humid garages fail faster and leak more extensively than ones stored in climate-controlled spaces.

The white crystalline crud appearing outside leaked cells consists of potassium carbonate, formed when the escaped potassium hydroxide reacts with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This conversion is actually somewhat helpful because potassium carbonate is less aggressively alkaline than the hydroxide. But the neutralization happens too slowly to prevent damage. The hydroxide that reaches copper circuit traces oxidizes them within hours. Tin-lead solder joints dissolve through alkaline attack over subsequent days. The electrolyte penetrates beneath conformal coatings through capillary action, causing damage that remains invisible until the circuit fails.

Cleaning corroded contacts with vinegar or lemon juice sometimes restores function to simple devices. You're neutralizing the remaining alkaline residue and hoping the underlying metal survived. Sometimes it works. But damage to actual circuit boards, corroded IC leads, and crystalline deposits beneath surface-mount components proves permanent. By the time you see visible damage, the invisible damage is usually worse.

Vintage electronics collector forums are full of this grief. Game Boy from 1989 won't power on anymore. Battery leak damage. Original Xbox controller has drift issues. Corroded contacts from Duracells that sat in there for three years between uses. Grandma's old digital camera that nobody can find pictures on because the battery compartment corrosion spread to the memory card interface. The pattern repeats across forty years of consumer electronics.

Repair technicians who specialize in retro gaming equipment report that alkaline leakage is the single most common failure mode they encounter. More than worn buttons. More than failed capacitors. More than any other cause. Batteries that were supposed to power these devices instead destroyed them.

Lithium batteries essentially don't have this problem. The organic electrolytes remain contained within properly manufactured cells. When containment failure does occur, which is rare, there's no creeping corrosion spreading centimeters from the leak site. No crystalline deposits consuming contacts. No wicking along wires to attack distant components.

I've pulled 15-year-old lithium AAs out of emergency equipment and found pristine contacts underneath. I've opened devices stored with lithium batteries for over a decade and seen no evidence that batteries were ever present beyond the batteries themselves. The contrast with alkaline storage outcomes couldn't be more stark.

The economics of battery chemistry seem straightforward at first glance, and that superficial simplicity leads people astray.

Alkaline AAs cost under a dollar at Costco if you buy the big pack. Sometimes well under a dollar. Lithium primary cells run two to three dollars each. Lithium-ion rechargeables with a decent charger might set you back forty or fifty dollars for a starter kit. Looking at those numbers, alkaline seems like the obvious choice for budget-conscious consumers.

The math falls apart once you account for actual usage patterns.

Go back to the example I mentioned earlier. Sixty shots on alkaline versus over 500 on lithium. That expensive lithium battery costs roughly one-fifth as much per photograph as the cheap alkaline alternative. The higher purchase price gets amortized across so many more uses that the per-use cost inverts dramatically.

Xbox and PlayStation controller users report similar ratios. Three weeks on alkaline during regular gaming sessions. Three months on lithium. The gamer who buys cheap alkaline batteries four times as often isn't saving money. They're spending more while also experiencing more interruptions when batteries die mid-session.

High-output flashlights show the same pattern, often more dramatically. The serious flashlight enthusiasts who test these things systematically have documented cases where lithium batteries deliver eight to ten times the runtime of alkaline in high-drain modes. Not because the lithium cells have eight times the capacity on paper, but because alkaline capacity ratings become fictional at the current draws these lights demand.

The true economics of battery choice extend far beyond the price tag on the package

The fundamental problem is that alkaline cost advantage exists only in applications where battery choice barely matters.

Wall clocks drawing microamps don't stress alkaline chemistry. They'll run for years on either battery type, so you might as well buy cheap. Remote controls used a few times per day for channel surfing fall into the same category. Wireless doorbells waiting for visitors who rarely come. Battery-powered wall thermometers. Simple kitchen timers.

These applications share common characteristics. Current draw under 100 milliamps, usually well under. Infrequent use measured in minutes per day at most. Room temperature operation. Tolerance for gradual voltage decline. No catastrophic consequence if the battery dies unexpectedly.

Once you step outside that narrow zone, the calculus shifts toward lithium. And modern devices increasingly step outside that zone. Wireless gaming controllers. Bluetooth headphones. GPS units. Trail cameras. Digital cameras. Smart home sensors. Portable LED work lights. Basically anything with a wireless radio, a display, a motor, or an LED bright enough to be useful.

Lithium-ion rechargeable economics prove even more favorable for regular-use applications. A set of Panasonic Eneloop Pro batteries rated for 500 charge cycles at 2,500 mAh per cell replaces 500 sets of disposable batteries over its service life. Even being conservative about the comparison, assuming you'd need four rechargeable sets to cover the discharge capacity of 500 disposable sets due to the slightly lower capacity per charge, you're still replacing roughly 125 purchases with one purchase. The cumulative retail cost of those disposables would approach several hundred dollars. The rechargeable system pays for itself within months of regular use.

The rechargeable option does require a charger and some logistical overhead. You need to remember to charge batteries after use. You need to have a spare set available while the primary set charges. For some people in some applications, that overhead isn't worth it. Fair enough. But the economic case for rechargeables in high-use applications is overwhelming for anyone willing to handle the minor inconvenience.

Environmental considerations add another dimension to the comparison, though I find environmental arguments less compelling than the pure self-interest case.

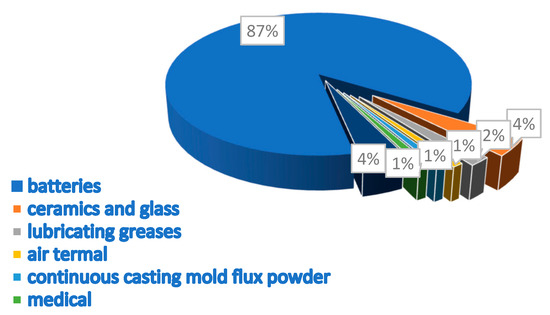

Alkaline batteries technically qualify for standard municipal waste disposal following mercury elimination from formulations in the 1990s. You can legally throw them in the trash in most jurisdictions. But the single-use nature generates enormous volumes of waste. The EPA estimates that Americans discard around three billion dry cell batteries annually, with alkaline chemistry comprising the vast majority of that total. Three billion batteries per year, every year, going into landfills.

The zinc and manganese in alkaline batteries aren't particularly toxic compared to older battery chemistries. The environmental concern is more about resource consumption and landfill volume than acute toxicity. But it's still a lot of material being used once and discarded.

Lithium-ion batteries require specialized recycling due to thermal runaway risks. You can't just throw them in the trash because damaged cells can ignite spontaneously. This creates some logistical friction. You need to find a recycling drop-off point, which might be at a big-box electronics retailer or a municipal hazardous waste facility depending on where you live. The infrastructure for lithium battery recycling remains uneven, with collection programs varying widely by region.

On the positive side, lithium battery recycling actually recovers valuable materials. Modern recycling processes can recover over 90 percent of constituent materials including cobalt, nickel, and lithium carbonate. These recovered materials have real economic value, which helps support the recycling infrastructure.

A single lithium-ion cell replacing 500 alkaline cells over its service life represents substantial waste reduction regardless of how the recycling math works out. Five hundred batteries manufactured, packaged, transported, sold, used once, and discarded. Versus one battery manufactured, packaged, transported, sold, used 500 times, and then recycled with material recovery. The environmental case for rechargeables seems clear even though I think the economic and performance cases are more likely to actually change behavior.

The environmental impact of battery choice compounds over billions of units disposed annually

So why does anyone still buy alkaline batteries? Why does the battery aisle at every store dedicate most of its shelf space to a technology that delivers a fraction of its rated performance in real-world use, damages equipment through leakage, fails in cold weather, and costs more per use than alternatives in most applications?

Habit accounts for a lot of it. Alkaline batteries have been the default for decades. Parents bought them, so their children buy them. The brand names are familiar. The packaging is reassuring. Buying Duracell or Energizer alkaline feels like buying the standard, safe, normal choice.

Upfront price matters to people more than it should. We're not very good at calculating lifetime costs while standing in an aisle comparing packages. The alkaline batteries cost a dollar. The lithium batteries cost three dollars. Our brains pattern-match to "alkaline is cheaper" even though the per-use math often runs the opposite direction. Behavioral economists have documented this bias extensively in other domains. Batteries are just another example.

The leakage damage is hidden and delayed. When your flashlight stops working three years from now because battery corrosion destroyed the contacts, you won't connect that failure to the purchasing decision you made today. The feedback loop is too long and too noisy for people to learn from experience. Every instance of alkaline leak damage gets attributed to bad luck or defective batteries or cheap equipment, not to a predictable consequence of the chemistry involved.

Marketing plays a role too. Alkaline battery manufacturers have spent decades building brand associations with reliability and performance. The advertising shows batteries powering demanding applications, creating an impression that doesn't match electrochemical reality. Most consumers have no reason to question these impressions because they lack the technical background to evaluate battery chemistry claims and they don't encounter head-to-head comparisons that would reveal the performance gaps.

Equipment manufacturers share some blame. Many devices still ship with alkaline batteries included, reinforcing the impression that alkaline is the appropriate choice. Instruction manuals often specify "AA alkaline batteries" without mentioning alternatives or explaining tradeoffs. This isn't necessarily malicious. It's just path dependence. Alkaline has been the default for so long that specifying it requires no thought.

I should acknowledge that there are some legitimate reasons to choose alkaline in specific situations.

Some older devices incorporate voltage-sensitive components designed around alkaline's declining discharge curve. Certain camera light meters from the 1990s were calibrated to assume the predictable voltage decline of alkaline chemistry. The 1.8 volt open-circuit voltage of fresh lithium iron disulfide cells, compared to 1.6 volts for fresh alkaline, might stress components in devices engineered without adequate voltage regulation margin. This is increasingly rare as modern devices include their own voltage regulation, but it's worth checking for vintage equipment.

Low-battery indicators in many devices are calibrated for alkaline discharge curves. They measure voltage and translate that to a battery percentage based on the expected alkaline voltage-versus-capacity relationship. With lithium's flat discharge curve, these indicators provide meaningless readings. They'll show full battery until moments before exhaustion, then suddenly show empty. This isn't dangerous, but it can be inconvenient if you rely on battery indicators to know when replacement is needed.

For genuinely low-drain applications in temperature-controlled environments where you don't care about leakage risk to the device, alkaline might make sense economically. A wall clock. A basic TV remote. A battery-backup for a programmable thermostat. These applications don't stress the chemistry, and the lower upfront cost translates to actual savings over the device's life.

But that list keeps getting shorter as device capabilities increase and power demands rise. The number of applications where alkaline represents the optimal choice has been shrinking for twenty years. What remains is a narrow slice of use cases surrounded by a vast market where alkaline persists through inertia rather than merit.

The switch to lithium solved all of those problems. Equipment works when I need it. Performance matches expectations. Nothing has leaked. Per-use costs went down even though per-battery costs went up.

The battery industry perfected an impressive trick over the decades. They learned to sell laboratory specifications as if they represented real-world performance. The numbers on the package aren't technically wrong. They're measured under conditions defined by international standards. They're reproducible and verifiable. They're also almost completely disconnected from how consumers actually use batteries.

A 2,800 mAh alkaline battery that delivers 700 mAh in your actual camera isn't false advertising by legal standards. The rated capacity is real. It's just measured at 25 milliamps continuous discharge, a rate that camera will never demand. The gap between specification and experience gets absorbed by consumers as some vague sense that batteries never last as long as you'd hope. The systematic nature of the discrepancy remains invisible.

But they're tradeoffs against a technology that delivers twenty or thirty percent of its advertised capacity in high-drain applications, fails almost completely in cold weather, damages equipment through leakage at rates that should be unacceptable, and costs more per use in most applications despite lower purchase prices.