IP65 gets treated like a magic stamp. Slap it on a spec sheet, suddenly the product is "outdoor rated." Sales reps cannot explain it beyond "it's waterproof." It is not waterproof.

Two digits. First digit 6 means dust-tight: talcum powder chamber at 2kg/m³ concentration, vacuum pump pulling negative pressure for eight hours straight, any visible powder inside afterward means failure. Second digit 5 means survives water jets from a 6.3mm nozzle at 12.5 liters per minute for at least three minutes from all angles. Room temperature, fresh water, factory-new unit.

That is the entire scope of what IP65 certifies. Everything else people assume about the rating is projection, wishful thinking, or sales pitch.

Submersion

IP65 does not test submersion. At all. Ever.

The "5" sprays water at the enclosure. Spraying is not submerging. These are completely different physical challenges. A seal geometry that deflects high-velocity spray beautifully may fail within minutes under static water pressure. The spray test validates that water bouncing off the surface does not find a way in. The submersion test validates that water pressing against the surface cannot force its way through. Different physics. Different seal requirements. Different failure modes.

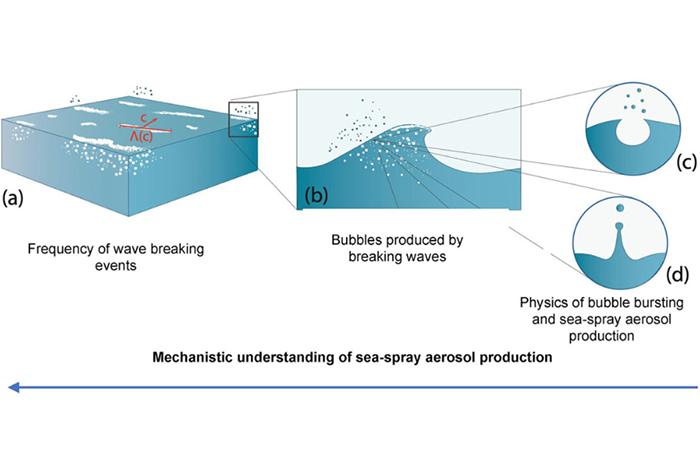

The physics of water spray versus submersion create entirely different challenges for sealing systems

Five centimeters of standing water from a clogged drain or a low spot in the yard creates hydrostatic pressure pushing inward on every seal continuously. Not intermittent spray impact that hits and bounces away. Continuous pressure. The water sits there and pushes. Seals designed to deflect moving water fail under sustained static load from pooled water.

Insurance adjusters know the difference. They deny these claims constantly. "Exposure exceeding rated conditions." The denial letter quotes the IEC standard and shows exactly where IPX5 testing stops. The homeowner thought water resistant meant handles rain. Rain yes. Puddles no. A puddle is not rain falling on the enclosure. A puddle is the enclosure sitting in water. Completely different test. IP65 never took that test.

IP67 adds submersion testing at 1 meter depth for 30 minutes. Costs maybe 10-15% more on comparable products. For any ground-level install, that 10-15% premium is trivial compared to replacing a flooded battery.

IP67 adds submersion testing at 1 meter depth for 30 minutes. Costs maybe 10-15% more on comparable products. For any ground-level install, any low wall mount, anywhere water might pool during a bad storm, anywhere drainage might fail during a twenty-year weather extreme, that 10-15% premium is trivial. Trivial compared to replacing a flooded battery. Trivial compared to fighting a denied insurance claim. Trivial compared to the argument with the warranty department about whether standing water counts as misuse.

Gaskets Are The Whole Story

Everything about long-term IP65 reliability comes down to gasket material and gasket design. Everything.

Two batteries sit on a distributor shelf. Both say IP65. One uses silicone gaskets from Dow or Momentive or Shin-Etsu, established chemical companies with decades of elastomer formulation experience. The other uses whatever EPDM the procurement department found cheapest that quarter from whoever won the bid.

The IP65 rating printed on both boxes is identical. The field performance over ten years is not.

Silicone rubber costs three or four times more than EPDM. Raw material pricing, not retail markup. It works from -55°C to 200°C without losing elasticity. Below that range it stiffens but does not crack. Above that range it softens but does not melt. It resists UV degradation that destroys other elastomers. It resists ozone attack that cracks ordinary rubber. It holds sealing pressure for a decade at normal operating temperatures without much creep.

Premium silicone formulations from established chemical suppliers perform consistently batch to batch, year to year. The additive packages are dialed in. The quality control catches variation. Generic silicone sourced from whoever offered the lowest price that quarter performs less consistently. The base chemistry looks similar on paper. The stabilizers, the plasticizers, the cure systems differ. Long-term aging behavior diverges. Some batches hold up. Some do not.

EPDM costs less. It also loses 30-40% of its sealing force over ten years under sustained compression. The relationship between temperature and degradation rate is roughly exponential. Degradation doubles for each 10°C increase in sustained temperature. A battery mounted on a sun-baked west-facing wall in Phoenix, where enclosure surface temperatures hit 60°C on summer afternoons, ages its gaskets far faster than a battery in a temperature-controlled Seattle garage that never sees 30°C.

The Certification Gap

Both batteries carry IP65 ratings. Both passed the same certification test on the assembly line. Both were tested at room temperature on brand-new units. The Phoenix battery started seeping moisture at year six when the EPDM had crept enough to drop below sealing threshold. The Seattle battery will probably still pass IP65 testing at year fifteen. Same product. Same rating. Different outcomes. The rating told you nothing useful about the difference.

The IEC 60529 standard includes no requirement for accelerated aging tests before certification. Zero. A manufacturer can design a product that passes IP65 handsomely when new and predictably fails at year five, and the certification remains technically valid. The rating describes a snapshot of performance at one moment in time under one set of conditions. Not a trajectory. Not a prediction. Not a guarantee. A snapshot.

Some manufacturers run internal aging protocols before releasing products. They bake sample enclosures at elevated temperature for weeks, simulating years of thermal stress in compressed time. They cycle humidity chambers to stress seals with repeated moisture exposure. They blast samples with UV equivalent to years of sun. Then they retest to IP65. Products that still pass after artificial aging have better field survival rates than products certified fresh off the line and never retested.

But nothing requires this extra validation. Nothing even encourages it. The testing costs money and takes time. The manufacturer who skips aging validation ships product faster with the same IP65 stamp on the box as the manufacturer who spent six extra months proving durability. The customer cannot tell the difference at purchase. The difference shows up at year six when one product is still sealed and the other is full of moisture.

Asking manufacturers about gasket materials produces nothing useful. The product manager usually does not know the specific compound. The sales rep definitely does not know. The engineer who specified it left the company two years ago and the replacement inherited the BOM without questioning it. Asking about warranty claim rates for moisture-related failures produces even less. That data exists somewhere in a service department spreadsheet that nobody in sales has ever seen and nobody in marketing wants to share because the numbers might look bad.

The information that actually predicts field reliability lives in installer forums, in the accumulated experience of people who have installed hundreds of units across multiple brands and watched what fails, in warranty claim patterns that never get published, in hard experience from customers who got burned and posted about it. Brand reputation built over years of field installations carries more signal than any datasheet comparison. Which disadvantages newer market entrants regardless of whether their engineering is actually good. A new brand with excellent gasket engineering cannot prove it except by accumulating years of field history. The incumbents with mediocre gaskets but long track records keep winning bids on reputation alone.

Environmental Factors The Test Ignores

Standard IP testing uses deionized fresh water at room temperature on new equipment. Real installations face conditions the test does not simulate.

Coastal installations face salt fog exposure that standard IP testing never simulates

Coastal installations deal with salt fog. Sodium chloride deposits pull moisture from humid air and form thin electrolyte films on surfaces. These films accelerate corrosion by an order of magnitude compared to fresh water. Salt also crystallizes and dissolves repeatedly as temperature and humidity cycle. Crystals growing against gasket surfaces abrade the sealing faces microscopically. Invisible damage per cycle. Accumulated over years, that grinding opens leakage paths where none existed at installation.

Some installers near the Gulf Coast and Tampa Bay learned this early in the residential storage market. Same products that performed fine sixty miles inland in Orlando started generating service calls within three years near the coast. Corroded terminals, degraded seals, moisture inside enclosures. The only variable was proximity to saltwater. Now some of those installers refuse anything below IP67 within five kilometers of the coast, and they spec stainless steel fasteners and supplementary marine coatings regardless of what the manufacturer says is adequate.

Desert installations experience extreme thermal cycling that accelerates gasket degradation exponentially

Nobody tests IP65 at 55°C enclosure surface temperature, which happens routinely on sun-exposed walls in hot climates. Dark enclosures on west-facing walls in desert regions hit 65°C on summer afternoons. The gaskets that sealed fine at 25°C during factory testing behave differently at 65°C. Silicone handles it. EPDM softens and creeps faster under compression, accelerating permanent deformation.

Tests after 3000 thermal cycles. A decade of service means roughly 3650 day-night temperature swings. Each swing flexes every gasket interface as aluminum housings and rubber seals expand and contract at different rates. The movement per cycle is tiny. Accumulated across thousands of cycles, that micro-movement fatigues adhesive bonds and work-hardens elastomer surfaces.

West-facing walls see the worst thermal stress. The enclosure heats all afternoon as sun tracks across the sky. Then the sun drops and temperature falls fast. Rapid cooling creates stronger negative pressure pulses inside the enclosure than gradual cooling. That negative pressure sucks against every seal, trying to draw outside air through any pathway. Repeated stress in the same direction accumulates damage in ways that random stress does not.

Tests after five years of UV exposure. Polycarbonate windows yellow and crack. ABS housings chalk and become brittle. Rubber compounds harden and develop surface cracks that propagate inward. The certification catches the product at its best moment. Everything after shipment is degradation, managed only by design margin and material quality that the IP rating does not describe.

IP65 vs IP67

IPX5 tests dynamic impact. Water hits the surface, flows off, splashes away. Labyrinth structures and drainage channels work well. Moderate gasket compression suffices because the water is not trying to push through. It is trying to find an open path, and the design blocks open paths.

IPX7 tests static pressure. Water surrounds the enclosure and presses inward continuously for thirty minutes at one meter depth. About 100 millibar of pressure, not much in absolute terms, but constant and omnidirectional. Labyrinths that drained spray beautifully now trap water against secondary seals. The water is not looking for an open path. The water is pushing on everything, probing every weakness, exploiting any gap where seal pressure falls below threshold.

Same gasket material, same compression ratio, different seal geometry, completely different outcome. Products engineered to deflect jets may flood during immersion. Products engineered for immersion may be overbuilt for spray deflection. The IP rating does not distinguish between "barely passes IPX5" and "would easily survive IPX7 if anyone bothered to test it."

Tesla Powerwall

That choice eliminates installer judgment calls about site conditions. No evaluation needed for pooling risk. Everything goes wherever the customer wants without shelter requirements or mounting height restrictions. Simplifies sales. Absorbs cost premium into overall pricing.

GivEnergy

Offers IP65 with shelter recommendations in the installation manual. Buyers with suitable protected mounting locations save money. Buyers who ignore the shelter guidance and encounter pooling water during a storm discover why the guidance exists.

BYD

Produces IP55 units targeting indoor installation. Lower rating, lower material cost, lower price. Works perfectly for the intended application. Fails when installers treat IP55 as interchangeable with IP65 and mount units in semi-outdoor locations.

For a wall position under a solid roof overhang, IP65 provides adequate protection. For ground level mounting, low wall positions, areas with drainage uncertainty, flood zones, or locations where a twenty-year weather extreme might create temporary pooling, IP67. The price difference runs 10-15%. The protection difference is not proportional. It is categorical. Binary. Handles submersion or does not.

Maintenance

Gaskets should be inspected annually for cracking, hardening, or compression set. Enclosure fasteners should get torque verification because thermal cycling loosens threaded connections gradually over years. A bolt that lost 25% of clamping force still looks tight to visual inspection, but the gasket underneath may have dropped below sealing threshold. Vent membranes need debris clearance. Cable gland seals need integrity checks.

Almost no residential installation receives this maintenance. The installer mentions it during commissioning. The homeowner nods. The manual includes a maintenance schedule in small print somewhere around page forty. Actual execution rate approaches zero. The battery sits for years. Gaskets age. Fasteners back out. Vents clog with debris and spider webs. Then water gets in and the warranty claim triggers an argument about whether maintenance requirements were followed.

The IP65 rating assumes seals remain in their certified condition indefinitely. The real world assumes the owner handles upkeep. The gap between these assumptions widens every year until something fails.

Building margin for the maintenance that will not happen means choosing higher IP ratings than minimum site conditions require. It means selecting mounting locations that minimize environmental stress. It means accepting that real systems eventually leak and planning accordingly. The alternative is actually performing the maintenance, which requires someone to remember, someone to schedule, and someone to show up with a torque wrench and a flashlight. Honest assessment of whether that will actually happen should inform equipment selection.

What The Rating Means

IP65 certifies that a new unit blocked dust under negative pressure for eight hours and blocked water jets from all angles for three minutes, at room temperature, using fresh water.

The rating says nothing about submersion. Nothing about salt or UV aging or thermal cycling. Nothing about gasket material or manufacturing consistency or supplier quality. Nothing about how long the protection persists. Nothing about what happens when maintenance gets skipped.

For sheltered mounting locations in mild climates with owners who actually perform maintenance, IP65 provides adequate margin. For exposed installations, harsh environments, coastal proximity, or realistic expectations about maintenance neglect, spend the extra 10-15% on IP67 and choose a mounting position with good drainage. The two digits describe a controlled lab result on new equipment. Field performance over fifteen years depends on factors the certification protocol never measures.