How to Extract Lithium from Battery?

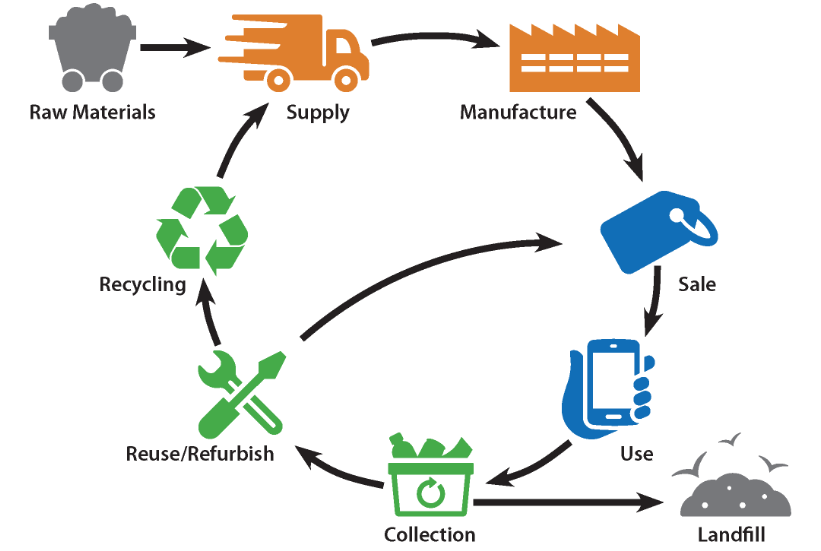

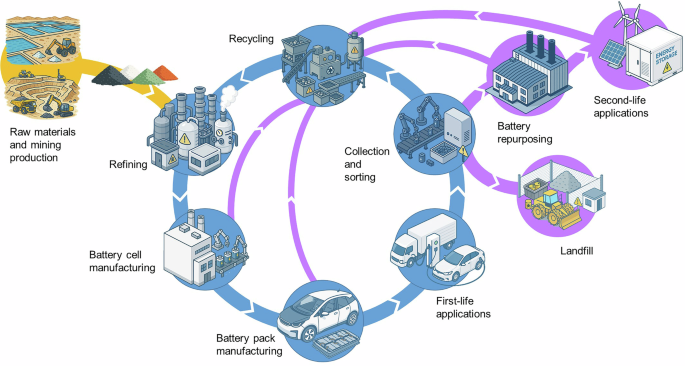

The global battery recycling industry: most facilities that claim to recycle lithium batteries do not actually extract lithium. They recover cobalt and nickel because these metals command higher prices and the extraction chemistry is well established, then sell the lithium-bearing slag to cement plants as sintering additive. Lithium, the element that defines these batteries, gets treated as waste. This absurdity exposes a fundamental technical bottleneck that industry marketing prefers to obscure: lithium extraction is far more difficult than commonly understood, and existing industrial methods face thermodynamic constraints that no amount of engineering optimization can overcome.

Modern lithium-ion battery cells — the foundation of electric mobility and energy storage systems

What Is Lithium Extraction from Batteries

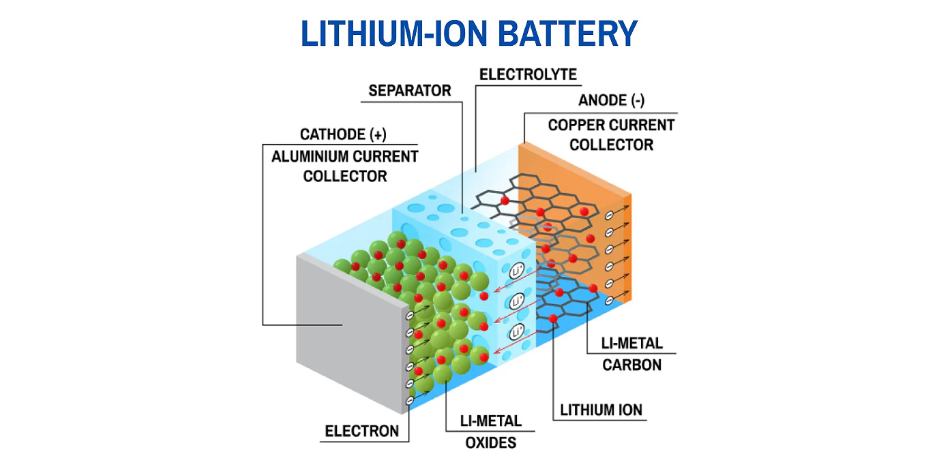

Lithium battery recycling extraction refers to the systematic industrial recovery of lithium compounds from end-of-life batteries or manufacturing scrap through chemical, thermal, or mechanical means. The standard definition glosses over something crucial: the form in which lithium exists within batteries determines extraction difficulty, and this form creates more complications than any other recoverable metal.

Cobalt and nickel exist as oxides within the cathode material's crystal lattice. When acid attacks these materials, dissolution proceeds spontaneously according to thermodynamic favorability. Protons attack metal-oxygen bonds, metal ions enter solution, reaction complete. Lithium behaves differently. Lithium ions occupy intercalation sites between the layered oxide sheets, with weaker coordination to oxygen atoms compared to transition metals. Lithium dissolves more readily from the solid phase, but it also occupies the most disadvantageous position throughout every subsequent separation step. Its coordination ability is weakest, its precipitation solubility product is largest, its extraction distribution coefficient is lowest.

Cross-section view revealing the layered structure of lithium battery electrodes

The easiest element to dissolve from the solid turns out to be the hardest to separate from solution. The entire design logic of lithium recovery processes reflects this awkward reality.

Pyrometallurgy breaks down battery materials through high-temperature smelting above 1400°C. The method exploits differences in oxygen affinity among metals: cobalt, nickel, and copper have lower oxygen affinity and reduce to metallic alloy that sinks to the furnace bottom; lithium, manganese, and aluminum have higher oxygen affinity and oxidize into slag. Lithium exhibits significant vapor pressure at these temperatures. Industrial data consistently show pyrometallurgical lithium recovery rates below 50%, with substantial quantities volatilizing into flue gas or dispersing into amorphous slag phases where further extraction becomes impractical. Engineering cannot fix this. The thermodynamics impose a hard ceiling.

Hydrometallurgy dissolves electrode materials in acid, then separates metals through pH manipulation, solvent extraction, and selective precipitation. This route achieves 90-95% lithium recovery, but at the cost of extraordinary process complexity. The leach solution simultaneously contains Li⁺, Co²⁺, Ni²⁺, Mn²⁺, Fe³⁺, Al³⁺, and Cu²⁺, while lithium's chemical properties place it at a disadvantage in virtually every separation operation.

pH-controlled precipitation follows solubility product order: Fe(OH)₃ precipitates around pH 2.5-3.5, Al(OH)₃ around pH 4-5, Cu(OH)₂ around pH 5-6, and the hydroxides of manganese, cobalt, and nickel between pH 7-9. LiOH has an extremely large solubility product (roughly 5×10⁻¹), meaning it refuses to precipitate at any reasonable pH. Lithium can only remain in the final mother liquor.

Solvent extraction presents similar challenges. Organophosphorus extractants like D2EHPA and PC88A form coordination complexes with metal ions. Complex stability depends on ionic charge density and coordination characteristics. Li⁺ has a large ionic radius (76 pm) with only +1 charge, giving it extremely low charge density and poor complexation ability compared to divalent ions like Co²⁺ and Ni²⁺. Industrial practice extracts cobalt and nickel into the organic phase while lithium remains in the aqueous phase. Reversing this selectivity to extract lithium preferentially is essentially impossible at industrial scale.

Carbonate precipitation follows the same pattern. Li₂CO₃ has a solubility product around 8×10⁻⁴, vastly larger than CoCO₃ (roughly 1×10⁻¹⁰) or NiCO₃ (roughly 1×10⁻⁷). Adding sodium carbonate to a solution containing cobalt and nickel precipitates those metals first. Lithium precipitation must wait until all other metals have been removed.

Lithium is always the last element recovered in industrial processes. Process designers do not neglect lithium; thermodynamics simply forbids its early removal.

Laboratory analysis of battery materials

Industrial chemical processing equipment

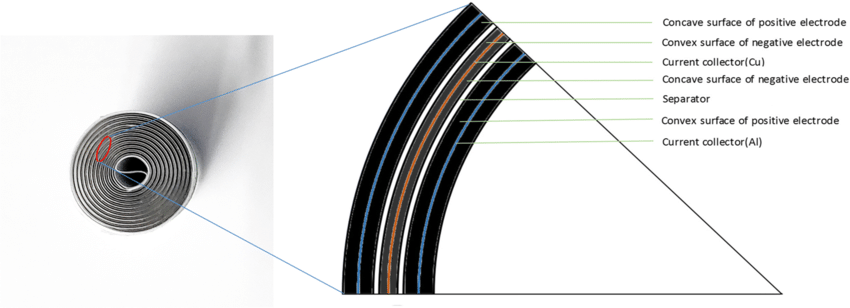

Cathode material crystal structures further complicate extraction chemistry. In layered oxides like LiCoO₂, NCM, and NCA, transition metal oxide layers alternate with lithium layers. During acid leaching, protons first attack the lattice surface. Lithium ions, being weakly coordinated, dissolve preferentially, but this creates a transition-metal-rich passivation layer on particle surfaces that impedes further dissolution. Operations must add reducing agents (H₂O₂ or Na₂SO₃) to disrupt this passivation layer, otherwise leaching efficiency collapses.

Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄) presents entirely different challenges. The olivine structure contains strong Fe-O-P covalent bond networks, giving it far greater lattice stability than layered oxides. Standard sulfuric acid leaching is essentially ineffective against LFP because iron does not dissolve in dilute sulfuric acid. More aggressive conditions become necessary: acid concentrations above 4M, temperatures exceeding 90°C, or switching to hydrochloric or nitric acid systems. Hydrochloric acid brings chlorine gas evolution and severe equipment corrosion, while nitric acid costs more and generates NOx emissions. LFP recycling has long occupied an economically marginal position, and many recyclers simply refuse to accept this material.

When people discuss "battery recycling," they actually mean ternary material (NCM/NCA) recycling. Lithium cobalt oxide remains worth processing because of cobalt's value. LFP, the dominant chemistry in energy storage systems and lower-cost electric vehicles, is forming a massive recycling blind spot.

Why Extract Lithium from Spent Batteries

The case for lithium recovery typically rests on three narratives: environmental benefits, resource security, and economic viability. Each argument has been stretched well beyond what evidence supports.

Environmental claims deserve skepticism

The widely cited claim that recycled lithium reduces carbon emissions by 75% compared to mined lithium originates from Oak Ridge National Laboratory, but it rests on idealized assumptions: 100% lithium recovery rates, clean electricity powering recycling facilities, and comprehensive battery collection systems. Reality involves pyrometallurgical processes consuming 8-12 GJ per ton (mostly from fossil fuels) and hydrometallurgical processes generating substantial acidic wastewater and heavy metal sludge. When these actual burdens enter the calculation, recycling's carbon advantage shrinks considerably.

Primary lithium extraction from natural deposits remains essential to meet global demand

Recycling only processes batteries that already exist, while lithium demand growth comes primarily from new vehicles and energy storage systems. Even if global battery recycling reached 100% (physically impossible because product lifecycles mean end-of-life battery supply always lags new battery demand by 5-15 years), recycled lithium could satisfy at most 15-20% of demand growth by 2030. Primary mining must supply the rest. Environmental narratives position recycling as an "alternative" to mining, but it functions only as a supplement.

Resource security arguments collapse under scrutiny

The United States imports over 95% of its lithium requirements, a figure frequently invoked to justify domestic recycling's strategic value. Where does U.S. lithium "demand" come from? Primarily battery manufacturing. The United States has virtually no domestic battery cell manufacturing capacity. Cells arrive mainly from China, Korea, and Japan. Within this supply chain structure, domestically recycled lithium has no domestic factories to consume it. Unless battery manufacturing also returns, recycled lithium either gets exported or accumulates in warehouses.

The genuine resource security logic is not "recycle lithium to reduce import dependence" but "build complete domestic battery supply chains, with recycling as one component." Treating recycling as a standalone strategic initiative confuses cause and effect.

Economic Reality Check

Lithium recycling economics reduce to simple arithmetic: does recovery cost less than the market price of equivalent-purity lithium compounds? The answer fluctuates violently with lithium prices. At the 2022 price peak (lithium carbonate around $80,000/ton), almost any recycling operation generated profit. By 2024, with prices retreating to $10,000-15,000/ton, substantial recycling capacity fell into losses or shutdown.

Economics swing violently with commodity prices

Lithium recycling economics reduce to simple arithmetic: does recovery cost less than the market price of equivalent-purity lithium compounds? The answer fluctuates violently with lithium prices. At the 2022 price peak (lithium carbonate around $80,000/ton), almost any recycling operation generated profit. By 2024, with prices retreating to $10,000-15,000/ton, substantial recycling capacity fell into losses or shutdown.

Hydrometallurgical cost structures are dominated by reagent consumption (sulfuric acid, hydrogen peroxide, sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate) and energy consumption, all relatively inflexible. When lithium prices fall, recyclers cannot cut costs to maintain margins. They can only wait for prices to recover. Investment decisions across the industry have taken on speculative characteristics.

One structural factor receives less attention than it deserves: cobalt. In ternary batteries, cobalt constitutes roughly 10-20% by mass, with prices typically $30,000-50,000/ton. For high-cobalt materials (LiCoO₂, NCM111), cobalt recovery value may exceed lithium recovery value. Lithium recycling economics are substantially subsidized by cobalt. As battery materials evolve toward high-nickel low-cobalt formulations (NCM811, NCA) or cobalt-free chemistries (LFP, manganese-based materials), this subsidy disappears. Future lithium-only recycling, without cobalt value support, faces more severe economic challenges.

The actual industry driver may be none of the above, but regulation. EU Battery Regulation mandates 70% recycling efficiency by 2030 with specific lithium recovery rate targets. California and China are following. These mandatory requirements transform recycling from economic decision to compliance cost, providing recyclers with institutional protection regardless of market prices. Producers must pay for recycling whether it makes economic sense or not.

When Should Batteries Be Processed for Lithium Recovery

State of charge determines explosion risk

This is the most important safety variable in recycling, yet also the most commonly misunderstood by the public and non-specialist practitioners.

Intuition suggests "lower charge equals safer." This holds true in most cases, but one lethal exception exists: over-discharge. When lithium-ion battery voltage drops below normal cutoff voltage (typically 2.5-3.0V), complex side reactions occur at the negative electrode. Copper current collectors begin dissolving (Cu → Cu²⁺ + 2e⁻). Lithium ions can no longer intercalate normally into graphite layers and instead deposit on the negative electrode surface as metallic lithium.

Battery safety protocols are critical throughout the recycling process

Metallic lithium is hazardous. It reacts violently with water (2Li + 2H₂O → 2LiOH + H₂↑), reacts with atmospheric moisture, and reacts with nitrogen to form lithium nitride. Batteries containing metallic lithium deposits may spontaneously ignite during disassembly. Post-incident analyses of multiple recycling facility fires have traced back to improper handling of over-discharged batteries.

The ideal processing state is 30-50% state of charge. Stored electrochemical energy remains low enough that even internal short circuits release insufficient heat to trigger thermal runaway. Lithium exists in Li⁺ ionic form within cathode materials, chemically stable. No metallic lithium deposition risk exists at the negative electrode. Electrolyte components have not yet undergone accelerated decomposition from prolonged full-charge storage.

Achieving this ideal state proves difficult. Consumer electronics batteries typically reach recycling completely depleted (otherwise users would continue using them). Electric vehicle batteries retire in a degraded state where actual state of charge may be high or low. Recycling facilities must handle incoming materials across the entire state-of-charge spectrum, making standardized discharge pretreatment essential.

Salt water immersion remains most common for industrial discharge: batteries soak in 5-10% sodium chloride solution for 24-72 hours. The ionic conductivity enables self-discharge while water presence suppresses potential combustion. This method has flaws. Large battery packs discharge unevenly, with outer cells depleting while inner cells may retain substantial charge. Opening packages to verify inner cell status exposes potentially undischarged cells. Salt water corrodes casings and terminals. Concentrated discharge heat may trigger localized thermal runaway. A 2021 incident at a Korean recycling facility (not named in public reports, though industry publications covered the event) was attributed to exactly this uneven internal/external discharge phenomenon causing inner cell thermal runaway.

Resistive discharge with controlled loads offers more precision but requires interface matching for each battery type, processes slowly, and demands significant equipment investment. Currently this approach sees use mainly for large electric vehicle battery packs.

Battery degradation affects extraction chemistry

Retired batteries differ from fresh batteries in extraction chemistry. Cycling-induced aging causes cathode material lattice defects to accumulate, with transition metals converting from layered structures toward rock-salt phases and dissolution behavior changing accordingly. SEI film (solid electrolyte interphase) continues growing, consuming lithium salts from electrolyte and reducing lithium content at the negative electrode. Electrolyte decomposition generates various organic byproducts that complicate downstream processing.

Moderately aged batteries (60-80% remaining capacity) often represent ideal recycling feedstock. Deeply aged batteries (below 50% remaining capacity) present more problems, with some lithium permanently locked in structural defects beyond recovery.

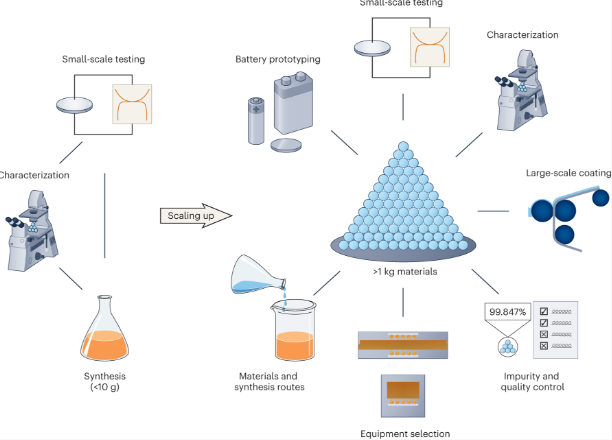

Manufacturing scrap represents the highest-quality feedstock. These materials never experienced cycling, exist in chemical states nearly identical to fresh synthesis, and offer uniform composition with traceable origins. Recyclers willingly pay premiums for manufacturing scrap. Some large battery factories have established direct scrap supply agreements with recyclers, representing the most stable business model in the recycling industry.

The Five Competing Extraction Technologies

Five primary technical routes compete in industry. Their maturity levels and actual deployment scales differ enormously, and market communications tend to blur these distinctions.

Advanced industrial processing facilities for battery material recovery

Pyrometallurgy

Pyrometallurgical processing is the oldest technical route, essentially treating battery materials as ore for smelting. The Umicore facility in Belgium typifies this approach: mixed batteries enter electric arc furnaces or rotary kilns, organic components combust to provide heat, metal oxides undergo reduction reactions at high temperature, ultimately yielding cobalt-nickel-copper alloy and lithium-manganese-aluminum slag.

This method survives today because it accepts mixed feedstock without pretreatment. Batteries can enter directly without sorting by type, without discharge, without disassembly. For markets with underdeveloped collection systems and heterogeneous feedstock sources, this capability has value.

Energy consumption of 8-12 GJ per ton of battery runs three to four times higher than hydrometallurgy. Lithium recovery rates below 50% mean the remainder volatilizes into flue gas or disperses in slag. Fluorine-containing flue gases require expensive treatment systems. The cobalt-nickel alloy still requires further hydrometallurgical processing to yield usable salt products. The entire process's carbon footprint and environmental burden show no clear advantage over primary mining.

As cathode materials shift from high-cobalt (LiCoO₂) toward high-nickel low-cobalt (NCM811) and eventually cobalt-free (LFP), pyrometallurgical economics deteriorate rapidly. Cobalt is the only high-value metal in the alloy. Without cobalt's subsidy, nickel-only recovery generates thin margins. Current investment in pyrometallurgical capacity carries substantial risk.

Hydrometallurgy

Over 90% of actual global lithium recovery capacity uses hydrometallurgical routes. Redwood Materials, Li-Cycle, GEM, Brunp, and other leading companies all employ hydrometallurgical processes. This dominance reflects not excellence but the fact that alternatives have worse problems.

Reagent consumption creates a troubling material flow. For NCM cathode materials, leaching one ton of black mass requires roughly 1.5-2 tons of sulfuric acid, 0.3-0.5 tons of hydrogen peroxide, substantial sodium hydroxide for pH adjustment, and sodium carbonate for lithium precipitation. These reagents are consumed once and cannot be recycled. Recycling lithium batteries requires consuming large quantities of chemical products, and those chemical products themselves carry significant environmental footprints in production. Where system boundaries are drawn determines whether recycling's environmental accounting works out favorably.

Hydrometallurgical processing tanks

Modern recycling facility infrastructure

Wastewater treatment imposes hidden costs. Hydrometallurgical processes generate large volumes of high-salt, high-acid wastewater containing heavy metals. Compliant treatment (neutralization, heavy metal precipitation, evaporative concentration) costs in many regions exceed the value increment from battery material recovery itself. Some non-compliant operations evade costs through dilution discharge or off-site dumping, forming a dark irony against recycling's environmental rationale.

Solvent extraction poses technical barriers that newcomers frequently underestimate. Cobalt-nickel separation requires multi-stage countercurrent extraction, demanding precise organic/aqueous phase ratio control, stable interface behavior, and efficient phase separation. Organic extractants like D2EHPA are expensive, and losses must be controlled to very low levels. Many new entrants encounter problems in actual operation: incomplete cobalt-nickel separation, extractant emulsification, product purity failing specifications. The engineering difficulty of this step has sunk more than a few ambitious startups.

LFP creates economic difficulties. Hydrometallurgical processing of LFP is technically feasible but economically problematic. LFP contains no cobalt or nickel, leaving only lithium and iron for recovery. Iron has near-zero value. LFP dissolution is more difficult than NCM, requiring harsher conditions and thus higher costs. Current market quotes for LFP recycling often require the battery holder to pay, sometimes not even covering transport costs.

Mechanochemistry

Mechanochemical methods use ball milling to generate localized high temperature and pressure that drive solid-state reactions. Aluminum powder serves as reducing agent, capturing oxygen from cathode materials during milling to form aluminum oxide while releasing lithium. Theoretically this route offers extremely high energy efficiency (below 1 GJ/ton), uses no acid or alkali reagents, and yields simple products.

Nobody has made it work beyond pilot scale. Ball mills have low throughput, suffer severe equipment wear from hard ceramic particles in battery materials, and achieve reaction conversion rates limited by milling time. Reaching 90%+ lithium recovery may require several hours of milling, which at industrial scale means extremely low capacity and high equipment investment. Cost structures and reliability remain unknown quantities. Distributed small-scale recycling or remote locations without acid-alkali supply might eventually find mechanochemical methods useful.

Direct recycling

Direct recycling does not decompose cathode materials but rather restores electrochemical performance through relithiation and re-sintering. This preserves original cathode particle morphology and crystal structure while avoiding the enormous energy consumption of elemental resynthesis.

Research at Worcester Polytechnic Institute showed regenerated cathode materials achieving 98% of original material performance. Theoretical energy savings exceed 80%. Recycling researchers have chased this approach for over a decade.

The obstacle is feedstock purity. Different cathode materials (NCM111, NCM523, NCM622, NCM811, LCO, LFP...) must be strictly separated. Even mixing different batches of the same type may cause regeneration failure because lithium stoichiometry, elemental ratios, and crystal parameters all differ, making relithiation quantities and sintering conditions incompatible. Consumer electronics batteries come from mixed sources with numerous models and unclear labeling. Electric vehicle battery models are more concentrated, but materials from different years and different suppliers still vary. The only feedstock capable of meeting direct recycling requirements is single-source manufacturing scrap from battery factories, which limits the approach to closed-loop industrial applications rather than broad end-of-life battery processing.

Deep eutectic solvents

Deep eutectic solvent (DES) extraction methods use mixed solvents composed of choline-class compounds and ethylene glycol, selectively dissolving lithium through coordination chemistry. Combined with microwave heating, 87% lithium recovery is achievable in 15 minutes.

Industrialization faces hard constraints. Choline chloride prices run 10-20 times higher than sulfuric acid. Multiple solvent recycling cycles cause metal impurity accumulation and coordination capacity decline. DES viscosity far exceeds aqueous solutions, limiting mass transfer and making large reactor implementation difficult. Academic interest remains high, but commercial prospects are distant.

How Hydrometallurgy Actually Works

Since hydrometallurgy dominates the industry, the details of this process deserve close examination. The textbook version omits most of what makes or breaks actual operations.

Discharge and disassembly

When batteries arrive at recycling facilities, the first safety checkpoint is discharge. Industry consensus places the safety threshold at residual charge below 5%, but achieving this state reliably remains methodologically contested.

More reliable approaches than salt water immersion combine forced discharge with real-time monitoring: conducting resistive discharge on each module or cell individually, monitoring voltage curves until confirmed below safety thresholds. This requires numerous discharge stations and manual or automated wiring operations, significantly increasing costs. Compromise approaches begin with salt water immersion for preliminary discharge, then disassemble under inert atmosphere, then perform voltage testing and supplementary discharge on exposed cells as needed.

Careful disassembly procedures are essential for safe battery processing

Disassembly itself presents difficulties. Battery pack designs optimize for safety and energy density but give almost no consideration to recycling convenience. Laser-welded bus bars, potting compound-filled gaps, precision-fit structural components make automated disassembly extremely challenging. The vast majority of battery disassembly currently remains manual, with high labor intensity, low efficiency, and significant safety risks.

Electrolyte handling is another underestimated step. Residual electrolyte in end-of-life batteries (carbonate solvents plus lithium hexafluorophosphate) may seem small in volume but carries high toxicity and reactivity. Lithium hexafluorophosphate hydrolyzes in the presence of moisture to form hydrogen fluoride (HF), a substance capable of penetrating skin and causing potentially fatal fluoride poisoning. Electrolyte must be extracted in dedicated ventilated areas, with workers wearing full-face supplied-air respirators and chemical protective suits.

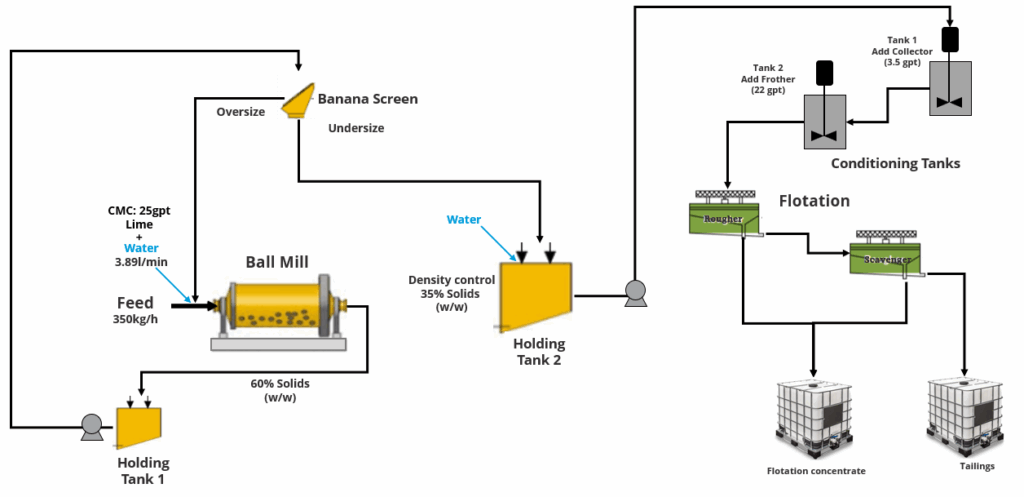

Mechanical processing and black mass preparation

Disassembled electrode materials require size reduction to particle sizes suitable for chemical processing. This constitutes the highest fire-risk step in the process chain.

Aluminum foil, copper foil, active materials, and carbon black mix together. Crushing generates large quantities of conductive dust. Metal dust is inherently flammable, and fine aluminum powder in air may explode. Proper facilities must conduct crushing under inert atmosphere (N₂ or CO₂) or underwater. Inert atmosphere operation costs are high, and underwater crushing introduces subsequent drying steps and wastewater issues. Many small and medium recycling facilities cut corners at this step, with resulting fire incidents occurring regularly.

Crushed material requires classification. Vibrating screens separate large metal pieces (current collector fragments) from fine powder. Air classification exploits density differences for further separation: carbon black and PVDF binder have low density and are carried away by airflow; cathode oxides have high density and settle for collection. Magnetic separation removes ferromagnetic contaminants.

These steps yield "black mass," the feedstock for subsequent chemical processing. Typical composition: cathode active material (60-70%), graphite (20-30%), residual metals (5-10%), binder and other (around 5%). Black mass quality, particularly metal content, particle size distribution, and impurity levels, directly affects leaching efficiency and final product purity.

Acid leaching

Acid leaching converts solid-state metal oxides into separable solution-phase ions. The reaction chemistry appears simple on the surface. For NCM:

This equation conceals complex kinetic realities. Acid leaching is a solid-liquid heterogeneous reaction controlled by surface reaction kinetics, product diffusion, and solid-state diffusion. Under industrial conditions (80-90°C, 2-4M H₂SO₄), the first two hours proceed rapidly (surface reaction controlled), then slow significantly (diffusion controlled). Achieving 95%+ leaching rates typically requires 3-4 hours.

Hydrogen peroxide plays a vital but costly role. Without oxidizing agent, Mn remains as +4 oxide (MnO₂ does not dissolve in dilute sulfuric acid), and Ni and Co leaching remains incomplete. H₂O₂ self-decomposes under hot acidic conditions (2H₂O₂ → 2H₂O + O₂), with effective utilization typically only 30-50%, the remainder lost entirely.

Temperature control involves delicate balancing. Higher temperatures accelerate reactions but also accelerate H₂O₂ decomposition and acid evaporation losses. Industrial facilities typically employ gradient heating: initial stages at 60-70°C allow orderly reaction initiation, mid-stages rise to 80-90°C to accelerate leaching, final stages may return to 70°C to reduce reagent losses.

Solid-liquid separation after leaching appears straightforward but presents difficulties. Graphite and undissolved fine particles in black mass form mud-like slurries that resist filtration. Filter press cloth selection, feed methods, and washing procedures all matter.

Separation and purification

Pregnant leach solution contains all dissolved metal ions: Li⁺, Ni²⁺, Co²⁺, Mn²⁺, plus impurities Fe³⁺, Al³⁺, Cu²⁺, and others. Separation aims to recover each in high-purity form.

Iron, aluminum, and copper are impurities requiring removal first. Adjusting pH to 3-4 precipitates iron and aluminum as hydroxides; continuing to pH 5-6 precipitates copper. These precipitates have no recovery value after filtration and are treated as hazardous waste.

Two routes exist for manganese. Oxidative precipitation at pH 5-6 with air sparging oxidizes Mn²⁺ to MnOOH precipitate. Alternatively, manganese remains in solution for separation by subsequent solvent extraction. Both routes see industrial use.

Precision separation equipment for metal recovery processes

Cobalt and nickel have extremely similar chemical properties, making pH precipitation essentially incapable of separating them. The only industrially viable method is solvent extraction with D2EHPA or derivatives. The selectivity window is narrow (typically only 0.5-1 pH unit), requiring precise control. Industrial facilities employ multi-stage countercurrent extraction to amplify this small difference: aqueous phase enters from one end, organic phase enters from the other, flowing in opposite directions through multiple mixer-settlers. Each stage achieves partial separation; cumulative effect reaches high purity.

Typical cobalt-nickel separation requires 6-10 extraction stages plus 6-10 washing stages plus 4-6 stripping stages. The entire extraction system occupies the facility's core area and represents major capital investment.

After cobalt enters the organic phase, dilute sulfuric acid stripping returns it to the aqueous phase, yielding high-purity cobalt sulfate solution. Nickel remains in the aqueous raffinate for direct crystallization or further purification.

After all preceding steps, the solution contains primarily lithium (as Li₂SO₄) and sodium (from NaOH used for pH adjustment). Lithium recovery proceeds via carbonate precipitation:

Li₂CO₃ solubility is approximately 13 g/L at 25°C. Solution must be concentrated to 30-50 g/L lithium to achieve high precipitation yields. Concentration occurs through evaporation, with considerable energy consumption. Precipitation proceeds at 85-95°C (Li₂CO₃ solubility anomalously decreases at higher temperatures). Crystals are washed and dried after precipitation.

Product purity is decisive. Battery-grade lithium carbonate requires Li₂CO₃ > 99.5%, Na < 200 ppm, Fe < 10 ppm, with strict limits on other impurities. Lithium carbonate failing battery-grade specifications can only be sold at lower grades to glass, ceramics, and other low-value applications, at prices possibly only 30-50% of battery-grade. This represents the critical profit watershed for recyclers.

Safety Failures and How to Prevent Them

Thermal runaway

Thermal runaway is a disaster mode unique to lithium batteries. Once internal temperature exceeds a critical threshold (typically 150-200°C, depending on chemistry), cathode materials begin decomposing and releasing oxygen. Exothermic reactions with electrolyte occur, temperature rises further, triggering more decomposition. This self-accelerating positive feedback loop causes temperatures to spike to 600-1000°C within seconds to tens of seconds, with violent combustion or explosion.

Advanced safety monitoring systems protect against thermal events

Once thermal runaway occurs, extinguishment is extremely difficult. Combustion does not require external oxygen since cathode decomposition generates oxygen. Water poured on reacts with high-temperature metal to produce hydrogen, potentially causing secondary explosions. Conventional extinguishing agents (foam, CO₂, dry powder) have limited effectiveness.

Prevention requires strict discharge procedures, refusing or isolating damaged batteries, and maintaining inert atmosphere protection throughout mechanical processing. Detection requires temperature sensor networks covering all storage and processing areas, monitoring temperature rate of change in real time. Rates exceeding 5°C per minute should trigger alarms. Infrared thermal imaging can remotely detect localized overheating.

If thermal runaway has occurred and cannot be extinguished, the best strategy may be allowing it to burn out under controlled conditions. Dedicated burn-down pits are isolated areas with sand floors and overhead water mist cooling, allowing batteries to burn while preventing fire spread.

Fluorine toxicity

Lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF₆) in electrolyte hydrolyzes to form hydrogen fluoride (HF):

HF hazards far exceed ordinary acids. After penetrating skin, it binds with calcium and magnesium ions in the body, causing electrolyte imbalance and deep tissue necrosis. Skin contact may not cause immediate pain (HF is a weak acid that does not immediately burn like sulfuric acid); by the time pain appears, damage has already penetrated deeply. HF burns covering more than 2% of body surface area (roughly one palm size) can be fatal.

All operations potentially contacting electrolyte must occur in fume hoods or under local exhaust ventilation. Workers wear full-face supplied-air respirators. Calcium gluconate gel is kept available for emergency HF exposure treatment, with calcium ions binding fluoride to prevent tissue penetration. Any suspected fluorine exposure requires immediate medical attention even without symptoms.

Dust explosions

Dust from battery material crushing (mixtures of graphite, aluminum, cathode oxides) can explode when airborne concentrations reach certain levels. Aluminum powder has an extremely low explosive limit (around 40 g/m³) with high explosive force.

The particular danger of dust explosions lies in secondary explosions: the shock wave from an initial explosion lifts more settled dust, forming a second, larger-scale explosion. Multiple industrial incidents show secondary explosions often causing several times the damage of initial explosions.

Crushing equipment operates under inert atmosphere (N₂ or CO₂) or underwater. Dust collection systems incorporate explosion-proof design (relief vents, isolation valves). Facilities prohibit dust accumulation with regular cleaning. Electrical equipment uses explosion-proof models.

Regulatory framework

U.S. EPA classifies spent lithium-ion batteries as characteristic hazardous waste (D001 ignitability, D003 reactivity), subject to full RCRA requirements: hazardous waste identification, reporting, transportation management, and disposal records. State regulations may be stricter. California's 2022 battery management law requires producers to take responsibility for the entire recycling process.

The EU 2023 Battery Regulation introduced the "battery passport," tracking each battery's full lifecycle data from production to recycling.

Regulatory compliance is only the floor. What actually determines safety performance is corporate safety culture: training investment, equipment maintenance, hazard inspection, and systematic incident review. Leading companies like Redwood Materials provide over 60 hours of annual safety training per employee, far exceeding general manufacturing levels.

Preparing Batteries for Recycling

Sorting

Mixing lithium batteries with alkaline batteries is the most common mistake. Alkaline battery recycling follows entirely different pathways, and contamination of lithium battery batches creates processing difficulties and safety hazards.

Within lithium batteries, different chemistries should be separated where possible. LiCoO₂ (lithium cobalt oxide) appears mostly in older phones and laptops, has high cobalt content, and holds highest value. NCM/NCA dominate modern electric vehicles and electronic devices. LFP appears in energy storage systems and some electric vehicles, contains no cobalt or nickel, and has lowest recycling value.

Identification methods: check battery labels and device documentation, or judge by voltage (LFP nominal 3.2V, cobalt/ternary nominal 3.6-3.7V).

Proper sorting of different battery chemistries is essential for safe and efficient recycling

Terminal protection

Exposed battery terminals may accidentally short-circuit during storage and transport. Metal objects, other battery terminals, and conductive packaging materials can all form conductive paths. Short-circuit current causes intense heating and may ignite fires.

Cover positive and negative terminals with insulating tape (electrical tape, masking tape, painter's tape). Cylindrical batteries have positive and negative terminals at opposite ends; apply tape to each end. Wrap tape around tabs on prismatic and pouch cells. Wrap tape around the entire circumference of button cells.

Damaged batteries

Swollen, deformed, burn-marked, or cracked-casing batteries require isolated handling. Place damaged batteries individually in non-flammable containers (metal cans, thick glass jars). Fill with dry sand, vermiculite, or cat litter. Store away from combustible materials. Contact local hazardous waste handlers rather than ordinary recycling points.

Never place damaged batteries in ordinary recycling bins. Under the pressure, vibration, and temperature changes of transport, damaged batteries may undergo thermal runaway before reaching processing facilities, causing fires in logistics and warehouse environments.

Business bulk disposal

Businesses generating large quantities of spent batteries can contact professional recyclers directly, bypassing retail recycling points. Bulk supply advantages include uniform composition facilitating process optimization, high volumes spreading transport costs, and potential for positive recycling value rather than disposal fees.

Electric vehicle battery pack residual values can reach $500-1500, depending on capacity condition and chemistry type. Even after capacity degrades below vehicle-use thresholds, these batteries may first enter second-life applications (energy storage and other less demanding scenarios), with material recycling occurring only after complete retirement.