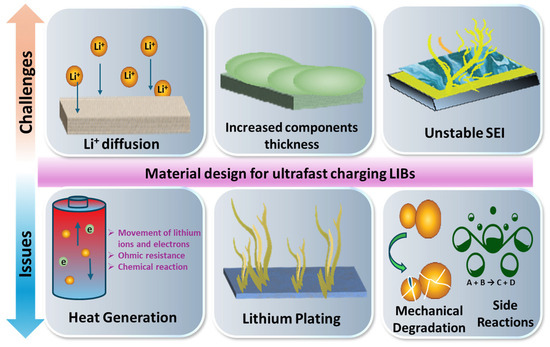

The SEI Problem

The graphite anode in a lithium battery gets coated with a protective layer during the first few charges. This SEI layer (solid electrolyte interphase) forms when electrolyte molecules decompose at the anode surface. Ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate from the electrolyte break down at the low potential of the charged anode, depositing a mix of lithium carbonate, lithium fluoride, and various organic compounds. The layer ends up somewhere between 10 and 50 nanometers thick. It needs to exist because without it, electrolyte decomposition would continue indefinitely and destroy the battery within weeks.

But here's the catch. The SEI layer cracks every time the graphite expands and contracts during charging. Graphite swells about 10% when fully loaded with lithium, then shrinks back. Each cycle opens tiny fractures. Fresh graphite gets exposed. More electrolyte decomposes to patch the cracks. More lithium gets permanently locked into the SEI and exits circulation.

This is where most capacity fade comes from. Not from the electrodes wearing out, but from lithium atoms getting trapped in SEI repair work and never returning to active duty.

The composition of the SEI matters for how fast it grows and how stable it remains. A dense, inorganic-rich SEI resists cracking better than a porous, organic-rich one. Electrolyte additives like vinylene carbonate exist specifically to improve SEI quality during formation. But even the best SEI degrades over time, and there's no way to stop the process entirely.

The SEI also grows during storage, even without cycling. The growth rate follows a square-root-of-time pattern, which means it slows down over months and years but never stops completely. Temperature accelerates everything. The Arrhenius equation governs the relationship, and the practical consequence is that SEI growth roughly doubles for every 10°C increase. A battery stored at 45°C ages about five times faster than one stored at 25°C.

To put numbers on this: activation energy for SEI growth runs around 50-70 kJ/mol in most systems. Plug that into the Arrhenius equation and you get rate multipliers of about 2.2x going from 25°C to 35°C, 4.8x going from 25°C to 45°C, and nearly 10x going from 25°C to 55°C. These aren't approximate. They're predictable from basic thermodynamics, and they show up reliably in accelerated aging tests.

The SOC during storage matters too. Higher voltage means more driving force for parasitic reactions at the anode. At 100% SOC, the graphite sits at around 0.08V versus Li/Li+ reference. At 50% SOC, it sits around 0.12V. That 0.04V difference changes the thermodynamic favorability of the decomposition reactions measurably. A battery sitting at 100% SOC degrades two to three times faster than one sitting at 50% SOC, temperature being equal. Combine high SOC with high temperature and the effect multiplies rather than adds.

This explains why the worst thing to do with a laptop is leave it plugged in at full charge in a warm room for months. The battery barely cycles, but it ages rapidly anyway. Calendar aging doesn't care about cycle count.

Lithium Plating

Plating is the other major degradation mechanism, and it gets far less attention than it deserves in consumer discussions.

When charging happens too fast or too cold, lithium ions arrive at the anode faster than they can squeeze into the graphite structure. Instead of intercalating properly, they pile up on the surface as metallic lithium. This metal is extremely reactive. It immediately starts reacting with electrolyte to form more SEI, consuming active lithium at a rapid rate. Worse, the deposited lithium can grow into needle-like dendrites that eventually puncture the separator and cause internal shorts.

The conditions that trigger plating are specific. Anode potential needs to drop below 0V versus the Li/Li+ reference. Three situations push it there: low temperature (diffusion slows dramatically below 10°C), high charge current (ions arrive faster than diffusion can clear them), and high SOC (fewer vacant sites remain in the graphite, reducing the thermodynamic pull for intercalation).

The combination of all three is devastating. Charging a cold battery that's already at 80% SOC, even at moderate rates, can deposit enough lithium to measurably reduce capacity in a single session. Electric vehicle owners doing winter morning fast charges are playing this game whether they know it or not.

Quantifying the temperature effect: lithium-ion diffusivity in graphite drops by roughly an order of magnitude between 25°C and 0°C. At room temperature, ions landing on the graphite surface diffuse into the particle interior fast enough to avoid pileup at typical charge rates. At freezing, even modest charge rates create surface accumulation.

Once lithium plates, the damage is done. Some of the metal can be recovered during subsequent discharge, but much of it becomes electrically isolated "dead lithium" that permanently exits the usable inventory. Post-mortem analysis of aged cells consistently shows metallic lithium deposits on anode surfaces that experienced cold charging. The correlation between cold-weather fast charging and accelerated degradation shows up in EV fleet data.

Detection is difficult. BMS systems try to infer plating risk from voltage signatures during charging, but the signatures are subtle. The safest approach is prevention through temperature management rather than detection after the fact.

The Cathode Side

Cathode degradation works differently but contributes its own share of capacity loss.

NCM and NCA materials (the nickel-rich layered oxides used in most high-energy cells) undergo structural phase transitions when highly delithiated. At SOC above 80-85%, the crystal lattice contracts along the c-axis by 3-4% during the H2 to H3 transition. Repeated expansion and contraction cracks the cathode particles. Primary particles (around 1 micrometer) and secondary agglomerates (around 10 micrometers) both fracture over time. The cracks increase impedance and expose fresh surface area to unwanted side reactions.

Manganese dissolution is another problem specific to manganese-containing cathodes. Mn ions leach into the electrolyte, drift to the anode, and catalyze additional SEI growth there. This creates a feedback loop between cathode degradation and anode degradation. The dissolved manganese doesn't even need to reach the anode in large quantities. Small amounts catalyze disproportionate SEI growth.

Surface reconstruction happens too. The layered structure at the cathode surface converts to inactive rock-salt or spinel phases over time. These phases don't cycle lithium. Once converted, that capacity is gone permanently.

At extreme delithiation, some oxygen can escape the lattice entirely. This is bad for capacity and bad for safety. Oxygen release feeds into thermal runaway pathways.

The damage from charging between 80% and 100% SOC exceeds the damage from charging between 60% and 80% by a wide margin, even though both represent 20% SOC swings. The voltage curve is steeper near the top, and the structural stress is higher. A cell voltage of 4.0V corresponds roughly to 80% SOC on most NMC cells. Going from 4.0V to 4.2V (full charge) packs the remaining 20% SOC into just 0.2V of voltage rise, and every bit of that voltage increase adds stress.

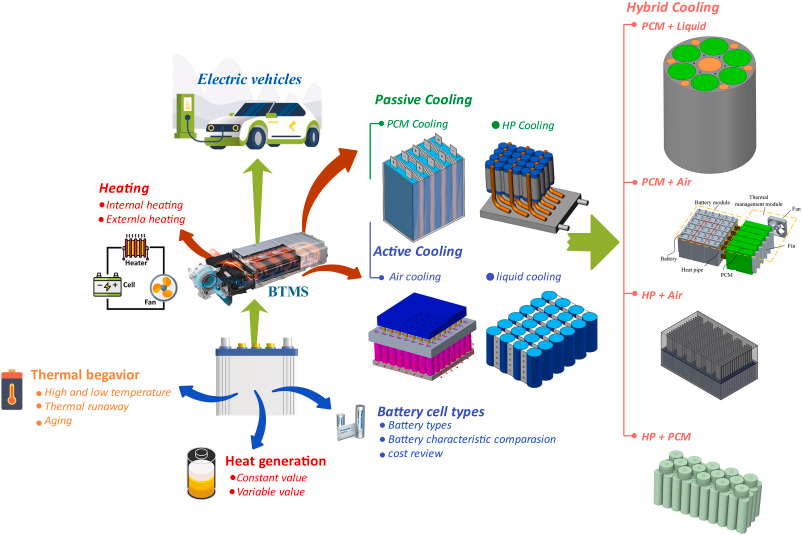

What Temperature Actually Does

Temperature deserves more emphasis than it usually gets. The relationship between temperature and degradation rate is exponential, not linear. Most people underestimate how much this matters.

At 25°C, a well-designed cell might retain 80% capacity after 1000 cycles. At 45°C, the same cell under the same cycling protocol might hit 80% capacity after only 400-500 cycles. At 55°C, maybe 200-300 cycles. These aren't hypothetical numbers. They show up repeatedly in published cycle life data.

Calendar aging shows the same pattern. A year at 100% SOC and 25°C might cost 5-8% capacity. A year at 100% SOC and 45°C might cost 20-25%. The temperature difference alone accounts for a factor of three or four.

Cold temperatures create different problems. Chemical degradation slows down in the cold, which sounds good until you realize that lithium plating risk goes way up. Charging below 0°C is dangerous for battery health even at low rates. The tradeoff between cold storage (which reduces calendar aging) and cold charging (which promotes plating) means the optimal strategy is to store cool but warm up before charging.

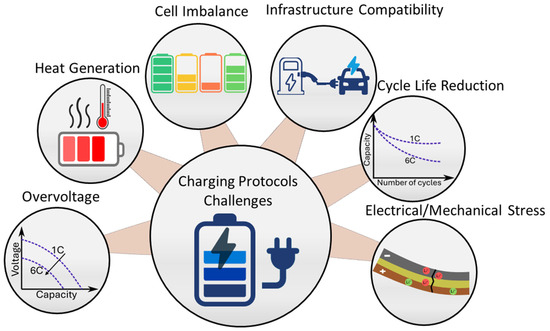

Charge Rate: Overhyped

Fast charging gets blamed for battery degradation more than it deserves.

Yes, high current generates more heat through I²R losses. Yes, high current increases concentration polarization at the electrodes and raises plating risk. But modern cells with good thermal management can handle 1C continuous charging at 25°C without dramatic cycle life penalties. The difference between 0.5C and 1C charging, all else equal, might be 10-20% in total cycle life. Noticeable, but not catastrophic.

Compare this to temperature effects (factor of 2-4x) or SOC management effects (factor of 1.5-2x) and charge rate looks like a secondary concern. Someone who fast charges daily but keeps their phone out of hot cars and avoids overnight 100% charging will probably see better battery life than someone who slow charges but ignores temperature and SOC.

The exception is cold fast charging. Below 10°C, even moderate charge rates can trigger plating. This specific combination deserves its bad reputation. The advice should be "don't fast charge cold batteries" rather than "don't fast charge."

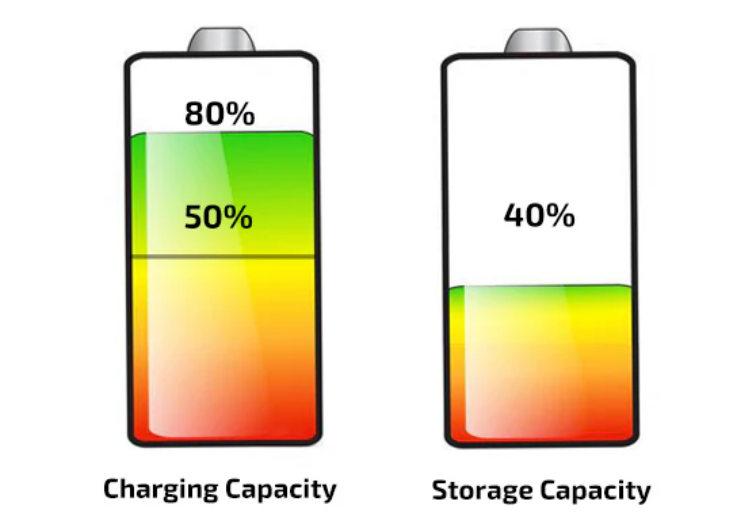

Depth of Discharge

Shallow cycling extends cycle life compared to deep cycling. This is real and well-documented. Halving the depth of discharge roughly doubles the number of cycles to reach a given capacity threshold.

Larger SOC swings mean larger volume changes in the electrodes, more SEI cracking, more particle fracture. A battery cycled between 30% and 70% experiences half the volume swing of one cycled between 0% and 100%, and the stress scales accordingly.

The 20-80% window that gets recommended everywhere makes sense from this perspective. It avoids the high-voltage stress region above 80%, avoids the potential copper dissolution issues below 10-20%, and keeps the volume swings moderate.

Practical Application

For phones, temperature management matters most. Don't charge while gaming. Don't leave the phone on a car dashboard in summer. Don't charge overnight under a pillow. These behaviors expose the battery to combined thermal and electrical stress that accelerates both SEI growth and potential plating.

A phone doing heavy computation (gaming, video recording, navigation) while charging experiences both charging current heat and processor heat simultaneously. Internal temperatures can easily exceed 40°C. The battery management system may throttle charge rate in response, but it can't eliminate the thermal exposure. Better to charge when the phone is idle.

The 80% charge limit helps if your usage pattern allows it. Modern iOS and Android both offer optimized charging features that delay the final portion of charging until just before you typically unplug. These features exist because manufacturers know high-SOC dwell time hurts batteries. The systems learn when you usually disconnect the phone and try to finish charging just before that time, minimizing the hours spent at 100%.

For laptops, the situation is different. Most laptops spend most of their time plugged in, which means calendar aging dominates over cycle aging. A laptop battery that stays at 100% SOC for months loses capacity even without being cycled. The charge limit settings that Lenovo, Dell, ASUS, and others provide (typically allowing limits of 60-80%) can double the useful life of a laptop battery compared to leaving it at 100% continuously.

This is the single most impactful setting most laptop users ignore. A laptop used as a desktop replacement, plugged in 95% of the time, will see its battery degrade primarily from calendar aging at high SOC rather than from cycling. Setting a 60% charge limit eliminates most of this damage. The tradeoff is less runtime when unplugged, but for a machine that rarely leaves the desk, this tradeoff costs nothing.

For electric vehicles, the advice to charge to 80-90% for daily use and save 100% for road trips is sound. The battery management systems in EVs are sophisticated, but they can't fully compensate for extended high-SOC storage. Scheduled departure charging, which completes the charge just before you leave rather than finishing at 2 AM and sitting at 100% until morning, reduces high-SOC dwell time.

Winter charging is where EV owners need to be careful. Preconditioning the battery before charging in cold weather isn't just about comfort. It's about avoiding lithium plating during the charge session. Most EVs with liquid-cooled batteries can manage their own temperature during charging, but the system works better if it starts from a reasonable temperature rather than having to warm up a frozen pack while simultaneously accepting charge current.

Some EV owners go further and limit DC fast charging to occasional road trip use, preferring slower AC charging for daily use. The evidence for this being necessary is mixed. Modern cells with good thermal management tolerate fast charging reasonably well, and the BMS will reduce power as needed to protect the pack. But there's no downside to slower charging if time permits, and the thermal load is undeniably lower.

LFP vs NMC

Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries tolerate abuse better than nickel-rich chemistries. LFP cells can handle more cycles, tolerate higher SOC storage better, and suffer less from high-temperature exposure. The tradeoff is lower energy density (roughly 160 Wh/kg versus 250 Wh/kg for NMC) and worse cold-weather performance.

The durability advantage comes from the chemistry. LFP operates at lower voltage (around 3.2V nominal versus 3.7V for NMC), which means less oxidative stress on the electrolyte and less driving force for parasitic reactions. The olivine crystal structure of LFP is more stable than the layered structure of NMC. No phase transitions occur at high SOC. No oxygen release at high delithiation. No manganese dissolution because there is no manganese.

LFP cells routinely achieve 3000-5000 cycles to 80% capacity under conditions that would kill an NMC cell in 1000-1500 cycles. Calendar aging is slower too.

For applications where longevity matters more than weight or volume, LFP is the better choice. Tesla's switch to LFP for standard-range vehicles reflects this calculation. Energy storage systems almost universally use LFP because a 15-year service life matters more than packing maximum energy into minimum space.

For phones, LFP doesn't make sense. The energy density penalty is too severe for a device that needs to be pocketable. Phones use LCO (lithium cobalt oxide), which has the highest volumetric energy density but also the worst cycle life and thermal stability. This is why phone batteries age faster than EV batteries despite seeing fewer cycles. LCO is fragile. It doesn't tolerate high temperature, high SOC, or high charge rates as gracefully as LFP or even NMC.

Silicon-containing anodes add another layer of complexity. Silicon offers much higher theoretical capacity than graphite (around 4200 mAh/g versus 372 mAh/g), but it expands by 300% during lithiation rather than graphite's 10%. Current commercial cells blend small amounts of silicon into graphite anodes to boost capacity incrementally. The silicon component ages faster than the graphite component, and the blended anodes tend to show steeper capacity fade curves than pure graphite. Devices with silicon-blend anodes benefit even more from shallow cycling because the reduced volume swing extends the silicon's usable life.

Storage

If a device will sit unused for months, discharge it to 40-60% SOC first. Store it somewhere cool but not freezing. Check every few months and top up if it's drifted below 30%.

The 40-60% range minimizes calendar aging while leaving enough margin that self-discharge won't drag the cell into dangerous territory before the next check. Lithium-ion cells self-discharge at roughly 1-2% per month at room temperature, faster when warm. A battery stored at 50% SOC will take over a year to drift into the danger zone below 20%, assuming normal storage conditions.

The worst storage scenario is full charge in a hot environment. A laptop or phone stored at 100% SOC in a garage that hits 40°C in summer will lose significant capacity even without being touched. The combination of high SOC and high temperature is multiplicative. A year of storage under these conditions can cost 20-25% capacity. The same battery at 50% SOC and 20°C might lose 4-5% over the same period.

The second worst scenario is near-zero charge for extended periods. Cells continue to self-discharge during storage, and if SOC drops low enough, the copper anode current collector can start to dissolve. Copper ions migrate to the cathode and deposit there, creating permanent damage. Recovering from deep discharge damage is sometimes possible but never complete. If a cell sits at near-zero SOC for months, expect permanent capacity loss even after recharging.

Some old advice recommends periodically cycling stored batteries to "keep them active." This is wrong. Cycling adds wear. A battery in storage should stay in storage until needed. The only maintenance required is checking SOC every few months and topping up if necessary.

What Doesn't Matter Much

Brand of charger, as long as it meets basic safety standards. A certified third-party charger performs identically to OEM chargers from the battery's perspective. The concern about cheap chargers is real, but it's about electrical safety (fire risk from poor protection circuits) rather than battery degradation. A poorly-built charger might supply unstable voltage or lack proper overcurrent protection, which creates fire risk. It won't cause mysterious battery wear that a good charger wouldn't.

Wireless versus wired charging, mostly. Wireless charging is less efficient and generates more heat, which matters. But the temperature difference is typically 5-10°C, which translates to maybe 50% faster calendar aging during the charging session. For occasional wireless charging, the impact is negligible. For someone who wireless charges overnight every night for years, the cumulative effect might be noticeable. Might. It's not worth losing sleep over.

Exact charge percentage targets. The difference between charging to 80% versus 85% is real but small. The difference between 80% and 100% is much larger. Don't stress about hitting exactly 80%. Being in the right neighborhood is enough. The stress of obsessive monitoring probably causes more harm to the user than the battery gains from hitting exact targets.

Battery calibration is another thing that gets more attention than it deserves. "Calibration" means letting the BMS re-learn the relationship between voltage and actual capacity by occasionally seeing the full SOC range. A full cycle every month or two keeps the fuel gauge accurate. It doesn't restore lost capacity or reverse aging. The battery doesn't need "exercise" or "conditioning." These are myths left over from older chemistries.

Charging overnight every night is fine if the phone has optimized charging enabled. The phone will stop at 80% and finish charging just before your usual wake-up time. If optimized charging is disabled, overnight charging does mean more hours at 100% SOC, which adds calendar aging. But the effect per night is small. Over years, it adds up. Over months, it's hard to measure.

The Real Priority Order

Temperature dominates everything else. A battery kept cool will outlast one kept warm by a factor of two to four, all else being equal. No other single factor has this much influence. Managing temperature during use, charging, and storage is the highest-yield intervention available.

After temperature, SOC management. The hours spent at high charge states accumulate damage steadily through calendar aging. Laptops benefit most from charge limits because they spend so much time plugged in. Phones benefit from optimized charging that avoids overnight 100% dwell time. Storage below 60% SOC rather than at full charge makes a measurable difference over months.

Cycling behavior matters less than the first two factors. Shallow cycles beat deep cycles, but the effect is more modest. The 20-80% SOC window is a reasonable target for daily use. Going somewhat outside this range occasionally isn't catastrophic.

Charge rate matters least among the factors users can control, as long as temperature stays managed. The fear of fast charging is overblown. Cold fast charging is the exception, where plating risk justifies caution.

Batteries are consumables. They degrade no matter what. The goal is not preservation for its own sake but getting good service life without sacrificing too much usability. Someone who keeps their phone at 50% charge to baby the battery has missed the point. The battery exists to power the device, not the other way around.