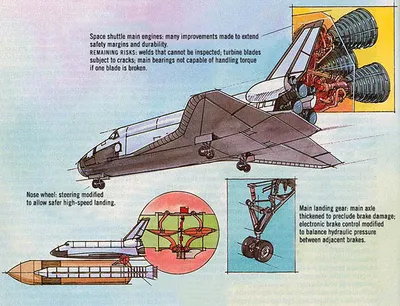

When Ben Einstein tore apart that decommissioned Kiva robot, he found two thermocouples welded beneath the batteries.The Bolt Blog

Four 12V 28Ah lead-acid batteries. Series connection. 48V. Thermocouples welded under the bracket.

The welding is what matters here. Bolting would have been cheaper. Adhesive mounting would have been faster. Welding thermocouples to a battery bracket adds a manufacturing step that somebody had to justify in a cost review meeting. Kiva was a startup burning through venture capital. Every dollar mattered. And yet someone decided that thermal monitoring required the permanence of a weld.

This happened around 2005, possibly earlier. Lithium batteries existed but remained confined to laptops and cell phones. A123 Systems had been founded in 2001 but would not achieve volume production until 2006. The engineers at Kiva were not choosing between lead-acid and lithium. They were choosing lead-acid because lithium was not yet a real option for industrial applications, and then they were figuring out how to make lead-acid work in an application it was never designed for.

The thermocouples were part of that figuring out. Temperature monitoring as a hedge against the unknown. But thermocouples measure temperature; they do not control it. By the time a thermocouple registers a dangerous reading, the electrochemical processes inside the battery have already begun. For lead-acid, this buys time because the failure mode involves gas venting and electrolyte boiling, dramatic but slow. For lithium chemistries, the same monitoring approach would be inadequate. Thermal runaway in lithium cells propagates faster than any human response.

Kiva's engineers seem to have understood this, at least implicitly. The choice of lead-acid and the choice of welded thermocouples form a coherent package: a chemistry with forgiving failure modes paired with monitoring that assumes response time will be available.

What Actually Kills Lead-Acid in AGV Applications

The usual complaints about lead-acid batteries appear in every industry whitepaper comparing battery chemistries: short cycle life, water maintenance, ventilation requirements, low energy density. These complaints are accurate but incomplete.

The failure curve matters more than the cycle count.

A lead-acid battery rated for 1,500 cycles does not deliver 1,500 cycles of gradually declining performance. It delivers perhaps 1,100 cycles of relatively stable performance, then a rapid decline, then failure. The exact timing varies by manufacturer, usage pattern, and maintenance quality, but the shape remains consistent: a plateau followed by a cliff.

For a warehouse robot charging twelve times per day, 350 days per year, this cliff arrives somewhere between month four and month six of operation. Operations planning becomes guesswork. Which robots will fail next week? Which will last another month? The maintenance team cannot know. They can track cycle counts and monitor capacity, but the cliff does not announce itself in advance.

Two responses exist. Conservative operators replace batteries on a fixed schedule, sacrificing 20-30% of theoretical remaining life for predictability. Aggressive operators run batteries until failure, accepting the disruption costs of unplanned downtime. Neither approach is satisfying. The conservative approach wastes money. The aggressive approach wastes time. Both approaches exist because the underlying technology forces a choice between two kinds of waste.

Kiva's 5-minute charge, 1-hour run protocol was an attempt to escape this dilemma. Keeping batteries at high states of charge reduces depth of discharge per cycle, which in theory extends the plateau phase before the cliff.

Whether this actually worked is unclear. Kiva never published reliability data on their battery systems, and Amazon certainly has not published any since the acquisition.

The protocol created its own problems. More frequent charging meant more charging stations, more complex scheduling algorithms, more capital expenditure on infrastructure. Marketing materials presented this as a feature, emphasizing robots that charge quickly and run continuously. The underlying reality was a workaround for battery chemistry limitations.

Why LFP Won

Lithium iron phosphate batteries degrade differently than lead-acid.

The degradation approaches linearity. An LFP cell rated for 4,000 cycles at 80% depth of discharge will show roughly 90% capacity at 1,000 cycles, roughly 82% at 2,000 cycles, roughly 75% at 3,000 cycles. The numbers vary by manufacturer and test conditions, but the shape holds: steady decline rather than plateau-and-cliff.

This predictability changes the maintenance calculus entirely. Operations managers can forecast battery replacements months in advance. Procurement can negotiate volume discounts with lead times. Maintenance windows can be scheduled during low-demand periods. The uncertainty that plagues lead-acid planning largely disappears.

Cycle life comparisons in marketing materials typically focus on the absolute numbers, contrasting 1,500 cycles for lead-acid versus 4,000 for LFP. But a 4,000-cycle battery that fails unpredictably would be worse than a 1,500-cycle battery that fails on schedule. LFP delivers both the higher number and the predictable degradation curve. This combination explains market adoption better than either factor alone.

The thermal stability of LFP adds another dimension. Ternary lithium chemistries such as NMC and NCA offer higher energy density but become increasingly dangerous as they age. Internal resistance rises, heat generation during charging increases, and the margin between normal operation and thermal runaway shrinks. An aged ternary cell is not merely a degraded cell; it is a cell with elevated risk characteristics.

LFP's olivine crystal structure handles aging more gracefully. The phosphate groups hold oxygen atoms more tightly than the oxide structures in ternary cathodes. When things go wrong in a ternary cell, the cathode releases oxygen that feeds combustion. When things go wrong in an LFP cell, the phosphate structure limits oxygen availability. The failure mode is still a failure, but a more contained one.

For a warehouse full of robots carrying aged batteries through narrow aisles lined with merchandise, this containment matters. One battery fire can shut down operations for days. A fleet-wide battery replacement program is expensive but recoverable. The risk asymmetry favors LFP even when the energy density penalty of roughly 30% versus ternary chemistries is considered.

The Lithium Titanate Exception

Baptiste Mauget at Balyo chose lithium titanate. This choice appears in case studies as an example of application-specific battery selection: when cycle life matters more than energy density, LTO makes sense.

The technical argument holds up. LTO can deliver 20,000 to 50,000 cycles depending on operating conditions. The chemistry handles high charge rates, achieving 5C versus 2C for LFP, which means 12-minute charges instead of 30-minute charges. For a robot that charges 24 times per day, these numbers change everything.

LFP: 4,000+ cycles, 2C charge rate, ~30 minute fast charge, higher energy density

LTO: 20,000-50,000 cycles, 5C charge rate, ~12 minute fast charge, ~60% of LFP energy density

Lead-Acid: 1,500 cycles, slow charge, high maintenance, unpredictable failure curve

But Balyo's business model also matters here. The company sells automation retrofits for existing forklift fleets. Their customers already own forklifts, already have lead-acid maintenance procedures, already have charging infrastructure. Convincing a procurement committee to approve a battery technology switch requires a compelling story. "Fifty thousand cycles" is a more compelling number than "four thousand cycles," even if four thousand cycles would be adequate for the application.

LTO's low energy density, roughly 60% of LFP, gets reframed as a benefit in Balyo's marketing: smaller batteries, more compact installations, easier integration with existing equipment. Left unmentioned is that smaller batteries mean more frequent charging, which makes the high cycle count necessary rather than merely impressive.

Mauget stated publicly that LTO was more suitable for his scenario than LFP. He did not say LFP was inadequate. The distinction matters. LFP would probably work fine for most Balyo installations. LTO works fine and provides better marketing differentiation. Both considerations shaped the decision. Pretending otherwise mistakes engineering for pure optimization when it is actually optimization under constraints that include sales and competitive positioning.

The BMS Problem

Battery management systems determine how much of a cell's theoretical capability actually gets used.

An LFP cell rated for 4,000 cycles might deliver 3,500 cycles with an average BMS, 4,200 cycles with an excellent BMS, or 2,800 cycles with a poor one. The BMS controls charging algorithms, balances cells within the pack, estimates state of charge, predicts remaining useful life, and triggers protective shutdowns when parameters exceed safe thresholds. Every one of these functions affects real-world performance.

Cell balancing alone can swing pack lifespan by 20% or more. A pack with 16 cells in series will inevitably develop capacity mismatches as individual cells age at slightly different rates. Without active balancing, the weakest cell limits the entire pack. Charging must stop when the weakest cell reaches voltage limits, even if other cells could accept more energy. With effective balancing, energy redistributes from stronger cells to weaker ones, and the pack ages as a unit rather than as a collection of individuals with the worst individual dictating outcomes.

Procurement decisions rarely account for BMS quality. RFQ documents specify cell chemistry, capacity, cycle life, and price. BMS capabilities might appear as a line item such as "includes battery management system" without detail on algorithm sophistication or component quality. Suppliers competing on price have every incentive to minimize BMS cost, which means minimizing BMS capability.

The result is a market where the visible specifications look similar across suppliers while the invisible factors vary dramatically. Two battery packs with identical spec sheets can deliver 30% different real-world performance. The customer who bought on price discovers this difference over years of operation, by which time the purchasing decision has long since been finalized and the procurement manager has moved on to other projects.

Amazon operates at a scale where these differences compound into serious money. A million-robot fleet replacing batteries every two years cycles through 500,000 battery packs annually. A BMS optimization that extends pack life by 5% avoids 25,000 replacements per year. At reasonable cost estimates, this means tens of millions of dollars in avoided procurement and maintenance costs. Amazon has the data, the engineering resources, and the financial motivation to develop custom BMS rather than accepting commodity solutions.

Whether they have actually done so remains unknown. The operational details of Amazon Robotics are closely held. But the incentives point strongly toward significant BMS investment, and the silence about battery suppliers suggests something beyond standard commercial confidentiality.

Charging Infrastructure and Queuing Theory

Standard guidance suggests one charging station per five to eight robots. The ratio varies by supplier and application but falls consistently in this range.

Queuing mathematics complicate this simple ratio.

Adding charging capacity produces diminishing returns. Going from one station per eight robots to one station per four robots roughly halves average wait times. Going from one station per four robots to one station per two robots produces a much smaller improvement. Going from one station per two robots to one station per one robot produces almost no improvement at all while doubling infrastructure cost.

The asymmetry arises from queue dynamics. With sparse charging infrastructure, robots frequently arrive at occupied stations and must wait. With moderate infrastructure, robots usually find available stations. With dense infrastructure, most stations sit idle most of the time. The waiting-time curve has a knee somewhere in the middle range, and optimizing infrastructure spend means finding that knee rather than simply adding capacity.

Complicating this further: optimal charging density depends on battery chemistry. Frequent shallow charges benefit LFP because the chemistry tolerates partial charging well, and frequent shallow charges harm lead-acid because partial charging accelerates sulfation. A warehouse designed around lead-acid charging patterns with fewer stations, deeper discharges, and fuller charges operates suboptimally when switched to LFP. The infrastructure that made sense for one chemistry becomes wrong for another.

Most warehouses do not redesign charging infrastructure when they change battery chemistry. The stations remain where they were installed. The robots follow the same routes. Only the batteries change, leaving a mismatch between infrastructure assumptions and battery characteristics. The resulting inefficiency is invisible unless someone runs the analysis to quantify it, which rarely happens because the analysis requires operational data that most organizations do not collect systematically.

Thermal Management Done Wrong

Most AGV battery packs address thermal management through ventilation slots and temperature sensors. When temperature exceeds thresholds, charging current decreases or charging stops entirely. This prevents thermal runaway but does nothing for optimization.

Temperature affects LFP performance substantially. Below 10°C, charging capability drops sharply, and some cells cannot safely accept charge at all near freezing. Above 45°C, aging accelerates significantly. The optimal band runs from roughly 25°C to 35°C, which happens to match comfortable human working temperatures but not necessarily warehouse conditions.

A warehouse in Phoenix operates at different thermal conditions than a warehouse in Minneapolis. The same battery pack behaves differently in each location. Yet battery specifications assume some nominal operating temperature, typically 25°C, that may never occur in actual deployment.

Cell-to-cell temperature variation within a pack creates another problem. Cells near the motor controller run hotter than cells near the chassis exterior. Over thousands of cycles, this temperature differential produces capacity differentials.

After two years of operation, a 16-cell pack might contain cells ranging from 95% original capacity to 75% original capacity, depending purely on thermal position. The pack's usable capacity reflects the weakest cell, meaning 25% of the theoretical capacity has been lost not to chemistry but to thermal design.

Addressing this requires either active thermal management, which adds cost and complexity, or careful pack design that equalizes cell temperatures, which adds engineering time that becomes difficult to justify against commodity battery pack pricing. Neither solution appears in most AGV battery packs because neither solution improves the visible specifications that drive purchasing decisions.

Why Kiva Really Chose Lead-Acid

Mick Mountz founded Kiva in 2003. Lithium iron phosphate existed as a laboratory curiosity. A123 Systems had been founded but had not yet shipped commercial products. BYD was still primarily making mobile phone batteries. CATL did not exist.

The choice was not between lead-acid and LFP. The choice was between lead-acid and the various lithium chemistries available in 2003, none of which had established supply chains for industrial applications, safety certifications for warehouse environments, or track records in heavy-duty cycling.

A startup with limited engineering resources cannot simultaneously develop a novel warehouse robotics system and establish a lithium battery supply chain from scratch. Mountz needed batteries that worked, that could be sourced reliably, that could be integrated without specialized expertise. Lead-acid met those requirements. Lithium might have been better in the abstract but was not available in the concrete.

Mountz had worked at Webvan before founding Kiva. Webvan built elaborate conveyor-based fulfillment infrastructure, spent $830 million, and went bankrupt in 2001. The lesson was clear: fixed infrastructure scales poorly and fails expensively. Mobile robots offered flexibility that conveyors could not match, provided the robots actually worked.

The battery decision in this context was not about optimization. It was about risk management. Choosing lead-acid meant choosing a technology that definitely worked, even if suboptimally, over a technology that might work better but might also not work at all. The thermocouples welded beneath those batteries suggest that even with the safe choice, Kiva's engineers were not entirely confident about what would happen under sustained heavy use.

By 2012, when Amazon acquired Kiva for $775 million, the lithium landscape had changed entirely. LFP cells were available from multiple suppliers at reasonable prices with established safety records. The engineering problems that had made lithium impractical in 2003 had been solved. Whether Amazon switched the Kiva fleet to LFP immediately, gradually, or never remains unclear.

What Amazon Knows and Will Not Say

Amazon operates over a million warehouse robots. The battery chemistry powering these robots has not been publicly disclosed.

Lead-acid at this scale would leave traces. Water maintenance for a million battery packs requires either an army of maintenance technicians or an automated water-filling system, both of which would be visible in hiring patterns, supplier relationships, or patent filings. Ventilation requirements for lead-acid charging would affect warehouse HVAC design, which would appear in building permits and construction contracts. Acid spill procedures would appear in OSHA documentation.

If Amazon still uses lead-acid, they have done an impressive job hiding the operational footprint. If they have switched to lithium, they have declined numerous opportunities to publicize the environmental and efficiency benefits. Both possibilities raise questions that Amazon has chosen not to answer.

One possibility: the fleet uses mixed chemistries. Newly manufactured robots receive LFP packs while legacy robots retain lead-acid until scheduled replacement. A multi-year transition would explain both the absence of a clean switch announcement and the absence of visible lead-acid infrastructure at scale.

Another possibility: different facilities use different batteries based on local conditions. A warehouse in a mild climate might use LFP, which tolerates a wide temperature range. A warehouse in extreme heat might use LTO, which handles thermal stress better. A warehouse operating legacy equipment might retain lead-acid for compatibility. Managing this complexity would require significant engineering resources, which Amazon possesses.

The silence suggests that battery strategy provides competitive advantage worth protecting. Cells are commodities, as CATL, BYD, Gotion, and EVE all make adequate LFP cells, but the integration details are not commodities. BMS algorithms tuned to specific operating patterns, thermal management designed for specific facility conditions, charging schedules optimized for specific electricity tariffs: these details compound into meaningful efficiency differences at million-unit scale.

Several battery suppliers list Amazon as a customer on their websites. Amazon has not confirmed these relationships. The asymmetry, with suppliers wanting to claim Amazon while Amazon remains unwilling to claim suppliers, suggests the valuable intellectual property resides not in the cells but in everything surrounding them.

Degraded Batteries and Missing Markets

Electric vehicle batteries enjoy a developed secondary market. A battery too degraded for vehicle use, typically below 80% capacity, can serve in stationary storage applications where energy density matters less. Companies collect, test, grade, and resell used EV batteries. The supply chain exists because the volume justifies it: hundreds of GWh retire from vehicle service annually.

AGV batteries lack equivalent secondary markets. Global annual retirement volume probably amounts to a few GWh, distributed across thousands of warehouses using dozens of different form factors. The logistics cost of collecting, testing, and reselling these batteries exceeds their residual value. A retired AGV battery pack typically goes directly to recycling or, worse, to landfill.

LFP batteries contain no cobalt. Cobalt creates the most severe recycling challenges among battery materials. It has high value, creating incentive for informal recycling with poor environmental controls. It has supply chain human rights concerns, creating reputation risk for end users. It has chemical complexity, creating technical challenges for recovery. A cobalt-free chemistry avoids these issues.

This missing secondary market distorts procurement economics. Purchase decisions focus on initial price and expected cycle life. Disposal costs, including hazardous waste handling, transportation, and documentation, receive less attention because they appear years later in different budget categories. Future environmental liabilities receive even less attention because their probability and magnitude remain uncertain.

A procurement decision optimizing for next quarter's budget might reasonably choose a cheaper battery regardless of disposal implications. A procurement decision optimizing for five-year total cost would weight disposal more heavily. A procurement decision accounting for regulatory and reputation risk over a ten-year horizon would weight cobalt-free chemistry heavily. Most procurement decisions optimize for next quarter.

Numbers Worth Tracking

Supplier spec sheets report cycle life, energy density, charge rate, calendar life. These numbers permit comparison across products but miss the metrics that actually determine operational value.

Electricity cost per thousand tasks captures system efficiency comprehensively. The number integrates battery round-trip efficiency measuring energy lost to heat during charge and discharge, charging strategy efficiency comparing full charges versus opportunity charges, scheduling efficiency examining whether robots travel empty to reach chargers, and tariff optimization assessing whether charging occurs during low-price periods. A well-designed system might show 30% lower electricity cost than a poorly designed system using identical batteries.

| Metric | What It Measures | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity cost per 1,000 tasks | Round-trip efficiency, charging strategy, scheduling, tariff optimization | 30% variance possible between systems using identical batteries |

| Unplanned downtime % | Reliability across scheduling, order flow, labor allocation | Disruption costs exceed replacement battery costs by 10x or more |

| 5-year TCO / Year 1 CapEx | Hidden ongoing costs vs. initial investment | Lead-acid: 4-5x ratio; LFP with proper management: 2-2.5x ratio |

Unplanned downtime percentage captures reliability comprehensively. A battery pack that fails unexpectedly disrupts more than one robot. It disrupts the scheduling system, the order flow, the labor allocation. The cost of unplanned downtime exceeds the cost of the replacement battery by an order of magnitude or more. A battery system optimized for cost that produces more unplanned downtime may cost more overall than a premium system with better predictability.

Five-year total cost of ownership divided by first-year capital cost reveals the magnitude of hidden costs. A ratio of 2 means ongoing costs equal initial investment. A ratio of 4 means ongoing costs triple initial investment. Lead-acid systems with their maintenance requirements and frequent replacements typically show ratios of 4-5. LFP systems with proper thermal management and appropriate charging infrastructure can achieve ratios of 2-2.5. The difference between 2 and 4 represents a 50% reduction in total cost, invisible at procurement but dominant over the asset's lifetime.

These metrics require operational data collection and analysis that most organizations do not perform. The data exists in principle through charge logs, maintenance records, and downtime reports, but often lives in disconnected systems that nobody has integrated. The result is procurement decisions made on incomplete information, repeated across thousands of warehouses, compounding into industry-wide inefficiency.

Those Welded Thermocouples

Einstein's teardown photos show thermocouples welded beneath the battery bracket. The navigation system received detailed analysis. The mechanical structure received detailed analysis. The battery installation received a paragraph.

Batteries are infrastructure. They enable the interesting parts of the system without being interesting themselves. The same teardown dynamic applies to the industry more broadly: presentations at logistics conferences feature navigation algorithms and picking optimization and labor savings, while battery selection appears as a line item in implementation budgets.

Those welded thermocouples represent a decision somebody made in 2004 or 2005. Not just the decision to monitor temperature, as that part is obvious, but the decision that monitoring mattered enough to warrant welding rather than bolting or gluing. The decision that even with lead-acid, even with its relatively forgiving failure modes, thermal management deserved the permanence and reliability of a welded connection.

Whether this caution was justified remains unknown. Perhaps the thermocouples triggered alarms that prevented incidents, and those incidents left no record because they were prevented. Perhaps they never triggered at all, and the welding was unnecessary expense. Perhaps they triggered frequently, and the Kiva operations team developed extensive protocols for managing thermal events, protocols that Amazon has since replaced or refined or discarded.

The absence of public information does not mean the absence of events. It means the absence of records, or the absence of access to records, or the decision by those with access to keep the information private. Amazon now operates the largest fleet of warehouse robots ever assembled. Whatever has been learned about battery failure modes in that fleet, and something has surely been learned because a million robots over a decade generate countless opportunities for learning, remains within Amazon.

The industry would benefit from that learning being shared. It will not be shared, because competitive advantage comes partly from knowing things that competitors do not know. So each warehouse operator relearns the same lessons, makes the same mistakes, discovers the same problems that Amazon discovered and solved years ago.

Those thermocouples welded beneath the batteries were the beginning of a knowledge accumulation process that continues today, invisibly, inside Amazon's operational data systems. The rest of the industry operates in partial darkness, guided by supplier specifications and limited operational experience, unable to access the largest dataset on warehouse robot battery behavior ever collected.

Good engineering often produces the result that nothing happens. The thermocouple triggers, the charging stops, the battery cools, operations continue. No incident report, no news article, no teardown revealing the near-miss. The counterfactual, meaning what would have happened without the thermocouple, remains forever hypothetical. Success in safety engineering is invisible by design.