Industrial Technology

What voltage lithium battery is best for a forklift?

Marcus Chen

December 19, 2025

Match the battery voltage to the forklift. A 48V forklift takes a 48V battery. An 80V forklift takes an 80V battery. Drop a 60V pack into a 48V machine and the controller either shuts down or burns out.

That much is obvious. The questions that actually matter are different. Which voltage tier makes sense when specifying new equipment. Whether consolidating a mixed fleet around one platform pencils out financially. Whether that 48V unit purchased in 2016 can handle the throughput increase planned for next quarter without burning through contactors. The voltage number stamped on a forklift battery shapes current flow, component temperatures, and service life. It determines how much electricity moves pallets versus how much heats up copper wiring. These are not small differences.

Lead-acid chemistry set these standards. One lead-acid cell puts out around 2 volts. Twelve cells wired in series make 24V. Twenty-four cells make 48V. Forty cells make 80V. Nothing deliberate about these targets. Just electrochemistry artifacts that became entrenched through decades of repetition across the industry.

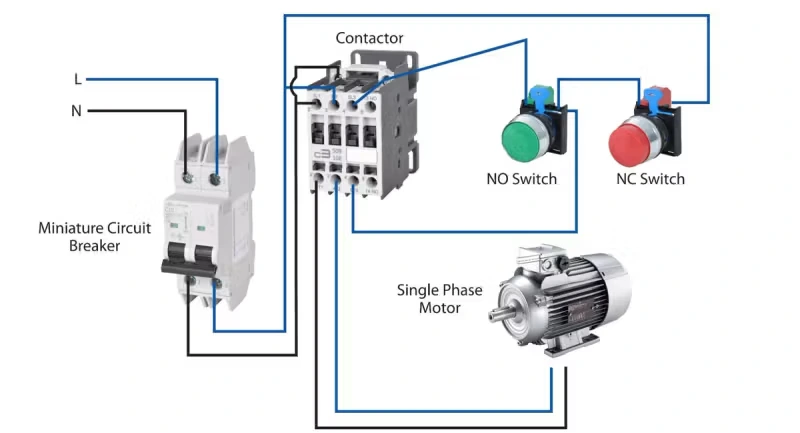

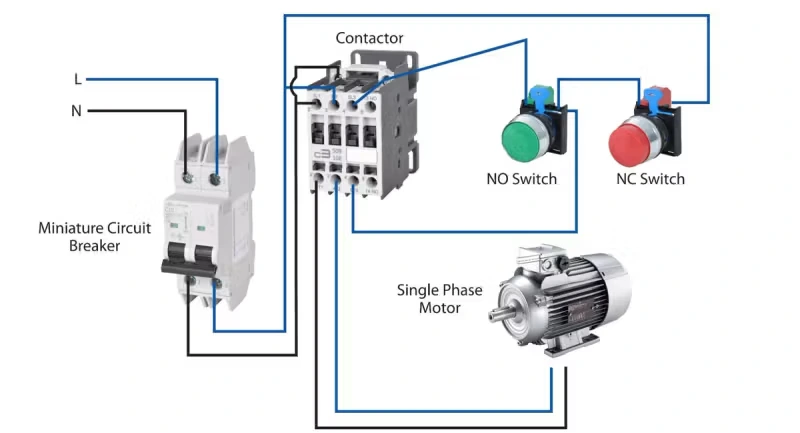

Motor designs, controller architectures, contactor ratings, charger specs—everything was built around these voltage levels starting in the 1950s and 1960s. Billions of dollars of installed equipment accumulated. Tooling. Supply chains. Three generations of forklift mechanics trained on these systems. When lithium battery manufacturers started entering the forklift market around 2010, they faced an obvious choice: design packs that drop into existing equipment, or convince the entire industry to redesign everything. Nobody picked option two.

Lithium iron phosphate cells run at 3.2V nominal. Eight cells produce 25.6V, close enough for 24V equipment. Fifteen cells hit 48V. Sixteen cells reach 51.2V, slightly high for 48V systems but manageable if the controller tolerates the overvoltage. Twenty-five cells get to 80V.

The chemistry mismatch creates problems after installation. A 48V lead-acid pack swings between roughly 42V when depleted and 52V when full. A 48V lithium pack swings between 40V and 58V. That extra 6 volts at full charge confuses equipment designed for narrower parameters. Controllers throw overvoltage faults when they see 58V. Chargers designed for lead-acid assume the battery is full at 52V and stop there, leaving 15–20% of capacity unused.

Power equals voltage times current. A 15kW motor demand can be satisfied at different points along that curve.

Current Draw at Different Voltage Levels

At 24V: around 625 amps.

At 48V: around 312 amps.

At 80V: roughly 187 amps.

Heat scales with the square of current. The 24V system at 625 amps generates about eleven times more resistive heating than the 80V system at 187 amps while performing identical mechanical work. That factor of eleven comes from the I²R relationship. Double the current, quadruple the heat. Triple the current, nine times the heat. The numbers get punishing fast.

Every wire, connector, and contactor in the power path contributes to thermal load

Every wire, connector, contactor, and transistor in the power path contributes to this heating. Anderson connectors get warm. Terminal lugs get warm. The BMS shunt resistor gets warm. That thermal energy ends up in cable insulation, contactor housings, controller heat sinks, battery cells. Damage accumulates invisibly while the forklift keeps running. Then three major components fail within a two-month window, and the maintenance team starts asking questions that should have been asked during procurement. By then the equipment is out of warranty and the battery vendor has moved on to the next sale.

The efficiency angle rarely comes up during purchasing. Every watt that becomes heat instead of motion is wasted electricity. Two power bills running in parallel: one for work, one for warming the warehouse.

Toyota builds the 6BWC and 8BWC walkie pallet jacks on 24V. Crown runs 24V on the WP series. Raymond uses 24V on the 8210 and 8410 pallet trucks. These machines are designed for a specific duty cycle: grab a pallet, travel 30 meters, set it down, wait. Short bursts with cooling gaps between tasks.

A 24V system pulling 10kW draws north of 400 amps. Cable rated for continuous 400A duty needs 70–95mm² cross section depending on run length and ambient conditions. Contactors at that current rating cost two to three times what 200A units cost.

When pallet jacks operate within design parameters, 24V causes no problems. Intermittent duty protects the electrical system. Problems start when operations push equipment past intended limits. A distribution center running 24V walkie stackers through continuous two-shift operation sees very different outcomes than a warehouse where the same units sit idle between tasks. The two-shift machines never cool down. Temperatures climb through the shift and stay there. Everything ages faster.

The failure pattern at facilities overstressing 24V equipment follows a remarkably consistent arc. Year one: no problems. Year two: contactors sticking. Controller fault codes appearing. Battery capacity dropping faster than cycle count would explain.

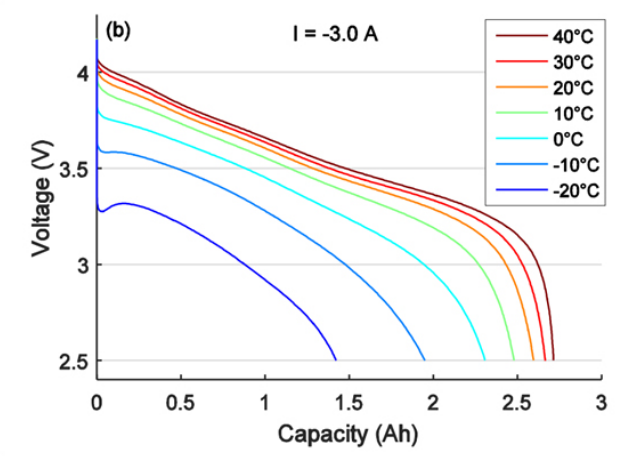

Cold storage makes everything worse. Lithium cells shed 20–30% capacity below minus 10°C. A 24V pack sized with 10% margin at room temperature cannot absorb that hit. Equipment dies mid-shift in the freezer aisle. Product sits. Shipping deadlines slip. Ramps create similar problems. Sustained incline operation demands high torque for extended periods—not the short bursts the design assumes. A walkie stacker rated for flat floors has no business on a loading dock with a grade.

A facility in Memphis learned this the hard way after converting their entire walkie stacker fleet to 24V lithium to save on battery costs. Eighteen months later, half the contactors had been replaced. The maintenance manager who approved the purchase was no longer with the company. 24V works for pallet jacks and light stackers doing intermittent duty on level surfaces at moderate temperatures. Push beyond those boundaries and the math turns ugly fast.

Linde builds the E14 through E20 counterbalance trucks on 48V. The E25 through E35 step up to 80V. That split at roughly 2.5 tons reflects engineering calculations about where the electrical architecture starts fighting the workload.

Toyota runs 48V on the 8FBE sit-downs, the 8FBMT and 8FBN reach trucks, most of the order picker line. Hyster and Yale share a common 48V electrical platform across Class I and Class II up to 3 tons. Useful for facilities running both brands, since contactors, controllers, and electrical components interchange. Crown uses 48V on FC and RC reach trucks and the SC counterbalance series. Jungheinrich does the same on EFG series up to 3 tons.

The numbers work out at this level. A 48V reach truck lifting 2 tons pulls 250–300 amps during the lift. Standard industrial contactors and controllers handle that without stress. A 300A contactor running at 250A lasts for years. Run that same contactor at 400A and expect months.

Two-shift operations pair well with opportunity charging at 48V. Plug in during breaks, plug in at lunch, and the pack never drops below 30% state of charge. Lithium cells thrive in that middle range. A 48V pack on this regime can push 3500–4000 cycles before capacity fades to 80%. Three shifts changes the math. Equipment runs hot for 16–20 hours with only brief charging windows. Five-year components become three-year components. Some operations accept that accelerated wear. Others spec 80V for heaviest-use equipment and reserve 48V for lighter applications.

Above 3 tons or 8 meters of lift, cracks start to show. A 4-ton lift to 9 meters might pull 25–30kW peak. At 48V, that translates to over 500 amps surging through the system. Spec sheets say the forklift can handle it. Running that load all day, every day pushes contactors and controllers toward thermal ceilings. Shutdowns multiply. Unplanned downtime creeps up.

The actual ceiling for 48V depends more on duty cycle than on rated capacity. A 48V truck rated at 3.5 tons, spending most of its time moving 2-ton pallets with occasional heavy loads, will hold up fine. The same truck moving 3.5 tons continuously will not.

Linde and Still both use 80V on heavy counterbalance lines. Linde E60 through E80. Still RX60-60 through RX60-80. Jungheinrich EFG 535–550. The pattern holds across European manufacturers. Interesting footnote: Still and Linde are both owned by KION Group, which explains why their electrical architectures align so closely. Parts compatibility between the two brands at matching voltage tiers is better than most dealers will admit publicly.

BYD came to market with lithium-native designs and no lead-acid legacy to accommodate. They landed on 72V for heavy counterbalance models. The performance difference between 72V and 80V amounts to roughly 10% in current draw for equivalent power output. Operationally insignificant. Fleet compatibility should drive the decision. A facility running 80V Linde equipment has no business adding 72V BYD units and managing two charger inventories. The procurement savings on the BYD unit disappear into charger costs and inventory complexity within two years.

Heavy-duty operations above 3 tons demand higher voltage architectures to manage current loads effectively.

The physics case for high voltage gets stronger as loads climb. Repeated 5-ton lifts to 8–10 meters demand sustained power around 35–40kW. At 48V, delivering 40kW requires over 800 amps through the system. Cables rated for continuous 800A duty are expensive, heavy, and a routing nightmare. The cable bends alone become a headache—800A cable does not flex easily, and forklift battery compartments were not designed with that cable diameter in mind. Contactors at that rating cost as much as economy cars and still wear out fast. At 80V, the same 40kW draws 500 amps. Smaller cables. Smaller contactors. Heat load cut by more than half. Equipment that would cook itself at 48V runs without drama at 80V.

Three-shift heavy operations need 72V or 80V. No exceptions, regardless of what the procurement budget says. A 48V truck rated for 4 tons, running 4 tons across three shifts, follows a predictable trajectory: acceptable performance for roughly a year, maintenance costs climbing in year two, major overhaul or replacement by year three. The upfront battery savings get eaten by repair invoices and downtime. A food distribution center in Ontario ran the numbers after going through this cycle twice. The 80V replacement fleet cost 15% more than the 48V units they replaced. Five years later, total cost of ownership was 22% lower. The difference came from maintenance labor, parts, and avoided downtime during peak shipping seasons.

Cold storage with heavy pallets compounds problems. Minus 20°C strips 30–40% of lithium capacity. Heavy loads demand high current. Continuous operation prevents recovery time. Stack all three conditions and 48V cannot cope.

An 80V system absorbs the cold penalty while keeping current manageable. Outdoor applications with sustained travel—distribution yards, intermodal facilities—also favor high voltage. A forklift covering ground at 15 km/h for ten hours draws substantial current for propulsion alone. Add lifting and the total climbs. An 80V platform handles the combination where 48V struggles.

Retrofits look attractive on paper. Skip the cost of new equipment, capture lithium benefits on existing assets. Execution determines whether that works out.

The voltage curve mismatch creates problems immediately. A 48V lithium pack charges to 58V and discharges to 40V. Lead-acid equipment assumes 52V at the top, 42V at the bottom. Lead-acid chargers may terminate at 52V, stranding 20% of the lithium pack's capacity. Operators complain the new battery runs shorter shifts than the old one. The battery works fine; the charger is wrong. Replacing chargers adds cost that should have been in the original project budget but somehow never was.

Lead-acid controllers may throw overvoltage faults when they see 58V from a fully charged lithium pack. The forklift refuses to start, or cuts out shortly after. Technicians chase phantom electrical faults for weeks until someone figures out the controller needs different parameters. Controllers built after 2015 usually have lithium configuration options buried in their firmware. Getting to them requires dealer diagnostic equipment. Changing them requires training most in-house teams lack. Some dealers charge $400–600 per unit for this service. Others refuse to support conversions on equipment they did not sell.

Counterbalance considerations become critical when retrofitting lighter lithium packs into equipment designed for heavier lead-acid batteries.

The counterweight issue catches buyers who skipped physics class. Counterbalance forklifts use the battery as ballast. A 48V lead-acid pack runs 1200–1500 kg. A 48V lithium pack with equivalent energy storage runs 400–600 kg. That 800 kg gap shifts the center of gravity forward. A properly ballasted forklift lifts rated load to rated height with margin. Remove 800 kg and rated load at rated height risks tip-over. The nameplate becomes fiction. OSHA does not accept "the battery vendor said it would be fine" as an explanation.

Good conversion kits from BYD, CATL, and better third-party integrators include steel ballast plates. Total mass matches the original lead-acid pack. Balance preserved. Nameplate accurate. Cheap kits skip the ballast, marketing the weight reduction as a benefit. The problem surfaces when a forklift tips forward under a load it handled safely with lead-acid. A logistics company in New Jersey discovered this the hard way with a pallet of bottled water. No injuries, but $30,000 in damaged product and a near-miss investigation that consumed two weeks of management time.

BMS integration determines whether the fuel gauge means anything. Without proper communication between battery management system and forklift controller, the dashboard lies. Shows full at half charge. Shows empty with 30% remaining. Operators learn to ignore it and run until the BMS forces a protective shutdown mid-task without warning. Integrated correctly, the BMS feeds real state-of-charge to the controller. The gauge tracks reality. Charging behaves predictably. Fault codes correlate with actual faults. The difference between "works" and "works correctly" is substantial.

Electrical losses from undersized voltage never show up on any single invoice. They scatter across line items, departments, and fiscal years until the connection disappears.

A 48V system drawing 300 amps through cables and connections with maybe 10 milliohms total resistance dumps 900 watts into heat. An 80V system delivering equivalent mechanical work draws 180 amps and loses around 324 watts. Nearly 600 watts of difference, continuously, under load. Across an 8-hour shift at 60% utilization, that adds up to something like 2.8 kWh per forklift. Multiply by 250 working days and one forklift wastes roughly 700 kWh annually from the current-heat relationship alone. A twenty-unit fleet: north of 13,000 kWh.

Annual Energy Loss Comparison

Industrial electricity runs anywhere from eight cents to fifteen cents per kWh depending on region and rate structure. Annual waste somewhere in the $1,000 to $2,000 range in direct charges. That excludes secondary effects—accelerated component wear, more frequent maintenance, shortened equipment life. Nobody runs these calculations at purchase. Battery vendors quote sticker price. Utility bills lump all loads together. Maintenance logs record failures without tracing causes.

Operations that actually track total cost of ownership at the equipment level see patterns that others miss. An 80V fleet costs more upfront. Per operating hour across a ten-year span, it costs less than an equivalent 48V fleet doing heavy work. The crossover point varies with utilization and electricity prices, but for three-shift operations the 80V investment typically breaks even by year four. After that, the 80V fleet generates savings every month it runs.

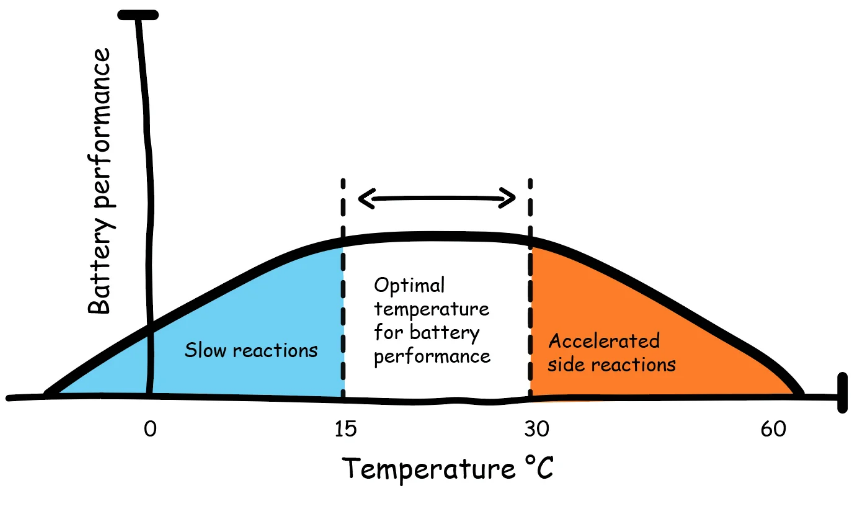

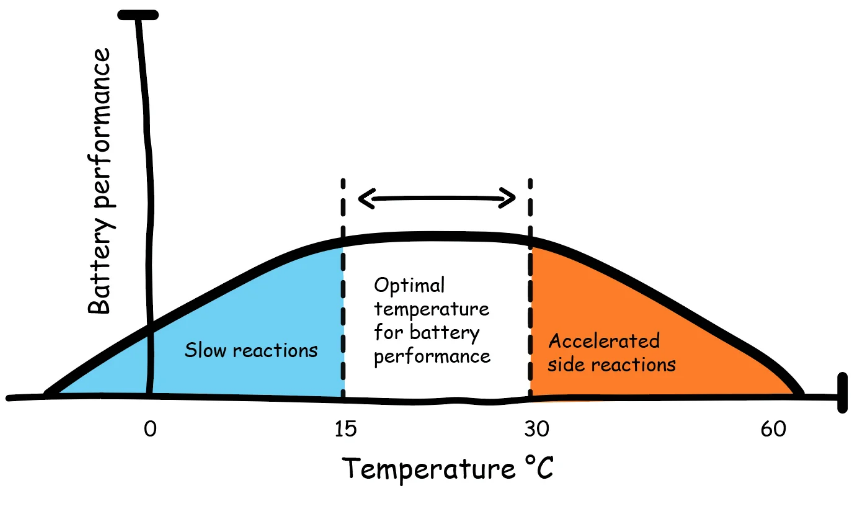

Lithium chemistry has strong opinions about operating temperature.

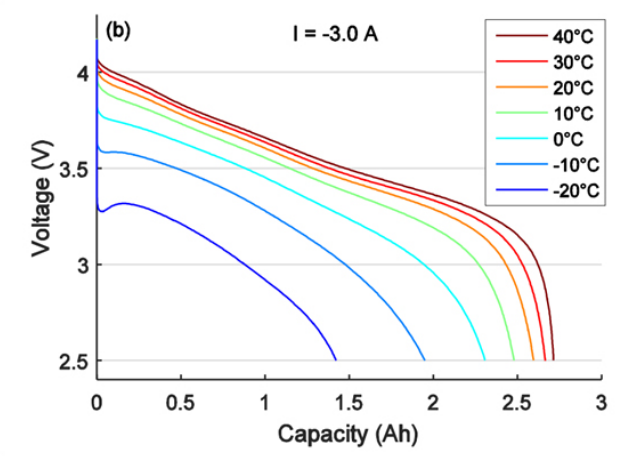

Cold cuts capacity immediately. A lithium pack at minus 10°C delivers roughly 80% of room-temperature rating. Minus 20°C: somewhere in the 65–70% range. Minus 30°C: closer to 55–60%. Cells still function—shift length shrinks. A cold storage facility near Green Bay sized their 48V fleet for 6.5-hour coverage based on room temperature testing. First winter, the third shift ran out of battery before the shift ran out of work. The solution involved buying two additional spare packs at $18,000 each and installing warming circuits in the charging stations. Should have spec'd 80V from the start.

Higher voltage provides margin. An 80V system losing 30% capacity still delivers enough current for heavy lifting without straining components. A 48V system sized tight at 20°C becomes inadequate in the freezer. Current climbs to compensate for reduced voltage. Heat rises. All the symptoms of an overstressed system emerge, except now they emerge in an environment where everything already runs harder.

Heat works differently. A pack running at 45°C internal temperature delivers rated power without complaint. No immediate capacity loss. Damage accumulates silently—heat accelerates side reactions that degrade lithium cells over time. A battery cycling at 45°C ages at roughly double the rate of one cycling at 25°C. This is not theory. Cell manufacturers publish these curves. Most buyers never ask to see them.

Higher voltage helps indirectly by reducing resistive heating in cables and connections. The pack runs cooler under load.

Ambient temperature remains uncontrollable. Phoenix warehouses hit 40°C inside during summer. Dubai yards hit 50°C. Equipment in these environments faces accelerated aging regardless of voltage tier. Opportunity charging to keep state of charge in the middle range helps—avoiding the stress peaks at either end of the charge cycle extends life somewhat. But hot is hot.

Multiple voltage tiers compound complexity. The compounding accelerates over time.

A facility running 24V pallet jacks, 48V reach trucks, and 80V counterbalance units needs three charger types. Spares for each. Dedicated charging stations for each. Technician training on three electrical architectures. Parts inventory spanning three platforms. Mistakes scale with complexity. A night-shift worker plugging a 48V forklift into an 80V charger destroys the battery pack. The charger pushes voltage past BMS limits. Cells enter thermal runaway. The pack vents—possibly ignites—definitely needs replacement. Labels and procedures help. Tired workers make mistakes regardless.

The simplest structure: two voltage tiers. Use 48V for equipment under 3 tons and for reach trucks and order pickers. Use 80V for heavy counterbalance above 3 tons. Avoid 24V except for genuinely intermittent light-duty pallet jacks.

Spare pack inventory at multiple voltage tiers ties up capital and floor space. A facility stocking one spare per tier across three tiers has more money immobilized in batteries than a two-tier facility with one spare per tier. Operations without spares wait for replacements when packs fail. Shifts lost while units ship.

Skip 36V entirely—that platform offers nothing over 48V except another charger type and another parts bin.

New facilities start clean. Pick two tiers, buy accordingly, install matching chargers, train technicians on two architectures. Lock the standard before the first unit arrives. Existing facilities inherit legacy decisions. A distribution center accumulating 24V, 36V, 48V, and 72V equipment over two decades cannot standardize overnight. The path is gradual replacement: as equipment ages out, replace at target voltage tiers. Five to ten years, the fleet converges.

Resist adding voltage tiers for niche applications. Short-term optimization creates long-term complexity. A 36V reach truck fitting one specific use case perfectly adds a fourth charger type, fourth parts bin, fourth training requirement. The niche benefit rarely exceeds system cost.

Toyota material handling standardized on 48V across most of the warehouse lineup. 8FBE sit-downs. 8FBMT multi-directional reach trucks. 8FBN narrow-aisle reach trucks. 8FBP order pickers. Facilities committing to Toyota inherit 48V standardization as a side effect. Heavy counterbalance trucks in the 8FB series above 3.5 tons step to 80V. Linde draws the line around 2.5 to 3 tons.

Crown complicates standardization decisions. FC reach trucks ship in 36V, 48V, and 72V variants depending on model and capacity. SC counterbalance follows a similar spread. Facilities running Crown equipment face harder choices because the product line does not naturally push toward two tiers. Crown dealers will argue this provides flexibility. Fleet managers will argue it creates chaos.

Strategic platform selection at the manufacturer level can simplify or complicate long-term fleet standardization efforts.

Hyster-Yale runs 48V and 80V platforms across both brands. Mixed Hyster and Yale fleets at matching voltage tiers benefit from parts interchange—contactors, controllers, chargers swap between brands. The two brands compete in the market but share engineering underneath. Knowing this saves money.

BYD Forklift arrived with lithium-first designs, no lead-acid heritage. The 72V platform on heavy trucks draws slightly less current than 80V competitors at equivalent output. Service network density and parts availability lag established brands. Hangcha and Heli follow the 48V/80V pattern. Service support varies regionally—strong dealer networks deliver value, thin coverage means waiting.

The pattern that produces regret: procurement specifies minimum voltage tier meeting rated capacity on paper, selects lowest-priced battery meeting that specification, ships equipment to operations. Operations then spends the next three years managing a forklift running at thermal limits during normal work.

A 48V forklift rated for 3.5 tons can lift 3.5 tons. Spec sheet confirms it. But spec sheets assume duty cycles with recovery periods between tasks. Continuous 3.5-ton lifting through two shifts exceeds design assumptions. By year two, maintenance owns a chronic headache. The procurement team that signed off on the purchase has moved on to other projects.

Overbuilding wastes money differently. An 80V forklift for an application peaking at 2 tons on single shift costs more upfront, more for chargers, more for parts. Excess capacity sits unused. A 48V unit would have handled the job at lower total cost. The challenge is knowing which scenario applies before the equipment arrives.

Critical Pre-Purchase Questions

Getting voltage right requires understanding actual operating conditions. Peak loads matter less than typical loads. Questions that need answers before purchasing: What do pallets actually weigh on a normal day? What is the usual lift height? How many lifts per hour? How many shifts per day? Temperature range across seasons? Sustained travel or short hops?

A facility moving 1.5-ton pallets to 6 meters on two shifts needs fundamentally different equipment than one moving 3-ton pallets to 10 meters on three shifts. Both procurement teams might evaluate 48V counterbalance forklifts. Only one should buy them.

For pallet jacks and small walkie stackers on single shifts, flat floors, loads under 1.5 tons, moderate temperatures—24V handles it. Keep 24V equipment out of freezers, off ramps, away from multi-shift schedules. Anything that violates those constraints will generate repair tickets.

The 48V sweet spot covers counterbalance forklifts up to 3 tons, reach trucks up to 8 meters, order pickers, two shifts with opportunity charging. Watch utilization rates. Equipment running continuously without natural breaks wears faster than equipment with gaps between tasks. A forklift that spends 40% of its shift parked while operators handle paperwork or wait for product ages very differently than one running continuously.

Above 3 tons on counterbalance, above 8 meters on reach trucks, three-shift operations, cold storage below minus 10°C, outdoor yards with sustained travel: 72V or 80V, depending on what the preferred manufacturer offers. The upfront premium returns through lower operating costs and extended equipment life.

36V should be skipped unless inheriting equipment that cannot yet be replaced. The platform fragments infrastructure without offering anything 48V cannot provide. Every 36V unit in a fleet is a charger type and a parts bin that serves one purpose.

New facilities should commit to 48V and 80V from day one. Lock the standard before purchasing the first unit. Existing facilities can consolidate incrementally as equipment reaches end of life. Push back on pressure to add voltage tiers for niche applications. The niche never stays a niche—it becomes a legacy constraint.

Conversions require budgeting for the complete scope: controller reconfiguration, charger compatibility, BMS integration, counterweight ballast. Cut-rate kits missing any of these elements produce problems costing more than the savings. The cheap path costs more. It always costs more.