Can golf carts be equipped with 36-volt lithium batteries?

Twelve LiFePO4 cells wired in series. 3.2V nominal per cell, 38.4V total. Works with legacy 36V drive systems without modification.

That 3.2V figure sits at the midpoint of the discharge curve. Working voltage per cell runs 2.5V to 3.65V. Multiply by twelve and the pack voltage swings between 30V and 43.8V across its usable capacity. Lead-acid systems only vary about 6V between full and empty states.

LiFePO4 chemistry produces a flat discharge curve. Voltage drops from full charge, plateaus through roughly 80% of capacity, then falls sharply near depletion. Lead-acid voltage sags from the moment discharge begins and keeps sagging. A lithium cart accelerates the same on hole eighteen as hole one. Lead-acid carts feel strongest right after charging. By the back nine, acceleration has noticeably weakened. Most operators notice this behavioral difference before they notice anything about cycle life or weight reduction.

Why 36V Became Standard

Six 6-volt lead-acid batteries cost less than eight. Economics, not engineering.

Higher voltage systems perform better. Power equals voltage times current. A cart drawing 3-5kW for hill climbing pulls 80-140A at 36V. At 48V, current drops to 60-105A. Lower current allows thinner conductors, smaller connectors, reduced heat generation in the BMS power stage.

Resistive losses scale with the square of current. Double the current, quadruple the waste heat.

Lithium pack pricing tracks total energy capacity rather than cell count. The cost argument for 36V disappeared when the chemistry changed. Converting existing 36V vehicles to 48V requires replacing motor, controller, and wiring harness. Parts run $800-1500 before labor. Hard to justify on vehicles already in service. 36V lithium exists as an upgrade path for legacy vehicle owners.

BMS

BMS quality determines whether the pack survives long enough to deliver its rated capacity. Buyers focus on cell specifications and ignore the BMS entirely.

A BMS monitors twelve individual cells. Prevents overcharge, over-discharge, overcurrent, thermal abuse. A $50 BMS and a $200 BMS both claim identical functionality. The $50 unit cuts corners on component ratings, temperature sensing, balancing capability. These compromises only reveal themselves after months of service or during the first genuinely demanding operating condition.

Cell Variation

Manufacturing tolerances produce 2-3% capacity variation within a single production batch. Internal resistance varies too.

These differences compound. Lower-capacity cells reach voltage limits first during both charging and discharging. Pack capacity becomes limited by the weakest cell. One cell at 95% capacity means a 95% capacity pack.

Cell-to-cell differences increase with cycling. They do not average out.

Balancing

Passive balancing dissipates excess energy as heat when any cell exceeds a threshold voltage during charging. Balancing currents run 50-200mA. Simple. Cheap. A pack with 5% cell imbalance needs dozens of complete charge cycles before passive balancing catches up.

Chronic partial charging creates a problem. Unplugging before reaching 100% prevents passive balancing from ever engaging. Cell divergence accelerates.

Active balancing transfers energy between cells rather than wasting it. Works during both charging and discharging. Balancing currents hit 1-2A or higher. Appears in packs above $500.

Specification sheets avoid clear terminology. Check balancing current. Under 200mA indicates passive. Over 1A indicates active. No balancing current listed means the manufacturer prefers silence on this point.

| Passive | Active | |

|---|---|---|

| Current | 50-200mA | 1-2A+ |

| Method | Dissipates as heat | Transfers between cells |

| When active | Charging only | Charging & discharging |

| Recovery (5% imbalance) | Dozens of cycles | A few cycles |

Low-Temperature Charging

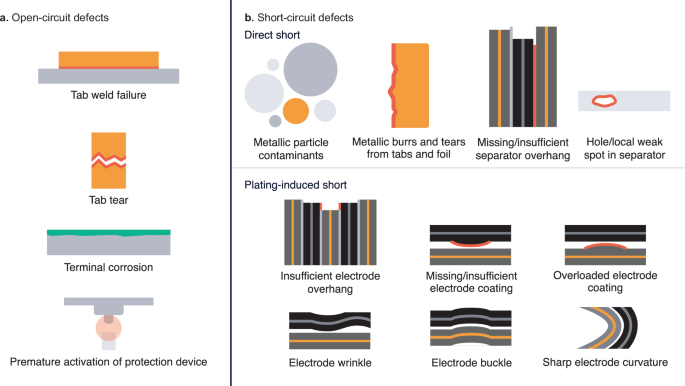

Charging lithium cells below 0°C causes permanent damage. Lithium metal plates onto the anode surface, forming dendrites. Dendrites penetrate the separator between anode and cathode, creating internal shorts. Capacity drops permanently. In severe cases, the pack catches fire.

Some manufacturers claim their cells tolerate cold charging. The electrochemistry says otherwise.

Adequate BMS designs lock out charging below safe temperatures. Better designs include heating elements that warm cells before accepting charge.

Temperature sensing implementation varies wildly. Budget units mount a single thermistor on the circuit board rather than on the cells themselves. The board reads 10°C while cells sit at -5°C. No protection value whatsoever.

Cart stored outdoors in freezing weather overnight. Charger connected first thing in the morning. Exactly the conditions that cause dendrite formation. Damage accumulates invisibly. Capacity degradation appears only after significant harm has already occurred.

Cold climate installations require BMS units with temperature sensors mounted on cells and charging lockout thresholds set appropriately. Storing vehicles indoors during winter provides additional margin.

Charging

Using the old charger after a lithium retrofit ranks among the most common mistakes. Lead-acid chargers do not work with lithium. Incompatible. The problems show up immediately: incomplete charging, BMS protection trips, permanent cell damage.

Lead-acid charging algorithms push voltage to 44-46V during equalization phases. This design feature helps break down lead sulfate crystals that form on plates during discharge. Lithium cells have no such crystals and no tolerance for such voltages. Triggers overvoltage protection on packs with competent BMS design. Damages cells directly on packs without adequate protection.

Float charging creates a separate problem. Lead-acid chargers maintain float voltage indefinitely after reaching full charge, compensating for lead-acid's relatively high self-discharge rate. Lithium self-discharges at 1-3% per month. Float charging serves no purpose and keeps cells at elevated voltage states. Calendar aging accelerates independent of cycling.

A lithium pack left connected to a lead-acid charger for months ages faster than one stored at partial charge with no charger attached. The charger actively harms the battery it intends to maintain.

Lithium chargers terminate at 43.2V or 43.8V for 12S LiFePO4 configurations. Output ceases entirely after reaching full charge. No float phase.

Charger selection involves two specifications. Cutoff voltage must match pack chemistry: 43.2V or 43.8V for LiFePO4, not the 44-46V that lead-acid algorithms target. Charging current determines duration: 10A requires roughly 10 hours for a 100Ah pack, 20A halves that time. Currents up to 0.2C impose minimal stress on quality cells. Higher currents accelerate charging but increase thermal stress.

Specification Reality

Cycle Life

Published figures come from laboratory conditions: constant 25°C, controlled charge and discharge rates, full depth-of-discharge cycles, adequate rest periods.

Field service looks nothing like this.

Summer charging in a non-climate-controlled garage exposes cells to 40°C ambient. Winter storage drops temperatures toward freezing. Charging follows irregular schedules. Carts sit unused for weeks during off-season at various states of charge. Acceleration and hill climbing demand current spikes that lab protocols avoid.

A pack rated 2000 cycles under test conditions delivers 800-1200 cycles in actual golf cart service. Still exceeds lead-acid cycle life by a factor of three or four. But falls well short of headline numbers.

Capacity

Specifications reference either total cell capacity or usable capacity after BMS reserves. A 100Ah pack with conservative BMS voltage cutoffs delivers 90Ah usable.

Some suppliers commit outright fraud. Packs contain cells rejected from primary production. Cells salvaged from decommissioned equipment with unknown cycle history. Cells that simply do not match specifications. A "100Ah" label on a pack that delivers 75-80Ah.

Run a complete discharge at known load upon receipt. Measure actual amp-hours delivered. Catches fraud before the return window closes.

Drop-in Claims

Marketing language overstates installation simplicity.

Dimensional differences require mounting modifications or adapter brackets. Terminal positioning differs from lead-acid, necessitating cable rerouting. The weight reduction creates its own problem: hardware designed to secure 180 pounds of lead-acid batteries does not adequately restrain 60 pounds of lithium.

Factory state-of-charge gauges become useless. Lead-acid voltage correlates with remaining capacity. Lithium voltage stays nearly constant through most of discharge, then drops rapidly near empty. Gauges calibrated for one chemistry give misleading readings with the other.

"Drop-in" means "fits in the same space." Not "requires no modifications."

Budget Products

36V 100Ah packs occasionally appear under $400.

The math does not work. Quality LiFePO4 cells from established manufacturers cost $80-120 per cell at wholesale volumes. Twelve cells run $960-1440 before adding BMS, enclosure, wiring, assembly labor, shipping. A $400 pack cannot contain quality cells and a competent BMS. Something has been compromised.

Manufacturing rejects that failed QC testing at primary production facilities end up in secondary markets. Higher internal resistance, lower capacity, inconsistent performance. Cells recovered from decommissioned equipment carry unknown cycle wear and calendar aging. BMS implementations omit temperature sensing, minimize balancing, set inappropriate current limits.

Safety certifications require testing fees and engineering resources. Budget manufacturers skip the testing and print the certification marks anyway. UL, CE, FCC logos on a product do not guarantee the product actually passed those certifications.

Warranty terms prove unenforceable. The company does not exist when claims arise. Or ignores them. Or requires shipping the 50-pound battery pack to China at owner expense.

Thermal runaway remains uncommon even among cheap products. When it happens, consequences extend beyond battery replacement. Vehicle damage. Structure fires. Property loss. A $400 battery that burns down a garage costs more than a $1,800 battery that does not.

The price range reflects genuine differences in component quality and manufacturing standards, not just branding. Lead-acid fails in predictable ways. Budget lithium failures escalate rapidly when they occur.

Selection Criteria

LiFePO4, not NMC. NMC saves roughly 20% on weight for equivalent capacity. Thermal stability drops. Golf carts charge unattended overnight in garages attached to houses. The weight savings do not justify the fire risk.

Discharge current specifications need scrutiny. Continuous ratings below 150A indicate an undersized BMS power stage. Peak ratings should exceed 300A. Acceleration up a steep hill with two passengers and loaded bag compartment pulls serious current. A BMS that trips protection during normal operation defeats its own purpose.

Some manufacturers list only continuous ratings. Peak current capability has been left off the sheet for a reason.

Bluetooth phone connectivity has become standard on mid-range packs. Apps display individual cell voltages: twelve separate readings that should stay within 0.05V of each other on a healthy pack. Voltage drift between cells over time indicates balancing problems or failing cells. Catching these early prevents sudden capacity loss.

Temperature protection for cold climates should be verified directly with suppliers rather than assumed from specification sheets. Ask specifically: where are the temperature sensors mounted, and at what temperature does the BMS lock out charging? Vague answers suggest the manufacturer has not thought carefully about this.

Warranty terms signal confidence. Below five years suggests either uncertainty about product longevity or a business model built on customers forgetting about warranties before exercising them.

Self-Assembly

Building from cells and aftermarket BMS units cuts costs 30-50% versus commercial packs. The savings attract hobbyists and fleet operators alike.

Required competencies include high-current electrical work: spot welding or bolted bus bar connections between cells, proper torque specifications for bolted connections, BMS wiring and configuration, insulation techniques to prevent shorts. Mistakes with 100+ amp-hour lithium cells carry consequences beyond ruined components.

Cell sourcing presents its own challenges. Genuine cells from established manufacturers cost more than cells of uncertain origin. Savings from cheap cells translate to reduced capacity, shorter life, or safety problems that eliminate any cost advantage. Grade A cells from reputable suppliers run $80-100 each. Grade B cells cost less but deliver less. These are often manufacturing seconds or cells that sat in warehouses too long.

Assembly errors create expensive lessons. Cells damaged by improper spot welding cannot be returned. Inadequate insulation causes shorts that destroy cells or start fires. Improper BMS configuration permits abuse conditions that degrade cells faster than normal use.

The learning curve involves wrecked cells and wasted money before producing a functional pack. Builders with electrical background and proper equipment can make self-assembly work. Builders without that background spend more on mistakes than a commercial pack costs.