Marcus Chen

Senior Energy Systems Engineer

December 18, 2025

28 min read

What is 24V Lithium Battery?

That whole 24V versus 12V argument got settled sometime in the last two years, and most people missed it. Go look at what Victron released in 2024. Go look at Battle Born's product lineup changes. The manufacturers have voted with their engineering budgets, and 24V won.

Modern LiFePO4 battery cells powering the next generation of mobile and off-grid energy systems

A 24 volt lithium battery is eight LiFePO4 cells in series. 3.2 volts each, times eight, gives you 25.6V nominal. Simple arithmetic.

The interesting part is why this particular voltage won out over everything else. Not 12V. Not 48V. Not the 20V that some Chinese manufacturers tried pushing a few years back. 24V.

Current is the reason. Or more specifically, heat. Run a 2000 watt load at 12 volts and you're pulling 167 amps. At 24 volts, 83 amps. Cable heat scales with current squared. Squared. That's not a subtle difference. A wire carrying 167 amps gets four times hotter than the same wire carrying 83 amps. Touch a battery cable after running a big inverter load on a 12V system sometime. You'll understand.

Why 24V Specifically

Some people argue for 48V. On paper, the efficiency argument gets even better at higher voltage. Half the current again. But 48V creates problems that 24V doesn't have. OSHA considers 50V the threshold for electrical hazard in wet conditions. Coast Guard regulations get complicated above certain voltages. Insurance companies ask more questions. The extra paperwork and safety requirements eat up whatever efficiency you gained.

12V made sense when lead-acid was the only option and typical loads were a few lights and a radio. That world is gone. People want air conditioning in their RVs. They want electric trolling motors that run all day. They want to go a week without plugging in. The loads grew the 12V infrastructure stayed the same, and now it's hitting its limits.

Cable connections for high-current battery systems

Look at the cable runs in a typical boat or RV installation. Battery bank in the back, inverter somewhere in the middle, loads all over. Twenty feet of cable isn't unusual. At 12V and 100 amps, you need cable thick enough to moor a ship if you want acceptable voltage drop. At 24V and 50 amps for the same power, the cable costs drop by more than half and the installation stops requiring a gorilla to wrestle the wires into place.

Component availability sealed the deal. In 2019, finding a quality 24V inverter-charger meant paying a premium for Victron or Magnum. Now Aims, Growatt, EG4, and a dozen others offer 24V models at competitive prices. The economy of scale kicked in. When speccing systems now, 24V components are sometimes cheaper than 12V equivalents with the same power rating.

The Chemistry Part

LiFePO4 is lithium iron phosphate. Different from the lithium in your phone. The phone uses some variant of lithium cobalt oxide or NMC, designed to stuff maximum energy into minimum space. Nobody cares if a phone battery lasts two years because you're buying a new phone anyway.

LiFePO4 takes the opposite approach. The olivine crystal structure is stupid stable. Iron doesn't want to go anywhere. The phosphate backbone holds together through thousands of cycles. You sacrifice energy density for longevity. A phone battery at 250 Wh/kg versus LiFePO4 at maybe 110 Wh/kg. For something you carry in your pocket, that matters. For something bolted into a boat that never moves, who cares?

Cycle life numbers that get thrown around vary wildly. Vendors claim 10,000 cycles. Lab tests have shown failure at 2,500. The truth depends on how hard you run them, how hot they get, and how good the manufacturing was. EVE and CATL cells from their A-grade production lines hit 4,000+ cycles reliably. The mystery cells some Amazon sellers package into batteries might die at half that.

Thermal stability matters more than most people realize. LiFePO4 doesn't have thermal runaway in any meaningful sense. You can nail-penetrate a cell and it gets hot but doesn't explode. Try that with a laptop battery and you get a fire. This is why LiFePO4 can go in an engine compartment or under a bed without making insurance companies nervous.

Voltage Behavior Through the Charge Cycle

Discharge curves are weird if you're coming from lead-acid. LiFePO4 sits at almost the same voltage from 90% state of charge down to about 20%. Then it falls off a cliff. A fully charged 24V pack reads around 27.6V. At 50% it reads maybe 26.4V. At 20% still around 25.6V. At 10% it's dropping fast toward the low voltage cutoff.

⚡

Nominal Voltage

25.6V nominal from eight 3.2V LiFePO4 cells in series, providing optimal balance between safety regulations and system efficiency.

🔋

Charging Voltage

28.4V standard charge (3.55V/cell) or 29.2V max (3.65V/cell). Lower voltage extends cycle life by 20-30% with only 5% capacity trade-off.

♻️

Cycle Life

Quality cells from EVE and CATL achieve 4,000+ cycles. Cycle life depends on depth of discharge, temperature management, and cell quality.

A flat discharge curve is both a feature and a problem. Feature because your loads see stable voltage for most of the battery capacity. Problem because you can't just look at a voltmeter and know how full the battery is. With lead-acid you could estimate state of charge from resting voltage with maybe 10% accuracy. With LiFePO4 you need coulomb counting or you're guessing.

Charging is straightforward. Constant current until the pack hits about 28.4V (3.55V per cell), then constant voltage until current tapers to some cutoff threshold. Some people charge to 29.2V (3.65V per cell) for maximum capacity. Others stop at 28.0V (3.5V per cell) for maximum longevity. The difference in usable capacity is maybe 5%. The difference in cycle life might be 20-30%.

What Actually Breaks

BMS failures kill more battery packs than cell failures. A battery management system monitors cell voltages, handles balancing, and provides protection against overcharge, overdischarge, and overcurrent. A good BMS costs maybe $80 in quantity. A cheap BMS costs $15. Guess which one most budget battery brands use.

Balancing matters particularly for series cells. Manufacturing variation means no two cells have exactly the same capacity. Over time, the slightly smaller cell becomes the limit. Without balancing, it hits low voltage cutoff while the other cells still have capacity left. The pack looks dead even though most of the energy remains trapped in the other cells.

Passive balancing bleeds off the high cells through resistors. Slow and wastes energy as heat. Active balancing moves charge from high cells to low cells. Faster and more efficient but more expensive and complex. Most consumer-grade packs use passive balancing at maybe 100mA. Industrial packs might do 2A active balancing. The difference shows up when cells drift apart.

Critical Safety Warning

Connection failures account for most field problems. A BMS can be perfect, cells can be perfect, and a bad crimp or corroded terminal will still burn your boat down. High current connections accumulate damage from thermal cycling. Each load cycle heats the connection, it expands, cools, contracts. Eventually the crimp loosens or the contact resistance rises enough to generate more heat than it can dissipate. Connectors melt. It happens.

Torque specs exist for a reason. Battery terminals that say "tighten to 80 in-lb" mean it. Over-torquing crushes the terminal and creates a weak point. Under-torquing leaves a loose connection that arcs. Neither ends well.

Heat cycling deserves more attention than it gets. Batteries that charge and discharge daily experience significant temperature swings in their connections. Each swing stresses the crimp joint. After a few thousand cycles, the copper work-hardens and the crimp loosens. Annual inspection and retorquing prevents failures. Most people skip this until something melts.

Water intrusion kills batteries in ways that aren't always obvious. A splash on the BMS board might not cause immediate failure, but corrosion develops over months. The next spring the battery refuses to charge and nobody remembers that it got wet last summer. Sealed enclosures with proper IP ratings prevent this. Cheap battery cases with snap-fit lids don't.

Real World: Marine Use

Trolling motors are the killer app for 24V lithium. A 36V trolling motor on three lead-acid batteries weighs somewhere around 180 pounds. The same runtime in LiFePO4 weighs maybe 70 pounds. Put 110 pounds of weight savings in the bow of a 16-foot bass boat. The handling difference is obvious.

Marine applications benefit significantly from lithium's weight savings

RV owners increasingly adopt 24V systems for extended off-grid capability

36V is three 12V batteries in series, which means you could also do two 24V batteries for 48V systems or keep a single 24V pack for the growing number of 24V motors. Minn Kota and MotorGuide both expanded their 24V motor lines recently.

Charging on boats is trickier than RVs. Shore power is easy. Running a proper lithium charger off the engine alternator is not. Stock alternators use internal regulation tuned for lead-acid. The absorption voltage is wrong. The charge current tapering is wrong. Some alternators will work. Some will overheat trying to push current into a battery that keeps accepting it. An external regulator like a Wakespeed or Balmar MC-614 solves this.

Cranking batteries remain lead-acid in most marine applications. An LiFePO4 cranking battery exists and works, but the cost premium is hard to justify for something that just needs to deliver 800 amps for three seconds twice a day. House bank goes lithium. Cranking bank stays AGM.

Corrosion is the marine reality. Every connection will eventually corrode unless you prevent it. Dielectric grease on every terminal. Heat shrink over every connection. Inspect annually and replace anything questionable. The salt air finds any weakness.

Boat wiring runs are usually longer than RV installations and more exposed to moisture. A center console fishing boat might have batteries in the stern, electronics at the helm, and a trolling motor on the bow. That's potentially 20+ feet of cable run for the main power distribution. At 24V and 100A, 4 AWG handles the run with acceptable drop. At 12V and 200A for the same power, you need 4/0 or bigger. Good luck routing that through a boat's cable runs.

Bilge pump and navigation light circuits usually stay 12V even in a 24V conversion. These are safety-critical loads that need to work even if the main DC-DC converter fails. A small secondary 12V battery, maybe just a 20Ah lithium pack, dedicated to safety loads provides redundancy. Connect it to the main bank through a small combiner or isolator so it stays charged during normal operation but can power lights and bilge independently.

Dual battery setups for separating house and starting banks have been standard practice for decades. The traditional approach uses an isolator or ACR between two 12V banks. Converting to 24V house with 12V start requires rethinking this. One approach: keep the 12V starting battery completely isolated, charged by the engine alternator through its original circuit, while the 24V house bank runs through a separate DC-DC charger from the alternator. Another approach: run a small 12V battery in parallel with the 24V bank's DC-DC converter output, letting the house bank charging system maintain the starting battery.

Fish finders and chart plotters draw more power than people expect, especially the big screen units. A 12-inch display pulling 40 watts doesn't sound like much until you run it eight hours. That's 320 watt-hours, or about 13Ah from a 24V bank. Add radar at 25 watts, a VHF on standby at 5 watts, stereo at 30 watts, and livewells pumping at 15 watts and you're looking at 100+ watts of baseline electronics load before anyone touches a trolling motor or runs the anchor windlass.

Real World: RV Use

A typical RV electrical system is an archaeological dig of previous owners' modifications. Original converter from 2008, someone's solar addition from 2015, a bigger inverter from 2019, and now you want to convert to lithium.

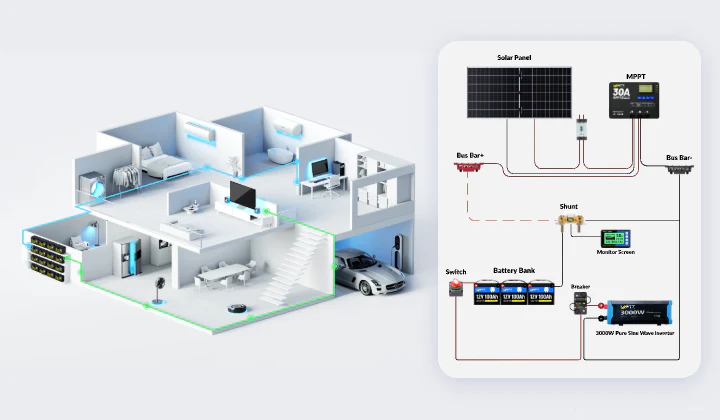

Most conversions keep the 12V distribution intact and just swap the battery bank. The factory wiring for lights, water pump, furnace fans, and slides stays at 12V. A DC-DC converter steps 24V from the new battery bank down to 12V for those loads. The big loads - air conditioning, induction cooktop, microwave - run through the inverter.

Important Consideration

One gotcha is the factory converter/charger. It expects a 12V lead-acid battery. It will try to charge your 24V lithium pack at 12V, which does nothing at best and damages something at worst. The factory unit either gets bypassed, replaced, or fed from the DC-DC converter output. Each approach has tradeoffs.

Progressive Dynamics and WFCO make 12V converters that have lithium charge profiles. They're designed to charge 12V lithium directly. If you want to keep a 12V system but upgrade to lithium batteries, these are the easy path.

A full 24V conversion replaces the battery bank with 24V lithium, adds a 24V inverter-charger for AC loads and shore charging, adds a 24V-to-12V DC-DC converter for house loads, and adds a 24V solar charge controller. That's $3,000-5,000 in components before installation. The payoff is a coherent system that can run air conditioning off batteries for hours instead of minutes.

Slide-out motors are one of the trickiest loads for lithium conversions. They're designed for 12V and draw huge current for short periods. A slide motor might pull 150 amps for 30 seconds. At 24V with a DC-DC converter in the path, that converter needs to be rated for the surge. Most 30A DC-DC converters will fold when the slides move. Size the converter for peak load, not average load. Or install a small 12V AGM battery specifically for the slides, maintained by a trickle charge from the DC-DC output.

Air conditioner runtime is what sells most people on lithium. A rooftop AC unit pulls about 1200-1500 watts running, 2500+ watts starting. A 3000W inverter handles it. Running the AC requires about 60Ah per hour from a 24V bank.

Propane refrigerator conversions to residential 120V models have become popular in the full-time RV community. The Dometic or Norcold propane fridge sucks propane at alarming rates and doesn't work great in hot weather anyway. A residential fridge runs on AC from the inverter and pulls maybe 40 watts average. Over 24 hours that's about 1kWh, or 42Ah from a 24V bank. A 200Ah 24V pack can run a fridge for multiple days without sun, which the propane fridge couldn't do anyway when the coach isn't level.

Air conditioner runtime is what sells most people on lithium. A rooftop AC unit pulls about 1200-1500 watts running, 2500+ watts starting. A 3000W inverter handles it. Running the AC requires about 60Ah per hour from a 24V bank. A 400Ah bank gets you six hours of AC, more than enough to cool down during the afternoon heat and sleep comfortably. Lead-acid couldn't do this. The discharge rate would have killed the batteries in a season.

Inverter placement matters more than people realize. The cable between battery and inverter carries the full current, which at 3000W from a 24V bank is 125 amps. Every foot of cable adds resistance and heat. Keep the inverter within six feet of the batteries if possible. Use the gauge the inverter manufacturer specifies, not what some random forum post suggests. Undersized inverter cables are the number one cause of voltage drop complaints.

Solar on RV roofs faces constraints that ground-mounted systems don't. Roof space is limited. Shade from AC units, antennas, and vent covers blocks portions of panels. Air circulation under panels is poor, so they run hot and produce less than their rating. Expect 70-80% of rated output on a good day. A 400W rooftop array might actually produce 300W at noon in summer. Size accordingly.

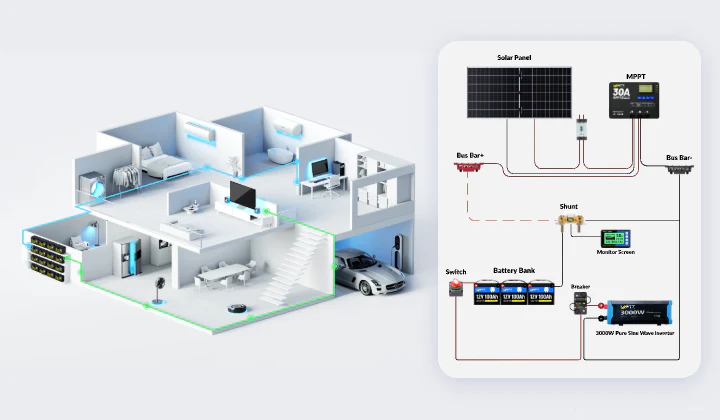

Real World: Solar

Off-grid solar with battery storage lives or dies on system efficiency. Every percentage point matters when you're trying to make it through three cloudy days.

A 24V battery bank matches well with typical solar array voltages. Two standard 40V-open-circuit panels in series gives you 80V to the charge controller input. MPPT conversion to 24V battery voltage runs around 97-98% efficient. The same array feeding a 12V bank runs slightly less efficiently because the conversion ratio is larger.

Modern solar arrays paired with 24V lithium storage provide reliable off-grid power

Panel configuration affects performance in partial shade. Two panels in series means one shaded panel tanks the whole string. Two panels in parallel lets the unshaded panel continue near full output while the shaded one contributes what it can. The tradeoff is lower voltage and higher current, which means bigger wire gauge and potentially lower MPPT efficiency. There's no perfect answer.

Battery bank sizing for off-grid requires calculating daily energy use, desired days of autonomy, and acceptable depth of discharge. A house using 4kWh per day that wants three days autonomy at 50% depth of discharge needs 24kWh of storage. At 24V that's 1000Ah, typically configured as four 24V 300Ah batteries in parallel or some similar arrangement.

Paralleling batteries creates its own challenges. Each battery needs to contribute proportionally to the current. If one battery has slightly lower internal resistance, it carries more than its share of the load and ages faster. Quality batteries from the same production batch minimize this variation. Mixing different ages or brands is asking for trouble.

Wire sizing for off-grid systems scales fast. A 3kW solar array at 100V input voltage draws 30A. You need 2 AWG or bigger for any reasonable run length. Ground-mounted arrays 50 or 100 feet from the battery shed require serious cable investment. Some builders run high-voltage DC from the array to a charge controller located near the batteries, minimizing the heavy cable runs.

MPPT charge controller selection involves current rating, but also input voltage range. Input voltage range matters - not all controllers handle the high voltage that three or four panels in series produce in cold weather. Software features matter - adjustable absorption time, temperature compensation, and programmable float voltage extend battery life. Communication protocols matter - does it talk to your battery monitor? Your inverter? Your remote monitoring system?

Victron equipment has become the de facto standard for off-grid solar because everything talks to everything else. The SmartSolar charge controllers, MultiPlus inverters, Cerbo GX monitoring, and compatible battery BMS all share data over a common bus. The system knows the battery state of charge, adjusts charging accordingly, and logs everything for troubleshooting.

Ground mount versus roof mount is a bigger decision than it first appears. Ground mounting allows optimal tilt angle, easy cleaning, and simple expansion. Roof mounting saves yard space, keeps panels out of reach, and requires no separate structure. The practical difference in energy production can be 10-20% depending on roof pitch and orientation. A south-facing roof at 30 degrees is close to optimal for most North American locations. An east-facing flat roof might only capture 70% of available energy.

Snow shedding from ground-mounted panels at steep angles happens naturally. Snow on low-angle or flat panels can block production for days. In snowy climates, steeper mounting angles and clear access for manual clearing improve winter performance. Some off-grid users in northern areas simply oversize their systems to compensate for winter losses rather than fighting the snow.

Panel degradation runs about 0.5% per year for quality silicon panels. A 400W panel produces 380W after ten years, 360W after twenty. System sizing should account for this. Oversizing by 10-15% initially maintains adequate production as panels age. The cost difference is minimal compared to coming up short on cloudy winter days a decade from now.

The BMS Details

A battery management system does more than protect against abuse. A good BMS provides telemetry that helps diagnose problems before they become failures.

Cell-level voltage monitoring reveals imbalances early. If one cell consistently reads 50mV lower than the others, that cell is aging faster or was weaker from manufacturing. Catching this early means you can add supplemental balancing or replace the cell before it limits the pack.

Temperature monitoring prevents charging below safe limits. LiFePO4 should not be charged below about 32°F. The lithium plates out as metal on the anode instead of intercalating into the graphite structure. Plated lithium is permanently lost capacity plus a potential safety hazard. Cold-weather BMS units either refuse to charge below temperature threshold or enable heating circuits to warm the pack first.

Bluetooth connectivity has become standard on better BMS units. Checking cell voltages with a phone app beats crawling under a bed with a multimeter. Daly, JBD, Overkill, and JK all offer app-connected BMS options in the $100-200 range.

Current sensing accuracy matters for state of charge estimation. If the BMS thinks you pulled 50Ah you actually pulled 55Ah, the state of charge display will drift increasingly wrong. Eventually it says 30% remaining when the battery is actually empty. The trip current sensor requires calibration and periodic verification.

Communication protocols for system integration are still a mess. Victron has VE.Can and VE.Direct. Growatt has their proprietary thing. EG4 has another thing. Getting the BMS, inverter, and solar controller to all talk to each other and coordinate their behavior requires matching brands or dealing with translation devices that may or may not work reliably. The industry needs a standard and doesn't have one.

High-side versus low-side BMS placement affects system design. High-side BMS installs between the positive cell terminal and the positive battery output. Low-side installs on the negative side. High-side allows measuring true cell voltages directly. Low-side is simpler but adds the BMS shunt resistance to voltage measurements. For most applications this doesn't matter. For precision state-of-charge tracking it might.

What To Actually Buy

Cell quality hierarchy roughly goes: EVE, CATL, Lishen, Gotion at the top. Unknown cells from unknown factories at the bottom. The cells inside a finished battery pack are usually not disclosed. Brands like Battle Born, Victron, and RELiON use quality cells but charge accordingly. Brands like Chins, Lossigy, and Ampere Time use whoever gives them the best price that month.

Buying cells and building your own pack saves money and lets you pick exactly what goes inside. A set of eight EVE 304Ah cells runs around $800-1000. Add a $150 BMS, a $50 case, and your time crimping bus bars. The finished pack has maybe $1200 in parts and competes with commercial units at $2500-3000.

DIY has a downside though: support. When the commercial pack fails under warranty, you get a replacement. When your DIY pack fails, you get to diagnose which component died and replace it yourself. For people comfortable with electrical work, this is fine. For people who want something that just works, pay the premium for a finished product with a warranty.

Amp-hour ratings inflate on cheap batteries. A battery marked 200Ah that actually delivers 170Ah is stealing 15% of what you paid for. The only way to know is to test - discharge at a known rate and measure actual capacity. BMS telemetry helps here. Reputable brands match their ratings. Bottom-tier brands lie.

Installation Mistakes

Most common installation mistake is undersized cabling. Online calculators exist. Use them. Input the current, distance, and acceptable voltage drop. The calculator tells you the minimum wire gauge. Then use one size bigger because real-world conditions are never ideal.

Second most common mistake is poor terminal connections. Crimp properly using a real crimping tool, not pliers. Apply dielectric grease. Use heat shrink. Torque to spec. Check again in six months because vibration loosens things.

Third mistake is inadequate ventilation. LiFePO4 doesn't vent much during normal operation, it does generate heat during heavy discharge. A pack stuffed in a sealed compartment without airflow will run hotter than necessary, which accelerates aging. A small fan or even passive convection through strategically placed vents helps.

Fusing is not optional. Every positive cable leaving the battery needs a fuse rated for the cable, located within 7 inches of the battery terminal. When something shorts downstream, the fuse blows before the cable catches fire. Class T fuses for high-current DC applications. ANL fuses are second choice. Automotive blade fuses can't handle the current and voltage.

Never Mix Battery Types

Mixing battery types causes problems that aren't immediately obvious. Connecting lithium and lead-acid in parallel seems like it would work, and sometimes it does for a while. Lithium has a much flatter discharge curve than lead-acid. When the lithium reaches its low voltage cutoff, the lead-acid might still be at 50% capacity. Now you have lead-acid trying to push current into disconnected lithium through the charging circuit. Or you have lead-acid carrying the entire load and sulfating from the abuse. Keep battery chemistries separate.

Ground fault protection matters for larger installations. A single ground fault in an ungrounded system might go unnoticed for months, creating a shock hazard and potential for a second fault to create a short circuit. Ground fault circuit interrupters designed for DC systems exist but aren't common in small installations. At minimum, check resistance between the positive bus and ground, and between the negative bus and ground, during annual inspections. Any reading under a few hundred kilohms indicates a developing fault.

Cable routing through bulkheads requires proper glands or grommets. Cables rubbing against sharp metal edges will eventually chafe through insulation. The resulting short might happen at 3am and nobody will be awake to smell the smoke. Rubber grommets, plastic bushings, or proper cable glands prevent chafe failures.

Lifecycle Economics

Sticker price of lithium versus lead-acid is misleading. What matters is cost per kWh delivered over the battery's life.

Cost Per kWh: Lead-Acid vs LiFePO4

$5.00

Lead-Acid per kWh Lifetime

$1.67

LiFePO4 per kWh Lifetime

A 200Ah 12V lead-acid battery costs maybe $200 and delivers around 400 cycles to 50% depth of discharge. That's 40kWh of lifetime throughput at $5 per kWh.

A 200Ah 12V LiFePO4 battery costs maybe $800 and delivers around 3000 cycles to 80% depth of discharge. That's 480kWh of lifetime throughput at $1.67 per kWh.

Lithium costs three times more but delivers twelve times the energy. On a per-kWh basis, lithium is one-third the cost of lead-acid. Even if the lithium only lasts half as long as promised, it's still cheaper.

That calculation ignores efficiency differences, which favor lithium further. Lead-acid wastes 15-20% of charging energy as heat. LiFePO4 wastes 5-8%. Over thousands of cycles, that efficiency gap adds up.

Maintenance differences favor lithium too. Lead-acid needs periodic equalization charges, water addition for flooded types, and terminal cleaning. LiFePO4 needs nothing except annual inspection of connections.

Resale value is another factor. Lead-acid batteries are essentially worthless used. Nobody wants to buy a battery that might have 30% capacity remaining or might be sulfated beyond recovery. LiFePO4 batteries retain significant resale value because buyers can verify remaining capacity through BMS data. A five-year-old lithium pack with 85% capacity remaining might sell for 50-60% of new price.

Insurance considerations have shifted in lithium's favor. Early concerns about lithium battery fires focused on chemistries other than LiFePO4. As the safety record of iron phosphate has accumulated, insurers have become more comfortable. Some marine insurers now specifically exclude certain lithium chemistries while accepting LiFePO4 without surcharge. Check with your insurer before installing any lithium system.

Time value of money slightly favors lead-acid for the math nerds. Spending $200 now versus $800 now means that $600 could be invested elsewhere. At modest investment returns, the deferred cost of multiple lead-acid replacements could theoretically be cheaper than one upfront lithium purchase. In practice, nobody actually invests their lead-acid savings, and the convenience of not swapping batteries every few years has real value.