Technology & Science

What Are Lithium Batteries and Their Role in Modern Technology

Marcus Chen

December 15, 2024

Global demand for rechargeable power storage shattered the one-terawatt-hour threshold in late 2024, with lithium-ion technology commanding over 80% of this massive market. This dominance was no accident of history but the result of three decades of steady engineering progress since Sony shipped the first commercial cells in 1991. During that span, volumetric energy density tripled while costs plummeted by 90%. Many skeptics predicted diminishing returns from electrochemistry, but they turned out to be wrong. These rechargeable power sources now animate everything from smartphones to electric vehicles, from grid-scale storage installations to surgical robots.

The lithium battery underpins much of modern life in ways most people never notice. Remove it, and things fall apart quickly: phones die mid-conversation, laptops freeze, electric vehicles strand their occupants somewhere inconvenient. Even pacemakers would stop. Understanding the technology is essential knowledge, though most consumers get by perfectly fine without knowing what an intercalation electrode is. They just want their phone to last through dinner.

Electric vehicles have become one of the most visible applications of lithium-ion battery technology, fundamentally changing transportation infrastructure worldwide.

Understanding Lithium Battery Technology

The term "lithium battery" encompasses a family of energy storage devices that exploit lithium ions as the primary mechanism for storing electrical charge. At the most fundamental level, the distinction hinges on whether the device contains metallic lithium (primary, non-rechargeable) or employs lithium compounds in an intercalation process (rechargeable lithium-ion). The rechargeable variants have achieved overwhelming commercial dominance, powering portable electronics and electrified transportation across every continent.

The foundational breakthrough emerged through work spanning the 1970s and 1980s, a period when oil crises concentrated scientific attention on alternative energy storage. M. Stanley Whittingham conceived intercalation electrodes in the 1970s while working at Exxon, demonstrating that lithium ions could insert reversibly into layered titanium disulfide. John Goodenough expanded this work dramatically in 1980 at Oxford, identifying lithium cobalt oxide as a cathode material that doubled the voltage Whittingham achieved. Akira Yoshino at Asahi Kasei completed the puzzle in 1985, pairing Goodenough's cathode with a carbonaceous anode to create the first prototype resembling modern lithium-ion cells. Sony commercialized the technology in 1991, initially for camcorders. These three scientists received the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their contributions. It took the Nobel committee nearly three decades to recognize them, which indicates how slowly academic recognition moves compared to commercial adoption.

I remember reading about Goodenough a few years back—the man was still publishing papers well into his nineties. There is something almost absurd about the fact that the person who made your smartphone possible was born before the Great Depression. He passed away in 2023 at 100 years old. The obituaries mostly focused on the Nobel Prize, but what struck me was how long he kept working. Most people retire at 65. He was refining solid-state electrolyte concepts at 95. I am not sure what that says about scientific passion or stubbornness or both.

Anyway.

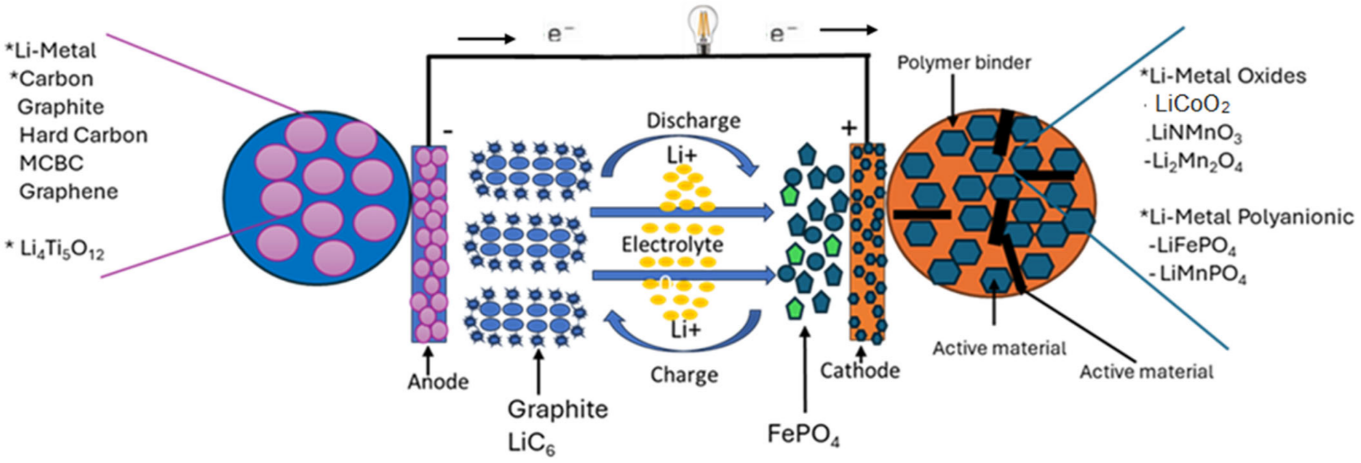

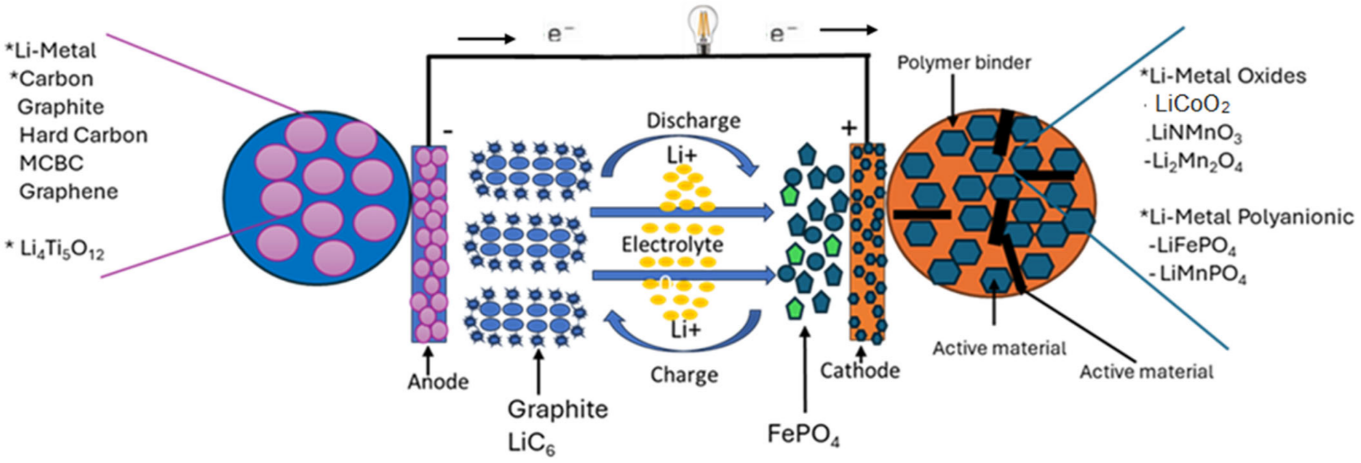

What constitutes a lithium battery varies by specific chemistry, but all variants share common operating principles. They store energy by establishing an electrical potential difference between negative and positive poles. An insulating separator divides these poles while permitting lithium ions to traverse. During discharge, ions migrate from anode to cathode, compelling electrons to flow through external circuits to power devices. Charging reverses this ionic migration. Unlike primary batteries that consume their reactants irreversibly, lithium-ion cells can cycle thousands of times with minimal degradation when properly managed.

The physics underlying lithium-ion operation reward careful examination. Lithium occupies a unique position in the periodic table: the lightest metal, the third-lightest element overall, with an atomic mass of merely 6.94 grams per mole. This featherweight character translates directly into high gravimetric energy density, meaning more energy stored per kilogram than any competing rechargeable chemistry. Lithium also possesses the most negative standard electrode potential of any element (around -3.04V versus standard hydrogen electrode), enabling high cell voltages that minimize the number of cells required for a given system voltage. No other element offers this combination of properties. Sodium comes close and is cheaper, which is why sodium-ion batteries continue to be promoted as "the next big thing," but they have not displaced lithium yet.

Modern lithium-ion cells are engineered to atomic-scale tolerances, with each component playing a critical role in the battery's performance and safety.

Core Components and How They Work

Every rechargeable lithium cell contains five essential components operating in precise coordination, each engineered to atomic-scale tolerances. The anode (negative electrode) stores lithium ions when charged, typically constructed from graphite. Specifically, highly ordered pyrolytic graphite whose layered crystal structure accommodates lithium ions between graphene sheets. Silicon increasingly appears as an additive or replacement, offering roughly ten times the theoretical capacity of graphite but suffering from dramatic volume expansion during lithiation that pulverizes electrode structures. This expansion reaches up to 300%, which is enormous at the microscale. Modern anodes blend small percentages of silicon with graphite, capturing partial capacity gains while managing mechanical stress through sophisticated binder systems and nanostructured silicon particles.

The cathode (positive electrode) serves as the lithium reservoir and determines the cell's voltage window and capacity ceiling. Common cathode materials include lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2), lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4), and lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC). Each involves distinct tradeoffs. Lithium cobalt oxide delivers the highest volumetric energy density, and that is why it persists in space-constrained smartphones. But it contains expensive, ethically problematic cobalt and exhibits thermal instability above 150°C. Lithium iron phosphate sacrifices about 30% of the energy density but withstands temperatures exceeding 270°C without decomposition and costs far less. NMC chemistries occupy middle ground, with tunable ratios allowing manufacturers to dial in specific performance characteristics. There is no perfect cathode material, just different compromises.

The electrolyte carries lithium ions between electrodes while blocking electrons. Ions yes, electrons no. But doing this reliably across thousands of cycles, at varying temperatures, without degrading or catching fire, turns out to be difficult. Traditional designs dissolve lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) in organic carbonates, typically mixtures of ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate. These organic solvents are the reason lithium batteries can burn. They ignite readily at elevated temperatures, and when they do, they release toxic fluorine compounds. Solid-state alternatives have been "five years away" for about fifteen years now. Manufacturing challenges and interfacial resistance problems keep defying solution, though every battery conference features someone claiming they have finally cracked it.

The separator and current collectors complete the cell architecture. I will spare you the detailed breakdown—suffice to say the separator keeps electrodes from touching (catastrophic if they do), and current collectors are just copper and aluminum foils that move electrons around. The engineering is precise, the tolerances are tight, and none of it is particularly exciting to describe.

During discharge, lithium atoms in the anode lose electrons and become ions. These ions then make their way through the electrolyte—migrating through a viscous organic solvent. They migrate to the cathode, recombine with electrons that took the long way around through the device's circuitry, and settle into the cathode's crystal structure. The separator blocks the electrons from taking a shortcut through the battery itself, which is the reason the device gets power instead of the battery just heating up uselessly.

A fully charged lithium cobalt oxide cell maintains approximately 4.2 volts; as discharge proceeds and lithium depletes from the anode, voltage gradually declines to a cutoff around 3.0 volts.

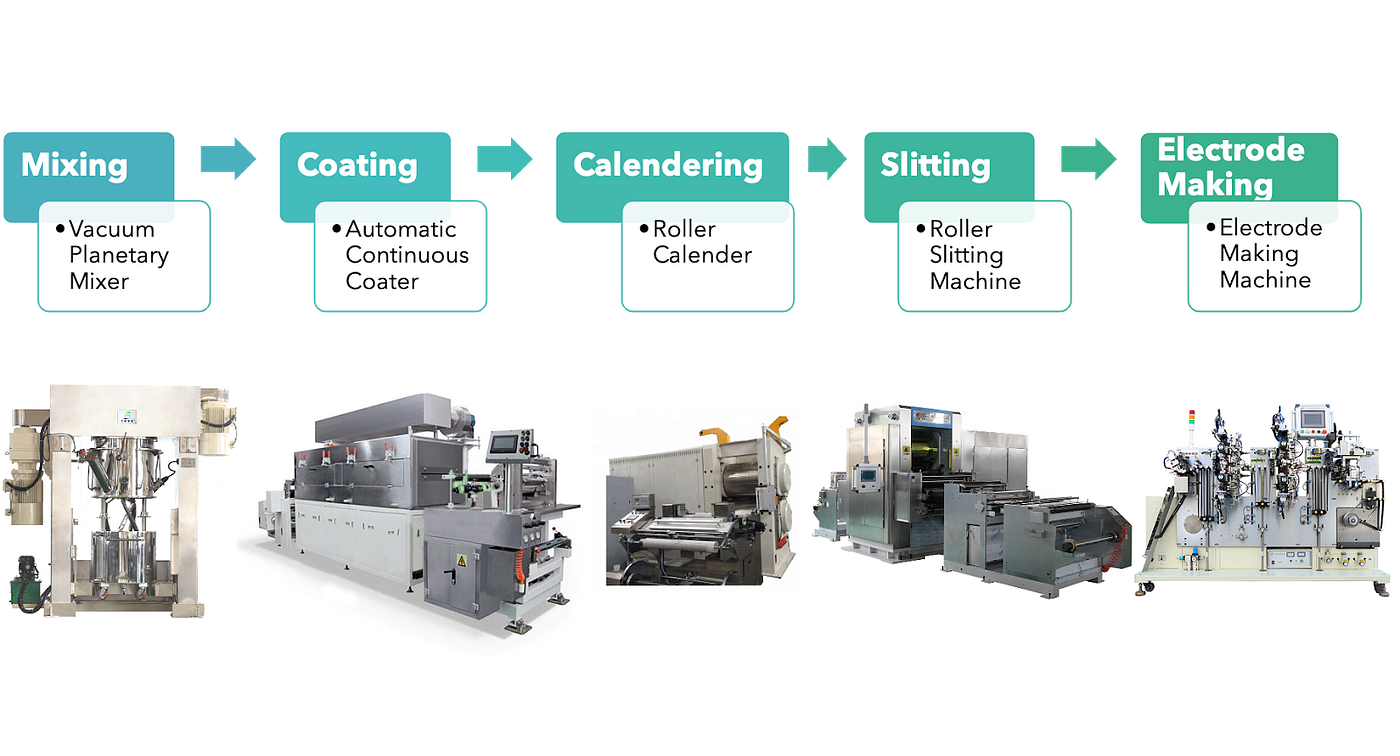

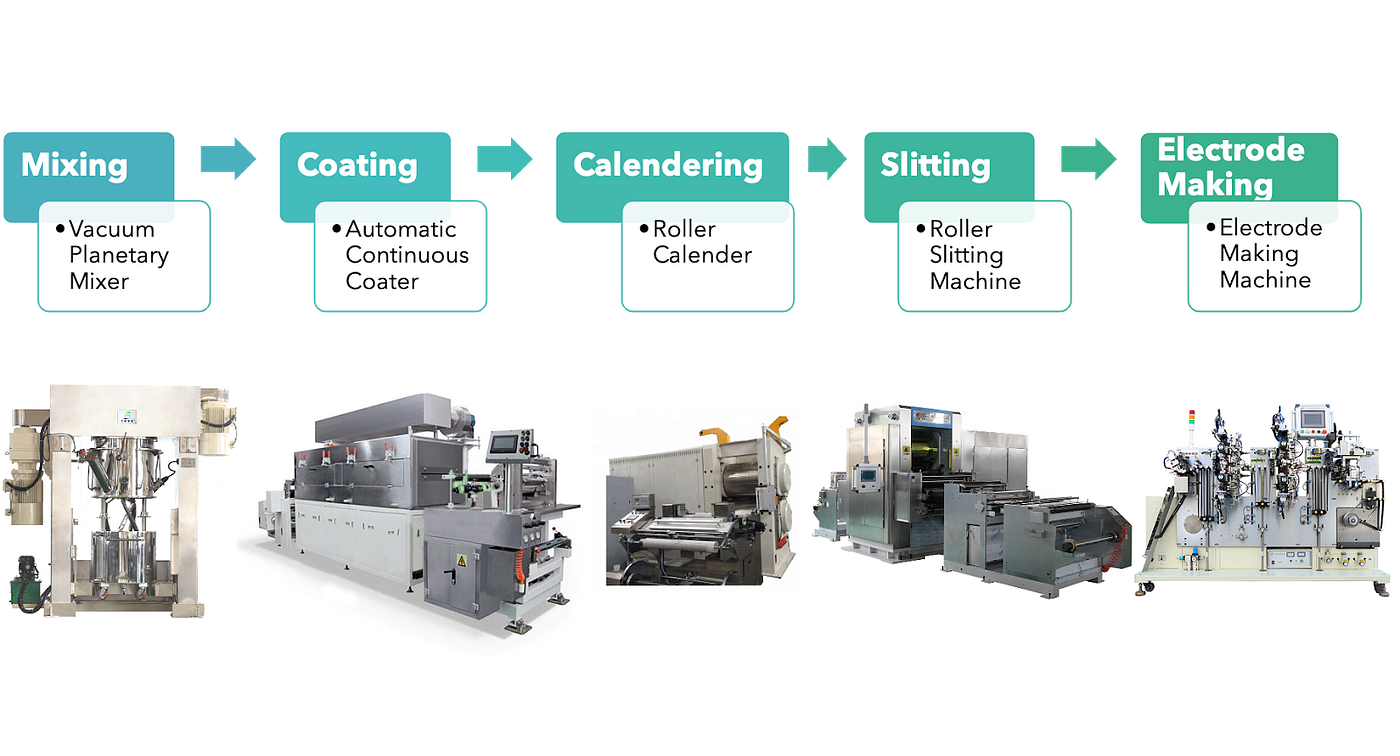

Battery manufacturing requires precision engineering and stringent quality control at every stage of production.

Charging reverses the process through applied electrical pressure. When connected to a power source exceeding cell voltage, lithium ions release from the cathode lattice and travel back to the anode. The ions insert between graphene layers in graphite anodes through intercalation, a process where the layered structure accommodates ions with minimal lattice distortion. Stage formation occurs: lithium ions first occupy distant interlayer galleries, then progressively fill nearer spaces as charging continues. This actually changes the graphite's color from black through blue to golden at full lithiation. This reversibility enables thousands of charge-discharge cycles, though side reactions gradually consume lithium inventory and degrade electrode structures.

The Battery Management System (BMS) monitors everything—voltage, temperature, current—and intervenes the moment anything appears abnormal. The practical result is that the battery does not explode when left charging overnight, which is more of an achievement than most people realize. The BMS prevents overcharging, protects against over-discharge, and manages thermal conditions. In multi-cell packs, it also has to balance charge across cells, which is a difficult task because cells age differently even when they are manufactured identically. The reasons why sister cells from the same production batch diverge over time remain not fully understood.

State-of-charge estimation presents challenges. How does one determine how much energy remains in a battery? One cannot simply use a dipstick like a gas tank. The BMS uses a combination of coulomb counting (tracking electrons in and out), voltage measurements, and increasingly sophisticated algorithms. Manufacturers claim impressive accuracy numbers, though batteries frequently die at "15% remaining" in practice.

Cell voltage varies by chemistry, reflecting differences in cathode crystal structure and lithium binding energy. Standard lithium-ion cells operate at nominal 3.6-3.7V, ranging from approximately 3.0V when depleted to 4.2V when fully charged. Lithium iron phosphate cells operate at lower 3.2V nominal voltage due to the iron redox couple's electrochemical potential but exhibit remarkably flat discharge curves, a characteristic simplifying state-of-charge estimation. When manufacturers advertise a "12V lithium battery," it contains four LiFePO4 cells connected in series (4 × 3.2V = 12.8V), offering near drop-in replacement for traditional 12V lead-acid batteries while delivering triple the cycle life at half the weight.

Types of Lithium Batteries

I am not going to catalog every lithium battery chemistry in existence. There are too many, and half of them only matter to specialists. But a few deserve attention.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO₄ or LFP)

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4 or LFP) has earned its reputation primarily through longevity. These cells routinely deliver impressive cycle counts at deep discharge levels—installations have remained operational after eight years of daily cycling. The olivine crystal structure stays mechanically stable through repeated lithiation, and the strong phosphate bonds require temperatures above 270°C to release oxygen. That is well above the threshold where most other cathodes become dangerous. RV owners, marine applications, and electric bus fleets have gravitated toward LFP for these reasons. The chemistry does sacrifice energy density compared to NMC, and cold weather performance suffers noticeably below -10°C as lithium diffusion slows in the phosphate lattice. For applications where space and weight matter less than lifespan and safety, LFP usually wins. Though some EV engineers consider LFP overhyped for passenger vehicles.

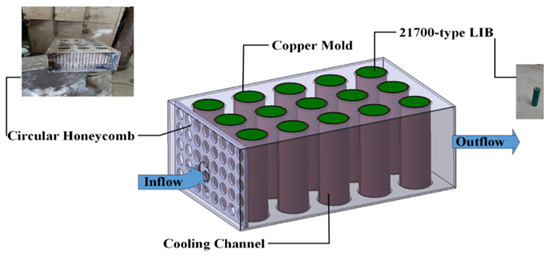

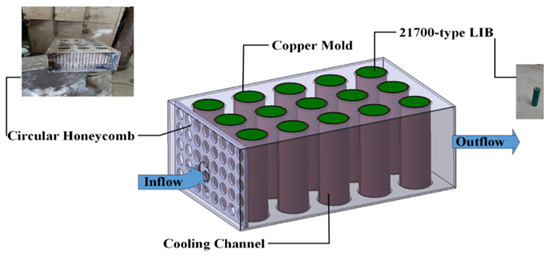

Modern EV battery packs integrate thousands of individual cells with sophisticated thermal management and safety systems.

Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO)

Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) batteries pack the most energy into the smallest space. That is why they have persisted in smartphones, tablets, and laptops despite years of predictions about their demise. The layered rock-salt structure accommodates high lithium loading. But LCO demands careful handling. Push it too hard and the structure destabilizes, releasing oxygen that can combust with the electrolyte. Cobalt prices fluctuate wildly, supply chains concentrate in politically unstable regions, and documented child labor in artisanal mining has pushed manufacturers toward alternatives. The cobalt situation presents a complex intersection of smartphone demand, Congolese mining operations, and child welfare.

Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC)

Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC) dominates electric vehicles because it does not force engineers to choose between range, cost, and safety. It delivers acceptable performance across all three, which matters more than excellence in any single dimension. Tesla, BMW, Volkswagen, and most major EV manufacturers rely on NMC variants. The chemistry blends nickel (high capacity), manganese (structural stability), and cobalt (favorable kinetics). Different atomic ratios tune the balance: NMC 111 prioritizes stability with equal parts of each metal; NMC 811 pushes to 80% nickel for higher energy density but requires surface coatings, gradient compositions, and single-crystal morphologies to manage the instabilities. The industry's push toward higher nickel reflects pressure for longer driving range, though each step up the nickel ladder multiplies engineering challenges.

There are other chemistries—LMO for power tools, NCA for some Tesla models, LTO for fast-charging applications—but honestly, if you are not designing battery packs for a living, the distinctions blur together. What matters is that different applications demand different tradeoffs, and no single chemistry wins everywhere.

Industry Breakthrough

Real-world deployment shows how chemistry selection has matured. In April 2025, CATL unveiled its Shenxing Plus battery, the first lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery claiming 1,000 km range on a single charge with 4C ultra-fast charging. The company claims 600 km range added in 10 minutes, though independent testing will be needed to verify these numbers. This breakthrough demonstrates how continuous innovation pushes perceived chemistry limitations. LFP's energy density disadvantage, once considered insurmountable, yielded to cell-to-pack integration eliminating module-level inefficiencies. The announcement threatens to disrupt the NMC-dominated premium EV market by offering comparable range without cobalt's cost and ethical baggage.

Performance Characteristics

Energy density separates lithium technology from alternatives with decisive finality. Modern lithium-ion cells vastly outperform lead-acid batteries. The practical advantage translates directly into lighter weight and smaller volume for equivalent capacity. Aircraft employ lithium batteries exclusively for starting engines and powering avionics; the weight savings translate into fuel efficiency and payload capacity. Portable medical equipment, professional camera systems, and expedition gear all exploit this advantage to enable capabilities impossible with heavier chemistries.

Power density indicates how quickly a battery can deliver its stored energy. Energy density represents reservoir capacity and power density represents pipe diameter. Lithium-ion excels at both simultaneously, a combination older chemistries could not achieve. This is why electric vehicles can achieve acceleration that embarrasses internal combustion counterparts: the instantaneous torque from electric motors requires batteries capable of delivering massive power without voltage collapse.

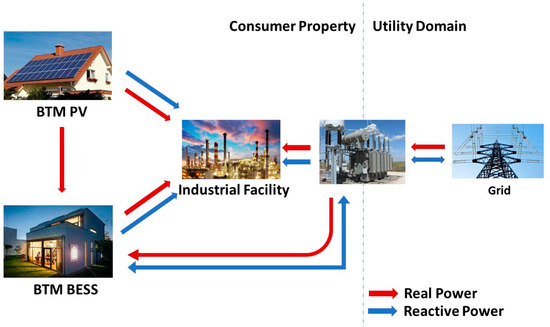

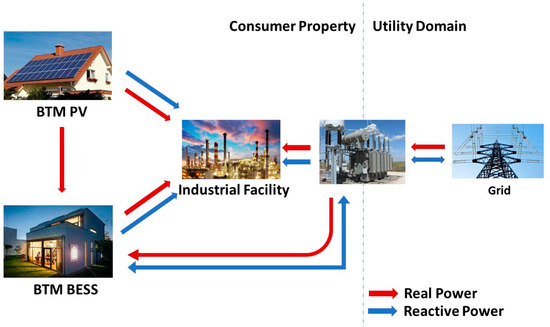

Grid-scale battery storage installations are increasingly paired with renewable energy sources, creating more resilient and sustainable power systems.

Cycle life is where lithium excels, especially LiFePO4 variants. Quality cells last a long time under proper operating conditions. Compare this to lead-acid batteries that need replacement far more frequently. Over a decade in daily cycling applications, the math works out strongly in lithium's favor even with higher upfront costs. Solar installers increasingly specify lithium for this reason. Though it should be noted that these cycle life numbers assume ideal conditions. Real-world results vary based on temperature, charge rates, and depth of discharge. Batteries frequently fail well short of their rated cycle life because of abuse or poor thermal management.

Self-discharge rate measures how quickly batteries lose charge during storage. Lithium-ion batteries self-discharge slowly compared to alternatives. This low self-discharge enables seasonal equipment like boats, RVs, motorcycles, and lawn tractors to sit for months and start reliably. A lithium battery at partial charge can store for a long time without intervention, while lead-acid batteries demand maintenance charging regularly to prevent sulfation that permanently reduces capacity. This characteristic alone justifies lithium conversion for equipment used intermittently.

The absence of memory effect eliminates a frustration that plagued older nickel-cadmium batteries, where partial discharge cycles gradually reduced usable capacity. Lithium batteries accept partial charging and discharging without capacity penalty. Topping off a lithium battery pack at any charge level carries no consequence; users charge opportunistically whenever convenient rather than adhering to full discharge cycles. This flexibility suits modern usage patterns.

Temperature tolerance varies by chemistry but generally spans a reasonable operating range, with optimal performance in moderate temperatures. LiFePO4 cells handle temperature extremes better than LCO variants due to stronger phosphate bonds that resist decomposition. Storage should occur at moderate temperatures. Some modern designs incorporate heating elements that automatically warm cells in cold weather, enabling charging below freezing when unheated cells cannot accept charge due to lithium plating risk. Tesla vehicles route coolant through battery packs, maintaining cells within optimal temperature windows regardless of ambient conditions.

Practical Guidelines for Use and Maintenance

Charging optimization extends battery lifespan substantially. Research has identified practices that maximize longevity, with charge level management proving most impactful. Minimizing time spent at full charge or empty reduces stress that accelerates aging. At full charge, elevated voltage drives parasitic reactions; at empty states, adverse effects occur at the anode. Modern research recommends maintaining charge between 20-80% for daily use when maximum longevity matters more than maximum range. Samsung, Apple, and other manufacturers now include software features that halt charging at 80% overnight. Whether most users actually enable these features is another question.

Charging speed affects longevity through thermal and electrochemical mechanisms. Fast charging degrades cells more quickly than standard charging. Slower charging produces less heat and reduces stress within electrode particles. Reserve fast charging for situations requiring rapid turnaround; overnight charging should employ slower rates that complete gently over hours rather than minutes.

Modern smartphones incorporate sophisticated charging algorithms designed to extend battery lifespan while balancing user convenience.