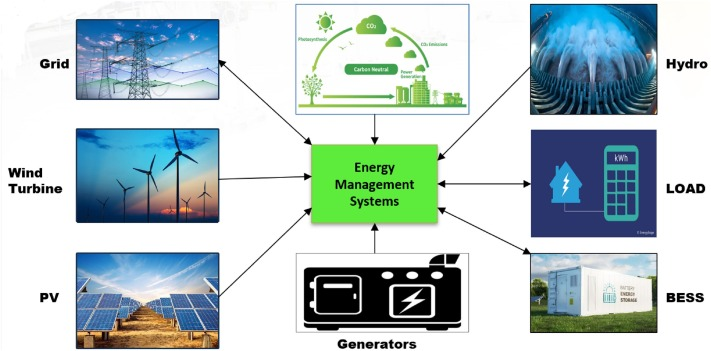

What is Energy Management System

The three letters EMS are severely overused.

Open any energy software company's website, and you'll see "Smart Energy Management System." Then look at the feature list: data collection, visualization dashboards, report exports, alarm notifications. And then? Nothing more.

This is not an energy management system. This is a database frontend with charts.

A real EMS must answer: what to do next. Should the air conditioning temperature go up or down? Should the energy storage charge or discharge now? Are two of three chillers enough? These decisions can't rely on human gut feelings, because there are too many influencing factors. Electricity prices are changing, loads are changing, weather is changing, equipment status is changing. The human brain can't compute all of this.

A system that can compute all of this deserves to be called an EMS.

Modern energy management requires sophisticated control systems that can process multiple variables simultaneously

The ISO definition is useless

ISO 50001 says an energy management system is "a set of interrelated elements to establish energy policies, objectives, and processes to achieve those objectives."

What engineers need as a definition: EMS is a feedback control system. Measure current state, predict future state, calculate optimal actions, execute, verify results, adjust. Repeat continuously.

Missing any of these elements means it's incomplete.

Why? Execution means responsibility. If the air conditioning is adjusted wrong and people overheat, if energy storage operates in reverse and batteries explode, if chiller switching is improper and pipes freeze, who's responsible? Software companies don't dare take on that liability, and clients don't dare hand over control. So everyone tacitly agrees to keep systems at the "recommendation" level, only producing reports, never taking action.

The technology is all readily available. It's stuck on trust.

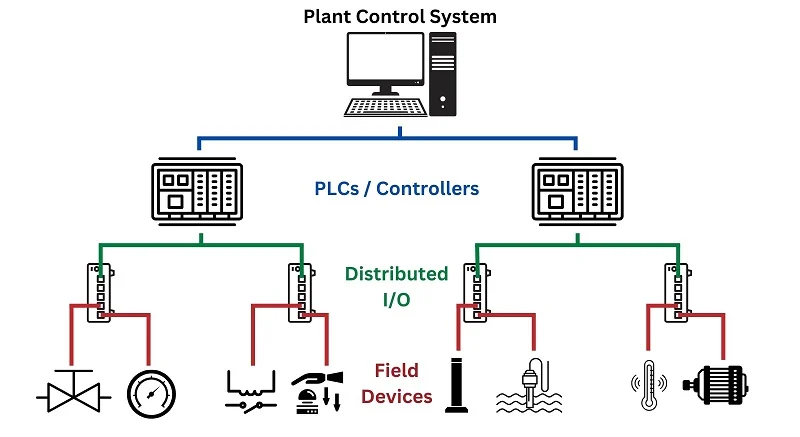

SCADA, BMS, DCS

People working in energy management deal with these systems every day, but many can't clearly explain the boundaries.

SCADA

SCADA is responsible for "seeing" and "acting." It collects data fast, at millisecond level, with wide coverage across hundreds of thousands of measurement points, and can remotely operate equipment. But SCADA doesn't think. If you ask it "how to allocate generation tasks most economically," it can't answer. That question needs the economic dispatch module of the EMS to calculate.

BMS

BMS only manages batteries. Cell voltage balancing, SOC estimation, thermal runaway warning, charge-discharge protection. Its decision boundary is inside the battery pack: it doesn't care whether the pack is doing peak shaving or participating in frequency regulation, doesn't care about electricity prices.

DCS

DCS manages production processes. Reaction temperatures in chemical plants, fractionation pressures in refineries, boiler combustion in power plants. It pursues stable process parameters and consistent product quality. Energy is just one consideration, usually not the most important one.

Dispatch center systems are usually called SCADA/EMS. SCADA serves as the eyes and hands, EMS serves as the brain. In industrial and building sectors, they may not be integrated; they might be two independent systems communicating through interfaces.

EMS stands at a higher level: charge or discharge now? At what power level? Until when? These decisions must integrate electricity prices, load forecasting, PV output, and grid dispatch commands. BMS executes EMS commands while ensuring battery safety.

When BMS protection actions conflict with EMS dispatch commands, BMS takes priority. No exceptions.

A good EMS continuously reads the available power range reported by BMS and optimizes within that range, avoiding issuing a bunch of ineffective commands that can't be executed.

When process requirements conflict with energy optimization, DCS chooses process.

The deep end of industrial energy conservation lies in the coordination between EMS and DCS. Surface-level energy-saving measures are easy to do but have limited potential, such as switching to LED lights, adding variable frequency drives, doing waste heat recovery. The real opportunity is in process optimization, which requires energy engineers and process engineers to sit together and figure out which parameters can be adjusted and by how much without affecting product quality. Pure data-driven black-box models are basically useless here.

Industrial control systems require seamless integration between SCADA, BMS, DCS and EMS layers

The four-layer architecture is easy to draw but hard to implement

Device layer, communication layer, platform layer, application layer: a PPT can be drawn in three minutes. Every layer has pitfalls when implementing.

Device Layer

The problem is chaos. An ordinary industrial park might have a dozen different electricity meter brands, seven or eight PLC models, and BMS systems of varying ages.

Communication Layer

The trouble is the harsh industrial field environment. Basement electrical rooms, remote pump stations, high-temperature boiler rooms, welding shops with severe electromagnetic interference.

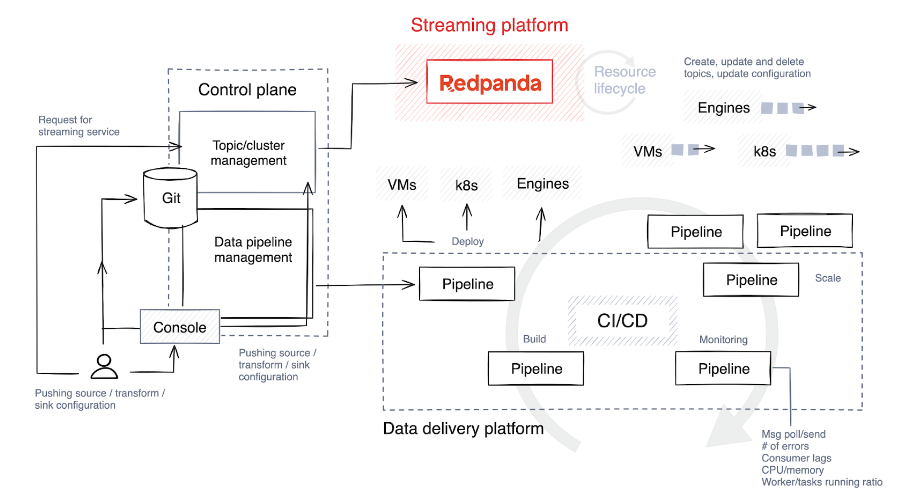

Platform Layer

Classic big data problems. A medium-sized park with several thousand measurement points generates tens of thousands of records per minute, billions of data points per year.

Application Layer

The problem is user differentiation. Energy managers need professional analysis tools, operations staff need simple interfaces, bosses need clear KPI dashboards.

They speak different protocols: Modbus RTU, Modbus TCP, BACnet/IP, PROFINET, proprietary protocols. They run on different network environments: RS485 buses, industrial Ethernet, wireless mesh. Data formats vary wildly: big-endian, little-endian, BCD code, IEEE floating point.

Protocol gateways solve the heterogeneity problem. But "plug and play" is a myth in energy systems. On-site commissioning frequently encounters: register addresses not matching device manuals, data type parsing errors, communication timeout parameter mismatches, multi-master polling conflicts. There's no shortcut; you have to debug device by device.

Software development might take two weeks; device commissioning takes two months.

Planning measurement points: more is not better, measurement has costs. The main incoming line must have it, sub-areas or workshops preferably have it, key equipment should have it, the rest can be derived by subtracting measured portions from totals. Rough principle: measurement investment shouldn't exceed one-fifth of expected annual energy savings.

The trouble with the communication layer is the harsh industrial field environment. Basement electrical rooms have two bars of 4G signal, remote pump stations have no network coverage, boiler rooms at 50-60°C are too hot for WiFi equipment, welding shops have severe electromagnetic interference causing frequent RS485 packet loss.

There's no universal solution. Use wired if possible, otherwise use 4G/5G, if that doesn't work try LoRa, and if nothing else works use power line communication. Design proper mechanisms for disconnect detection, automatic reconnection, and data backfill.

The platform layer has the classic big data problems. A medium-sized park with several thousand measurement points generates tens of thousands of records per minute, billions of data points per year. MySQL can't handle it, so use a time-series database. InfluxDB has a mature ecosystem but the cluster version costs money, TimescaleDB is PostgreSQL-compatible but operationally complex, TDengine is domestic Chinese but has a small community. Selection should rely on actual stress testing, not official website performance claims.

What's more troublesome is algorithm deployment. Optimization algorithms in papers all assume clean data, accurate models, and ample computation time. In reality, missing data, erroneous data, and model drift are the norm, and many scenarios require second-level decisions with no time to run half-hour optimizations. Algorithm robustness matters more than sophistication. An algorithm that can give a passable answer under all kinds of abnormal conditions is more useful than one that only excels under ideal conditions.

The problem with the application layer is user differentiation. Energy managers need professional analysis tools, operations staff need simple operation interfaces, bosses need clear KPI dashboards. The same system serving different roles requires layered interfaces and tiered permissions.

There's also the configurability of business rules. Different enterprises have different electricity price structures, different metering allocation rules, different assessment metrics. If these rules are hard-coded, every change requires code modification, and maintenance costs will explode. Good products make business rules configurable.

platform architecture must handle billions of data points while maintaining real-time responsiveness

Data Collection

What to collect, where to collect, how often to collect, how to ensure data quality.

Collection scope is an economic question. Theoretically every piece of equipment should be individually metered, but that's too expensive. Equipment consuming more than 5% of energy must be individually metered, 1% to 5% can be sampled or combined, below 1% can be derived by subtracting metered portions from totals.

Collection Frequency Guidelines

- Monthly reports just need one daily cumulative value

- Demand management needs to capture the maximum average power in 15-minute sliding windows, requiring at least once per minute

- Real-time monitoring needs to see instantaneous load fluctuations, within 10 seconds

- Power quality analysis needs to catch voltage sags and harmonic distortion, potentially requiring millisecond level

Higher frequency means larger data volume and higher storage costs, so don't apply one standard across the board.

Data quality governance is dirty, tedious work. Data collected from the field is riddled with problems: gaps due to communication interruptions, anomalous values from sensor failures, timestamp errors from unsynchronized clocks, unit confusion from configuration errors. You need reasonableness checks, trend analysis, correlation checks, interpolation algorithms. If data quality problems aren't solved at the source, everything downstream is garbage in, garbage out.

Load Forecasting

Whether forecasts are accurate directly determines the effectiveness of optimized dispatch.

Accurate forecasting systems can arrange equipment start-stop combinations in advance, design energy storage charge-discharge plans, and formulate demand response participation strategies. Inaccurate forecasting systems can only passively respond to load changes that have already occurred, compressing optimization potential.

Factors affecting energy consumption fall into three categories. Exogenous: temperature, humidity, solar radiation, wind speed, workday or weekend, electricity price signals. Endogenous: production schedules, equipment status, personnel activity. Inertial: daily cycles, weekly cycles, and seasonal cycles in historical load curves.

Algorithm selection should match data conditions. With little data but clear patterns, traditional statistical methods are more robust than deep learning, including regression, ARIMA, and exponential smoothing. With lots of data, high volatility, and complex cycles, LSTM and Transformer have advantages. But don't worship algorithm sophistication. The quality and richness of input features often has more impact on forecast accuracy than improvements in the algorithm itself.

Whether weather forecasts are accurate, whether production schedules can be obtained in advance, whether sudden events can be sensed in time: these "soft factors" have far more impact than tuning parameters in papers.

Optimized Dispatch

The objective function is easy to write: cost minimization. Electricity cost plus gas cost plus carbon cost minus demand response subsidies.

The hard part is constraints. Equipment power upper and lower limits, ramp rate limits, minimum start-stop times, energy storage SOC ranges, supply-demand balance, voltage and frequency ranges, reserve capacity requirements, temperature comfort zones, maximum demand limits, demand response obligations. Constraints determine the boundary of feasible solutions; the objective function just picks the optimal one within the feasible region.

Algorithm selection depends on problem characteristics. Use linear programming or nonlinear programming for continuous decision variables. Use mixed-integer programming for discrete decisions like start-stop, but computational complexity increases sharply. Use robust optimization or stochastic programming for uncertainty. For large-scale problems or real-time decisions, consider reinforcement learning and approximate dynamic programming.

Deep reinforcement learning deployment still faces several hurdles. Training requires extensive trial and error, and training directly on real systems is too risky. Learned policies are black boxes that can't be explained, making accountability difficult when problems occur. Policy transferability is questionable: can a policy trained on System A be used on System B? Currently, the viable approach is to first train in a digital twin environment, then transfer to real systems for minor fine-tuning.

Grid EMS vs. Enterprise EMS

The primary objective of grid EMS is safety; economics comes second.

AGC, or Automatic Generation Control, is the core. Power systems must maintain generation-consumption balance at all times; slight deviations cause frequency fluctuations, large deviations trigger protection or even cascading failures. AGC controls frequency deviation within allowable ranges by adjusting generator output.

Frequency Regulation Levels

- Primary frequency regulation relies on generator governors responding automatically, at second level

- Secondary frequency regulation relies on AGC calculating adjustment amounts based on area control error and issuing commands, at minute level

- Tertiary frequency regulation is economic dispatch, optimizing output allocation over longer time scales

High penetration of renewable energy is reshaping AGC. Previously only loads fluctuated, and generation was basically controllable. Now with large-scale wind and solar integration, the generation side has also started fluctuating significantly. "Source-load dual fluctuation" places higher demands on both AGC's regulation speed and capacity. Regulation periods are moving from 4 seconds toward 2 seconds and 1 second, the pool of adjustable resources is expanding to include energy storage and controllable loads, and predictive control is being introduced.

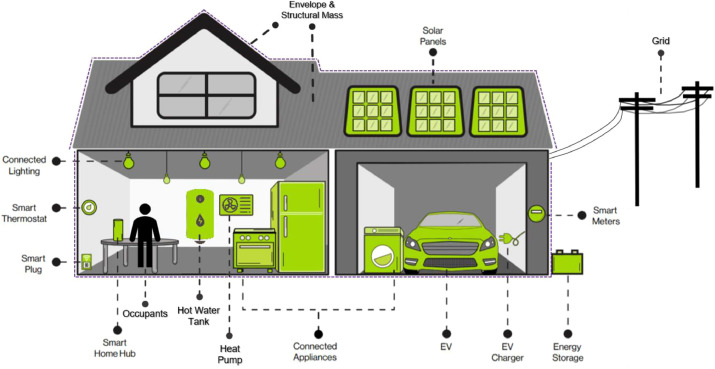

The primary objective of enterprise EMS is cost reduction or carbon reduction, depending on what the boss cares about.

Industrial EMS must integrate with MES to deliver value. Energy consumption analysis disconnected from production context is superficial. The same energy consumption figure is normal at full production but wasteful at half production. The same equipment power is reasonable when producing Product A but might be abnormal when producing Product B. Linking energy consumption with output, equipment with processes, anomalies with causes: this is what distinguishes industrial EMS from generic energy monitoring.

Demand management is a high-value feature. Large industrial users operate under two-part tariffs, paying demand charges in addition to energy charges. Demand charges are based on the monthly maximum 15-minute average power, accounting for 20-30% of total electricity costs. Once any 15-minute window exceeds the contracted demand, the excess is penalized at two to three times the rate. EMS monitors the average power within the sliding window in real-time; when it's about to exceed, it triggers demand control, such as cutting non-critical loads, reducing air conditioning output, and increasing energy storage discharge. Avoiding one penalty might pay back the entire year's system investment.

The particularity of building EMS is that comfort is a hard constraint. Air conditioning can't overheat people to death just to save electricity. HVAC accounts for the largest share of building energy consumption and is the optimization focus. Chiller plant group control must decide how many chillers to run, how to allocate loads, what chilled water temperature differential to set, and how to adjust cooling tower and pump speeds. The combination space is enormous, and finding the optimal solution through experience-based operation is very difficult. Predictive control adjusts in advance based on weather forecasts and personnel schedules, smoothing load curves and avoiding frequent start-stops better than traditional feedback control.

Building EMS must balance energy optimization with occupant comfort as a hard constraint

Market

The global EMS market in 2024 is roughly $40-50 billion, projected to exceed $100 billion by 2030. Annual growth is in the low teens percentage-wise.

📈 Driving Factors

Carbon neutrality policies are advancing globally, creating rigid demand for emissions-controlled enterprises; energy prices have structurally risen, improving the ROI of energy conservation; technology maturity has crossed a threshold, as systems that cost several million to build ten years ago can now be done for a few hundred thousand.

🏗️ Competitive Landscape

The competitive landscape is pyramid-shaped. At the top are comprehensive energy giants like Schneider, Siemens, ABB, Honeywell, and GE, with full product lines, global service networks, capable of taking on large complex projects, but expensive, slow to respond, and not locally flexible enough.

The middle layer is specialized software companies with deep expertise in certain verticals but unable to do cross-domain integration; their ultimate fate is often acquisition by giants. The bottom layer is system integrators with engineering implementation capability but no proprietary products, doing equipment installation, commissioning, and maintenance work, with thin margins and easily replaced.

The Chinese market has special characteristics. International giants occupy the high-end market, but in the mid-to-low-end market, government projects, and central/state-owned enterprise projects, local companies are rapidly rising through cost advantages, policy support, and localized service capabilities. In emerging fields like renewable energy grid connection, virtual power plants, and carbon management, local companies may actually be ahead because they better understand China's policies and market.

High project failure rate

Many enterprises spend millions building EMS systems that become unused "zombie systems" after going live. It's not a technology problem; it's a management problem.

Top leadership must truly support it. EMS implementation will disturb existing interest patterns and work habits. Equipment maintenance staff worry about being monitored and assessed, workshop directors worry about energy-saving targets affecting production tasks, finance departments question the return on investment. Without strong top-level push, projects will be exhausted in departmental wrangling. Support must be reflected in resource allocation, performance assessment, and reward-punishment mechanisms.

Benefit expectations must be clear. Direct energy-saving benefits, demand management benefits, operational efficiency benefits, compliance benefits, carbon asset benefits: the sources and scale of each benefit must be calculated before project launch. Calculations can't be too conservative, or budgets won't get approved; they also can't be too aggressive, or failing to meet expectations after launch will invite questioning.

Implementation path must be gradual. Projects aiming for comprehensive coverage in one step often fail. The reliable approach is to first select a pilot area with clear boundaries, good data foundation, and willing cooperation, quickly validate value, then replicate and expand.

Operational investment must be sustained. Data quality requires continuous governance, algorithm models require continuous iteration, system functions require continuous optimization based on business changes. Annual operating costs should be at least 15% to 20% of construction investment. Without this funding secured, the project shouldn't be started.

The Future of EMS

Virtual power plants will redefine the business boundaries of EMS. When EMS aggregates large amounts of user-side energy storage, charging stations, and controllable loads, it's no longer just a consumption-side management tool; it becomes an entity that can participate in electricity market trading. The business model shifts from "helping users save money" to "helping users make money."

Carbon management and energy management will merge into one. Future EMS won't be "energy management system plus carbon management module" but "integrated energy-carbon management system." The objective function expands from cost minimization to multi-objective trade-offs between cost and carbon emissions.