The price range for industrial lithium battery cabinets is so wide that quoting a single number is almost meaningless. A 100kWh system can cost anywhere from 200,000 yuan to 650,000 yuan depending on cell grade, BMS type, thermal management, certifications, and what's actually included in the quote. The term "100kWh industrial lithium battery cabinet" covers products so different from each other that comparing prices without understanding specifications is like comparing a used Corolla to a new BMW because they're both cars.

This isn't price gouging or market inefficiency. It's genuinely different products serving different needs at different quality levels. The challenge for anyone researching costs is figuring out which product category matches their actual requirements, then finding competitive pricing within that category.

The China Price Situation

Anyone researching this topic runs into a puzzle: Chinese prices seem impossibly low compared to everywhere else.

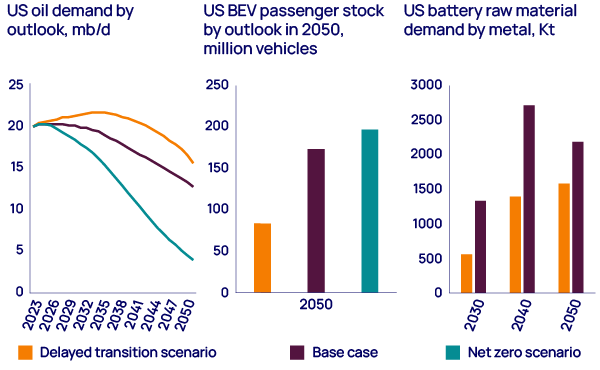

Wood Mackenzie published data showing Chinese storage systems installing at $101 per kWh in 2024, versus $236 in America and $275 in Europe. BloombergNEF reported similar gaps. These aren't cherry-picked numbers or methodology artifacts. The gap is real and it's massive.

Part of the explanation is obvious. Labor costs in Shenzhen run a fraction of labor costs in Texas or Bavaria. But labor is maybe 10-15% of total system cost. It can't explain a gap of 100% or more.

The bigger factor is supply chain concentration. Cathode material producers, anode material producers, electrolyte suppliers, separator manufacturers, cell makers, pack assemblers, BMS developers, cabinet fabricators, system integrators, and all their supporting industries cluster within a few hundred kilometers of each other in Guangdong, Fujian, and the Yangtze Delta region. Component shortage? Call the supplier, truck arrives same day. Quality issue? Drive over and sort it out face to face. Design change needed? The engineering teams can meet in person tomorrow.

Try replicating that density in any other geography. A US manufacturer sources cells from Korea, separators from Japan, BMS chips from Taiwan, and assembles in Tennessee. Lead times measure in weeks or months. Shipping costs add up. Any disruption cascades through the supply chain. The logistics overhead alone adds 10-20% to costs before even considering manufacturing efficiency differences.

Chinese cell manufacturers also built way too much capacity. The China Energy Storage Alliance publishes figures (worth noting they're an industry group with interests in painting a rosy picture, so take with appropriate skepticism) showing domestic cell production capacity exceeding 500 GWh in 2024. Global demand for stationary storage was maybe 200-250 GWh that year. Even adding EV demand doesn't soak up that much overcapacity. Factories running at 50-60% utilization will sell at almost any price to cover fixed costs and keep workers employed.

The result: factory-gate prices in China that would bankrupt manufacturers operating under normal market conditions.

FOB Shenzhen for basic 100kWh cabinet configurations runs 500-600 yuan per kWh at the low end. Delivered and installed at domestic Chinese project sites, 700-900 yuan per kWh is achievable for straightforward installations.

These prices would have seemed fantasy five years ago. They're real today. But they come with caveats that the headline numbers don't capture.

That 500 yuan per kWh cabinet? Almost sure to be B-grade cells. The difference between A-grade and B-grade isn't quality control theater. A-grade cells have capacity, internal resistance, and self-discharge characteristics comfortably within manufacturing specifications. B-grade cells passed quality control but sit at the margins of acceptable ranges. They'll work fine initially. Over thousands of cycles spanning a decade, the weaker cells in a B-grade pack will degrade faster and drag down the whole system.

The cheap cabinet also probably has passive BMS. Passive balancing bleeds off excess charge from high-voltage cells through resistors. It's cheap to implement because it's just resistors and switches. It's also nearly useless for long-term cell health because it only operates during charging, moves tiny currents, and can't actually transfer energy between cells. Cells drift apart over time and passive balancing can't keep up.

Thermal management on cheap systems means air cooling. Maybe just natural convection through vents. That works fine in climate-controlled indoor environments with moderate discharge rates. Put the same system outdoors in Guangdong summers where ambient temperatures hit 35-40°C and solar radiation heats the cabinet further. Internal temperatures climb to 50-60°C or higher. Cell degradation rates roughly double for every 10°C increase above optimal operating temperature. A system rated for 6,000 cycles at 25°C might deliver 3,000 cycles at 40°C average temperature.

Cheap systems also come with warranties from companies that may not exist in five years. The storage industry has seen brutal consolidation. Estimates suggest a hundred or more Chinese companies exited the business or went bankrupt during 2023-2024 alone. A ten-year warranty from a company that disappears in year three is worth exactly nothing.

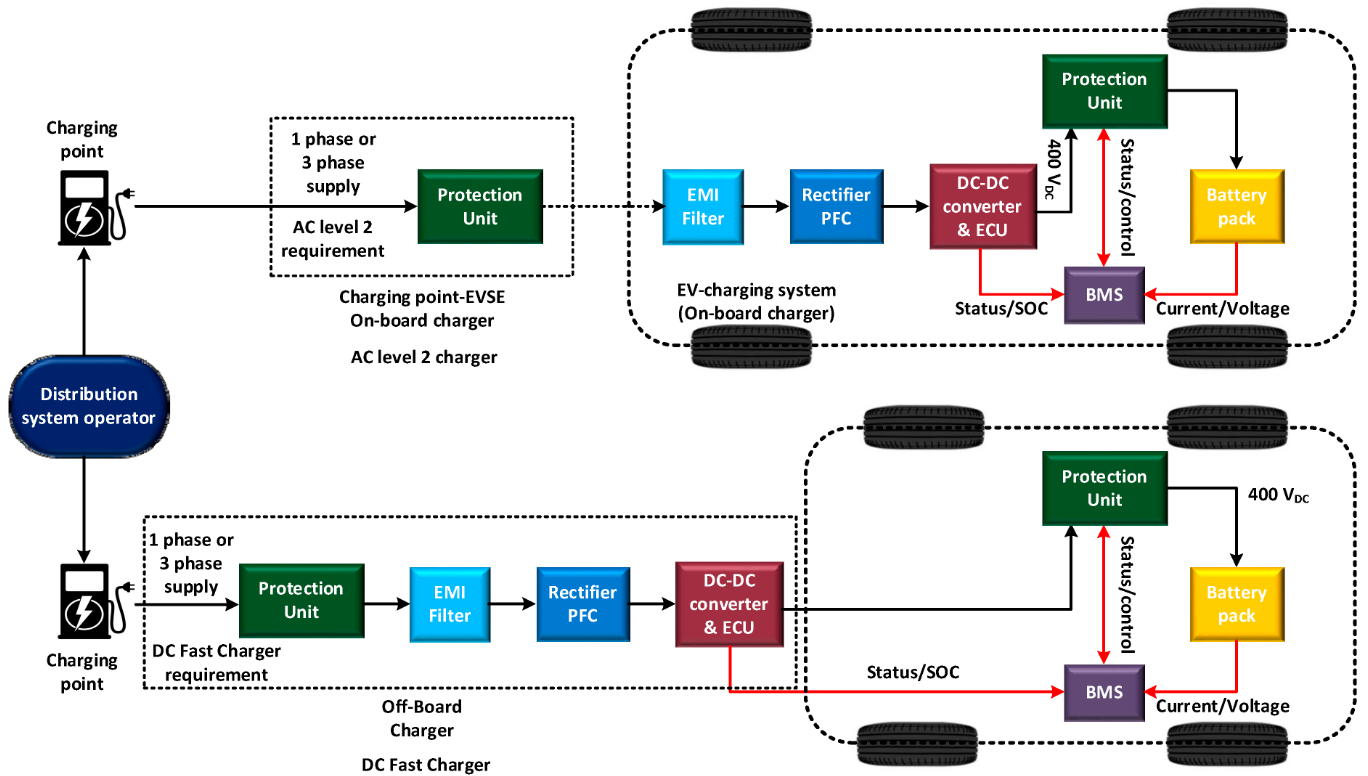

Finally, cheap quotes often exclude things buyers assume are included. The battery cabinet itself, yes. BMS, yes. But what about the power conversion system? The transformer? Grid protection equipment? Monitoring platform and software licenses? Installation and commissioning? Shipping? Some quotes include all of this. Some quotes include almost none of it. A 500 yuan per kWh quote that excludes PCS and installation versus a 900 yuan per kWh quote that includes everything turnkey aren't actually that far apart once you add the missing pieces.

Get a properly specified system with first-tier cells from manufacturers like CATL, BYD, or EVE Energy. Active balancing BMS. Liquid cooling for outdoor installation. Real certifications (more on this below). From a supplier with financial stability to honor warranty claims a decade from now. Suddenly the price is 1,200-1,500 yuan per kWh for domestic Chinese projects. Still cheap by global standards. Not the headline-grabbing numbers that show up in industry reports.

What Drives the Cost Structure

The conventional breakdown allocates roughly 40-50% of system cost to cells, 5-8% to BMS, 8-12% to thermal management, 15-20% to power conversion equipment, and the remainder to enclosure, wiring, safety systems, and miscellaneous balance of system components.

These percentages roughly hold for large systems in the hundreds of kWh to MWh range. Smaller systems show different distributions because fixed costs get divided across less capacity. One BMS architecture serves a 50kWh system or a 500kWh system with similar complexity. One enclosure houses whatever capacity fits inside. Engineering, certification, sales overhead, project management, and logistics have substantial fixed components regardless of system size. Divide those fixed costs by 50kWh versus 500kWh and the per-kWh impact differs by an order of magnitude.

The more practically useful question is where suppliers cut costs to hit aggressive price points.

Cell sourcing offers the most obvious lever. Cells from CATL, BYD, EVE Energy, or CALB command premiums because these manufacturers operate at massive scale with tight quality control and provide traceability documentation for every cell batch. Trading companies in Shenzhen's Huaqiangbei electronics district or Dongguan's industrial zones source cells from dozens of smaller manufacturers at lower prices. Some of these cells are perfectly fine. Some are B-grade stock from first-tier manufacturers sold through back channels. Some are cells that failed first-tier QC and got remarked and resold. Without testing equipment and expertise, buyers can't easily distinguish these sources.

The price difference is meaningful. First-tier LFP cells traded around 0.35-0.40 yuan per Wh in late 2024. Second-tier and gray market cells went for 0.25-0.30 yuan per Wh. On a 100kWh system that's a 10,000-15,000 yuan difference in cell costs alone. Enough motivation for cost-focused integrators to source from wherever offers the best price.

BMS represents another cost-cutting opportunity. A sophisticated BMS with active balancing, full cell monitoring, multiple communication protocols, cloud connectivity, and proper safety features might cost 80-120 yuan per kWh. A basic BMS with passive balancing and minimal features costs 20-40 yuan per kWh. The difference in system reliability and longevity is substantial. The difference in procurement cost is also substantial enough to tempt integrators facing price pressure.

Active balancing circuits use DC-DC converters to shuttle energy from high-voltage cells to low-voltage cells. This works during charging and discharging, moves meaningful amounts of energy, and actually keeps cells balanced over thousands of cycles. Passive balancing uses resistors to bleed off excess charge from high cells, works only during charging end phases, moves tiny currents, and can't prevent cells from drifting apart over time. The cost difference might be 40-60 yuan per kWh. The performance difference over a system's lifetime is much larger.

Thermal management offers similar cost-cutting potential. Liquid cooling systems with cold plates, circulation pumps, heat exchangers, coolant reservoirs, and control systems add 200-300 yuan per kWh over basic air cooling. For outdoor installations in hot climates or high-power applications requiring sustained output at 0.5C or above, liquid cooling pays for itself many times over through extended cell life and maintained performance. But the integrator selling a system with a three-year warranty and no performance guarantees might not value that long-term benefit. They pocket the thermal management savings and leave the buyer to discover the consequences years later.

Enclosure specifications affect cost as well. An IP65-rated outdoor enclosure with proper sealing, UV-resistant coatings, corrosion protection, and structural engineering for wind and seismic loads costs more than a basic sheet metal box. The difference might be 50-100 yuan per kWh for small systems where enclosure costs are a larger proportion of total cost.

Certification represents a cost that many buyers don't fully understand. A UL9540A-certified system has undergone extensive third-party testing for thermal runaway propagation. This certification is mandatory for most US commercial installations per NFPA 855 requirements. The testing process costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and takes months. That cost gets amortized across production volume, but for smaller manufacturers it can add meaningful cost per system. Uncertified systems are cheaper because they skip this process entirely. They're also almost unsellable in markets requiring certification, and may be uninsurable even in markets without formal requirements.

American Market Reality

Importing Chinese batteries into the US market involves navigating a tariff structure that keeps getting more complex. Section 301 tariffs on Chinese goods. Antidumping duties on specific battery categories. Countervailing duties to offset Chinese government subsidies. The exact rates depend on product classification and can involve substantial uncertainty, but effective combined rates often land in the 50-70% range. Additional tariff increases are scheduled for 2026.

The Inflation Reduction Act created tax credits intended to make domestic manufacturing competitive. The 45X manufacturing production credit provides $35 per kWh for battery cells manufactured in America and $10 per kWh for battery modules. Projects can also qualify for investment tax credits up to 30% with various bonuses for domestic content, energy community location, and prevailing wage compliance.

These credits help but don't close the gap entirely. Domestic US battery manufacturing capacity remains far below demand. The few operational US cell factories (mostly Korean-owned facilities built by Samsung SDI and LG Energy Solution) have costs 30-40% above Chinese factories even after IRA credits. Supply constraints mean US buyers often face long lead times and limited bargaining power.

Korean and Japanese battery manufacturers have moved aggressively into the US market to capture the opportunity created by China tariffs and IRA incentives. Their costs exceed Chinese competitors but their products qualify for IRA benefits and avoid the tariff burden. For many US buyers, Korean cells assembled in US facilities represent the practical path forward despite higher costs.

The net result: American buyers pay roughly double what Chinese buyers pay for equivalent systems. A system that costs 1,000 yuan per kWh installed in Guangzhou costs $250-300 per kWh installed in Texas. The gap reflects tariffs, logistics, higher labor costs, less developed supply chains, and the premium pricing that limited domestic supply enables.

European pricing falls between Chinese and American levels. Europe has no unified tariff barrier against Chinese batteries comparable to US Section 301 duties. Chinese systems can enter more freely, though trade tensions suggest this may change. But Europe also lacks China's manufacturing concentration, so logistics costs and local labor add meaningful expense. Typical installed costs run €200-250 per kWh for larger commercial systems, roughly 50-100% above Chinese domestic prices but well below American levels.

The 215kWh Standard Cabinet

One specific product configuration deserves detailed attention because it has become a de facto standard for commercial and industrial storage in China: the 215kWh outdoor cabinet.

This configuration (sometimes marketed as 200kWh, 215kWh, or 232kWh depending on manufacturer and whether they're quoting usable versus total capacity) pairs naturally with 100kW power conversion systems. The form factor fits standard shipping containers and installation footprints. Supply chains have optimized around this configuration with standardized components, established manufacturing processes, and competitive supplier networks.

Competition among manufacturers has driven prices for 215kWh systems remarkably low. Turnkey systems from reputable suppliers (first-tier cells, decent BMS, basic thermal management, installation, commissioning, and monitoring included) have dropped below 1,000 yuan per kWh in competitive bidding situations for larger project portfolios. That's the full system delivered and running, not just equipment FOB factory.

At that price point, commercial storage economics work in most Chinese cities with decent peak-valley electricity rate spreads. A facility paying 1.0 yuan per kWh during peak hours and 0.3 yuan during valley hours can cycle storage daily and achieve simple payback in four to five years at current system costs. The market has reached a point where storage is just economical for many applications rather than requiring subsidies or creative financial engineering.

The same basic 215kWh cabinet configuration sells for $200-280 per kWh equipment cost when exported to other markets, plus another $50-100 per kWh for shipping, import duties (where applicable), local installation, and commissioning. Total installed cost outside China but excluding the US market usually lands around $280-400 per kWh depending on destination and project specifics.

For US buyers, the same equipment faces tariff barriers that push total costs to $400-500 per kWh or higher. The tariff math makes Chinese-origin equipment increasingly uncompetitive versus Korean alternatives manufactured in US facilities that qualify for IRA credits.

Common Misconceptions

Several beliefs circulate in the industry that deserve pushback.

Cycle life numbers are often misleading. Manufacturers quote impressive figures like 6,000 or 8,000 cycles at 80% depth of discharge to 80% state of health. These numbers come from accelerated lab testing under controlled conditions: constant temperature, consistent cycling patterns, optimal charge and discharge rates. Real-world operation involves temperature fluctuations, variable load profiles, extended periods at high or low state of charge, and other factors that accelerate degradation. Prudent planning assumes real-world cycle life at 60-70% of laboratory claims.

Warranty terms require careful reading. A "ten-year warranty" could mean many different things. Does it guarantee a specific capacity retention (like 70% or 80% of original capacity at year ten)? Does it cover parts only or labor as well? What proof of proper operation does the manufacturer require to honor claims? Are there exclusions for temperature exposure, cycling patterns, or other operational factors? And perhaps most importantly: will the company still exist in ten years to honor any claims? Warranty terms that look similar on the surface can differ dramatically in actual value.

Installation costs get underestimated outside of mature markets. In China, where hundreds of thousands of storage systems have been installed, soft costs have been optimized through experience. Permitting processes are established. Utility interconnection procedures are routine. Qualified installation crews are abundant. Costs for these activities have dropped to maybe 50-100 yuan per kWh as part of turnkey system pricing.

In markets with less deployment experience, these soft costs remain high. Grid interconnection in the US can involve months of utility review, expensive studies, and potentially required infrastructure upgrades that add $30-100 per kWh to project costs. Permitting in some jurisdictions requires fire department approval, AHJ inspections, and engineering reviews that add time and money. Finding qualified installation crews may require paying premium rates or bringing crews from other regions.

Efficiency losses compound over time. Round-trip efficiency of 85-90% means 10-15% of stored energy disappears during each charge-discharge cycle. This seems like a small number until you compound it over thousands of cycles over a decade. A system cycling daily with 87% efficiency versus one with 92% efficiency will waste several hundred additional MWh over ten years. At even modest electricity prices, that efficiency difference represents real money that can justify somewhat higher upfront costs for more efficient equipment.

Energy density doesn't matter for stationary storage. This seems obvious but bears repeating because many discussions conflate EV battery requirements with stationary storage requirements. Electric vehicles desperately need high energy density because battery weight affects vehicle range and performance. Stationary storage systems sit in cabinets or containers with no constraints on weight or size beyond what the site can accommodate. The LFP chemistry that dominates stationary storage offers roughly half the energy density of NMC chemistries used in many EVs. For stationary applications, this doesn't matter. What matters is cost per kWh, cycle life, safety, and reliability. LFP wins on all of these metrics.

Price Trajectory

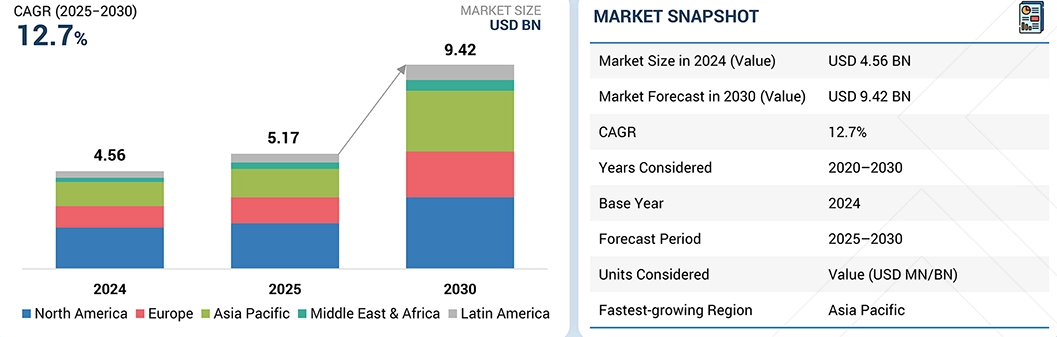

BloombergNEF and other forecasters project battery pack prices continuing to decline, reaching around $80 per kWh by 2030. That would represent another 30-40% reduction from 2024 levels.

Whether forecasts prove accurate depends on factors beyond anyone's ability to predict with confidence. Lithium carbonate prices collapsed from over $80,000 per ton in late 2022 to under $15,000 per ton by late 2024, driving much of the recent cell price decline. Further raw material cost reductions may be harder to achieve now that prices have fallen closer to production costs. Chinese manufacturing overcapacity currently suppresses prices but will eventually rationalize through consolidation and bankruptcy. Technology improvements continue but the easy efficiency gains from manufacturing process optimization got captured over the past decade.

The safe assumption is that prices will continue declining but more slowly than during the 2020-2024 period. Anyone delaying projects waiting for dramatically lower prices should consider that the opportunity cost of waiting (lost energy savings, delayed revenue) may exceed the value of future price declines.

LFP chemistry dominates stationary storage and this won't change anytime soon. LFP costs 30% less than NMC chemistries while offering longer cycle life, better safety characteristics, and superior performance at high temperatures. NMC's only advantage is energy density, which doesn't matter for stationary applications. Market share data shows LFP exceeding 90% of new stationary storage installations globally.

Sodium-ion battery technology has generated significant attention as a potential alternative. Chinese manufacturers including CATL and BYD have announced sodium-ion products and production capacity. Sodium-ion offers advantages in low-temperature performance (works down to -40°C versus LFP's struggles below -20°C) and eliminates lithium supply chain dependencies. Current sodium-ion costs exceed LFP by roughly 10-15%, limiting adoption to niche applications. Manufacturers claim they'll achieve cost parity by 2027. If that happens, sodium-ion could capture meaningful market share in cold-climate applications and provide supply chain diversification. For current projects, waiting for sodium-ion makes little sense given uncertainty around cost and timing.

Reference Pricing

Late 2024 and early 2025 market conditions, with appropriate caveats about rapid market changes:

Chinese domestic market, small systems 10-50kWh: 800-1,500 yuan per kWh installed depending heavily on configuration and supplier tier. The wide range reflects differences between basic systems with B-grade cells and passive BMS versus properly specified systems with first-tier components.

Chinese domestic market, mid-size systems 50-215kWh: 900-1,400 yuan per kWh for turnkey installations from reputable suppliers using first-tier cells. Competitive bidding situations for larger portfolios can push prices below 1,000 yuan per kWh.

Chinese domestic market, large systems and containers 500kWh+: 700-1,000 yuan per kWh equipment cost with installation adding another 50-150 yuan per kWh depending on site complexity. Very competitive situations and strategic bids from manufacturers seeking reference projects can go lower.

Export to non-US markets: Add 30-50% to Chinese domestic prices for logistics, margin, and certifications. A system at 900 yuan per kWh domestically might land at 1,200-1,400 yuan per kWh ($160-190) delivered to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, or Africa. European destinations usually add more due to higher logistics costs and local installation labor.

Export to US market: Roughly double Chinese domestic prices after accounting for tariffs and the complications of domestic content requirements for IRA credit eligibility. A 1,000 yuan per kWh domestic Chinese system translates to $300+ per kWh in the US market.

Scale effects: Moving from 50kWh to 500kWh system sizes cuts per-kWh costs by roughly 40-50% due to fixed cost amortization. Moving from 500kWh to 5MWh cuts costs another 20-30%. The relationship isn't perfectly linear and varies by supplier and configuration, but scale gives meaningful bargaining power.

Regional installed cost benchmarks: China at $85-125 per kWh represents the global floor. Southeast Asia, Middle East, and Africa usually range $150-200 per kWh. Europe runs $200-280 per kWh. The US remains the most expensive major market at $250-350 per kWh for comparable systems.

Thinking About the Purchase Decision

Anyone researching industrial lithium battery cabinet costs presumably wants to answer a practical question: does a specific project make economic sense at current prices?

That question doesn't have a generic answer. Project economics depend on electricity rate structures, demand charge profiles, available incentives, site-specific installation costs, required reliability levels, and risk tolerance around supplier selection. A project that generates strong returns in one context might be uneconomic in another.

What can be said with confidence: pricing has dropped far enough that storage makes economic sense for a much wider range of applications than even two or three years ago. Commercial and industrial facilities with significant peak-valley rate spreads or demand charges can often achieve simple payback in four to six years at current prices. Grid-scale projects bid into competitive markets at prices that would have seemed impossible in 2020.

The floor hasn't been reached. Prices will likely continue declining. But they've fallen far enough that waiting for further declines increasingly costs more in missed opportunity than it saves in equipment prices. For projects that pencil out at current prices, execution risk and opportunity cost of delay usually outweigh potential savings from waiting.

The harder challenge is navigating a market where products with the same nominal specifications can differ by 3x in price and far more than that in actual quality and value.

Understanding what drives those differences, specifying requirements appropriately, and identifying suppliers who will deliver quality and remain in business for warranty support matters more than finding the absolute lowest price. Cheap systems that fail early or underperform their specifications cost more in the long run than properly specified systems from reliable suppliers at higher initial prices.

That's the real answer to the cost question: the right price depends on matching specifications to requirements and finding competitive pricing within the appropriate quality tier, not just minimizing the initial quote.