A production line at CATL's Fujian factory produces 12 units of 5MWh container systems daily. These systems are shipped worldwide, and the numbers on the spec sheets are almost identical. But there's one detail rarely mentioned: when Australian customers inspect the factory, they stay for five days in the workshop, with a sampling rate three times higher than domestic customers. Most domestic customers come for half a day, tour the production line, take some photos, sign the contract, and leave.

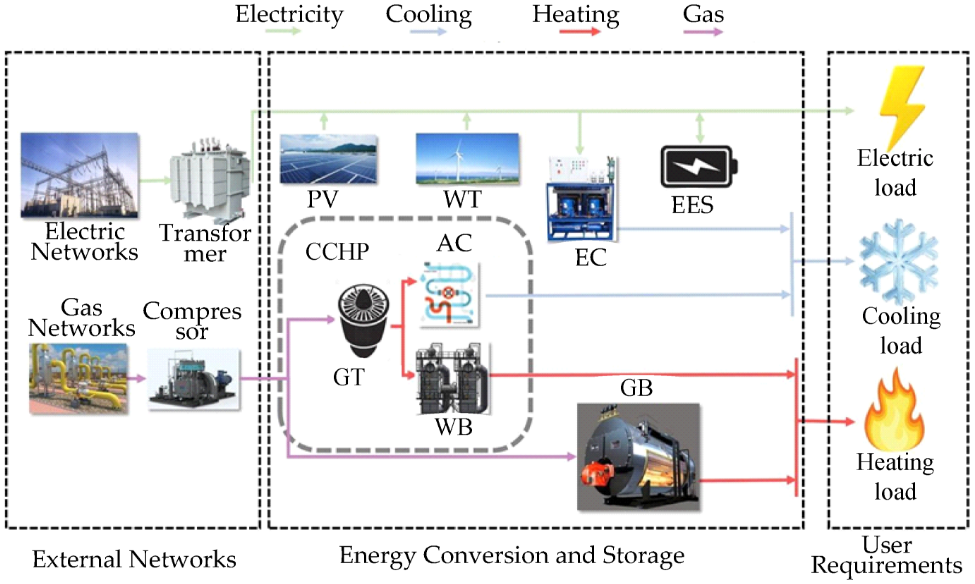

From a physical standpoint, container energy storage is simply stuffing batteries into a shipping container. A standard 20-foot container is 6 meters long, 2.4 meters wide, and 2.6 meters tall, containing batteries, inverters, air conditioning or liquid cooling units, fire suppression equipment, and a bunch of sensors and cables. Total weight is roughly between 25 and 35 tons, depending on how many batteries are packed inside.

There's nothing magical about this form factor itself. Shipping containers are the world's most mature logistics standard—any port can handle them, any truck can transport them. Putting energy storage systems into containers solves deployment efficiency problems, not some technological innovation.

Container Battery Storage

The real question is: why do some containers sell for 1.5 million yuan while others sell for 3 million?

Energy storage system integration companies founded around 2022 mostly followed the same model: buy cells from CATL, buy BMS from Keliyuan or Gotion, buy inverters from Sungrow or Kehua, get a sheet metal factory to custom-make the enclosure, hire a few engineers to stuff everything inside, get it working, and you can sell it. Technical barriers? None. Capital barriers? A few million yuan gets you started. So in 2023, hundreds of companies suddenly emerged, all calling themselves energy storage system integrators.

The problem is, the trouble starts after the product is sold.

Batteries sitting in a warehouse won't cause problems, but once they start being used, all kinds of issues emerge. Some project sites have high grid fluctuations, causing frequent inverter protection trips—several times a day. Some project locations are extremely hot in summer, and air cooling simply can't control the temperature, leading to rapid battery degradation. Other projects have loads with harmonics that cause the BMS to misjudge, resulting in unexplained shutdowns.

These problems are beyond the capability of assembly-type integrators to handle. Because they're just putting other people's components together without truly understanding how these things work. When problems arise, they can only go to suppliers, and suppliers say it's an integration issue—a game of passing the buck, and ultimately the customer blames the integrator.

There's a saying that's spread widely in the industry: energy storage isn't an assembly business, it's an operations and maintenance business. Whoever can keep the system running stably for ten years is the one who can actually make money.

So what exactly is container energy storage? A more accurate definition is: a complex electromechanical system that needs to operate continuously and stably over a time horizon of more than ten years.

What does ten years mean? Ten years ago, the iPhone 6 had just been released, WeChat didn't have mini-programs yet, and Tesla had only sold 30,000 Model S units. What the grid will look like in ten years, what percentage of renewable energy there will be, how electricity prices will change—nobody knows. But energy storage systems must continue working and generating returns in this unknown future.

This is why leading manufacturers can charge twice as much as small factories and still find buyers. It's not because the numbers on the spec sheet look better, but because buyers need to believe: this company will still exist in ten years, and there will be someone to handle problems.

For a 5MWh system, cell costs are roughly 2 million yuan, so CATL is essentially issuing a 2 million yuan credit guarantee to each customer. Only companies with sufficiently robust balance sheets dare make such commitments. Small factories making such promises are meaningless—whether the company will even exist in five years is uncertain.

The Investment Perspective

The logic of investment circles looking at energy storage projects is quite interesting.

Technical specifications? Basically ignored. Because everyone's paper specs are similar, and financial investors don't really understand what those specifications actually mean anyway. What they look at are a few simple things: who supplies the cells, how many years the system integrator has been in business, whether electricity pricing policies at the project location are stable, whether there are long-term power purchase agreements or capacity lease contracts locking in returns.

The biggest risk for energy storage projects isn't technical risk—it's policy risk. When Guangdong adjusted electricity prices in 2025, peak-valley spreads shrank by over 20%, and a batch of projects saw their returns drop from double digits to single digits. Against something like this, no amount of technical excellence helps.

Investment decisions in energy storage

Institutional capital now prefers investing in grid-side frequency regulation projects. While frequency regulation returns also fluctuate, at least they're market-priced—prices are determined through competition, which is more predictable than government-set electricity prices. Plus, frequency regulation projects usually involve grid companies, so there's someone to backstop if things go wrong. Commercial and industrial energy storage projects—those B2B ones—have dispersed customers, long payment cycles, and the worry that customers might disappear. Capital providers don't want to touch those.

The Technical Reality

Let's talk about some technical stuff.

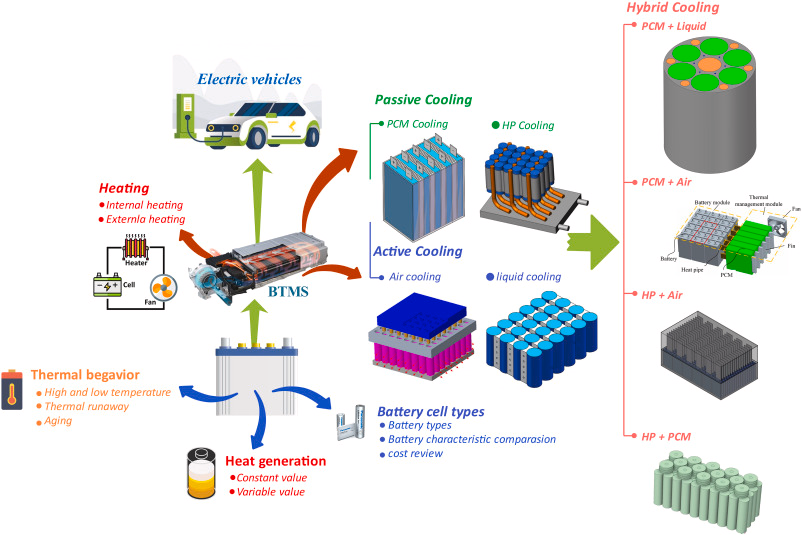

The most expensive component in a container energy storage system is the battery, accounting for 60-70% of total cost. But the most important component isn't the battery—it's the BMS and thermal management.

The battery itself is a fairly passive thing. The working principle of lithium batteries is taught in middle school chemistry: during charging, lithium ions move from the cathode to the anode; during discharging, they move back from the anode to the cathode. This process generates heat, causes losses, and the battery's state gradually changes with charge-discharge cycles. But the battery won't tell you what state it's in—it just works silently until one day it suddenly has problems.

The BMS's role is to make the battery observable. By measuring the voltage and temperature of each cell, the BMS calculates the battery's state of charge, state of health, available power, and so on. This information determines how much the system can charge, how much it can discharge, and when it should stop to protect itself.

But whether the numbers the BMS calculates are accurate—that's a big question.

Voltage and temperature are directly measured; as long as the sensors aren't broken, the numbers are accurate. But state of charge (SOC) is calculated, and accuracy depends on the algorithm. Lithium iron phosphate batteries have an annoying characteristic: in the middle SOC range, voltage barely changes. From 20% to 80%, voltage only changes by a fraction of a volt. Judging SOC by voltage produces terrifyingly large errors.

So BMS uses various methods to improve estimation accuracy: current integration, equivalent circuit models, Kalman filtering. Some BMS can control estimation error to within 3%; others can't even stay within 5%. That 2% difference .

Huawei's BMS leads peers by about two years in this regard. The core technology is Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): applying small current perturbations at different frequencies to the battery, measuring impedance response, and extracting internal battery state information from the response curves. This technology was previously only used in laboratories; Huawei was the first to turn it into a mass-production solution. Through EIS, Huawei's BMS can not only calculate SOC but also identify micro-short circuits inside cells and precursors of lithium plating. The system can issue warnings 6 to 24 hours before a cell actually develops problems.

What's this capability worth? In 2023, an energy storage station fire in California burned for three days, with direct losses plus cleanup costs exceeding $20 million. Post-incident investigation showed that the cell that caught fire had exhibited impedance anomalies 48 hours before thermal runaway, but the BMS at the time didn't have this monitoring capability.

Thermal Management: The Hidden Differentiator

The importance of thermal management is easily underestimated.

Batteries fear heat—that's common sense. But batteries fear temperature differences even more. A battery cluster contains over a hundred cells; if some cells are at 35°C while others are at 28°C, their degradation rates are different. The hotter ones will age first, and after a year or two, they become the weak link of the entire cluster. The system's capacity is dragged down by those worst cells, while the capacity of other cells is wasted.

This is why liquid cooling is a must for high-cycle projects. Air cooling's temperature difference control is limited—7-8°C temperature differences are normal. Liquid cooling can compress this to 2-3°C; top-tier solutions can achieve just over 1°C. This difference might not be visible in the first year, but it becomes very apparent after three to five years.

liquid cooling systems can compress temperature differentials to just over 1°C

Sungrow's PowerTitan system deployed in the Middle East in 2024 has a set of measured data: with outdoor temperature at 45°C and the system continuously charging and discharging at 1C, the highest cell temperature was 32°C. At the same project, another supplier's competing product had cell temperatures reaching 41°C—a 9°C difference. How much capacity difference will this 9°C become after three years? Conservative estimate: over 10%.

The downside of liquid cooling is complexity. Coolant can leak. Pipes can clog. Pumps can fail. In 2023, there was a major project where the quick-connect fitting seal on a coolant pipe aged and cracked, leaking over a hundred liters of coolant and scrapping the entire battery cabin. That seal ring's procurement cost was about 5 yuan.

After this incident, leading manufacturers basically all switched to welded pipes. But welding requires much higher skill from on-site construction workers, increasing training and quality inspection costs.

Safety: A Topic Not Easy to Write About

Safety is a topic that's not easy to write about.

For energy storage station safety incidents, the media likes to use the word "explosion." But the real situation is that pure explosions are rare; most incidents are fires triggered by thermal runaway, then combustible gases from the fire accumulate in enclosed spaces, and finally get ignited causing deflagration.

The investigation report on the 2019 Arizona McMicken energy storage station incident (published by DNV GL, over 100 pages) gave the core conclusion: combustible gases released after battery thermal runaway accumulated inside the enclosed cabin; when firefighters arrived and opened the cabin door, fresh air from outside rushed in, bringing gas concentration right into the explosive limit range, and then it exploded. Four firefighters were injured.

This incident changed the entire industry's safety design thinking. Current energy storage containers all have forced ventilation designs, continuously extracting air during operation to prevent combustible gas accumulation. At the same time, the cabin must have pressure relief panels, so if deflagration occurs, pressure is released through the relief panels instead of blowing the entire cabinet apart.

Fire suppression for energy storage stations is different from building fire suppression. When a building catches fire, spraying water works. When batteries catch fire, spraying water doesn't necessarily work—sometimes it makes things worse. Because lithium batteries at high temperatures release oxygen and can burn without external air. Some energy storage stations' fire suppression strategy is: don't extinguish the fire, just prevent spreading, let the burning module burn itself out.

This sounds counterintuitive, but it might be the most pragmatic approach.

The Market Reality

Finally, let's talk about the market.

2024 is a turning point for the energy storage industry. In previous years, as long as you could produce a system, someone would buy it. Even rising cell prices weren't feared because downstream demand grew faster than supply. Starting in 2024, things are different—cell prices dropped over 50%, system prices dropped 40%, demand growth slowed, and overcapacity became very apparent.

In 2024, China's energy storage cell production capacity exceeded 500GWh, with actual shipments around 200GWh (GGII data). This means the industry average capacity utilization is under 40%. More than half of production lines are sitting idle.

In this oversupplied market, price wars are inevitable. By the end of 2024, system average prices in bids had fallen to just over 0.5 yuan per Wh, with some bids in the 0.4 range. At these prices, system integrators' gross margins are only single digits—after deducting various expenses, basically no profit. What is everyone betting on? Betting that they can survive until industry consolidation ends, betting that competitors will collapse first.

2025 will be even more brutal. Large amounts of new capacity are still coming online, and there's no sign of explosive growth on the demand side. The industry's prediction is that if half the companies can survive by year-end, that would be good.

Who can survive? Those who make their own cells have cost advantages—they can survive. Those who sell well overseas have larger profit margins—they can survive. Those with state-owned enterprise backgrounds aren't afraid of losses—they can survive. The rest—those purely doing assembly, those surviving on a few orders—are in trouble.

The Answer

Now we can answer the question from the beginning.

What is container energy storage?

It's a battery energy storage system installed in a standard shipping container. That's the physical definition.

It's an asset that needs to operate continuously and stably over a time horizon of more than ten years, continuously generating returns. That's the commercial definition.

It's a chip for betting your life in a market with severe oversupply, rapidly falling prices, and rapid industry consolidation. That's the 2025 industry definition.

Container Battery Storage

For end users who want to buy energy storage systems, the selection criteria are actually simple: choose a supplier that will still exist in ten years. You don't need to look at specs, prices can be negotiated, but this cannot be compromised. Because energy storage isn't a one-time transaction—it's a relationship lasting more than ten years. Starting a ten-year relationship with a partner who might disappear is unwise.

For those who want to enter this industry, now might not be a good time. Unless you have something others don't—either truly leading technology, or indispensable channels, or deep enough pockets—entering the arena just means filling holes.

The Bottom Line

This is the true face of container energy storage in 2025. Not some sexy new energy concept—it's a war of attrition of capital and endurance.