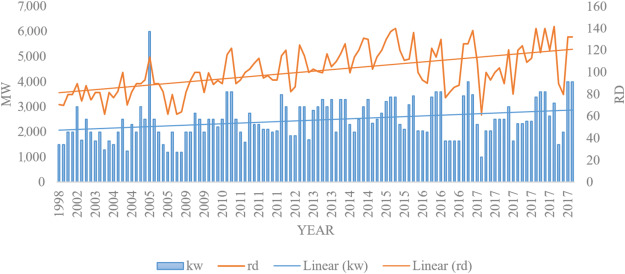

How to Size a Battery Bank for a Solar System

The Rating Game

That 200Ah battery sitting in the warehouse? It was tested at 77°F, discharged at a leisurely 10 amps over 20 hours, fresh off the production line. Your garage hits 15°F in January. Your well pump pulls 80 amps when it kicks on. The battery is three years old.

Under those conditions, you might get 90Ah out of it. Maybe less.

Temperature alone murders capacity. Every degree below 77°F costs you roughly 1% of rated capacity. Do the math for a cold climate and you need nearly twice the nameplate just to break even on temperature. I've seen guys in Minnesota spec out beautiful systems on paper that couldn't make it through a single January night because they used summer numbers. They'd wake up at 3am with dead batteries, frozen pipes threatening to burst, and a very expensive lesson learned.

The physics isn't complicated. Sulfuric acid gets thick when it's cold. Thick electrolyte means ions crawl instead of run. The chemical reaction that moves electrons in and out of the plates slows down, and the battery's ability to deliver current drops off a cliff. At -20°F the electrolyte turns into something closer to syrup than liquid, and the battery barely functions regardless of how charged it is.

But cold is at least predictable. You know winter is coming. You can plan for it. Heat is sneakier.

Batteries in hot climates actually gain a little capacity. A battery at 95°F might deliver 102% of its rating. But here's what the spec sheets don't tell you: that extra 2% costs you about two years of lifespan. Heat accelerates every bad thing that happens inside a lead-acid battery. Grid corrosion speeds up. Water evaporates faster. The positive plate paste softens and sheds. Every 15 degrees above 77°F roughly halves the battery's life expectancy.

A battery rated for 7 years at room temperature might last 3 years in a shed that averages 100°F through summer. I've seen black metal battery boxes in Arizona that hit 150°F inside on sunny days.

Batteries in those boxes were toast within 18 months regardless of how well the rest of the system was designed. All that careful sizing work meant nothing because nobody thought about where the batteries would actually live.

And then there's discharge rate. This is where it gets ugly.

Peukert figured this out back in 1897 and published a paper that nobody in the solar industry seems to have read. The faster you drain a lead-acid battery, the less total energy you get. Not a little less. A lot less. And it follows an exponential curve, not a straight line.

A 200Ah battery at 10 amps discharge gives you pretty close to 200Ah. The rating is honest at that rate because that's exactly how it was tested. But crank the discharge up to 100 amps and you might only get 95Ah. At 200 amps you're looking at 60-70Ah if you're lucky. Same battery, same state of charge, wildly different usable capacity depending on how hard you hit it.

The reason involves diffusion limits. Ions moving through electrolyte have a maximum speed. Pull current faster than ions can migrate to replenish the reaction zones, and the voltage drops even though plenty of chemical energy remains in the plates. The battery doesn't know it still has juice. The voltage sags, the inverter sees a dead battery, and the system shuts down with 30-40% of the energy still locked inside.

This is why systems sized on paper die in the field. Somebody calculated average daily load at 50Ah, bought a 200Ah battery thinking they had four days of backup, and then watched it face-plant the first time the well pump, fridge, and freezer all cycled together. The instantaneous load spiked to 150 amps, Peukert kicked in, and suddenly that "four day reserve" became six hours. The batteries weren't undersized for the average load. They were undersized for the peak load, and nobody bothered to think about that.

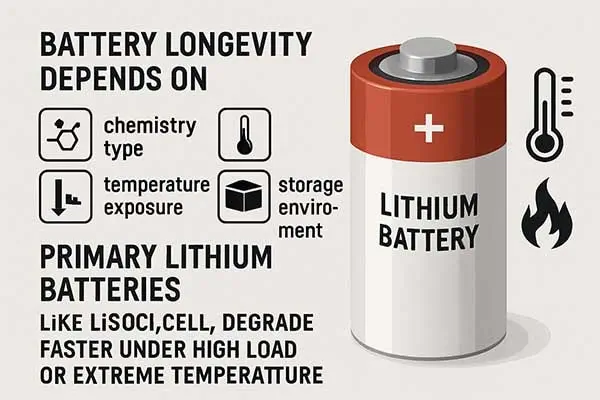

Lithium doesn't care about discharge rate. The Peukert exponent for lithium iron phosphate sits somewhere around 1.02-1.05, close enough to 1.0 that it barely matters. Pull 50 amps or 200 amps from a lithium pack and you get basically the same total energy out. This changes the sizing math dramatically. A lithium bank sized for average load actually delivers that capacity under real-world surge conditions. Lead-acid needs headroom for Peukert. Lithium doesn't.

There's a catch with lithium in cold weather though. Unlike lead-acid, which works poorly but still works below freezing, most lithium chemistries cannot charge below 32°F without damage. Charging a cold lithium cell causes lithium metal to plate out on the anode instead of intercalating properly into the graphite. That plating is permanent damage. Do it enough and you get dendrites that can pierce the separator and cause internal shorts. The BMS on any decent lithium pack will refuse to charge below freezing for exactly this reason.

So cold-climate lithium installations need heated battery enclosures. The heater has to run before charging starts, which means either battery power to run the heater (reducing net capacity) or an external power source to warm things up. It's not a dealbreaker but it's a complication that lead-acid doesn't have.

Depth of Discharge is Not a Suggestion

50% DoD for lead-acid isn't conservative engineering. It's survival.

I know the spec sheets say you can go to 80%. I know the guy on the forum ran his at 70% for two years and says it's fine. He's either lying about the depth or he's about to find out why battery warranties have so many asterisks in the fine print.

The sulfation thing isn't complicated. When you discharge a lead-acid battery, lead sulfate crystals form on the plates. That's the actual chemistry of discharge. Small crystals dissolve back into the acid during charging and reconstitute into active material. Big crystals don't dissolve as easily. Really big crystals don't dissolve at all.

Deep discharge grows big crystals. Leave a battery sitting at low state of charge and those crystals harden through recrystallization. Once they harden, they're permanent. They take up space on the plate surface without contributing to capacity. Every deep cycle converts a little more active material into inert sulfate. The battery gets weaker each time.

At 80% DoD, expect 200-300 cycles before the battery is junk. At 50%, you might see 800 cycles. At 30%, some batteries hit 1500 cycles. Telephone company batteries designed for 20% DoD can reach 2500+ cycles because that's what you need when you're maintaining 50,000 battery strings across a metropolitan area and you don't want to be replacing them constantly.

The math on which depth is cheapest depends on upfront cost versus replacement cost versus how much you hate working on battery banks. Most people land on 50% as the practical limit. You get half the rated capacity as actually usable capacity, which sounds wasteful until you realize the alternative is buying new batteries every 18 months instead of every 6 years.

Going shallower than 50% rarely pencils out for residential systems. The cycle life curve flattens below 50%. You gain fewer extra cycles per percentage point of additional protection. Meanwhile, battery costs scale linearly with capacity. The sweet spot where the curves cross typically lands right around 50% DoD.

Lithium plays a different game. The chemistry doesn't sulfate. There's no crystal formation problem because the lithium-ion mechanism works differently. Ions shuttle between cathode and anode without forming crystalline intermediates that might resist reversal.

You can bang on lithium at 80% DoD and get 3000+ cycles out of quality cells. Some manufacturers rate their cells for 5000 cycles at 80% DoD. Drop to 60% and you might add another thousand cycles. The improvement exists but it's nowhere near as dramatic as lead-acid. Going from 80% to 50% DoD on lithium might extend cycle life from 4000 to 5500 cycles. Going from 80% to 50% on lead-acid extends it from 300 to 800 cycles. Different math entirely.

This is why lithium banks end up half the size of lead-acid for the same usable capacity. You get 80% of nameplate usable versus 50%. That's 60% more usable energy per rated amp-hour before you even start counting the efficiency differences.

Load Calculations Lie

Everyone underestimates their loads. Everyone.

The worst offenders are the spreadsheet guys. They list every appliance with its nameplate wattage, multiply by hours of use, add it up, and get a number that has almost no relationship to what actually happens when they flip the switch.

Refrigerators don't run 24/7. The compressor cycles. A fridge rated at 150 watts might average 40-50 watts over a full day, depending on ambient temperature, how often the door opens, and how full it is. An empty fridge in a hot garage runs way more than a full fridge in an air-conditioned kitchen. The nameplate tells you nothing useful about actual consumption.

Air conditioners are worse. That 1500 watt unit might pull 1500 watts at startup and when it's 110°F outside and you're asking for 70°F inside. On a mild day with the unit cycling on and off, it might average 300-400 watts. Which number goes in your spreadsheet? The nameplate? The average? The worst case? Wrong answer costs you money either way.

Electric water heaters throw another curveball. A 4500 watt heater doesn't run 4500 watts continuously. It heats up, shuts off, sits there losing heat slowly, and fires again when the temperature drops below setpoint. Daily consumption depends on how much hot water you use, inlet water temperature, tank insulation, and thermostat setting. Could be 3 kWh/day, could be 15 kWh/day. The nameplate tells you exactly nothing.

Phantom loads are the silent killers. Every wall wart plugged in with nothing attached to it. Every device on standby waiting for a remote signal. Every smart home gadget sitting there sipping power 24/7 waiting for someone to talk to it. 5 watts here, 10 watts there, 3 watts from that thing you forgot was even plugged in. Adds up to 50-100 watts of continuous draw in a typical American house. That's 1.2-2.4 kWh per day doing absolutely nothing useful. Most people don't even know these loads exist until they kill the main breaker and walk around with a meter.

The only way to get real numbers is to measure. Clamp meter on the main panel for a month, preferably during peak season. Or one of those whole-house monitors that clips onto the mains. Log everything, then look at the actual data.

Use the worst day, not the average. Your battery doesn't care what your average day looks like. It needs to survive the worst one. If your average is 12 kWh but one day spiked to 18 kWh because you ran the shop tools and the AC at the same time, size for 18.

The Autonomy Trap

Everybody wants a week of autonomy. Nobody wants to pay for it.

Here's the thing about autonomy days: the cost scales linearly but the benefit doesn't. Going from 2 days to 4 days doubles your battery cost. Going from 4 to 7 days nearly doubles it again. But how often do you actually get seven consecutive cloudy days? In most of the country, that's a rare event. Maybe once every few years. You're spending thousands of extra dollars to cover a scenario that might not happen.

At some point a generator becomes the smarter play. A decent propane generator runs $1000-2000 installed. A week of battery autonomy might be $15,000-30,000 in additional battery capacity depending on your load. The generator sits there for months or years doing nothing, burning nothing, costing nothing. When the extended cloudy stretch finally hits, it kicks in, runs a few hours to top off the batteries, and goes back to sleep. You burn maybe $20-50 in propane and life continues.

I've seen systems with three days of battery and a generator backup outperform systems with seven days of battery and no backup. Not in normal weather. They're equal in normal weather. But when the weird stuff happens, the three-day system has a backstop. The seven-day system just has more batteries to carry through a longer disaster.

Two days works for desert climates with reliable sun. Southern Arizona, the Australian outback, that kind of environment. Consecutive cloudy days are rare enough that two days covers nearly every realistic scenario. Three to four handles most temperate zones where clouds are common but extended overcast is not. The Pacific Northwest, Great Lakes region, Central Europe. Beyond four days, do the math on generator backup versus additional batteries. The batteries almost never win unless you have a specific reason to avoid generators entirely.

Off-grid fundamentalists hate generators. I get it. The whole point was to get away from burning stuff. But a generator that runs 20 hours per year costs almost nothing to operate and provides essentially unlimited backup capacity. Tens of thousands of dollars in extra batteries to avoid running a generator occasionally is an emotional decision, not an economic one.

Efficiency Losses Stack Up Fast

Between your solar panels and your light bulbs, energy disappears at every step. None of the conversions are free.

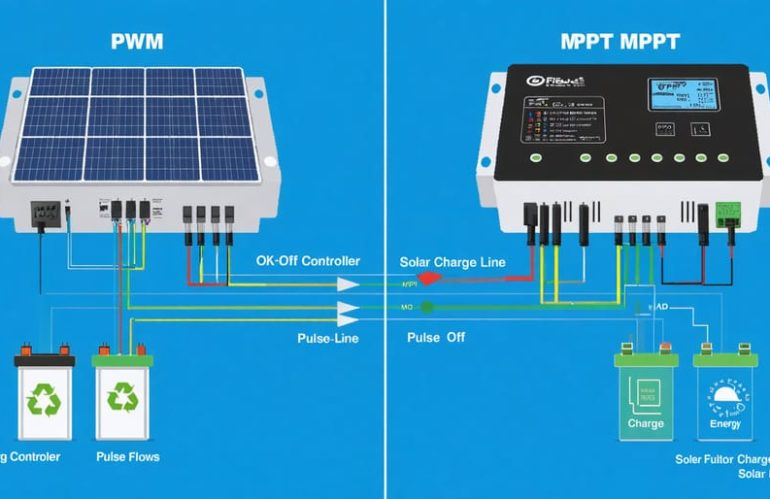

Charge controller: 3-5% gone for MPPT, more for PWM in mismatched setups. MPPT controllers convert high-voltage solar output down to battery voltage with reasonable efficiency. PWM controllers just chop the voltage without conversion, wasting the difference as heat. If your panels put out 30 volts and your battery wants 14 volts, PWM throws away over half the potential power. MPPT keeps most of it.

Battery charging efficiency: 15-20% gone for lead-acid, 5-8% for lithium. The difference comes from the charging algorithm. Lead-acid batteries need to be overcharged slightly to reach full state of charge. That last 15-20% of charge goes into gassing and heat rather than stored energy. Lithium cells accept charge more efficiently and don't require the same overcharge margin.

Battery discharge efficiency: another 3-5% to internal resistance. Current flowing through the battery meets resistance and generates heat. The loss is proportional to current squared, so high discharge rates waste more than low rates.

Inverter: 5-15% loss depending on load level. Inverters are most efficient around 50-75% of rated capacity. Run them at 10% capacity and the fixed losses (display, control circuits, transformer core losses) dominate. A 5000 watt inverter running a 200 watt load might waste 50-80 watts just being on, which is a 25-40% conversion loss at that load level. Size the inverter for actual loads, not worst-case capacity.

Wiring: 2-5% depending on how cheap you went on cable. Voltage drop in undersized wiring is just I²R losses, energy converted to heat instead of delivered to loads. The usual guideline is no more than 3% drop from battery to inverter on the DC side. Longer runs or higher currents need heavier cable.

Add it all up and 25-30% of generated energy never makes it to your loads in a lead-acid system. Lithium runs maybe 15-20% total losses because of better charging efficiency and lower internal resistance. Over a year, that 10% efficiency gap adds up. A 10 kWh daily load served by lead-acid needs about 13.3 kWh of solar generation to maintain state of charge. The same load served by lithium needs about 12 kWh. The difference means either more panels or smaller batteries.

The Actual Math

Alright, example time. Real numbers, all the adjustments included.

House uses 10 kWh/day. Measured over a month with a whole-house monitor, using the highest day as the design basis. Location gets cold in winter, call it 0°F minimum battery temperature. Owner wants three days autonomy because weather patterns usually break by then. Going with lead-acid because budget is tight and the owner knows how to maintain batteries.

Start with the daily load: 10,000 Wh.

Three days of autonomy: 30,000 Wh.

Efficiency adjustment. Lead-acid round-trip efficiency around 75% including all the charging and discharging losses: 30,000 / 0.75 = 40,000 Wh.

Depth of discharge at 50%: 40,000 / 0.50 = 80,000 Wh.

Temperature derating for 0°F. Capacity drops maybe 40% at that temp: 80,000 / 0.60 = 133,333 Wh.

Aging factor. Battery should still work at end of life, not just when new. Figure 80% capacity after 5-6 years of service: 133,333 / 0.80 = 166,666 Wh.

Call it 170 kWh of lead-acid capacity. At 48 volts nominal that's about 3,500 amp-hours.

That's a lot of batteries. Like, fill-a-room lot of batteries. A single golf cart battery is 6V 220Ah, so you'd need eight in series for 48V and that gets you 220Ah per string. Fifteen strings in parallel to reach 3300Ah. One hundred twenty individual batteries. They'll weigh around 4500 pounds total and take up about 60 square feet of floor space.

Now see why lithium looks attractive?

Same scenario with lithium. Better efficiency (85% round-trip because lithium charges more efficiently), deeper allowable discharge (80%), less temperature derating (assume heated enclosure keeps batteries above freezing, so only 10% capacity loss at cold edge), and longer life (design for 90% capacity at 10 years instead of 80% at 6 years).

10,000 × 3 / 0.85 / 0.80 / 0.90 / 0.90 = 55,000 Wh.

Call it 55 kWh. At 48V that's about 1,150 Ah. Less than a third of the lead-acid requirement.

A 48V 100Ah lithium module runs about 40kg. You need eleven or twelve of them. Total weight under 500 kg. Fits in a closet. No monthly maintenance. No watering, no equalization charges, no worrying about sulfation from missed charge cycles.

The lithium costs more per kWh upfront. Current prices run $200-300 per kWh for quality lithium iron phosphate versus $100-150 per kWh for lead-acid. But you need way fewer kWh, so total battery cost might actually be similar or lower. And you don't replace it twice during the system's lifetime.

Why Everything Runs on 48V Now

Quick aside on voltage because it matters more than people think.

A 5kW system at 12V pulls 417 amps at full output. That needs cables thick as your thumb and fuses the size of your fist. Voltage drop becomes a nightmare over any distance. A 10-foot cable run at 400 amps drops 0.5V even with 4/0 cable, which is over 4% loss and outside acceptable limits.

Same system at 48V pulls 104 amps. Normal wire sizes work. Standard fuses and disconnects handle it. Voltage drop stays manageable even on longer runs. You can put the batteries 30 feet from the inverter without heroic cable sizing.

The equipment situation seals the deal. Good luck finding a 5kW inverter that runs on 12V. They don't really exist anymore. The industry moved to 48V for anything serious because it's the only way to build high-power equipment with reasonable wire and component sizes. The 12V stuff maxes out around 2kW, serving primarily the RV and boat market where compatibility with 12V accessories matters more than efficiency.

24V sits in the middle and makes sense for some medium-sized systems. But new installations mostly go straight to 48V unless there's a specific reason not to.

Lithium battery modules ship in 48V configurations because that's what the market wants. The industrial supply chain (telecom, data centers, forklifts) runs on 48V and dwarfs the off-grid solar market. Building a 48V system from off-the-shelf modules costs less than cobbling together 12V or 24V equivalents from RV parts.

Matching Solar to Batteries

The solar array and battery bank need to work together. Too much solar and the batteries cook from overcharging. Too little solar and they never get full, which kills lead-acid through sulfation and throws off lithium BMS calibration.

For lead-acid, charging current should run 10-13% of amp-hour capacity. Below 5% and bad things happen. The battery never gets properly stirred. Electrolyte stratifies with heavy acid at the bottom and weak acid at the top. The plates charge unevenly. Sulfation sets in even though the battery thinks it's at full charge.

Above 20% charge current, gassing gets excessive. Water loss accelerates. Heat builds up. The batteries might accept the current but they won't last as long.

A 1000Ah lead-acid bank wants 100-130 amps of charge current. At 48V that's 4800-6200 watts of charging power. After accounting for controller efficiency and typical panel derating, you need 5500-7000 watts of panels to deliver that current reliably.

Lithium doesn't care nearly as much about charge rate. You can hammer lithium at 30-50% of capacity (0.3-0.5C) without damage. Most BMS units limit charge rate below the cell's actual tolerance to add margin, but even with BMS limits you're usually looking at 20-30% charge rates. A 1000Ah lithium bank might happily accept 200-300 amps of charge current, limited only by how much solar you can afford.

Energy balance matters more than current matching anyway. The array needs to produce enough daily to cover consumption plus all those efficiency losses plus some margin for cloudy days. Size for the worst solar month, not annual average, or watch your batteries slowly starve through winter.

A 10 kWh daily load with 25% total losses needs 13.3 kWh of solar generation to break even. In January at 40° latitude with 3 peak sun hours, that requires 4.4 kW of panels minimum. In July with 6 peak sun hours, those same panels generate 26 kWh and the excess goes to waste unless you have somewhere to put it. Size for the lean months and accept the surplus during the fat months.

The Stuff That Actually Kills Batteries

Temperature management matters more than sizing in a lot of installations. I've seen perfectly sized systems fail in three years because the batteries sat in a black metal box in direct sun. Internal temps hit 140°F on summer days. Lead-acid life halves for every 15°F above 77°F. Do that math and a seven-year battery becomes a two-year battery.

Shade the enclosure. Ventilate it. Paint it white. Insulate it if you're in a hot climate. Put batteries inside conditioned space if at all possible. A wall-mounted battery in a climate-controlled garage lasts twice as long as the same battery in an outdoor shed, all else equal. The extra installation cost pays back in battery life within a few years.

Battery quality varies wildly behind identical specifications. Two 200Ah batteries from different suppliers might actually deliver 200Ah and 140Ah respectively. The spec sheets both say 200Ah but the test protocols differ. One manufacturer tests at C/10, another at C/20. One uses optimistic temperature assumptions. One cherry-picks cells for rating tests.

Weight provides a sanity check for lithium batteries. Physics doesn't lie about energy density. Lithium iron phosphate cells run 150-180 Wh per kilogram of cell mass, varying by cell format and manufacturer. A 48V 100Ah pack claiming 4.8 kWh of capacity should weigh at least 27 kg of cells alone, plus 5-10 kg of casing, BMS, terminals, and wiring. Packs advertised at that rating but weighing under 30 kg almost certainly contain less capacity than claimed. The missing weight has to come from somewhere, and cells are most of the mass.

BMS quality on lithium packs ranges from excellent to fire hazard. The BMS handles cell balancing, charge limiting, temperature protection, and overcurrent shutdown. Get one of these wrong and you have problems ranging from poor performance to actual flames.

Cheap BMS units use passive balancing with currents under 50 mA. At that rate, equalizing a 5% imbalance across 100Ah cells takes over 100 hours of float time. Cells may never fully balance in systems that cycle daily without extended float periods. The imbalance grows over time until the weakest cell hits low-voltage cutoff while other cells still have juice. The pack shuts down with usable energy stranded inside.

Premium BMS units employ active balancing at 1-2 amps. Instead of burning off excess charge as heat, they shuttle energy from high cells to low cells. Balancing completes within each charge cycle regardless of imbalance magnitude. The cost difference between passive and active balancing BMS runs maybe $50-100 per pack. Worth every penny for any system expected to last more than a couple years.

Mixing old and new batteries creates a death spiral. Old batteries have higher internal resistance. In a parallel bank, current distributes based on resistance. Lower-resistance new batteries absorb more current during charging and deliver more during discharge. Higher-resistance old batteries contribute less and less.

The new batteries work harder to compensate, aging faster than they would in a matched bank. The old batteries receive less charge than they need, falling further behind. Within a year or two the mismatch becomes severe enough to trigger shutdowns with significant capacity stranded in the new cells that can't be accessed because the old cells drag down the bank voltage.

Add batteries to an existing bank only within the first six months while original cells are still close to new condition. After that, treat expansion as a separate parallel bank with its own charge management, or accept that replacement means the entire bank at once. Partial replacement makes the problem worse, not better.

What the Vendors Won't Tell You

The solar installer wants to sell you a system. The battery vendor wants to sell you batteries. Neither one gets paid for telling you that your project doesn't pencil out.

Oversizing is the safe play for vendors. Nobody ever got sued for selling too much battery. Undersizing leads to angry phone calls and warranty claims. So the industry defaults to conservative sizing with fat margins built into every calculation. That protects the vendor's liability but costs you money.

The opposite problem comes from the lowball guys trying to win competitive bids. They size to theoretical minimums using nameplate capacities, summer temperatures, and average loads. The system looks great on paper and costs 30% less than the competition. Three years later the batteries are dead and the lowball installer is out of business.

Find someone who will show their math. Real math, with temperature derating, Peukert adjustment, efficiency losses, and aging factors. If they can't explain where their numbers came from, they're either hiding something or they don't know themselves. Neither is good.

The warranty fine print matters more than the headline number. A ten-year warranty that excludes high temperatures, requires monthly equalization charges, and voids coverage for depths below 50% isn't worth the paper it's printed on if your installation doesn't match those conditions. Read the exclusions. Then read them again. Then think about whether your actual use case fits within those restrictions.

Battery prices fluctuate constantly. Lithium iron phosphate has dropped from $800/kWh to under $200/kWh in the span of five years. Lead-acid prices bounce with commodity markets. Get current quotes before finalizing any sizing decision because the optimal answer changes with pricing.

Chinese manufacturers have flooded the lithium market with cheap cells. Some are excellent. Some are rebranded rejects from Tier 1 suppliers. Some are outright dangerous. The problem is telling them apart before you install them in your house. Reputation matters. Buy from suppliers who stake their business on quality rather than price arbitrage.

What Actually Happens Over Time

Year one runs great. The batteries are new, capacity matches nameplate, everything works as designed. Owners get complacent.

Year three is when problems start showing up in lead-acid systems. Capacity has faded to 85-90% of new. Some cells are weaker than others. The owner notices the low-voltage alarm hitting earlier than it used to. If they're diligent about equalization and water levels, the system stabilizes. If they've been lazy about maintenance, the degradation accelerates.

Year five separates the well-designed systems from the marginal ones. A system sized with proper margins still works fine at 75-80% capacity. A system sized to minimums is already struggling. The batteries that sat in a hot shed are toast. The batteries that lived in climate control are still humming along.

Year seven is replacement time for most lead-acid installations. Even with perfect care, cycle life limits catch up eventually. Smart owners start budgeting for new batteries around year five. Dumb owners wait until the system dies at an inconvenient moment.

Lithium follows a different trajectory. Year one through year five shows minimal degradation if the BMS is doing its job. Maybe 5-10% capacity loss total. Year five through year ten continues the slow decline. Well-maintained lithium systems hit year ten with 80-85% of original capacity, which is end-of-life by warranty definitions but still perfectly functional for most uses.

The lithium systems I worry about are the ones with cheap BMS units and no monitoring. Cell imbalances accumulate silently. One day the pack just refuses to work. Opening it up reveals one cell group at 2.0V while the others sit at 3.2V. That damaged cell group has been getting hammered for years while the BMS claimed everything was fine. Premium BMS with cell-level monitoring catches this stuff before it becomes catastrophic.