How Big of a Battery Bank Do You Need to Run a House?

Somewhere between 10 kWh and 200 kWh. That range is so wide it tells nothing useful.

The short answer is that nobody asking this question should buy a battery yet.

Not because batteries are bad. Because the question itself reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how residential electrical systems work. Asking how big a battery bank needs to be to run a house is like asking how big a gas tank needs to be to drive a car. The answer depends on whether the car is a Prius or a Suburban, whether the trip is across town or across the country, and whether gas stations exist along the route.

Most people asking this question imagine their house as a fixed load. Twenty kilowatt hours a day, maybe thirty. Multiply by backup days, buy that many kilowatt hours of batteries, done.

This thinking produces disasters.

The Air Conditioner Will Destroy You

Central air conditioning is where battery backup dreams go to die. Not because of energy consumption, though that is bad enough. Because of what happens in the first half second after the compressor tries to start.

A 3 ton central AC unit runs at about 3,500 watts. Tolerable. The compressor motor starting from a dead stop is a different animal entirely. Locked rotor amperage on a typical residential compressor runs 60 to 90 amps at 240 volts. Do the math. That is 15,000 to 22,000 watts of instantaneous demand lasting 200 to 400 milliseconds.

Almost no residential inverter can deliver this.

The Tesla Powerwall 3 rates at 185 LRA. This number gets buried in spec sheets but it is the single most important specification in the entire residential battery market.

185 LRA means the Powerwall 3 can start almost any residential compressor without modification. The Enphase IQ Battery? Around 50 LRA. The FranklinWH? Similar. These units cannot start most central AC compressors even though their continuous power ratings look adequate on paper.

The industry does not advertise this because the industry would prefer to sell batteries first and deal with angry customers later.

Hard start kits exist. Thirty to eighty dollars, installs in twenty minutes on the compressor, reduces starting current by half or more. Every central AC system connected to battery backup should have one regardless of inverter size. The cost is trivial. The protection against nuisance faults is substantial. Yet most installers do not mention them and most homeowners do not know they exist.

But starting the compressor is only half the problem. Running it is the other half.

Central AC operating eight hours on a 95 degree day consumes 28 to 35 kWh. This single appliance can exceed total daily consumption for an otherwise efficient home. A battery bank sized for whole house backup including summer AC use needs to be three to four times larger than one sized for everything except AC.

The numbers get absurd fast. Forty kWh of battery capacity at current installed prices runs 35,000 to 50,000 dollars. For air conditioning backup.

Mini splits change everything and the residential battery industry should be screaming this from rooftops instead of quoting Powerwall prices. A 12,000 BTU mini split delivers equivalent cooling to a small window unit at 40 percent of the energy. Inverter driven compressors eliminate hard starting problems completely. Daily consumption drops from 25 to 35 kWh to 4 to 8 kWh. The surge that kills inverters disappears. A household replacing central air with two or three mini splits can suddenly achieve whole home backup with a battery bank one quarter the size.

This is not a minor optimization. This is the difference between a 15,000 dollar system and a 50,000 dollar system.

Electric Water Heaters Are a Scam for Battery Backup

Not actually a scam. Fine appliances. Terrible for battery backup.

A standard 50 gallon electric tank draws 4,500 watts when the elements are firing. The elements fire whenever water temperature drops below setpoint, which happens every time someone showers, runs the dishwasher, or does laundry. Total daily runtime runs 3 to 5 hours. Total daily consumption runs 13 to 22 kWh.

For one appliance.

That produces hot water.

Which a propane tankless unit produces using zero electricity except for a few watts of controls. Which a heat pump water heater produces using 4 to 6 kWh daily instead of 18. Which solar thermal panels produce using zero electricity and zero fuel.

Every dollar spent on battery capacity to back up an electric resistance water heater is a dollar that should have been spent replacing the water heater with something sane. The 8 to 15 kWh of daily consumption eliminated by switching to heat pump or propane translates to 10 to 20 kWh of battery capacity saved after accounting for depth of discharge and efficiency factors. That is 8,000 to 18,000 dollars of battery cost avoided. Heat pump water heaters cost 1,500 to 2,500 installed and qualify for federal tax credits.

The math is not close.

The Refrigerator Earns Its Place

Refrigeration is where battery backup makes unconditional sense.

Lose power for 48 hours in summer and a full refrigerator and freezer loses 300 to 600 dollars of food. The chest freezer in the garage with six months of bulk meat purchases can exceed 1,000 dollars in losses. This happens every hurricane season across the Gulf Coast and Florida. This happens every ice storm across the upper Midwest. This happens every time Pacific Gas and Electric decides fire risk requires shutting off power to half of Northern California.

A modern refrigerator draws 100 to 200 watts while running, cycles about 8 hours daily, and consumes 0.8 to 1.6 kWh per day. A chest freezer adds similar numbers. Both together total perhaps 3 kWh daily. Negligible. A 10 kWh battery can run refrigeration for three days without any solar input.

Older refrigerators with single speed compressors create more surge at startup, maybe 1,000 to 1,500 watts, but this falls well within the capability of any inverter sized for residential use. Modern units with variable speed compressors barely spike at all.

This load belongs on battery backup unconditionally. The consumption is tiny. The consequences of losing it are real money. The surge characteristics are benign. No other load in a typical house offers this ratio of benefit to cost.

Gas Furnaces Need Electricity and Nobody Remembers This

A 60,000 BTU natural gas furnace produces heat by burning natural gas. This requires zero electricity for combustion. This requires 400 to 800 watts of electricity for the blower motor that pushes heated air through ductwork into living spaces.

Without that 400 to 800 watts, a house with fifty thousand dollars of HVAC equipment sits cold during a winter power outage while the gas supply remains perfectly functional. This happens constantly during winter storms. The gas is there. The furnace is there. The electricity to run the blower is not.

Battery backup for a gas furnace blower is one of the highest value applications possible. The blower runs intermittently as the thermostat cycles. Maybe 4 to 10 kWh daily during cold weather depending on insulation quality and outdoor temperature. A modest battery bank keeps the entire heating system operational.

ECM blower motors found in furnaces manufactured after roughly 2015 draw half the power of older PSC motors for equivalent airflow. A house with an older furnace might benefit from blower motor replacement independent of any battery considerations.

Well Pumps Are Non Negotiable for Homes That Have Them

Municipal water keeps flowing during power outages. Well water stops.

A half horsepower submersible pump runs at 750 to 1,000 watts. Startup surge hits 2,200 to 2,800 watts. A one horsepower pump surges to 4,000 watts or more. Every time the pressure tank calls for water, the pump starts and that surge repeats. Twenty to fifty cycles daily in a typical household.

Inverters handle this if sized with adequate surge margin. Or a soft starter module costing 75 to 150 dollars eliminates the surge entirely by ramping voltage over two to three seconds. The pump starts gently. The inverter never sees the current spike. This small component prevents the need for significantly larger inverter capacity.

Daily energy consumption depends entirely on water usage. A conservation minded household draws 50 to 80 gallons daily, running the pump 15 to 25 minutes total, consuming under 0.5 kWh. A household with irrigation, multiple bathrooms in constant use, or livestock can run the pump 2 to 3 hours daily and consume 2 to 4 kWh.

The Calculation Everyone Gets Wrong

Daily consumption times days of autonomy. This is how most people calculate battery requirements. This is wrong.

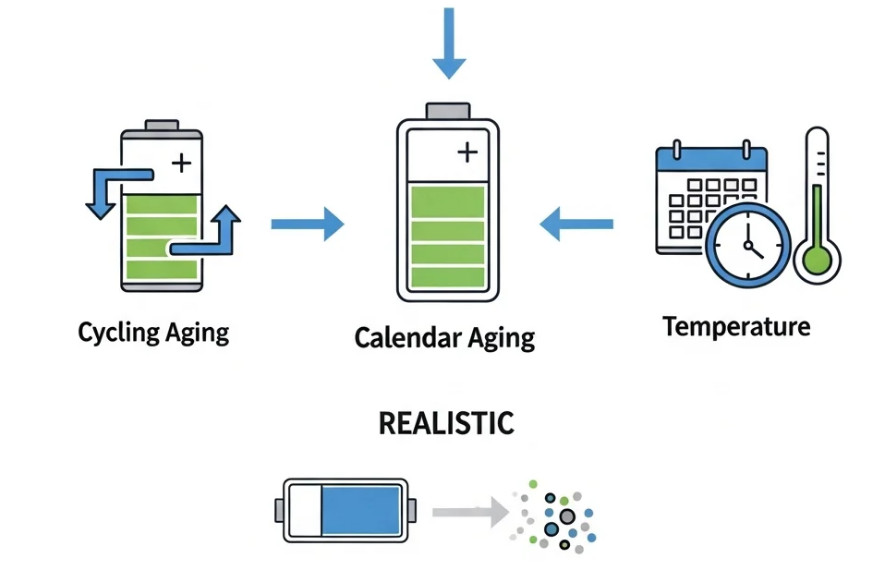

Batteries cannot discharge to zero without damage or severely shortened lifespan. Lithium iron phosphate cells tolerate deep discharge better than any alternative chemistry but still last dramatically longer when discharge is limited to 80 percent. The battery industry talks about this as depth of discharge. A 20 kWh battery at 80 percent depth of discharge provides 16 kWh usable capacity.

Then efficiency losses take another bite. Energy moving into and out of batteries loses something in both directions. The inverter converting DC storage to AC household power loses another percentage. Round trip from solar panel to battery to load might be 85 percent efficient in a good system. 90 percent in an excellent one. Never 100 percent.

Correct formula: daily consumption times days of autonomy, divided by depth of discharge, divided by efficiency.

A household consuming 12 kWh daily wanting 1.5 days of autonomy: 12 times 1.5 equals 18. Divided by 0.8 depth of discharge equals 22.5. Divided by 0.9 efficiency equals 25 kWh of rated battery capacity.

This 25 kWh provides 16 to 17 kWh of actually usable energy under real world conditions. Enough for 1.3 to 1.4 days at 12 kWh daily consumption. Close to the 1.5 day target. Accounting for conservative calculation rounding, adequate.

Skip the efficiency and depth of discharge adjustments and a household buying 18 kWh of batteries expecting 1.5 days of autonomy gets 1 day or less. Surprises during extended outages are unwelcome.

Solar Changes Everything About Autonomy Calculations

A battery bank without solar has one job: store enough energy to last until grid power returns. Three days of autonomy means storing three days of consumption.

A battery bank with solar has a different job: store enough energy to bridge overnight until solar production resumes the next morning.

Overnight bridging requires 12 to 16 hours of storage depending on season and latitude. Evening consumption from 6 PM to midnight might total 4 to 6 kWh for a typical household running refrigeration, lighting, network, and device charging. Overnight consumption from midnight to 6 AM adds another 2 to 3 kWh for refrigeration cycling and standby loads.

Six to nine kWh of overnight consumption. A 13.5 kWh Powerwall handles this comfortably with margin.

Then morning arrives. Solar production begins. The battery refills while simultaneously running daytime loads. By evening the battery is full again. The cycle repeats indefinitely as long as solar production exceeds consumption.

Extended heavy overcast breaks this pattern. Multiple consecutive days of 10 to 20 percent solar production drain the battery progressively until it empties or the weather clears. This is where the tension between overnight bridging and multi day autonomy creates difficult tradeoffs. A system sized for overnight bridging survives two maybe three cloudy days. A system sized for a week of clouds costs three to four times as much and spends most of its existence carrying unused capacity.

The Pacific Northwest and Great Lakes regions experience extended overcast stretching five to seven days during winter. The Desert Southwest rarely sees two consecutive cloudy days. Geography dictates what autonomy target makes sense.

For most grid tied applications in most climates, overnight bridging capacity plus one cloudy day margin lands at 15 to 25 kWh. This handles 95 percent of outage scenarios at a fraction of the cost of designing for the 5 percent that require either generator backup or accepting temporary discomfort.

Lithium Iron Phosphate Won and the Debate Is Over

Three chemistries appear in residential battery discussions.

Lithium iron phosphate delivers 3,000 to 6,000 cycles before capacity degrades to 80 percent of original. Cannot catch fire under any normal operating condition. Cell costs dropped below 60 dollars per kWh in 2024. This is the correct choice.

Nickel manganese cobalt offers higher energy density, meaning more storage in less space. Matters for electric vehicles where every pound affects range. Does not matter for batteries sitting in a garage. Cycle life runs 1,500 to 2,500. Multiple residential fires have involved NMC chemistry. Insurance companies increasingly penalize NMC installations. This is the wrong choice for new installations.

Lead acid costs less per nameplate kWh but can only discharge to 50 percent without rapid degradation. Double the rated capacity to get equivalent usable storage. Cycle life runs 500 to 1,200 depending on treatment. Round trip efficiency is 80 percent versus 95 percent for lithium, meaning 20 percent of stored energy disappears as waste heat. This chemistry made sense when it was the only option. It no longer is.

Temperature Matters More Than Spec Sheets Reveal

Lithium cells lose capacity in cold weather. At freezing expect 80 percent of rated capacity. At negative 10 Celsius expect 60 percent. At negative 20 expect 40 to 50 percent.

Worse: lithium cells cannot charge below freezing without permanent damage. Attempting to charge a frozen battery plates lithium metal onto the anode, destroying capacity that never recovers. Quality battery management systems prevent this by refusing charge commands when cells are too cold. The battery sits there unable to accept solar until it warms.

Cold climate installations require either indoor placement in conditioned space or batteries with internal heaters that consume power to warm cells before charging begins. This parasitic consumption must factor into winter energy budgets.

Heat accelerates aging. Every 10 degrees Celsius above 25 degrees costs roughly 20 percent of cycle life. A battery in a Phoenix garage hitting 45 degrees during summer months ages twice as fast as one in a climate controlled basement.

Battery placement matters. The difference between optimal and poor placement can be a factor of two in effective lifespan.

The Products Worth Considering

The Tesla Powerwall 3 at 13.5 kWh with 11.5 kW continuous output and 185 LRA motor starting capability is the product against which everything else should be measured. Not because Tesla is beloved. Because no competitor matches the combination of capacity, continuous output, and surge capability in a single integrated unit. Installed pricing runs 11,500 to 16,000 dollars depending on market and complexity. The 185 LRA number is why this product can start central AC systems that would fault lesser inverters.

The FranklinWH aPower 2 at 15 kWh with 10 kW continuous is the retrofit choice for homes with existing solar installations. AC coupling means it works with any inverter already present. Installed pricing runs 14,000 to 18,000.

The EG4 LifePower4 at 5.12 kWh per unit for 1,199 dollars is the value choice for anyone willing to handle their own installation or hire an electrician directly rather than going through a solar installer. Four units provide 20 kWh for under 5,000 dollars. Add an EG4 18kPV inverter for another 2,400. Total system cost under 8,000 versus 15,000 or more for the premium equivalents. The units are UL listed. The warranty is real. The catch is that installation requires electrical competence and permit navigation that stops most homeowners.

The Actual Answer

A house wanting backup for refrigeration, lighting, network equipment, device charging, and either a mini split or gas furnace blower consumes 8 to 14 kWh daily. A 15 kWh battery provides 24 to 40 hours of autonomy without solar input, indefinite autonomy with even modest solar. Cost runs 8,000 to 14,000 dollars installed through premium channels, 4,000 to 7,000 through DIY channels, after the 30 percent federal tax credit that expires December 31, 2025.

A house wanting the same loads plus well pump consumes 10 to 18 kWh daily. A 25 to 30 kWh battery bank handles this. Cost runs 18,000 to 28,000 installed.

A house wanting whole home backup including central air conditioning consumes 35 to 55 kWh daily in summer. A 50 to 70 kWh battery bank provides 24 hour autonomy. Cost runs 35,000 to 55,000 installed. At which point replacing central air with mini splits and cutting the battery requirement in half starts looking rational.

The battery bank needed to run a house depends almost entirely on which appliances get connected to that battery bank. The homeowners achieving practical backup at reasonable cost are the ones who redesigned their loads first and sized batteries second. Those trying to power unchanged consumption patterns with brute force battery capacity face costs that require either substantial wealth or irrational priorities to justify.