Yes. The technology exists and works fine.

That is the short answer, and for a lot of people asking this question, it is probably the only answer that matters. Hybrid inverters let batteries connect to grid-tied solar systems. The hardware is mature. Installation is routine. Nothing about it is experimental or cutting-edge at this point.

The longer answer involves money and tradeoffs that vary so much by location that general advice tends to be useless. But the basic technical question has a simple yes.

The Blackout Problem

Most people asking about batteries for grid-tied solar have already figured out, or recently discovered, that their solar panels do not work during blackouts. This comes as a shock if nobody explained it clearly before the system went in.

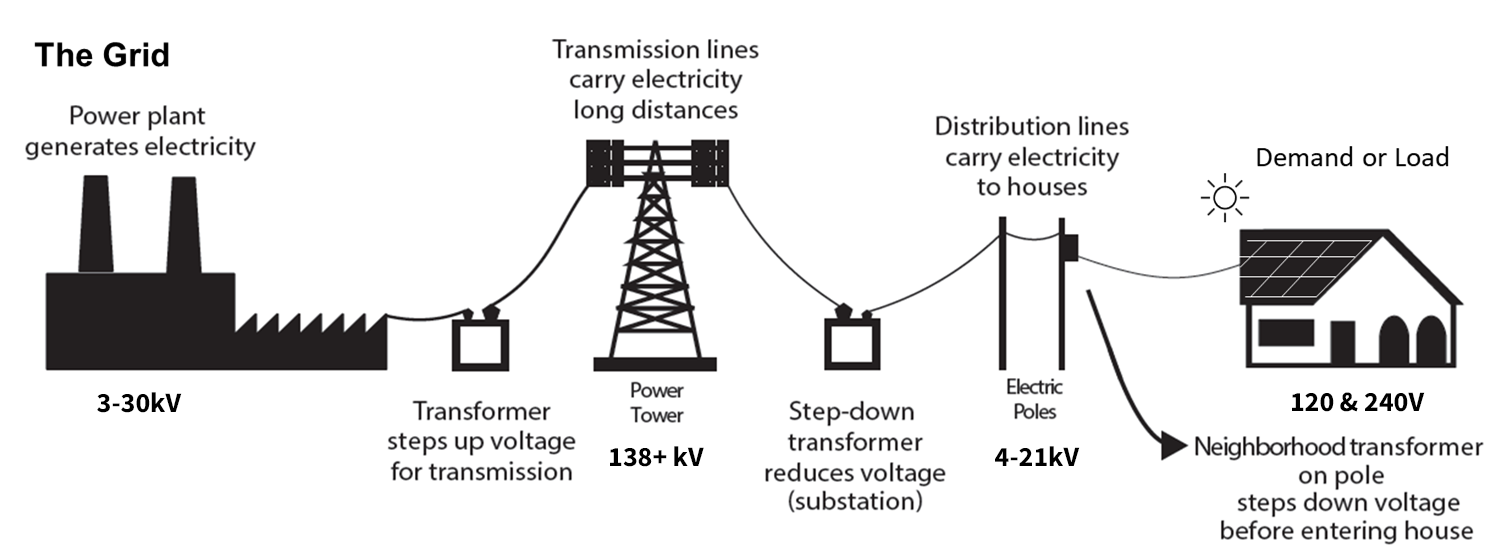

The inverter needs the grid to operate. When utility power drops, the inverter shuts off. Safety codes require this. A solar system pushing power into lines that utility workers think are dead could kill someone. So the inverter detects the outage and stops within a couple seconds.

The frustration is real. Sunny day, panels on the roof, no power in the house. Online forums have thousands of angry posts about this after every major outage. People feel cheated even though the installer probably mentioned it during the sales process. The detail did not stick until it mattered.

There is a particular kind of regret that shows up in these forum posts. Someone writes about watching their neighbor's gas generator running while their own silent solar array does nothing. The irony is not lost on them. They went solar partly for environmental reasons, and now they are wondering if they should have just bought a generator like everyone else.

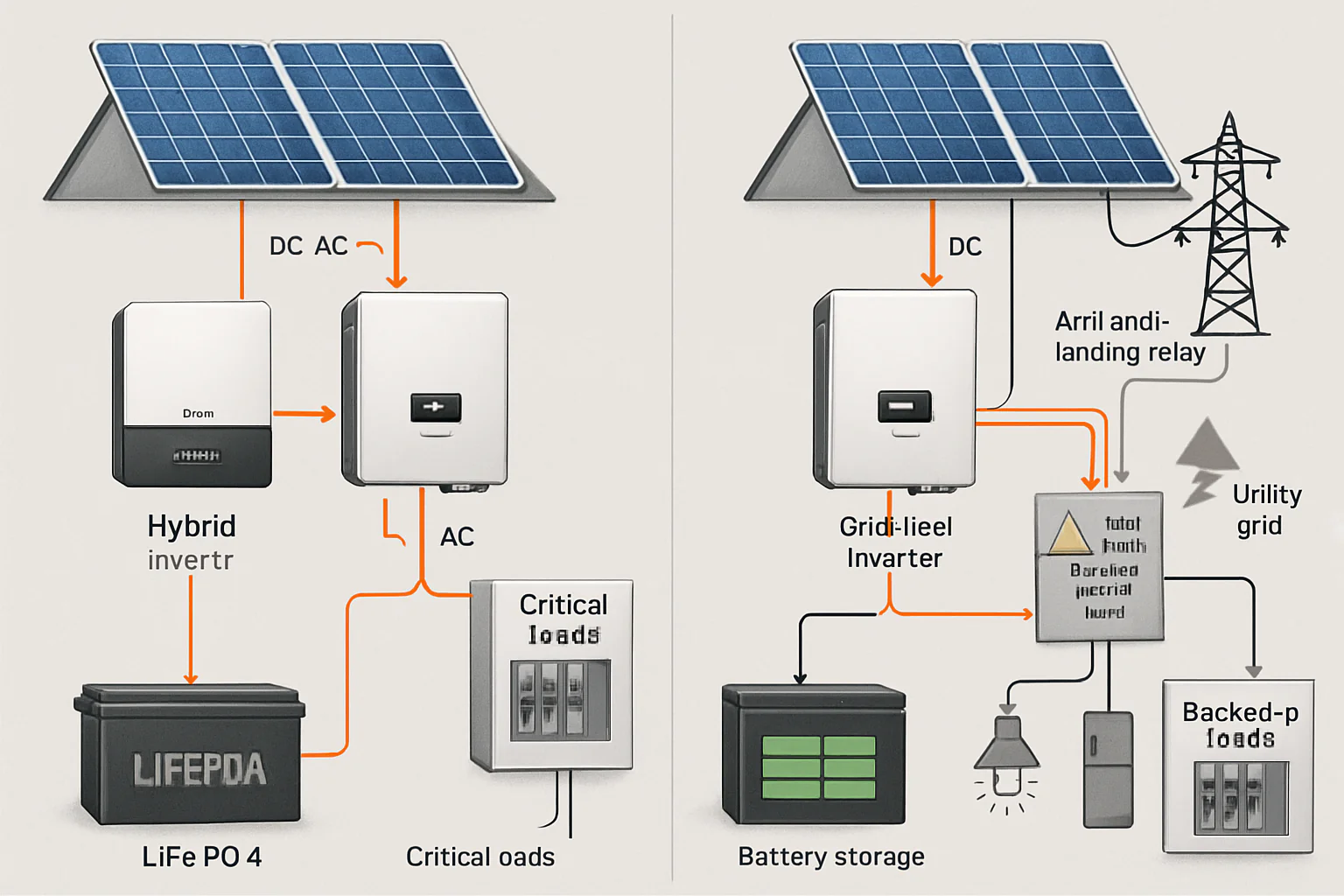

Adding batteries solves this. A hybrid inverter disconnects from the grid when power fails and keeps the house running from battery storage. Solar can continue charging the battery during the day. The system works independently until grid power returns.

The question of whether solving this is worth $12,000 to $18,000 depends on circumstances that vary wildly. Someone with a well pump in a rural area that loses power three or four times a year might find the investment obvious. Someone in a suburb with two brief outages in a decade might not. Someone who works from home and loses income during outages has different math than someone who just loses the contents of their freezer.

grid power system

California has added another variable. The PSPS shutoffs during fire season have turned "how often does the power go out" from a historical question into a political one. Utilities now cut power preemptively when fire risk is high. Areas that historically had decent reliability now face multi-day outages during dry, windy weather. The outages happen in October, often with clear sunny skies, exactly when solar panels would otherwise produce well.

Texas had its own version of this realization in February 2021. Puerto Rico has had it repeatedly since Maria. The assumption that grid reliability is a constant, something you can predict from past experience, has gotten shakier.

The Part That Actually Matters: Inverter Specs

Battery capacity gets all the marketing attention. Bigger numbers sell better. But the inverter specifications determine whether the system actually performs well in real situations.

Transfer time measures how fast the inverter switches from grid power to battery power when an outage hits. The number is in milliseconds. A 20ms transfer keeps computers running. A 150ms transfer crashes them and resets network equipment. Some cheap inverters take 200ms or more, which can damage sensitive electronics over repeated outages.

This spec rarely appears in the big bold text on product pages. It is buried in the technical specifications PDF that most buyers never read. The sales conversations focus on capacity and warranty length. Transfer time comes up only when someone specifically asks, or when something goes wrong after installation.

Peak power handling determines what the system can start. Motors draw several times their running power when they first turn on. An air conditioner that runs at 3,000 watts might spike to 7,000 watts for a few seconds during startup. An inverter rated for 5,000 watts continuous but only 5,500 watts peak cannot start that AC. It trips. The homeowner wonders why their expensive battery system cannot run the air conditioning during an outage.

The spec sheets use different terminology for this. Some say "peak power" or "surge rating." Others say "starting power" or list separate numbers for different time durations. A 10-second surge rating differs from a 3-second surge rating. Comparing across brands requires actually reading the documentation rather than glancing at summary tables.

Here is the thing about air conditioning specifically. In hot climates, backup power without AC often means backup power that nobody can actually use. A Florida homeowner in August might prefer a smaller battery that can start the air conditioner over a larger battery that cannot. The capacity advantage evaporates if the house becomes unlivable.

Well pumps have similar startup demands. Sump pumps somewhat less so. Refrigerators draw modest surge current by comparison. The mix of loads in a particular house determines whether peak power will be a problem.

Proper inverter selection is critical for reliable backup power performance

Communication protocols add a layer that almost nobody discusses at the consumer level. The inverter talks to the battery management system constantly during operation. Cell voltages, temperatures, charge state, fault conditions. This data flows through protocols. Some manufacturers use proprietary protocols that lock the battery to their own inverter. Others use open standards that allow mixing brands.

The proprietary lock-in matters more than it seems at first. Battery technology improves. Prices drop. The battery installed today will eventually need replacement. With open protocols, replacement means shopping the market for the best current option. With proprietary protocols, replacement means buying from the same manufacturer at whatever price they set, or replacing the entire system including inverter.

Systems going in today will need battery replacement in 12 to 18 years. The 2037 battery market will look different from the 2025 market. Flexibility to choose then has value now.

These specs matter more than battery size for most real-world use. A 10 kWh battery with a good inverter beats a 15 kWh battery with a slow, weak inverter almost every time. Nobody talks about this in the marketing materials. The spec sheets list the numbers, but buyers compare capacity and price. The inverter quality difference shows up later.

LFP Won

Four years ago there was a real choice between lithium iron phosphate and nickel manganese cobalt batteries. NMC had higher energy density. Smaller boxes. Lighter weight. For a while the tradeoffs seemed reasonable enough that different manufacturers went different directions.

Then LFP manufacturing scaled up, mostly in China, and prices dropped faster than NMC prices. By 2023 the cost was about the same. By 2024 LFP was often cheaper. Meanwhile the cycle life difference stayed constant: LFP lasts 6,000 to 10,000 cycles, NMC lasts 2,000 to 3,000. Same price, twice the lifespan. The calculation became simple.

Tesla switched Powerwall to LFP. Everyone else followed. The residential market consolidated around a single chemistry faster than most industry observers expected.

Anyone shopping for home storage should insist on LFP. This is not a close call anymore. It has not been a close call for about two years now, even though the marketing materials from some manufacturers still pitch NMC as if the tradeoffs were still competitive.

NMC still makes sense for electric cars where every pound of battery weight reduces driving range. The density advantage matters there. For a battery sitting in a garage, nobody cares if it weighs 250 pounds instead of 200 pounds. The floor holds either one just fine.

There are still NMC residential batteries on the market. Some of them are older inventory. Some are from manufacturers slow to retool their production lines. None of them make sense to buy at this point. The cycle life gap is too large.

Economics

This is where general advice breaks down completely.

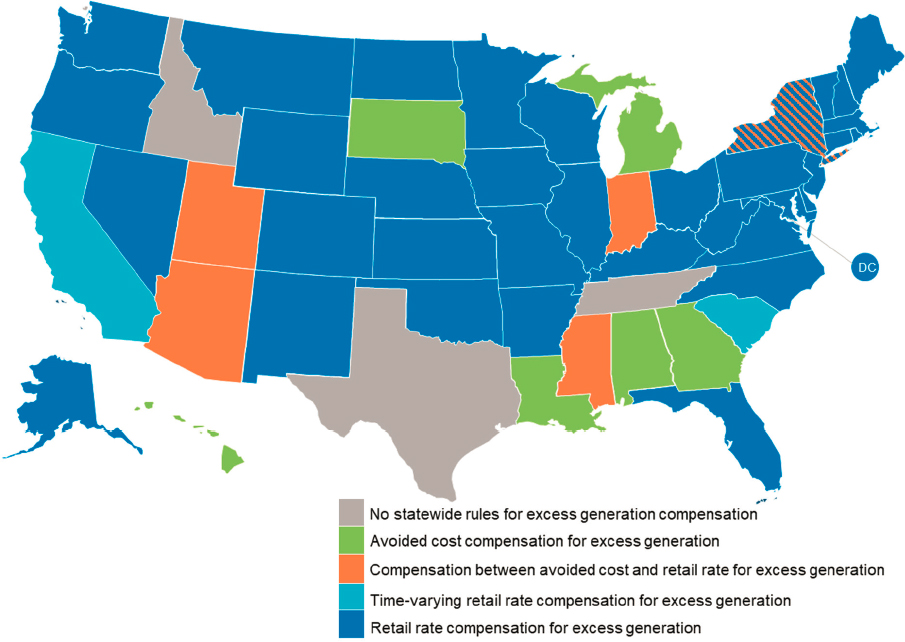

In California under NEM 3.0, batteries make obvious financial sense. Export rates dropped to around $0.05/kWh. Peak import rates run $0.35 to $0.50/kWh depending on utility and rate schedule. The spread between those numbers is money. Store solar during the day instead of exporting it. Use the stored power during expensive evening hours. A 13 kWh battery cycling daily captures over $1,500 per year just from this difference. Add time-of-use arbitrage on top and the numbers get better.

The California situation changed fast. Before April 2023, NEM 2.0 credited exports at roughly retail rates. The grid acted like free storage. Batteries added cost without adding much value beyond backup. Then NEM 3.0 hit and the economics flipped. Projects that would have made no sense in 2022 became obviously profitable in 2023.

Net metering policies vary dramatically by state and can change rapidly

In states with full retail net metering and flat rates around $0.12/kWh, batteries make almost no financial sense. Export solar to the grid at $0.12, import it back later at $0.12, the round trip costs nothing except the 5-10% losses in the battery itself. There is no spread to capture. A battery just sits there providing backup for rare outages. At $15,000 installed, the investment does not pay back on financial terms unless backup power has very high personal value or the net metering policy is about to change.

The difference between these two scenarios is not subtle. California payback might be 7 years. Midwest flat-rate payback might be never. Same technology, same installation process, completely different financial outcomes.

Between the extremes the picture gets murky. Time-of-use rates create spreads even without solar. Demand charges on some residential plans reward peak shaving. State incentives knock thousands off installed costs in Massachusetts, Vermont, Oregon, a few others. Virtual power plant programs pay for grid services in an increasing number of utility territories.

The inputs to any economic calculation vary by utility, by rate schedule, sometimes by the specific date an interconnection agreement was signed. Grandfather clauses matter. Rate changes matter. Incentive availability matters. Someone trying to figure out whether batteries make sense needs numbers specific to their situation, not general claims.

One pattern worth noting: policy tends to move in the direction of worse net metering over time. Utilities do not like distributed solar for reasons that have to do with their revenue model and cost allocation between customer classes. The political fights play out slowly, but the direction has been fairly consistent. States that have full retail net metering today may not have it in five years.

California homeowners who added batteries before NEM 3.0 looked like they were overpaying at the time. Now their investment looks smart. Whether this pattern repeats elsewhere is a guess, not a certainty. But the possibility that net metering gets worse is worth considering when evaluating the economics of a system expected to last 15 to 20 years.

Sizing

The biggest battery is not always the best battery for a particular situation.

Capacity that sits unused costs money without returning value. A 25 kWh battery in a house that only cycles 12 kWh daily wastes the investment in the other 13 kWh. That money would have been better spent on a nicer inverter, or not spent at all.

For backup purposes, the calculation starts with what needs to run during an outage. Refrigerator, lights, internet, phone charging. Maybe a sump pump. These loads run 300 to 600 watts average, which works out to 7 to 15 kWh per day. A 10 kWh battery covers the essentials for a day or so.

Air conditioning changes everything. Central AC draws 2,000 to 4,000 watts while running. Even cycling on and off, it can double or triple daily consumption during hot weather. Someone in Arizona or Florida who wants to run AC during outages needs a much larger battery than someone in Minnesota who just wants to keep the furnace fan running.

For self-consumption and rate arbitrage, the calculation is about matching battery capacity to the kWh actually used during expensive hours or after solar production ends. If evening consumption runs 18 kWh, a 20 kWh battery captures almost all of it. A 30 kWh battery in that same house has 10 kWh that never gets used.

Oversizing feels safe. Bigger seems better. But the extra capacity does not provide extra value if it never cycles.

DC Coupling vs AC Coupling

DC coupling works better for new installations. AC coupling works better for adding batteries to existing solar with microinverters.

The efficiency difference is real but not dramatic. The installer will know which applies. This is not the decision that makes or breaks the project.

The Bottom Line

Batteries work in grid-tied solar systems. The technology is settled. The installation process is routine.

Whether batteries make sense depends almost entirely on local factors: utility rates, net metering rules, grid reliability, available incentives. In some markets the economics are obviously positive. In others they are obviously negative. In many they are ambiguous enough that personal preferences about backup power and energy independence end up driving the decision more than financial calculations.

The answer to the technical question is yes. The answer to whether it is worth it requires more information than a general article can provide.