No.

That's the answer for most people reading this, and the solar industry's refusal to say it plainly is why so many buyers end up with expensive equipment they didn't need.

The longer answer requires understanding one number that determines almost everything, and that number has nothing to do with batteries themselves.

Net Metering Is the Whole Game

Your utility has a policy that dictates what they pay you when your solar panels send electricity to the grid. Look it up before doing anything else. That policy, more than battery technology or brand or capacity, determines whether storage makes any financial sense for your house.

In states with full retail net metering, the grid functions as a free battery. Export power at noon, get credited at the full retail rate. Import power at dinner, spend those credits. The accounting zeros out. A physical battery in this scenario does the same thing the grid already does for free, except worse because batteries lose about 10% to inefficiency and they cost ten grand.

California changed this equation in April 2023.

Their new policy, NEM 3.0, pays solar owners around eight cents per exported kilowatt-hour while charging forty cents or more for imports. That spread didn't exist before. Now it does, and suddenly storing your own power instead of selling it cheap and buying it back expensive makes obvious sense.

The battery industry barely existed in residential form until net metering started dying. That's not coincidence. The product only works economically when policy creates an artificial gap between export and import prices. When that gap doesn't exist, batteries are decorations that make people feel good about energy independence while quietly bleeding money.

Before researching battery brands, before getting quotes, before reading another word of this article, find out what your utility pays for exported solar.

Before researching battery brands, before getting quotes, before reading another word of this article, find out what your utility pays for exported solar. If it's more than sixty percent of the retail rate, stop researching. A battery will not pay for itself in your lifetime, and anyone telling you otherwise is selling something.

The solar industry hates this framing. It makes their battery business depend on regulatory failure rather than product merit. But the numbers don't lie. In regions with good net metering, battery attach rates stay under 20%. In California post-NEM 3.0, attach rates exceed 60%. The product didn't improve. Customers didn't get smarter. The policy changed, and suddenly a purchase that made no sense became almost mandatory.

This dependency on policy creates a strange dynamic for anyone buying solar today in a state that still has decent net metering. The battery doesn't make sense now. It might make sense in three years if policy deteriorates. Installing solar with battery-ready wiring costs maybe a thousand dollars extra and preserves the option. Installing without it means expensive retrofitting later if circumstances change.

The utility industry has lobbied against net metering for over a decade, arguing that solar owners shift grid maintenance costs onto non-solar ratepayers. Whether this argument holds merit matters less than its political effectiveness. Nevada gutted its net metering in 2015, triggering a collapse in solar installations, then partially restored it in 2017 after public backlash. Hawaii moved to self-supply policies. Arizona reduced export compensation to around 75% of retail rates.

Each state's trajectory differs in timing and severity, but the direction is consistent. Full retail net metering is disappearing across high-solar-penetration states. The question for buyers isn't whether their local policy will change, but when.

The Backup Power Problem

Battery companies lead their marketing with backup power because it bypasses economic analysis entirely. Fear sells. Rational calculation doesn't.

What does a standard battery actually deliver during an outage?

A standard home battery holds around 13 kilowatt-hours. After accounting for the portion that can't be discharged without damage, maybe 10 kilowatt-hours are actually usable. The average American home consumes 30 kilowatt-hours daily.

Without solar recharging, the battery lasts eight hours if you're careful about what you run. Three hours if you try to live normally. Want air conditioning during a summer blackout? Two hours, maybe less.

The mental image that battery marketing encourages, the house humming along normally while neighbors sit in darkness, requires three or four times the storage capacity that standard systems provide. That costs forty thousand dollars. At that price a propane generator makes more sense, and generators don't care about clouds.

Someone on a CPAP machine has different backup needs than someone worried about frozen food. A household in PG&E territory subject to multi-day Public Safety Power Shutoffs faces different risks than a household in a city with two outages per decade.

The honest framing: a standard battery provides limited backup for critical loads during short outages. If that matches your actual risk profile, the feature has value. If your concern is multi-day grid failures or whole-house operation, the standard product doesn't solve it.

VPP Programs

Virtual Power Plant programs aggregate home batteries and dispatch them during grid emergencies in exchange for payment. Tesla paid Powerwall owners around ten million dollars through these programs in 2024.

Massachusetts pays over a thousand dollars per year just for enrollment. California pays a couple hundred. Some states pay nothing because no program exists.

That variance matters more than people realize. A thousand dollars annually from VPP alone, stacked on whatever the battery saves through rate arbitrage, pushes payback toward five or six years. That's a good investment. A couple hundred annually barely moves the needle. Zero is zero.

About half of states have VPP programs. Compensation varies wildly. Check whether yours does, and what it pays, before getting excited about battery economics you read in a national article written by someone in Massachusetts.

Degradation

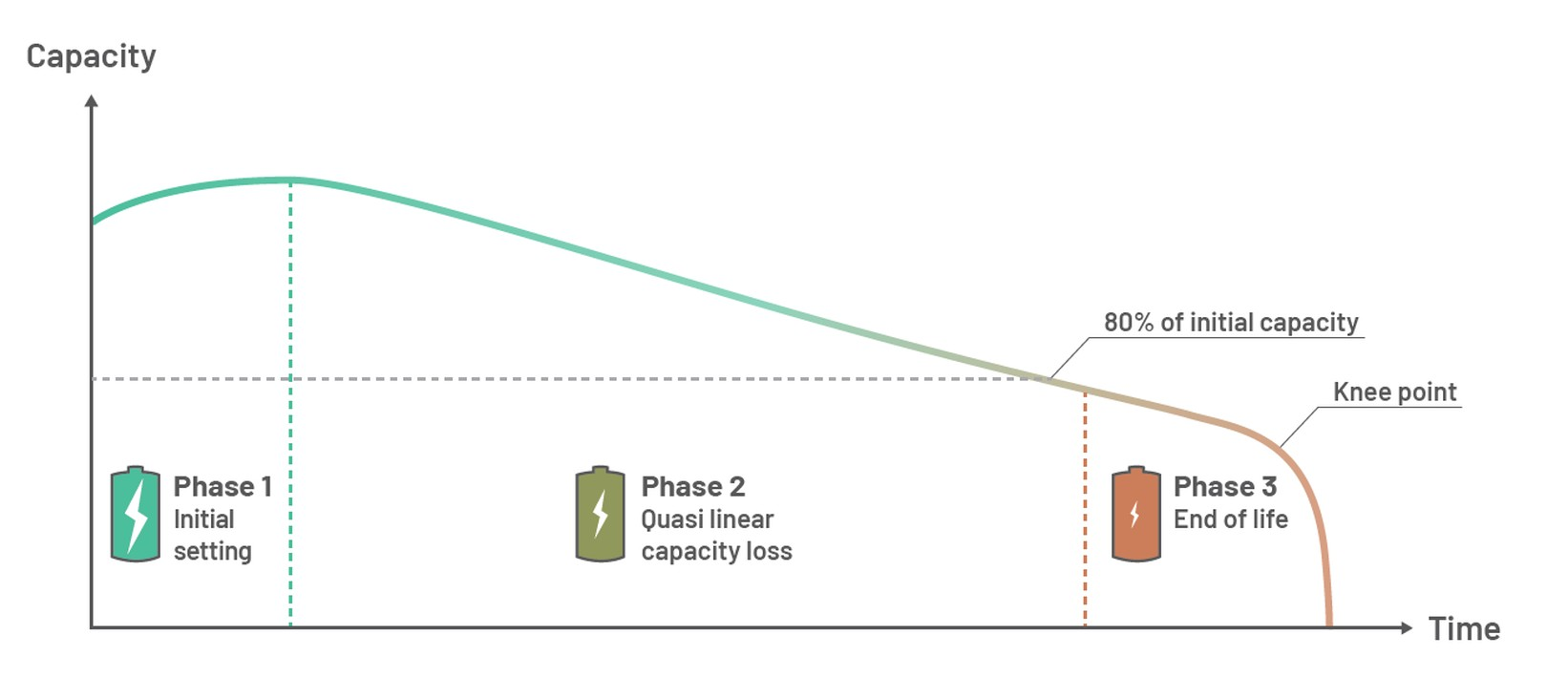

Battery capacity drops every year. Manufacturers warranty 70% retention after ten years.

That sounds fine until someone actually models what it means financially. A battery saving a thousand dollars in year one saves maybe 900 in year five and 750 in year ten as capacity declines. Payback projections that assume constant savings are wrong. They're used anyway because they make the numbers look better.

Temperature accelerates the problem. A battery in a Phoenix garage ages roughly 40% faster than one in a Seattle basement. Installation location matters more than most buyers realize and more than most installers discuss.

The ten-year warranty has become a psychological anchor implying ten-year useful life. Some batteries fail at year seven. Others limp to year fifteen at 65% capacity. The warranty covers catastrophic failure, not the gradual decline that actually erodes value.

Why Installers Push Batteries

A solar-only installation has thin margins. Competition drove pricing down over the past decade. Many installers struggle to profit on panels alone.

Batteries carry higher margins. A $10,000 battery sale might contribute $2,000 or more to installer profit. A $15,000 panel installation might contribute $1,500.

Customers asking whether they need a battery are asking someone with a financial interest in the answer.

This creates an obvious incentive to recommend batteries to everyone regardless of fit. The installer who tells a customer in a full-net-metering state that they don't need a battery makes less money than the installer who talks them into one anyway. Customers asking whether they need a battery are asking someone with a financial interest in the answer.

None of this means installers are dishonest. Most believe batteries are good products. They are, in the right circumstances. But the right circumstances exclude most American households, and the sales conversation rarely acknowledges this.

So Should You Buy One?

Probably not.

If your utility offers full retail net metering, the grid is already doing what a battery does, for free. If your electricity rate is flat throughout the day, no arbitrage opportunity exists. If you consume under 8,000 kilowatt-hours annually, the savings base is too small. If you have credit card debt, pay that first.

The people who should buy have a specific situation: net metering compensation under 30% of retail, time-of-use rate spreads over 25 cents per kilowatt-hour, an active VPP program in their territory, and consumption over 8,000 kilowatt-hours annually. With all four, payback lands around five to seven years. With two or three, the decision is genuinely uncertain and non-economic factors reasonably matter.

The federal 30% tax credit expires at the end of 2025. Anyone who has concluded a battery makes sense should probably act before then.

Two numbers determine everything: net metering export compensation and time-of-use rate spread. Look those up before talking to anyone who profits from your decision.