A warehouse storing lithium batteries caught fire in New Jersey a couple years back. The responders used ABC extinguishers. The fire spread. This happens more often than industry publications report, partly because the incidents that don't result in major property loss or injury tend not to generate documentation, and partly because facilities have legal and insurance reasons to keep quiet about near-misses.

The basic problem is understood by people who research battery fires, and has been understood for at least fifteen years, but the understanding hasn't propagated into standard practice at most facilities storing lithium batteries. What researchers know and what warehouse managers do remain disconnected.

The Chemistry

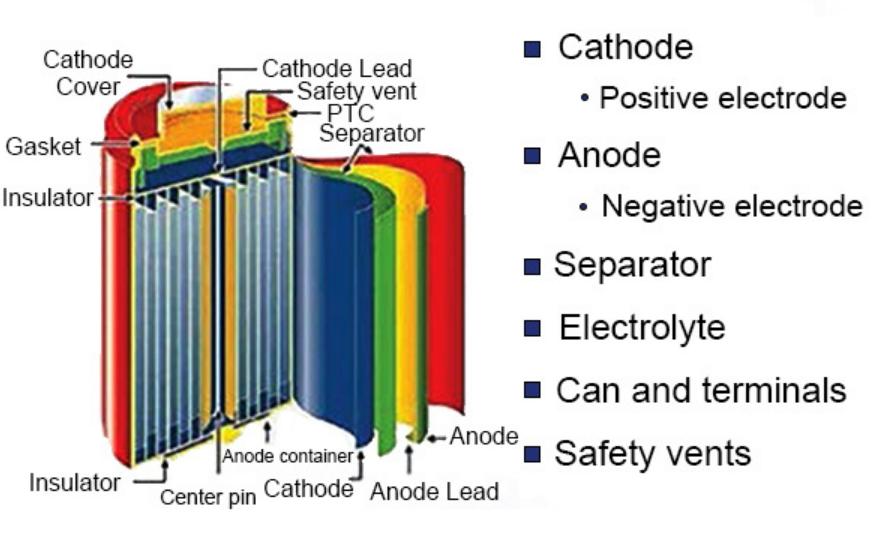

Thermal runaway in lithium cells is not fire. The distinction matters for suppression strategy.

Conventional fire requires atmospheric oxygen. Remove the oxygen and combustion stops. This principle underlies essentially all fire suppression technology: water absorbs heat, CO2 displaces oxygen, dry chemical interrupts chain reactions that require oxygen to proceed. The principle holds for burning wood, burning gasoline, burning wire insulation.

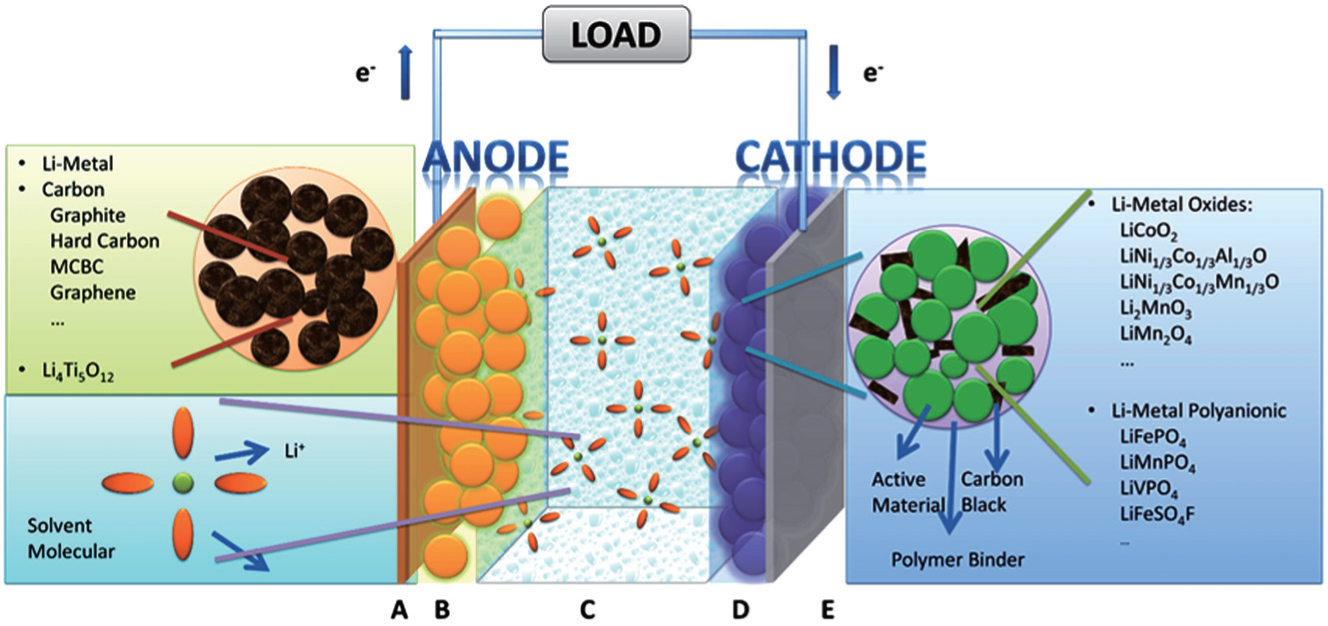

The internal structure of lithium-ion cells contains oxygen atoms bound in the cathode's crystal structure

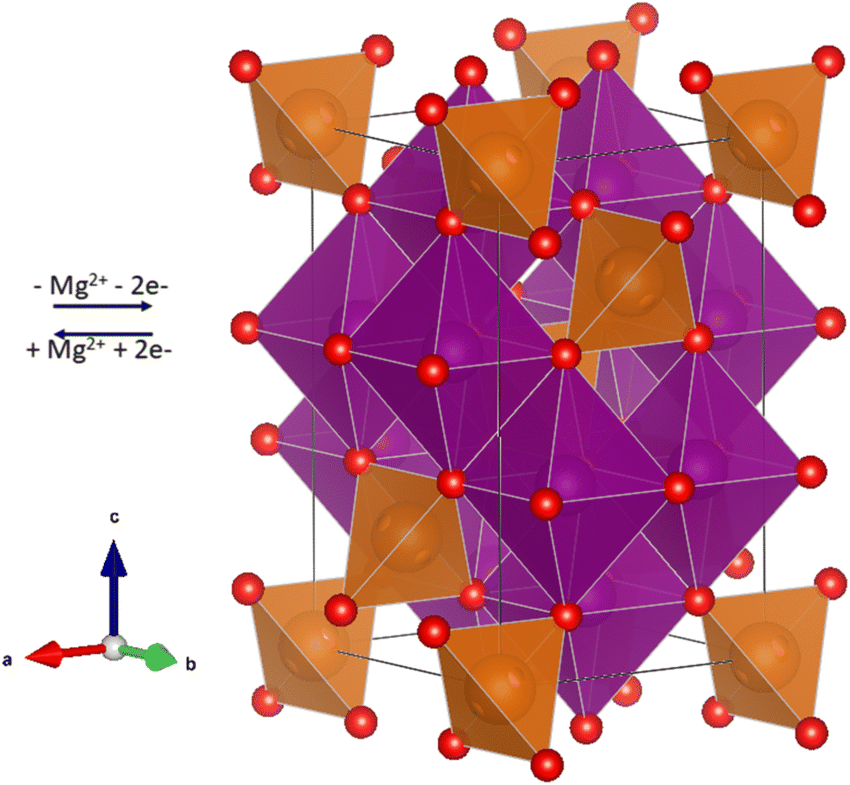

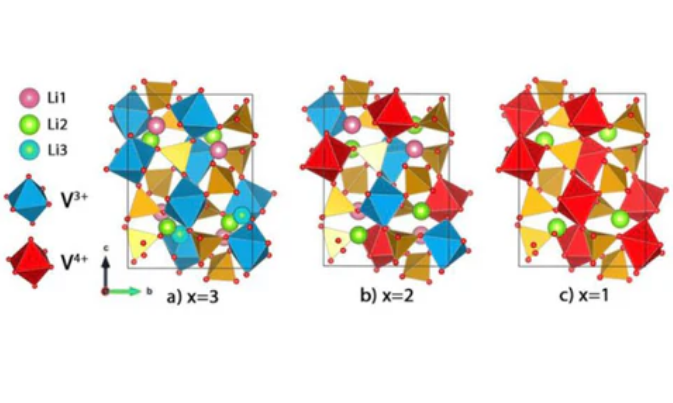

Lithium battery thermal runaway generates its own oxygen. The cathode material in lithium-ion cells contains oxygen atoms bound in its crystal structure. When the cell gets hot enough, the cathode releases that oxygen. The reactions that follow don't need air. They proceed inside a sealed cell with no atmospheric access whatsoever.

The temperature threshold for cathode oxygen release varies by chemistry. Lithium cobalt oxide cells behave differently from lithium iron phosphate cells. State of charge matters. Cell age matters. Mechanical damage history matters. Published research gives ranges rather than precise thresholds because the variation is real. Something like 180-250°C captures most scenarios, but edge cases exist outside that range.

Once oxygen release begins, temperatures climb fast. Peak temperatures somewhere in the 800-1000°C range are typical for cylindrical cells, though measurements vary depending on how and where temperature is recorded during what is, after all, a violent and rapid process. These temperatures exceed the melting point of aluminum. The cell casing fails. Contents vent.

The energy involved is modest per cell but adds up. A single 18650 cell stores maybe 40-50 kJ depending on chemistry and charge state. That's roughly equivalent to a large firecracker. But cells don't fail in isolation. Heat from one failing cell raises the temperature of its neighbors. Those neighbors fail. More heat. More neighbors. A hundred cells cascading releases energy that can't be dismissed as trivial.

Why Conventional Suppression Fails

The New Jersey incident and others like it follow a pattern. Workers see fire. Workers use available extinguishers. Fire spreads.

ABC dry chemical is monoammonium phosphate. The suppression mechanism assumes atmospheric oxygen is feeding the fire. Against a fire that generates its own oxygen internally, the mechanism accomplishes nothing useful. There's some evidence that powder coating on cell surfaces can actually impede heat dissipation and make things worse, though the research on this is thinner than it should be.

Water-based suppression fails differently. Water hitting a surface at several hundred degrees Celsius vaporizes instantly. The steam expansion in an enclosed space creates pressure waves that can rupture adjacent cell casings. More cells vent. More cells enter thermal runaway. Whether this is better or worse than dry chemical probably depends on the specific geometry of the installation, but neither is good.

Clean agent systems like FM-200 work by displacing atmospheric oxygen. Against thermal runaway that doesn't need atmospheric oxygen, FM-200 accomplishes nothing except making the air unbreathable for anyone still in the space.

The fundamental problem is that fire suppression technology evolved over decades to address combustion. Thermal runaway isn't combustion. Applying combustion-suppression strategies to thermal runaway produces results ranging from ineffective to counterproductive.

Vermiculite

The suppression approach that works against lithium battery thermal events uses vermiculite, a mineral that's been in construction insulation for a century.

Vermiculite is thermally stable above 1000°C. When dispersed in water and sprayed on failing cells, it deposits a mineral coating as the water evaporates. That coating acts as a thermal barrier. Heat transfer from burning cells to adjacent cells drops significantly. The cascade slows or stops.

How significantly? Published figures vary. Lab tests under controlled conditions show large reductions in inter-cell heat transfer. Field conditions introduce variables that lab tests don't capture. The general conclusion that AVD works better than alternatives seems solid. The specific magnitude of improvement probably depends on details of the application.

AVD also provides evaporative cooling from the water component and some containment of off-gassing from the coating. These secondary effects matter but the propagation interruption is the primary mechanism.

The puzzling thing is how long AVD took to reach commercial markets. Vermiculite's thermal properties have been known for decades. Lithium battery thermal runaway has been studied since at least the 2000s. The chemistry isn't exotic. The formulation challenges aren't insurmountable. Yet AVD extinguishers didn't appear commercially until the mid-2010s.

The lag probably reflects fire equipment industry economics more than technical barriers. Established product categories have established customers and predictable margins. New categories require investment with uncertain returns. The regulatory framework for extinguisher certification didn't have a lithium battery category, which created additional barriers for manufacturers wanting to bring AVD products to market. By the time commercial AVD products became available, lithium batteries had already become ubiquitous in applications from laptops to grid storage.

Regulatory Gaps

NFPA 855 established requirements for lithium battery installations in its 2020 edition. Before that, lithium battery storage got treated as generic electrical equipment.

The 2020 standard mandates lithium-specific suppression above 20 kWh. This threshold was presumably meant to capture commercial installations while exempting small-scale consumer applications. In practice, it created obvious workarounds. Size your battery units at 19 kWh each and the threshold never triggers, regardless of how many units you install.

Battery storage facilities often struggle to balance safety requirements with operational costs

Adoption varies by state. Some states adopted quickly. Some haven't adopted at all as of late 2024. Among states that adopted, enforcement ranges from rigorous to essentially nonexistent. Facilities built before enforcement began remain largely unmodified.

The three-foot spacing requirement between battery arrays has a clear physical rationale: reducing radiant heat transfer below propagation threshold. Walk through actual battery storage facilities and the requirement is frequently violated. Space costs money. The fire risk is probabilistic. The rent is certain.

Ventilation requirements exist but the specified flow rates are adequate for normal operation, not for thermal events. A battery installation experiencing cascading thermal runaway generates toxic gases faster than any building ventilation system can clear them. Whether facility operators understand this limitation is unclear.

The HF Problem

The toxic hazard that gets least attention is hydrogen fluoride.

Standard lithium-ion electrolyte contains fluorine compounds. During thermal runaway, decomposition releases HF gas. Concentrations in enclosed spaces during active events can reach levels far exceeding what's considered immediately dangerous.

HF toxicity works through calcium binding. The fluoride ion penetrates cell membranes and binds calcium irreversibly. Systemic calcium depletion affects cardiac function. The dangerous part: symptoms are delayed. Exposure that causes no immediate distress can produce pulmonary edema and cardiac effects hours or days later.

Standard evacuation PPE doesn't protect against HF. Adequate protection requires supplied-air respirators. How many battery storage facility workers have access to supplied-air respirators and training to use them? Probably not many.

The HF hazard should probably get more attention in facility planning than it typically does. Emergency plans for battery storage facilities tend to treat the hazard as smoke and combustion gases, which misses the specific characteristics of HF exposure.

Vehicle Batteries

Electric vehicle battery fires present different challenges than stationary storage.

Pack architecture determines propagation characteristics. Cells within EV battery modules are closely packed with minimal thermal barriers. Progression from single-cell failure to full pack involvement can happen fast, though the exact timeframe depends on pack design, state of charge, and other variables. Different EV manufacturers use different pack architectures with different propagation characteristics.

Standard fire apparatus foam is water-based and produces the same problems as direct water application. Specialized equipment exists for EV battery fires, including systems that penetrate pack enclosures to deliver suppressant directly to cells. This equipment is expensive. Most fire departments don't have it. The departments that do tend to be well-funded urban departments. Rural departments responding to highway incidents typically have only conventional equipment.

Whether this capability gap will close as EV adoption increases is uncertain. The equipment costs tens of thousands of dollars per unit. The specialized suppressants cost substantially more per gallon than standard foam. Budget allocation for equipment addressing a small fraction of current incident volume is hard to justify, but the fraction is growing.

Insurance

FM Global adjusted property insurance data sheets in late 2023, implementing significant premium increases for facilities storing lithium batteries without approved suppression systems. The magnitude varies but the direction is clear: insurers have decided the risk warrants higher pricing.

Insurance requirements are increasingly shaping facility safety investments

FM approval is more specific than marketing claims. Products meeting FM testing requirements have demonstrated efficacy under controlled conditions. Products claiming lithium battery effectiveness without FM approval may or may not work as claimed. The certification gap creates situations where facility operators believe they have adequate protection based on marketing materials, but coverage disputes arise after incidents because the installed equipment didn't meet policy requirements.

Disposal

Suppression events generate contaminated waste. Used AVD material mixed with battery residue picks up lithium compounds, electrolyte decomposition products, and heavy metals from cell components. Under RCRA, this material typically qualifies as hazardous waste requiring manifested transport to licensed disposal facilities.

Disposal costs add up. A moderate-scale incident can generate a thousand pounds or more of contaminated material. At several dollars per pound for hazardous waste disposal, the post-incident costs reach five figures before any structural repair.

Most facility emergency plans don't address disposal. The focus is suppression and evacuation. Cleanup logistics come as an unpleasant discovery after the fact.

When Specialized Equipment Matters

The threshold question for lithium-specific suppression is roughly 5 kWh total capacity or dense cell packing regardless of capacity. Below that, standard suppression is probably adequate. Single-cell events in consumer electronics don't have enough thermal mass to sustain cascading propagation.

Above that threshold, or in configurations where cells are packed closely enough that heat transfer between cells is fast, lithium-specific suppression becomes important. The cost difference between standard and AVD extinguishers is a few hundred dollars. Against any meaningful probability of thermal event in a facility storing significant battery capacity, the investment math favors appropriate equipment.

The Trajectory

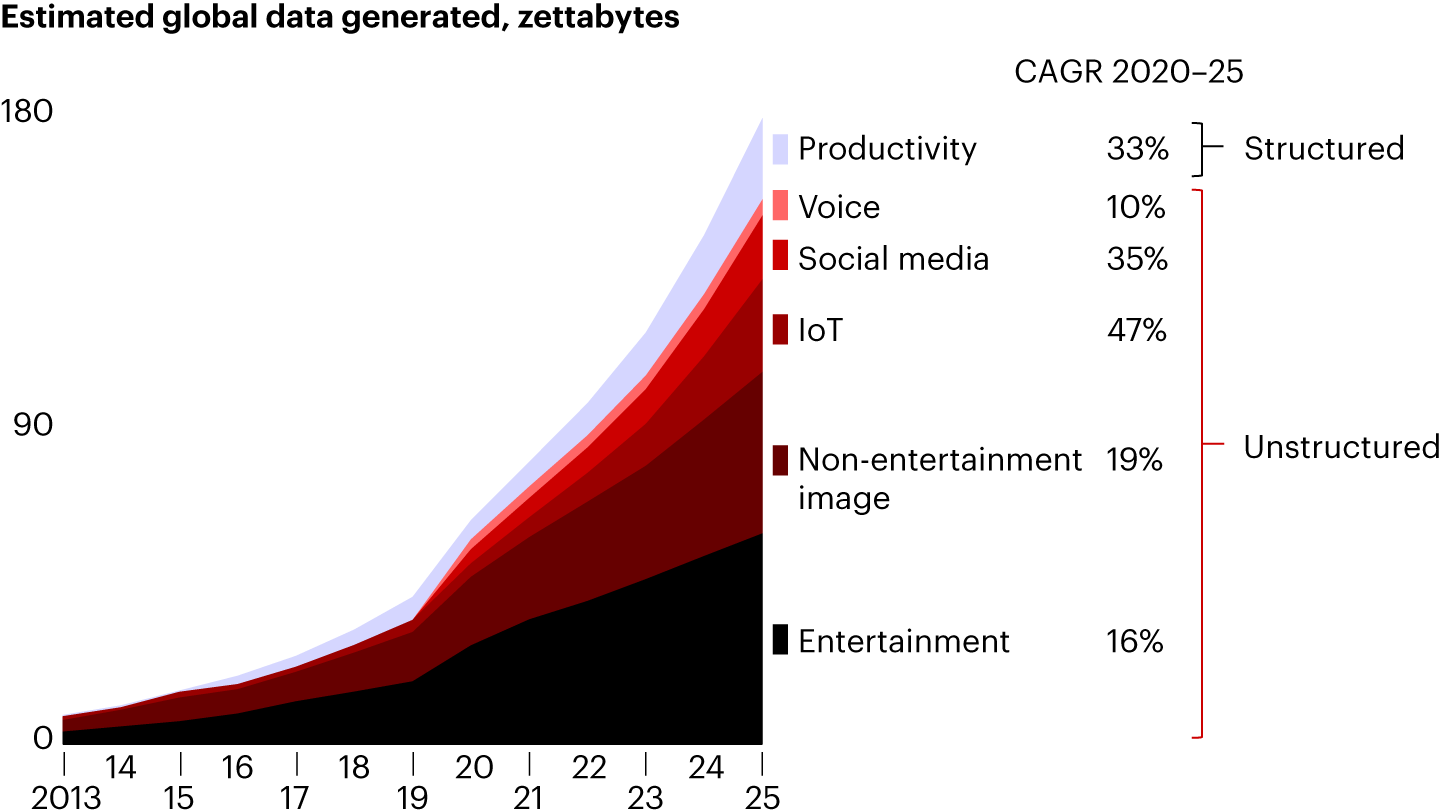

Lithium battery deployment continues accelerating. Grid storage, EVs, consumer electronics, residential storage. The installed base grows every year.

Fire protection practices lag. AVD equipment remains a specialty item. Vehicle suppression capability concentrates in departments that can afford it. Codes evolve slowly and enforce unevenly.

The gap will close eventually. Codes strengthen after incidents. Insurance requirements tighten after claims. Training expands after response failures. This reactive pattern is consistent across fire protection history. It's playing out again with lithium batteries.

How much damage accumulates during the transition depends on how quickly practices catch up to hazards. The New Jersey warehouse was one incident. The conditions that produced it, repeated across thousands of facilities storing lithium batteries with suppression equipment designed for different fire types, haven't fundamentally changed. Some facilities will make the transition to appropriate protection proactively. Others will make it after something goes wrong. The choice, for now, belongs to individual facility operators working with incomplete information and competing budget priorities.