Recycling facilities across North America are burning at unprecedented rates. In 2024, waste management sites reported 430 fires, a 15% surge from the previous year and the highest figure since systematic tracking began, according to data compiled by the Environmental Research & Education Foundation. The National Waste & Recycling Association estimates over 5,000 facility fires occur annually, with lithium-ion batteries identified as the dominant ignition source.

These fires are not accidents. The chemistry is understood. The failure modes are documented. The collection infrastructure that would prevent them could be built.

It has not been built.

The companies selling lithium battery devices have found it cheaper to externalize disposal costs onto municipalities, waste workers, and the environment. At point of sale, consumers receive no meaningful education about the hazardous materials they are purchasing. Packaging bears recycling symbols that imply curbside recyclability while actually indicating specialized processing. Retailers sell devices without mentioning disposal obligations. When devices reach end of life, the burden falls on municipal waste systems never designed to handle them, on recycling workers who face injury from fires they cannot anticipate, on communities whose infrastructure burns while manufacturers book quarterly profits.

The cost-shifting has been remarkably successful.

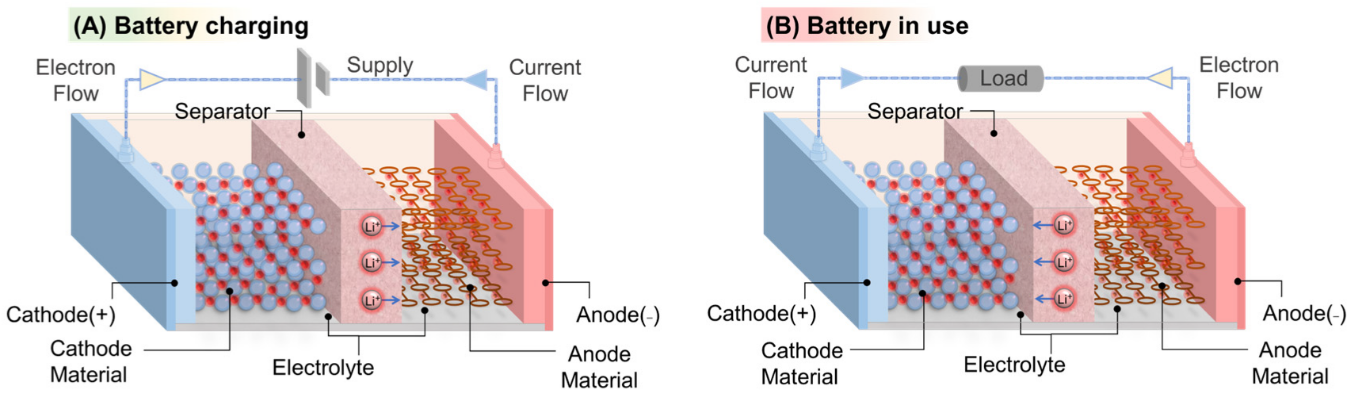

When a lithium-ion cell fails, the organic carbonate electrolytes inside vaporize and ignite. So far, conventional fire behavior. But then the cathode materials decompose under heat and release oxygen. The fire generates its own oxidizer. Water cannot extinguish it. Foam cannot smother it. The conflagration sustains itself even in environments that would suffocate any ordinary flame.

Thermal runaway proceeds through a cascade that, once initiated, cannot be stopped. Internal short circuits generate heat. Heat accelerates chemical decomposition. Decomposition releases more heat and flammable gases. Cell temperature climbs past 1,200 degrees Celsius.

In multi-cell battery packs, failure propagates from cell to cell.

Lithium battery fires can appear extinguished only to flare up hours or days later because internal chemical reactions continue beneath charred exteriors. Waste facilities have experienced three, four, five flare-ups from a single source. Firefighters who think they have contained the situation return to their stations. Then they get called back. A single battery in a garbage truck can destroy the vehicle, injure the driver, and ignite surrounding infrastructure before anyone understands what happened. Place this ignition mechanism in a waste stream containing paper and cardboard and plastics, and catastrophe becomes statistical certainty.

The slower failure receives less attention than the fires. Lithium batteries concentrate critical minerals in configurations already refined for electrochemical performance. Approximately 60% of global cobalt production originates from the Democratic Republic of Congo, extracted through operations involving child labor and unsafe mining practices that would trigger criminal prosecution in any developed nation. China dominates refining and processing.

Every battery that enters a landfill deepens dependence on these supply chains.

The contamination pathways extend across decades. Electrolyte solvents leach into soil and migrate toward groundwater. Heavy metals accumulate in sediments and enter food chains. Combustion products lodge in lung tissue. Agricultural land within contamination plumes suffers productivity losses that persist for generations. None of these costs appear on the receipt when consumers purchase a new smartphone.

The EPA classifies most lithium-ion batteries as hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Discarded cells typically qualify as ignitable and reactive. Household generators receive exemptions from hazardous waste requirements. This exemption made sense in an era when household hazardous waste meant a gallon of old paint and a can of motor oil.

It makes no sense now.

State-level regulations have emerged to fill federal gaps, but their fragmented character creates confusion. New York prohibits disposing of rechargeable batteries as solid waste and mandates retailer collection, with inconsistent enforcement. California operates comprehensive hazardous waste programs. Washington State permits universal waste handling while implementing extended producer responsibility legislation. The European Union's Battery Regulation establishes aggressive targets and traceability requirements. EPR implementation in the United States remains years behind the scale of the problem.

For anyone trying to dispose of batteries properly, identification comes first. Lithium batteries power the obvious devices: smartphones, laptops, tablets, power tools, electric vehicles. They also power wireless earbuds and fitness trackers and electric toothbrushes. They hide inside children's shoes that light up with each step. They animate singing greeting cards. They power vape pens that have become a disposal crisis unto themselves, with millions discarded annually by users who have no idea they contain lithium batteries.

Any device that charges via USB almost certainly contains a lithium cell.

Cover all exposed battery terminals with non-conductive tape immediately upon removing batteries from devices. This single step addresses the most common failure mode: accidental short circuits through contact with other batteries or metal objects. Visible swelling indicates internal gas generation from electrolyte decomposition. This condition is unstable and worsening. Transport swollen batteries to collection points immediately, placing each cell in a separate plastic bag within a non-conductive outer container. If batteries display active distress symptoms such as hissing, smoking, leaking, or unusual heat generation, move them outdoors to non-combustible surfaces, maintain distance, and contact hazardous waste authorities.

Never attempt to cool distressed batteries with water.

Elevated temperatures accelerate degradation and reduce the thermal margin before failure. Vehicle interiors during summer months can exceed temperatures that trigger thermal runaway in compromised cells.

The United States operates without unified national collection infrastructure. Retail drop-off programs constitute the most accessible channel. Call2Recycle coordinates collection networks spanning over 25,000 locations, and major home improvement and electronics retailers maintain collection stations. These programs help. They were never designed to handle current volumes. Collection bins occupy minimal floor space and receive inconsistent staff attention. The gap between batteries entering commerce and batteries reaching recycling remains enormous.

Municipal hazardous waste programs accept lithium batteries through permanent facilities or periodic collection events. Frequency and accessibility vary dramatically by jurisdiction. Manufacturer take-back programs provide direct recycling channels, with major electronics manufacturers operating mail-back programs or accepting returns at retail locations.

Pyrometallurgy uses high-temperature smelting. Batteries enter furnaces operating above 1,000 degrees Celsius. Cobalt, nickel, and copper recovery rates exceed 95%. Lithium partitions into slag phases rather than metallic output streams, with recovery rates below 50%.

This matters enormously.

Lithium is the bottleneck mineral for the energy transition, yet the dominant recycling technology throws away nearly half of it. Hydrometallurgy operates through aqueous chemical dissolution at lower temperatures, achieving lithium recovery rates reaching 90% or higher, but generates significant wastewater and demands extensive preprocessing. Redwood Materials processes approximately 90% of lithium-ion batteries recycled in North America. Not every retired battery requires immediate recycling. Batteries removed from electric vehicles frequently retain 70-80% of original capacity despite falling below automotive performance thresholds. Second-life applications repurpose these batteries for stationary energy storage and grid support. The economics appear compelling on paper. Degraded EV packs contain thousands of dollars worth of cells that can be repackaged for stationary applications at fractions of new battery costs. Second-life applications require testing, repackaging, integration, and monitoring that add costs not captured in optimistic projections. Battery packs designed for specific vehicles do not automatically suit alternative uses.

Second-life delays recycling rather than eliminating it.

Automated disassembly systems employing industrial robotics and computer vision are displacing manual processes, improving throughput while reducing worker exposure. Direct recycling technologies aim to preserve cathode crystal structures rather than decomposing them to constituent elements. Laboratory results show promise. Commercialization faces substantial hurdles. Solid-state battery development may eventually transform recycling by eliminating flammable liquid electrolytes. Solid-state commercialization has been perpetually imminent for two decades.

Manufacturers design devices for obsolescence rather than durability. They embed batteries that cannot be replaced. They resist extended producer responsibility through lobbying and litigation. They print recycling symbols on packaging without building collection systems.

Whether collection, second-life, and recycling systems can scale to match this growth is unknown.

The optimistic scenario requires sustained infrastructure investment, effective producer responsibility implementation, technological advancement, and behavioral change among hundreds of millions of consumers.

Current trajectories do not point toward the optimistic scenario.

A systematic inventory of lithium batteries in any household will likely reveal more cells than expected. Establishing a designated collection station, taping terminals immediately upon removing batteries from devices, identifying the nearest collection point, and establishing a transport schedule prevents batteries from accumulating indefinitely in drawers and closets where they age and degrade and increase in risk. Damaged or swollen batteries require immediate transport. Purchasing decisions matter. Devices with user-replaceable batteries extend product life and simplify disposal. Devices designed for durability reduce waste generation.

Individual disposal decisions cannot substitute for systemic change. Proper disposal protects waste workers from fires. It recovers materials that would otherwise be lost. It demonstrates demand for recycling infrastructure.

These are small contributions to large problems, but small contributions accumulate, and the alternative is negligence that has measurable consequences for people who work in waste facilities and live near them and depend on the recycling systems that battery fires destroy.