Procurement buys the battery. It wasn't until 18 months later that the operations department discovered the battery problem. Different budget cycles, different departments, different people. Same bad decisions get made over and over because nobody connects one to the other.

Someone pulls a spec sheet, matches voltage, picks the lowest bid, moves on. Reasonable approach if spec sheets predicted real-world performance. They do not. Cycle life ratings come from laboratory conditions with controlled temperature, precise discharge rates, ideal charging protocols. Warehouse conditions look nothing like that. Numbers on the page bear almost no relationship to how long that battery will actually run before it starts causing problems. Facilities keep buying the same batteries that keep failing early, then buying more of the same because the budget is wrecked from all the replacements.

Manufacturers test batteries under conditions that maximize reported numbers. A cycle life test might run at 25°C ambient with perfectly calibrated discharge rates and immediate recharge on a precise schedule. Real warehouses operate at whatever temperature the building happens to be. Discharge rates spike during acceleration and lifting. Charging happens when someone remembers to plug in the equipment or when the shift ends. This gap between laboratory and reality explains why two-year-old batteries fail when the spec sheet promised five years.

The Voltage Problem

A 36V battery in a 24V system will burn out the motor. Failure mode is dramatic and obvious. A 24V battery in a 36V system causes subtler damage that takes months to manifest. Motors strain to compensate for insufficient power, pulling excess current that degrades the drivetrain gradually. Neither mistake is recoverable. Both require replacing equipment that was working fine before someone installed the wrong battery.

Equipment nameplates show required voltage. But the only reliable method is measuring the existing battery with a multimeter before ordering replacements.

A distribution center in the Midwest skipped measurement. Purchased thirty batteries based on a faded label that someone in receiving glanced at and transcribed onto the order form. Label was wrong. Two years later those batteries remained in storage, unused, occupying valuable warehouse space because there was no compatible equipment anywhere in the operation.

Supplier refused returns because the order matched what was requested. Around twenty thousand dollars of dead inventory with no recovery path. Five minutes with a multimeter would have prevented the whole situation.

This mistake happens because batteries from different voltage classes often look identical. Same case dimensions. Same connector style. Similar weight. Nothing visible distinguishes a 24V unit from a 36V unit except the label and the measurements. Verification takes minutes. Consequences of skipping verification can persist for years.

Physical Dimensions and Weight Distribution

Compartments on pallet jacks are engineered around specific dimensions and weight. Units slightly too large get forced into compartments by technicians running behind schedule, cracking cases or stressing terminals in ways that cause intermittent failures for months afterward. Damage might not be visible. A hairline crack in the case admits moisture and contaminants that degrade cells gradually. A slightly bent terminal creates a connection that works most of the time but fails under vibration or heavy load.

Units too small shift during operation. Equipment accelerates, decelerates, turns, lifts, lowers. Each motion transfers force to the battery. Without secure mounting, the battery moves. Moving loosens connections. Loose connections develop resistance. Resistance builds heat. Eventually something arcs or melts.

Energy density advantages mean a 200 amp-hour lithium pack occupies perhaps 60% of the volume of a 200 amp-hour lead acid unit. Retrofitting lithium into compartments designed for lead acid creates slack that needs filling with brackets, spacers, or custom mounting hardware. Skip the mounting hardware and connector replacements become a recurring maintenance item that nobody can explain because the battery keeps testing fine on the bench.

Weight matters beyond simple fit.

Pallet jacks balance around the battery as counterweight. A lighter battery changes those characteristics in ways that experienced operators adapt to unconsciously. They adjust their movements without thinking about it. New operators do not know to compensate and sometimes tip equipment, damage product, or injure themselves.

Heavier batteries stress components in ways that accumulate over years. Bearings designed for one weight class wear faster when constantly supporting additional mass. Tires compress more under heavier loads and wear faster. Frames absorb more force with every stop and start, every lift and lower. Nothing fails immediately. Everything fails sooner than it should.

Connectors: The Overlooked Failure Point

Connectors carry every watt of power the system uses. That single junction point between storage and motor handles all energy flow. Undersized connectors build heat gradually. Resistance develops over weeks as contacts oxidize or pit. Heat accelerates oxidation. Oxidation increases resistance. This cycle continues until something fails.

Technicians can chase this problem for months. Battery tests fine on the bench. Controller tests fine on the bench. Motor tests fine on the bench. Intermittent failures only appear under load, when current flow is high enough to expose the marginal connection. Equipment comes back to the shop and everything checks out because test currents are lower than operational currents.

Discoloration or pitting on contacts usually indicates the connector was the original culprit. But finding that requires pulling the connector apart for visual inspection, which nobody does when the battery just tested fine.

One warehouse spent close to four months replacing batteries and controllers on equipment that kept cutting out during operation. Every component tested normal under standard diagnostic procedures. Root cause turned out to be oxidized contacts inside a connector that looked fine from outside. Months of diagnostic time, three unnecessary battery replacements, a controller swap that solved nothing. Nobody pulled the connector apart for visual inspection until someone from the supplier happened to mention it during an unrelated service call.

Capacity Ratings and Real-World Performance

Spec sheet capacity assumes discharge patterns that do not occur in actual warehouse operations.

Lead acid chemistry has a basic limitation: discharging below 50% causes sulfate crystal formation on the plates. During discharge, lead sulfate forms as part of the normal electrochemical reaction. During recharge, the sulfate should convert back. When discharge goes too deep or recharge waits too long, the sulfate crystallizes. Crystals start soft but harden over repeated deep discharge cycles into permanent formations that coat the plates and reduce active surface area.

Hardened sulfate is permanent. No additive or reconditioning service reverses it. Companies sell products claiming to dissolve sulfate buildup. None of them work on hardened crystals. A battery with severe sulfation is scrap regardless of age or original cost.

Degradation stays invisible until it becomes severe. Operators do not notice capacity dropping three percent per month. Equipment still runs through most of the shift. Runtime shrinks gradually. Operators unconsciously adjust expectations. Then one day the battery that used to run a full shift quits at 2 PM. By then the damage is irreversible and the battery needs replacement years before its design life should have ended.

Lithium chemistry tolerates 80-90% discharge without equivalent degradation mechanisms. Electrochemical processes work differently. Deep discharge does not cause permanent structural changes to the electrodes the way it does in lead acid. A 200 amp-hour lithium pack delivers 160-180 usable amp-hours throughout its service life.

Comparing nameplate capacity between technologies is misleading because the numbers measure different things. A nominally smaller lithium unit will outperform a larger lead acid unit in actual daily use when both are operated under real warehouse conditions.

Power draw varies dramatically during operation. Acceleration pulls several times the current of steady cruising. Lifting a loaded pallet draws more than traveling empty. Motor nameplates show peak draw, which occurs rarely in sustained operation, maybe during initial acceleration or lifting unusually heavy loads. Using 60-70% of nameplate as working average provides more realistic capacity planning.

A common sizing mistake: calculate capacity based on current operational needs, purchase units that exactly match, discover within a year that business growth has outstripped capacity. Warehouses handle more volume. Shifts run longer. Equipment runs harder. What barely covered yesterday's requirements cannot cover today's. Size for projected operations two or three years out.

Economics of Lead Acid vs. Lithium

A lead acid unit costs around $700. A comparable lithium unit costs around $2,500.

At first the decision seems obvious until the timeline extends past the first purchase. Under daily use, lead acid requires replacement every three years. Lithium runs eight to ten years. Purchase price advantage disappears during the first replacement cycle and reverses decisively by the second. Over a ten-year period, the $700 option requires three or four purchases while the $2,500 option requires one.

Lead Acid Battery

Initial Cost: ~$700

Lifespan: 3 years under daily use

10-Year Cost: $2,100–$2,800 (3-4 units)

Maintenance: 15-20 hours annually

Lithium Battery

Initial Cost: ~$2,500

Lifespan: 8-10 years

10-Year Cost: $2,500 (1 unit)

Maintenance: ~1 hour annually

Maintenance widens the gap further. Weekly water level checks, terminal cleaning, equalization charges: lead acid demands constant attention. Work is tedious, often performed in poorly ventilated areas where acid fumes make the task unpleasant. Tedious, unpleasant work gets skipped when operations get busy. Skipped maintenance destroys batteries faster than any other factor.

Water level is the most common failure point. Electrolysis during charging breaks water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Gases escape. Electrolyte level drops. When the level drops below the top of the plates, exposed plate material oxidizes in air instead of remaining submerged in electrolyte. Permanent capacity loss follows. A 200 amp-hour unit can become a 140 amp-hour unit after one bad stretch of neglected maintenance during a busy season. Recovery is not possible. Damage is structural.

Equalization charging gets neglected similarly. Sulfuric acid is denser than water. Over time and repeated cycling, acid concentration develops gradients, with stronger acid settling toward the bottom of each cell. Equalization cycles, controlled overcharging that causes electrolyte mixing through gas bubble agitation, remix the solution. Without periodic equalization, the bottom portion of plates operates in more concentrated acid than the top. Corrosion rates differ. Wear becomes uneven. Battery life shortens.

A single lead acid unit consumes fifteen to twenty hours of maintenance labor annually when maintenance is actually performed correctly. At loaded labor rates, that represents $500-700 per unit per year before any parts or materials. Multiply across a fleet and battery maintenance represents a significant personnel expense that appears nowhere in procurement analysis because it comes from a different budget.

Lithium maintenance consists of periodic connector inspection and occasional firmware updates on packs with smart management systems. Perhaps an hour annually per unit. Sometimes less.

Charging Logistics and Operational Impact

Charging takes six to eight hours with lead acid, followed by another six to eight hour cooling period before safe return to service. Putting a hot unit back to work causes thermal stress that accumulates as invisible internal damage. Electrolyte temperature exceeds optimal operating range. Chemical reaction rates change. Degradation accelerates. Units that should last three years die at eighteen months because the schedule never allowed proper cooldown.

Cooling requirements create logistical problems that compound with each shift added. One battery cannot support operations beyond eight hours. Two-shift operations need two batteries per machine. Three shifts need three. Each swap requires trained personnel who know the procedure, battery handling equipment that can move the weight safely, and a designated swap area with clearances for maneuvering.

Attempting to move a 130-150 kilogram battery by hand risks injury. Carts or overhead hoists handle the weight.

Each swap runs ten to fifteen minutes including travel to and from the charging area. Time adds up. Twenty pallet jacks running two shifts means roughly forty swaps daily. At twelve minutes average, that represents eight hours of labor daily devoted entirely to moving batteries rather than moving product. Every day. Every week. Every month.

Lithium charges in two to three hours with no cooling requirement.

Lithium chemistry handles heat differently. Cells tolerate returning to service immediately after charging. Opportunity charging during breaks and shift changes keeps units topped up throughout the day. One battery supports continuous multi-shift operation. Spare inventory for that same twenty-machine fleet drops from sixty units to twenty. Eight hours of daily swap labor disappears entirely. Operators can spend that time moving product instead of moving batteries.

Operators notice the difference even when they cannot articulate why. Weight reduction changes acceleration and handling characteristics. Eliminating the swap routine improves morale in ways that do not appear in productivity metrics but affect turnover, job satisfaction, and the willingness of experienced operators to stay rather than find work elsewhere.

Charging Infrastructure

Charging lead acid produces hydrogen gas. Hydrogen becomes explosive at concentrations as low as 4% in air. Managing that hazard requires dedicated ventilation systems calculated for the charging rate and number of batteries, explosion-proof electrical fixtures rated for hazardous locations, emergency safety equipment including eyewash stations and spill containment materials, and ongoing compliance monitoring. Building a compliant charging room from scratch runs tens of thousands of dollars depending on size and local code requirements. Retrofitting an existing space that was not designed for the purpose often costs more than new construction.

A cold storage facility discovered during routine inspection that their charging area did not meet current ventilation codes. Codes had changed since original construction. Retrofit cost close to fifty thousand and took six weeks, during which battery charging had to occur outdoors in a temporary enclosure regardless of weather. Operations continued, but at reduced capacity and with significant inconvenience.

Lithium charges from standard outlets with no special infrastructure. No dedicated room. No ventilation requirements. No explosion hazard. No regulatory compliance burden. Chargers can be positioned anywhere electrical service is available, next to the dock, in the staging area, wherever equipment naturally pauses during the workday.

Cold Environment Performance

Cold destroys lead acid performance.

Capacity drops approximately 1% per degree Celsius below 25°C. At -10°C, common in cold storage facilities, roughly 35% of nameplate capacity has already disappeared before any work begins. At freezer temperatures approaching -20°C, half the capacity is gone. Equipment rated for eight hours of runtime delivers four. Operations either accept reduced capacity or find workarounds.

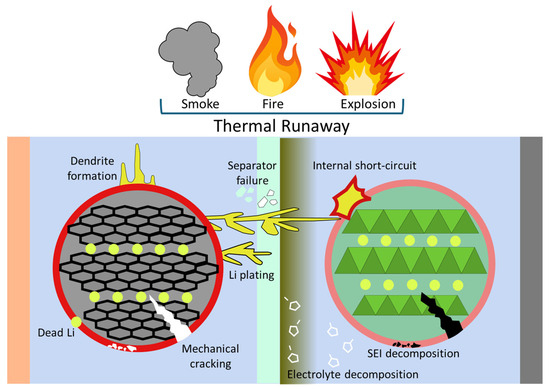

Charging below freezing causes a different problem. Lithium plating occurs when lithium ions deposit on the anode surface as metallic lithium instead of intercalating properly into the electrode structure. Plating reduces capacity permanently and can eventually cause internal shorts. Batteries damaged by cold charging may continue working for a while before failing unexpectedly.

Cold storage facilities using lead acid face constrained choices. Accept drastically reduced runtime that may not support operational requirements. Implement battery warming systems that add cost, complexity, and another maintenance obligation. Keep batteries warm in heated rooms and swap frequently, but that approach requires more units, more swap labor, more scheduling complexity, and the batteries cool during use anyway. Performance still degrades through the shift. By the time they return for charging they are often too cold to charge safely, requiring a warming period before the charging period before the cooling period. Scheduling becomes intricate.

Lithium loses minimal capacity in cold conditions relative to lead acid. Packs with integrated heating systems warm cells to optimal temperature before accepting charge, automatically and without operator intervention. Internal monitoring manages temperature and adjusts charging accordingly.

Management Systems in Lithium Packs

Management electronics determine whether a lithium pack delivers a decade of service or fails years early.

Each cell leaves the factory with slight manufacturing variations in capacity, internal resistance, and aging characteristics. Those variations amplify over charge-discharge cycles. Without active balancing, weaker cells get pushed past their limits while stronger cells operate comfortably below their capacity. Weakest cells determine pack behavior. One dead cell kills the entire pack.

Cheap lithium batteries cut costs on management system quality because the management electronics represent one of the most expensive components in the pack. Cells might be fine. Enclosure might be fine. Cooling system might be adequate. Management electronics might be insufficient to maintain cell balance over years of use. Spec sheets and marketing materials do not reveal this. Sales presentations focus on cell chemistry and capacity claims.

Temperature monitoring matters more than specifications suggest. Charging below freezing causes lithium plating on the anode. Capacity loss follows. Internal shorts become possible. A proper management system refuses charge until cells reach safe temperature. Packs monitor themselves and wait for conditions to improve before accepting current.

Cheap management systems skip the check because implementing temperature monitoring and charge control adds cost. Cells charge anyway. Damage accumulates.

Hot environments cause different problems. Cell aging accelerates with temperature. Electrolyte degrades faster. Capacity fades sooner. A management system that ignores temperature allows batteries to cook themselves in unventilated areas during summer months. Cells that should last ten years might last six or seven.

Sellers who cannot explain their management system in detail probably do not understand their own product. That becomes apparent when something fails and technical support is needed.

When Lead Acid Still Makes Sense

Daily usage under two hours. Budgets that genuinely cannot accommodate higher purchase prices under any financing arrangement. Facilities with existing lead acid infrastructure already depreciated and maintained by staff already employed for that purpose. All three conditions must apply simultaneously. That combination is uncommon.

Budget constraint arguments usually fail under analysis. So does the infrastructure argument. That charging room everyone feels obligated to keep using might actually cost more to maintain than abandoning it entirely. Ventilation systems require inspection and maintenance. Compliance documentation requires updates. That space could serve other purposes.

Financing deserves more attention than it receives. Lithium batteries cost more upfront but save money over time. That cash flow pattern is exactly what equipment financing handles. Operations that cannot write a check for $50,000 in lithium batteries can often lease them, spreading cost over service life while capturing savings immediately. Lease payments may be less than the maintenance and replacement costs being avoided.

Phased transitions work for operations not willing to convert everything at once. Start by replacing highest-use equipment where the economics are most favorable. As lead acid fleets age out, replace retiring units with lithium rather than buying more lead acid. This approach spreads capital investment over years while building operational experience. Each conversion demonstrates savings that justify the next. Early lithium batteries become proof of concept that makes subsequent approvals easier.

Creative supplier arrangements exist too. Service models where suppliers retain ownership and charge per month or per cycle, transferring performance risk from facility to supplier. Trade-in programs accept old lead acid batteries as partial credit toward lithium purchases. Economics have more flexibility than a simple price comparison suggests.

Purchasing Inertia

Markets moved away from lead acid years ago. Technical arguments resolved. Economic arguments resolved. Purchasing inertia remains.

Procurement departments that have always purchased lead acid continue purchasing lead acid because the process is established. Spec sheets are familiar. Suppliers are familiar. Approval workflows exist. Switching to unfamiliar technology requires someone to propose change, justify the proposal, work through approval processes, and accept responsibility if something goes wrong. Risk-taking is not what procurement departments typically reward.

Purchase decisions sit with someone who sees a spec sheet comparison, notices the price difference, and selects the lower number because that is the evaluation criterion they operate under. Getting the right information to the right decision-maker is half the problem.

A maintenance technician telling procurement that lithium is worth additional cost may not carry weight. Technicians are not purchasing authorities. Same information presented as a five-year total cost analysis showing savings over time might change the conversation. Framing matters. Decision-makers need to see justification in terms they use and metrics they track.

Supplier relationships reinforce existing patterns. Sales representatives who have been calling for fifteen years sell lead acid because that is what their company manufactures or distributes. Recommending lithium might mean recommending a competitor's product, not something that helps the representative's commission or relationship with their employer. Selling what has always been sold is the path of least resistance.

Equipment manufacturers sometimes complicate matters by specifying lead acid in their documentation. Specifications are often years old, written when lithium was expensive and unproven for industrial applications. Official specs create hesitation about warranty implications. Those concerns are usually unfounded. Calling manufacturers directly to ask about lithium compatibility typically resolves the question in minutes. Spec sheets say lead acid because they were written in 2015 and never updated.

Supplier Selection

Who handles warranty claims? Where do replacement parts come from? What happens when a battery fails at thirteen months, past standard warranty but well before expected end of life? The answers separate transactional suppliers from relationship suppliers.

This market includes legitimate established companies and operations that disappear after a few years. Low prices sometimes come from vendors who will not exist when warranty claims arise. References separate reliable suppliers from the rest. Any legitimate supplier can provide contact information for existing customers willing to discuss their experience.

Inspect batteries before accepting delivery. Damaged cases, bent terminals, specifications that do not match the order. Shipping damage occurs more often than vendors admit. Order errors occur more often than purchasing departments expect. Catching problems at the receiving dock is easier than catching them after installation when equipment starts malfunctioning and nobody remembers what the battery looked like when it arrived.

Total Cost Reality

A $2,500 battery that lasts ten years costs $250 annually in acquisition. A $700 battery that lasts three years costs $233 annually in acquisition alone, before maintenance labor, before energy efficiency differences, before infrastructure costs, before swap logistics, before downtime losses. Adding those factors, the $700 battery costs roughly twice as much per year as the $2,500 battery.

Cash flow is the usual objection. The $700 unit leaves money in the current quarter's budget. The $2,500 unit requires explanation, approval, possibly a financing arrangement. Making a different decision requires effort. Easier to continue doing what has always been done even when what has always been done costs more in the long run.

Real costs hide in different budget lines, spread across years, absorbed by departments that do not communicate with each other. Procurement sees purchase price. Maintenance sees labor hours. Operations sees equipment downtime. Finance sees utility bills and charging infrastructure costs. Nobody totals it until someone forces the conversation.

Voltage, dimensions, capacity for actual use patterns. The technical requirements are not difficult. The difficult part is getting complete information in front of the person signing the purchase order.