LiFePO4 vs NMC vs LTO Battery Comparison

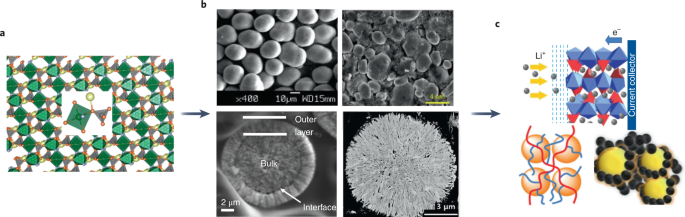

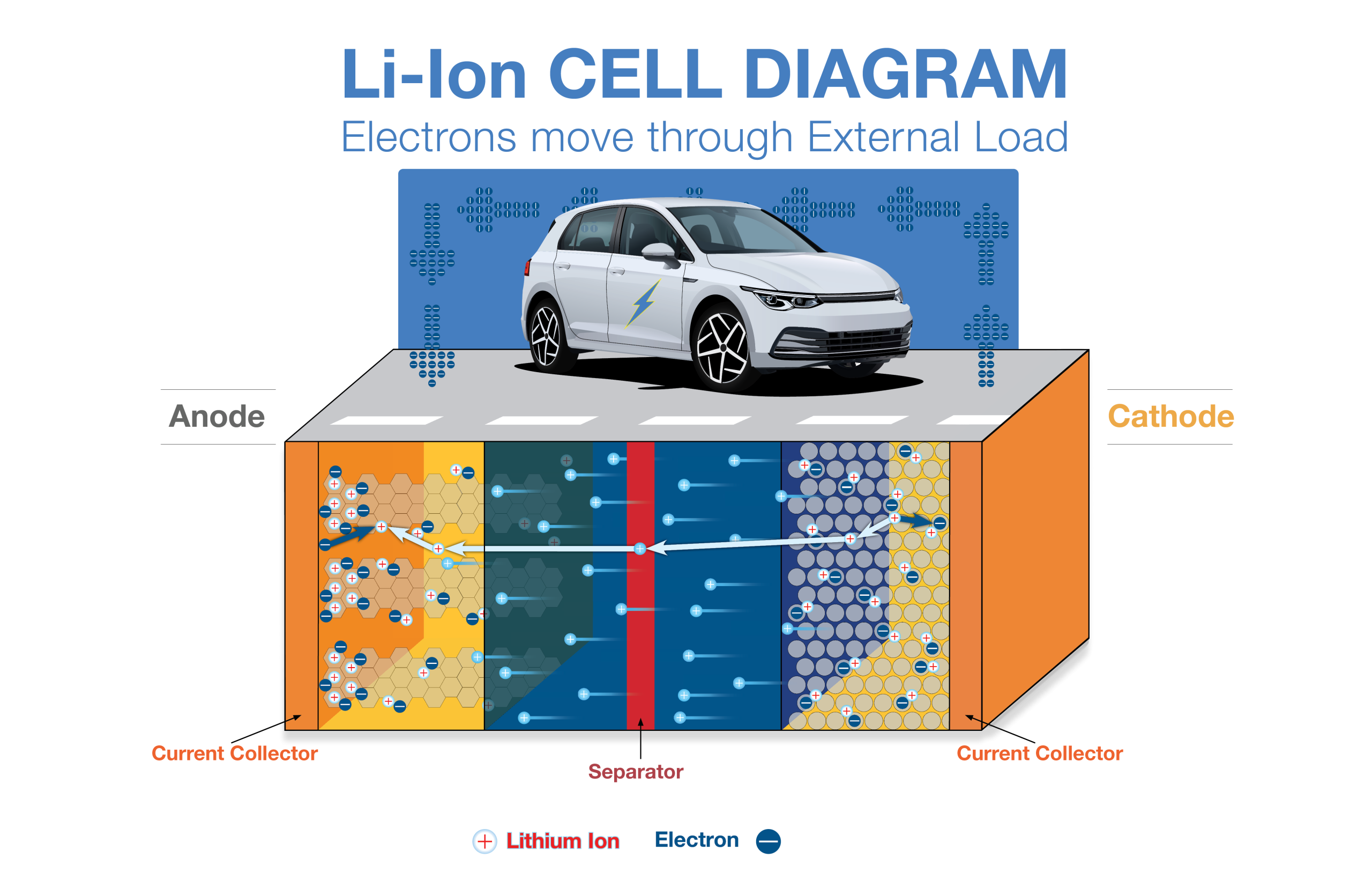

LiFePO4, NMC, and LTO refer to three lithium-ion battery chemistries that have carved out different territories in the market. The names come from their electrode materials. LFP uses lithium iron phosphate as the cathode. NMC uses nickel-manganese-cobalt oxide. LTO is the odd one because it changes the anode rather than the cathode, swapping graphite for lithium titanate.

Modern lithium-ion battery technology powers everything from smartphones to grid-scale energy storage

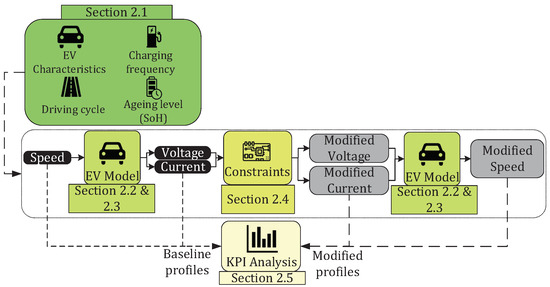

Most comparisons of these chemistries present a table with energy density, cycle life, safety rating, and cost, then declare that each has its place. This is true but not very useful. The more interesting questions are why the market evolved the way it did, what the actual failure modes look like, and where the conventional wisdom gets things wrong.

How We Got Here

The history matters because it explains why certain chemistries dominate certain applications, and why that might change.

LFP has an interesting origin story. John Goodenough, who had already co-invented the lithium cobalt oxide cathode that made the original Sony lithium-ion batteries possible, identified lithium iron phosphate as a cathode material at UT Austin in 1996. The material looked promising on paper: iron is cheap and abundant, the phosphate structure is thermally stable, and the theoretical capacity was reasonable.

The problem was that the material barely conducted electrons or ions. The olivine crystal structure confines lithium to one-dimensional channels. Block a channel with a defect, and you block the whole pathway. Bulk electronic conductivity was around 10⁻⁹ S/cm, which is about eight orders of magnitude too low. Early LFP cells had terrible rate capability. You could not charge or discharge them fast enough to be useful.

Battery chemistry breakthroughs often emerge from decades of materials science research

The breakthrough came from work by Michel Armand and others on carbon coating and nanoparticle synthesis. Coat each particle with a thin carbon layer to provide electron conductivity. Shrink the particles to nanoscale to reduce diffusion distances. By the mid-2000s, A123 Systems in Massachusetts was shipping LFP cells that could handle 30C discharge rates. The company raised hundreds of millions in venture capital, went public, won a major contract to supply batteries for the Fisker Karma, and then went bankrupt in 2012 when Fisker collapsed. The technology survived; the Chinese company Wanxiang bought A123's assets and continued development.

The reason to tell this story is that LFP's commercial success required solving a materials science problem that many people thought was fundamental. The olivine structure does have one-dimensional diffusion channels. That limitation does not go away. But clever engineering found ways to work around it. This pattern shows up repeatedly in battery development: what looks like a hard constraint turns out to be an engineering problem, or what looks like an engineering problem turns out to be a hard constraint. Telling the difference in advance is difficult.

NMC has a different history. It evolved from LiCoO2, the original lithium-ion cathode material. The layered oxide structure conducts lithium well, but cobalt is expensive and supply is concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo with all the ethical and geopolitical complications that implies. Substituting cheaper metals while maintaining or improving performance drove the development of NMC formulations.

The naming convention encodes the metal ratios: NCM111 has equal parts nickel, manganese, and cobalt, NCM523 is 5:2:3, NCM622 is 6:2:2, NCM811 is 8:1:1. The trend has been toward higher nickel content because nickel contributes to capacity. NCM811 delivers over 200 mAh/g versus about 160 mAh/g for NCM111.

This trend has a cost. Higher nickel content means less structural stability. The charged cathode wants to release oxygen. The surface reconstructs during cycling. The material is pushing against thermodynamic limits in ways that LFP is not. More on this below.

LTO came from a different direction entirely. The idea was not to improve the cathode but to fix problems with the graphite anode. Graphite works well enough for most applications, but it operates at 0.1V versus lithium metal. That is perilously close to the potential where lithium plates out as metal rather than intercalating into the graphite structure. Fast charging, cold temperatures, or aged cells can push the anode potential below zero, causing lithium plating. Plated lithium can form dendrites. Dendrites can pierce separators and cause internal short circuits.

Battery chemistry choice fundamentally shapes the charging experience for electric vehicle owners

Lithium titanate operates at 1.55V versus lithium. That 1.45V of additional margin makes lithium plating thermodynamically impossible under any realistic operating condition. The tradeoff is severe: cell voltage drops by 1.45V, which directly cuts energy density by 35-40% before considering other factors.

Toshiba commercialized LTO cells under the SCiB brand starting around 2008. Production volumes have remained small. The energy density penalty limits applications to those where other factors dominate. More on this below as well.

The Safety Question

Safety is where the chemistries diverge most dramatically, and where the conventional comparison tables are most misleading.

The standard presentation lists thermal runaway onset temperatures. LFP: around 270°C. NMC: around 200°C for high-nickel versions. This makes it sound like NMC is somewhat worse. The reality is that the failure modes are qualitatively different.

When an NMC cathode gets hot enough, oxygen starts coming off the crystal lattice. This is not a minor side reaction. The oxygen reacts with the electrolyte exothermically, generating heat that destabilizes more cathode material, releasing more oxygen. The reaction is autocatalytic. Once it starts, it accelerates. Peak temperatures can exceed 800°C. The cell can go from normal operation to violent failure in seconds.

Grid-scale battery installations require careful consideration of thermal management and safety systems

The McMicken energy storage facility in Arizona demonstrated what this looks like at scale. In April 2019, a single cell in a 2 MWh NMC installation went into thermal runaway. The fire propagated through the battery racks. When firefighters opened the door to the container, the accumulated flammable gases ignited in an explosion that sent four firefighters to the hospital with burns and injuries. One was in critical condition for weeks.

LFP does not fail this way. The phosphate group holds onto its oxygen much more tightly than the layered oxide structure. You can heat LFP to high temperatures and it will decompose eventually, but it does not release oxygen to feed an accelerating reaction. The energy release is smaller. The peak temperatures are lower. Fires involving LFP installations have occurred, but the failure mode is typically gradual rather than explosive.

The comparison between LFP and NMC safety is not a matter of one being somewhat better than the other. They are qualitatively different. An NMC thermal runaway is a combustion event where the cathode supplies both fuel and oxidizer. An LFP failure is a decomposition event where external oxygen is required to sustain combustion.

For LTO, the safety story is different again. The anode is the main concern here. By eliminating the possibility of lithium plating, LTO removes the most dangerous failure mode on the anode side. Internal short circuits from dendrite growth cannot happen. The overall cell safety then depends on the cathode chemistry used, but the anode contribution to risk is essentially zero.

The practical implications of these safety differences extend beyond the batteries themselves. NMC packs require elaborate thermal management systems: liquid cooling to remove heat during fast charging, thermal barriers between cell groups to slow propagation, venting pathways to direct hot gases away from vehicle occupants, BMS algorithms that monitor for early signs of trouble. All of this adds mass, cost, and complexity.

LFP packs can often use simpler air cooling. Thermal barriers can be lighter because propagation is less likely. The engineering overhead is lower. When people compare energy density between NMC and LFP at the cell level, they often forget that the pack-level comparison looks different once all the safety hardware is accounted for.

This is one area where the industry narrative has been misleading. For years, the emphasis on energy density as the primary metric implicitly treated safety concerns as engineering problems to be solved. The McMicken explosion and subsequent incidents have shifted perception, but the underlying physics has not changed. NMC cathodes have always released oxygen when overheated. That is not a bug to be fixed; it is a consequence of the layered oxide crystal structure.

Degradation and Lifetime

Cycle life numbers in datasheets should be treated with skepticism. They are measured under favorable conditions that may not reflect real-world use.

NMC degradation involves multiple simultaneous mechanisms, which makes lifetime prediction complicated. The surface of the cathode particles transforms from the original layered structure into a rock-salt phase that does not conduct lithium ions well. This happens because the delithiated surface is thermodynamically unstable. Nickel ions, which have similar ionic radius to lithium, migrate into lithium sites in a process called cation mixing. Once enough mixing occurs, the layered structure collapses locally.

Electric vehicle owners experience battery degradation differently depending on chemistry and usage patterns

This surface reconstruction creates a growing resistive layer. The cell impedance increases. Power capability drops. Owners of NMC-based EVs sometimes notice that the car feels sluggish at high states of charge before the range gauge shows serious degradation. This is the rock-salt layer making itself felt.

Manganese dissolution adds another pathway. At elevated temperatures, manganese can leach from the cathode into the electrolyte. The dissolved manganese migrates to the anode and catalyzes SEI decomposition. Cathode problems thereby cause anode problems. The degradation mechanisms are coupled.

Calendar aging matters too. NMC cells stored at high state of charge degrade even without cycling. The cathode potential in the charged state is high enough to drive continuous electrolyte oxidation. A fully charged NMC cell stored for a year at warm temperatures can lose 8-12% capacity without ever being used. This is why EV manufacturers often recommend not charging to 100% for daily use.

LFP degradation is simpler. The olivine structure is stable. The cathode does not undergo the surface reconstruction that plagues layered oxides. The main degradation mechanism is lithium inventory loss to SEI growth at the graphite anode. This is the same mechanism that affects all graphite-anode lithium-ion cells, but without the cathode-side complications, lifetime prediction is more straightforward.

The flat voltage curve of LFP creates a different problem. Between about 20% and 80% state of charge, the voltage changes by only 50-80mV. This makes state of charge estimation difficult. You cannot simply look at voltage and know how full the battery is. BMS algorithms rely on current integration (coulomb counting), which accumulates error over time. The result is that LFP systems sometimes display erratic state of charge readings until a full charge cycle allows recalibration.

LTO degradation is minimal compared to either LFP or NMC. The zero-strain property means particles do not crack during cycling. The high operating potential means SEI is thin and stable. The absence of lithium plating means no dead lithium accumulates. Cycle life exceeding 15,000 cycles has been demonstrated. Some frequency regulation installations report even higher numbers.

The cycle life advantage of LTO over other chemistries is not incremental. It is roughly an order of magnitude. For applications with high utilization rates, this translates directly into different economics. A bus that cycles twice daily will go through 7,000 cycles in ten years. NMC might need battery replacement twice in that period. LFP might need one replacement. LTO would likely outlast the vehicle.

Cold Weather

Cold weather performance deserves separate discussion because it affects real-world usability in ways that do not show up in standard specifications.

LFP has the worst cold weather performance of the three chemistries. At -20°C, capacity might drop to 50-60% of rated values. The one-dimensional diffusion channels in the olivine structure have high activation energy; ion mobility drops sharply as temperature decreases. Worse, charging at low temperatures risks lithium plating on the graphite anode even at moderate charge rates.

Cold climate performance varies dramatically between battery chemistries

Norwegian EV owners with LFP vehicles have complained about this. Norway has high EV adoption rates and cold winters, which makes it a good test case. The issue is not just reduced range but reduced charging speed. Attempting to fast charge a cold LFP pack either triggers protective limits that slow charging to a trickle, or risks damaging the battery.

The mitigation is battery preheating. Modern LFP EVs can warm the pack before charging using resistive heaters or heat pump systems. This works but takes time and energy. A driver arriving at a fast charger after a cold night might wait 20-30 minutes for the pack to warm up before charging begins at full speed. Range specifications do not mention this.

NMC handles cold weather somewhat better. The layered oxide structure has lower activation energy for diffusion. Capacity retention at -20°C is typically 70-80% rather than 50-60%. The graphite anode limitation for charging is the same as LFP, but the warmer cathode kinetics help.

LTO is the clear winner in cold weather. Capacity at -30°C can still reach 70-80% of room temperature values. More importantly, charging at low temperatures does not risk lithium plating because the anode potential never approaches the plating threshold. LTO systems can operate in arctic conditions without the preheating requirements that constrain LFP and NMC.

This is why electric buses in Scandinavian cities often use LTO despite its higher cost and lower energy density. The alternative would be either accepting severely degraded winter performance or installing elaborate battery heating systems that add weight, complexity, and energy consumption.

Where Each Chemistry Ends Up

The market segmentation that has emerged reflects these technical differences, though not always in obvious ways.

NMC dominates applications where energy density cannot be compromised. The Lucid Air needs its 500+ mile range to compete with gasoline vehicles. The phone in your pocket cannot afford to be thicker. These applications absorb the costs of thermal management and accept the cycle life limitations because the alternative is not meeting basic requirements.

Consumer electronics are entirely NMC territory and will remain so. The energy density gap between NMC and alternatives is simply too large. Nobody will carry a 30% thicker phone to get better cycle life.

Premium electric vehicles rely on high-energy-density NMC batteries to achieve competitive range figures

Premium EVs are similar. Range anxiety is real and range sells cars. Tesla uses NMC or NCA for Model S and Model X. So does Porsche for the Taycan, Mercedes for the EQS, Lucid for the Air. The customers for these vehicles are paying premium prices and expect premium range.

LFP has captured the standard-range EV segment and is expanding into commercial vehicles and grid storage.

Tesla's shift to LFP for standard-range Model 3 and Model Y in China and Europe mattered not because Tesla is a trendsetter but because it validated a different optimization. The standard-range customer, Tesla apparently concluded, cares more about price than about maximum range. LFP's lower cost, longer calendar life, and simpler thermal management outweigh its energy density disadvantage for this segment.

Chinese manufacturers, particularly BYD, have pushed LFP aggressively. BYD's Blade Battery uses a cell-to-pack architecture with long thin cells that improve pack-level density while maintaining LFP's safety advantages. BYD has become the second-largest EV manufacturer globally while using almost exclusively LFP chemistry.

Grid storage has converged on LFP even more decisively. A utility-scale storage project has different requirements than a vehicle. Space and weight constraints are minimal. Cycle life matters a lot because these systems cycle daily for 15-20 year project lifetimes. Safety matters enormously because a 100 MWh facility contains enough energy to cause catastrophic damage if it fails violently.

After the McMicken incident and subsequent NMC storage fires, the industry has become cautious about NMC at grid scale. Insurance costs for NMC installations have increased. Some jurisdictions have tightened permitting requirements. LFP's lower energy density is irrelevant for stationary applications; its better safety and longer cycle life are decisive advantages.

LTO occupies niches where its unique properties justify its cost premium.

The Geneva bus system is a good example. Buses equipped with roof-mounted charging contacts recharge for 5-10 minutes at terminal stops. A 60 kWh LTO pack can accept 600 kW at 10C. Five minutes delivers 50 kWh, enough for another 30-40 km. The bus carries a smaller battery because it recharges constantly. The pack will outlast the bus. NMC or LFP could not survive this duty cycle.

Electric transit systems often choose LTO batteries for their exceptional cycle life and fast-charging capability

Frequency regulation for electrical grids is another niche. Grid operators need fast-responding assets that can charge and discharge rapidly many times per day. A frequency regulation system might cycle 20 times daily. At that utilization rate, LTO's cycle life advantage dominates the economics despite higher upfront cost.

Cold-climate applications sometimes justify LTO as well. Mining vehicles in northern Canada, research stations in Antarctica, telecommunications equipment in Siberia. When the temperature drops to -40°C and the equipment must work, LTO's cold weather capability has value that outweighs its energy density penalty.

The boundaries between chemistry domains continue to shift as costs change and technology develops.

LFP costs have fallen faster than NMC costs since 2020. CATL and BYD together produce more LFP capacity than the rest of the world combined. Scale economics favor LFP as long as this production concentration continues. If LFP costs continue falling relative to NMC, the crossover point between the chemistries will shift further toward LFP in vehicle applications.

Sodium-ion batteries may eventually compete with LFP at the low end. CATL announced sodium-ion production in 2023. The technology offers potentially lower costs than LFP with similar safety characteristics but lower energy density. For applications where LFP's energy density is already acceptable, sodium-ion could undercut on price.

NMC development continues pushing toward higher nickel content. NCMA formulations with 90%+ nickel are in development. Single-crystal cathode particles show better stability than polycrystalline approaches. Each increment of nickel delivers less additional capacity while requiring more stability engineering. The returns are diminishing but not yet exhausted.

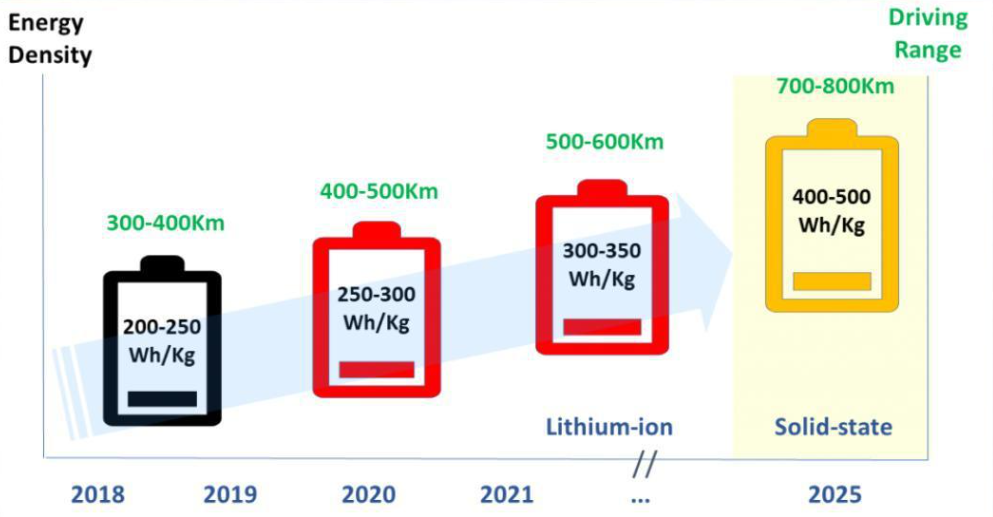

Solid-state electrolytes have been promised as a solution to NMC's safety issues for over a decade. The idea is to replace flammable liquid electrolyte with solid ceramic or polymer electrolyte, enabling lithium metal anodes without dendrite risk. Progress has been slower than projections. Interface resistance between solid electrolyte and cathode particles remains problematic. Toyota and others keep announcing production timelines that slip. The technology may arrive eventually. It has been "five years away" for fifteen years.

LTO will likely remain a specialty product. The energy density limitation is fundamental to the chemistry. Cost reduction through manufacturing scale would require a high-volume application, and the applications where LTO excels are inherently niche markets. This is not a criticism; some technologies serve niche markets well without ever going mainstream.

The fundamental constraints imposed by electrode chemistry limit how far the boundaries can shift. Higher energy density means more reactive materials at higher potentials. Safer chemistries mean lower voltages and less reactive materials. The tradeoffs follow from thermodynamics. Different chemistries represent different points on the tradeoff surface, and applications sort themselves to the points that match their requirements.