Lithium extraction from batteries denotes the recovery of lithium compounds from spent or end-of-life electrochemical cells—a process that bears no resemblance to the naive image of cracking open a battery and scooping out metallic lithium. The lithium in rechargeable batteries exists exclusively in ionic form, chemically bound within crystal lattices and dissolved in organic solvents. Liberating this lithium demands breaking thermodynamically stable bonds, navigating complex phase transitions, and managing materials that react violently with moisture and air.

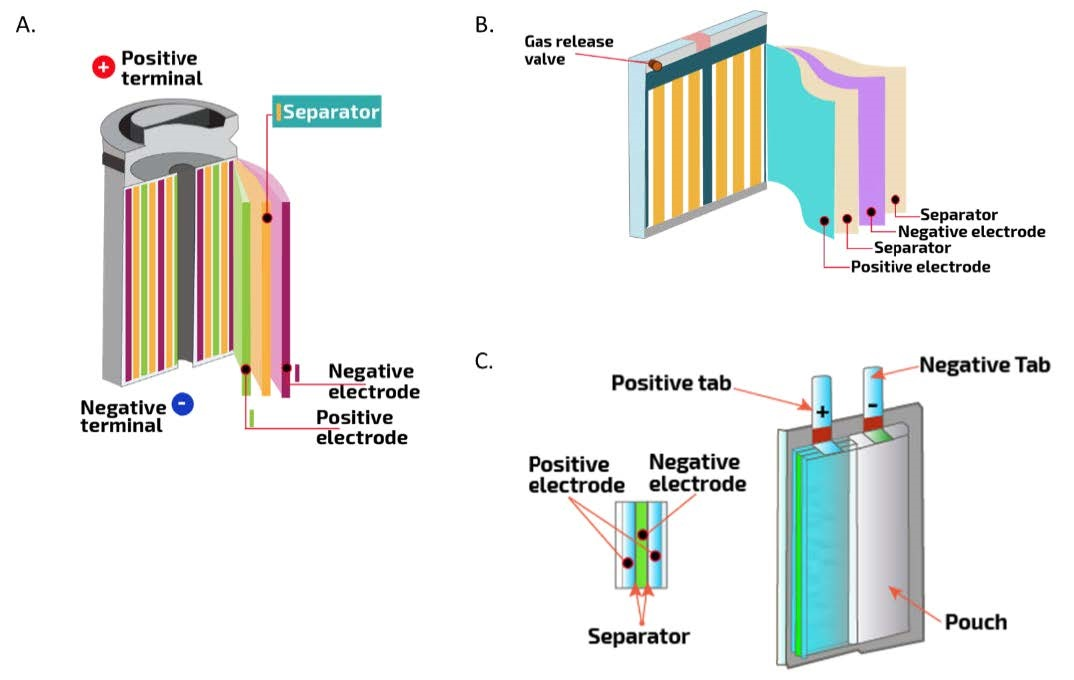

Modern lithium-ion cells distribute lithium across multiple components in fundamentally different chemical states. The cathode material—the primary lithium reservoir—contains lithium intercalated within transition metal oxide frameworks. In lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2), lithium ions are basically sandwiched between layers of cobalt and oxygen atoms—diagrams showing the crystal structure reveal what looks like a microscopic layer cake. The bonds holding lithium in place are incredibly strong, which is why one cannot simply grind up a battery and wash out the lithium. Lithium manganese oxide spinels (LiMn2O4) and olivine-structured lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) present analogous extraction challenges, with lithium embedded within three-dimensional tunnel structures or one-dimensional channels that resist dissolution.

Professional lithium extraction requires sophisticated laboratory equipment and safety protocols

The electrolyte carries lithium as solvated ions—typically lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) coordinated by carbonate molecules in a delicate chemical equilibrium. This mobile lithium fraction, though representing only 3-5% of total cell lithium, presents unique hazards. LiPF6 hydrolyzes instantly upon moisture contact, generating hydrogen fluoride gas capable of etching glass and causing severe pulmonary damage at concentrations below 30 parts per million.

Research published in Nature Communications establishes that lithium constitutes 2-7% of battery mass depending on cathode chemistry—a modest percentage that nonetheless represents substantial value at industrial scale. The extraction challenge lies not in the quantity but in the chemical intimacy between lithium and other battery constituents. Separating lithium from cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, aluminum, graphite, polymer binders, and decomposed electrolyte residues requires sequential chemical operations executed with precision.

Market dynamics amplify the extraction imperative. Lithium carbonate prices have fluctuated significantly—figures range from $80,000 to $150,000 per metric ton depending on timing and index referenced. The 2022 spike was dramatic, and things have cooled somewhat since then, but the general trend still points toward supply constraints. Geopolitical tensions surrounding lithium-producing regions exacerbate concerns, and EV manufacturers keep scaling up regardless of what the spot price does.

Why Individual Lithium Extraction Is Problematic

Attempting to extract lithium from batteries outside professional facilities constitutes a dangerous exercise in chemical ignorance. The risks span immediate physical harm, chronic health effects, legal liability, and environmental contamination—consequences entirely disproportionate to any conceivable benefit.

Lithium-ion batteries concentrate enormous chemical energy within compact packages. A fully charged 18650 cell stores around 10 watt-hours—calculations show that releasing this energy instantaneously could theoretically accelerate a kilogram mass to approximately 270 m/s.

This energy resides in the electrochemical potential difference between graphite anode and metal oxide cathode, separated by a polymer membrane mere micrometers thick. Physical damage to this membrane initiates thermal runaway: an autocatalytic cascade where exothermic decomposition reactions generate heat that accelerates further decomposition.

The EPA classifies lithium-ion batteries as ignitable and reactive hazardous wastes under RCRA criteria, assigning waste codes D001 and D003. Thermal runaway temperatures exceed 600°C within seconds of initiation, far surpassing the autoignition temperature of surrounding materials. The decomposition products include carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, methane, ethylene, and—most insidiously—hydrogen fluoride generated from fluorinated electrolyte salts and binder materials.

Proper safety equipment is essential when handling hazardous battery materials

Hydrogen fluoride requires particular attention because most people do not appreciate how dangerous this substance is. Unlike most acids that cause immediate pain upon contact, dilute HF penetrates skin without sensation, destroying tissue and binding calcium ions hours after exposure. There are case reports of digit amputations following exposures that victims initially dismissed as minor skin contact. The gas-phase HF released during battery fires causes pulmonary edema at concentrations that cannot even be detected by smell.

The electrolyte solvents—ethylene carbonate, diethyl carbonate, dimethyl carbonate—possess flash points between 18°C and 31°C. These volatile organics vaporize rapidly when cell integrity fails, creating explosive atmospheres in confined spaces. A single punctured laptop battery can fill an average room with flammable vapor within minutes. Standard household fire extinguishers prove ineffective or counterproductive; water application to lithium metal fires generates hydrogen gas and intensifies combustion.

The chemistry required for lithium extraction operates at a sophistication level incompatible with amateur implementation. Cathode materials require either extreme temperatures to break metal-oxygen bonds or aggressive chemical environments to dissolve the oxide matrix selectively. Neither approach translates to kitchen-table chemistry.

Pyrometallurgical liberation of lithium demands temperatures exceeding 1,200°C sustained for hours—conditions achievable only in industrial furnaces with refractory linings and controlled atmospheres. At these temperatures, lithium volatilizes preferentially, requiring specialized capture systems to prevent atmospheric loss.

Hydrometallurgical approaches appear superficially accessible—after all, acids are commercially available. However, efficient lithium dissolution requires concentrated mineral acids at elevated temperatures, generating corrosive aerosols and toxic gases. Sulfuric acid leaching produces sulfur dioxide when contacting residual organics. Hydrochloric acid generates chlorine gas under oxidizing conditions. Nitric acid attacks any organic matter present, including human tissue.

An Oak Ridge National Laboratory paper from 2022-2023 demonstrates that optimal lithium extraction occurs within pH ranges of roughly 5-11 at temperatures around 140°C. Maintaining these conditions requires temperature-controlled reaction vessels, continuous pH monitoring, and real-time chemical addition systems. Such equipment costs tens of thousands of dollars at minimum, plus specialized training to operate safely.

Beyond dissolution, purification poses equally formidable challenges. The leach solution contains lithium alongside cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, aluminum, and iron ions. Separating lithium from this mixture demands sequential precipitation, solvent extraction, or ion exchange operations. Each step requires precise chemical control. Contaminated lithium carbonate—containing even single-digit percentage impurities—possesses no commercial value and cannot be safely disposed through municipal waste systems.

The mathematics here are brutal. A smartphone battery contains maybe half a gram to one gram of lithium distributed across cathode, electrolyte, and anode interface layers. At current market prices, that represents perhaps $0.10-$0.30 in theoretical value—before accounting for chemicals, equipment, time, protective gear, waste disposal, and the very real possibility of injury.

The economics that truly undermine amateur extraction: a single pair of chemical-resistant gloves suitable for acid handling costs more than the lithium recoverable from a hundred phone batteries. Laboratory-grade sulfuric acid runs about $0.50 per battery equivalent. Waste neutralization adds similar costs. By the time protective eyewear, respiratory protection, and appropriate workspace preparation are factored in, thousands of batteries would need to be processed just to break even—at which point an amateur project transforms into a regulated industrial operation requiring permits, insurance, and compliance programs.

Industry analysis confirms that extracting lithium from batteries costs roughly five times more than mining lithium from spodumene deposits or evaporating lithium from brine sources. Professional recyclers achieve economic viability only through massive scale, recovering multiple valuable metals simultaneously, and optimizing logistics across continental collection networks.

Lithium-ion battery disassembly triggers regulatory obligations in most jurisdictions. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act subjects battery recycling operations to hazardous waste generator requirements, and facilities processing more than 100 kilograms monthly typically require EPA identification numbers and manifest systems for waste tracking. Violation penalties can reach $25,000 per day. State regulations add additional requirements that vary significantly by location. California appears stricter than most jurisdictions. Anyone considering battery processing at scale should consult with environmental law specialists.

How the Professionals Do It

Professional lithium recovery operations deploy three primary methodologies, each representing decades of metallurgical refinement. The industry draws distinctions between "pyro" and "hydro" approaches, though most real facilities use some combination.

Pyrometallurgical Methods

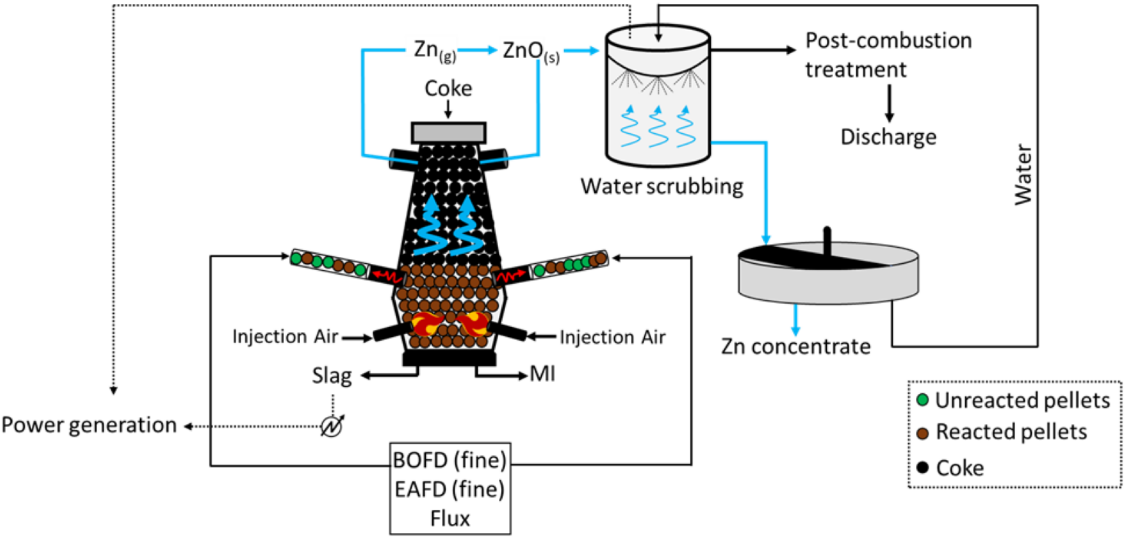

Pyrometallurgical methods subject battery materials to extreme thermal environments. This is essentially high-tech smelting—the lineage traces back to ancient metallurgy, but the process control and emissions management are thoroughly modern.

Industrial furnaces operate at temperatures between 1,000°C and 1,400°C for pyrometallurgical processing

Industrial facilities feed shredded batteries into rotary kilns, shaft furnaces, or submerged arc furnaces operating between 1,000°C and 1,400°C. At these temperatures, organic components combust or pyrolyze. Metallic components undergo sequential phase transitions. Aluminum melts at 660°C and floats atop denser materials. Copper melts at 1,085°C, forming a distinct liquid phase. Cobalt, nickel, and iron coalesce into alloys that sink to furnace bottoms. Lithium, with its relatively low boiling point of 1,342°C and high affinity for oxygen, partitions primarily into the slag phase.

Umicore's operation in Hoboken, Belgium, is probably the best-known example. The facility processes something like 7,000 tons of lithium-ion batteries annually, recovering cobalt and nickel as alloys while concentrating lithium in slag. This slag ships to partner facilities for hydrometallurgical lithium extraction—a hybrid approach that captures pyrometallurgy's feedstock flexibility while enabling high-purity lithium recovery.

The environmental profile is complicated. High-temperature operations consume substantial energy—generating significant carbon dioxide emissions unless powered by renewable electricity. Organic battery components burn rather than recycle. But pyrometallurgy tolerates mixed battery chemistries without sorting, accepts contaminated or damaged cells that hydrometallurgical routes cannot safely handle, and destroys any residual charge. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for legacy waste streams of uncertain composition.

Hydrometallurgical Approaches

Hydrometallurgical approaches dissolve battery materials in aqueous solutions. This chemistry-intensive methodology operates at lower temperatures than smelting, reduces energy consumption, and enables recovery of organic components that pyrometallurgy destroys.

A Rice University study published around 2023 demonstrated that microwave-assisted heating can achieve approximately 87% lithium extraction in just 15 minutes, compared to the 12-hour digestion cycles that conventional processes require. The technology is still scaling up, but the implications for processing times and energy consumption are significant.

Direct Recycling

Direct recycling represents the most intellectually interesting approach, involving complex solid-state chemistry. The basic insight is that cathode powder removed from spent batteries, while depleted of lithium, retains its crystallographic architecture. Direct recycling aims to restore this material through targeted lithium replenishment rather than complete reconstitution.

The relithiation process exposes delithiated cathode powder to lithium sources at elevated temperatures in controlled atmospheres. Lithium ions diffuse into the depleted crystal structure, occupying the sites vacated during battery cycling. Research papers document the effectiveness of this approach, though the reasons why crystal structure survives cycling well enough to be worth relithiating rather than dissolving and remaking require deep materials science expertise to fully explain.

Ames National Laboratory has developed something called BRAWS technology that claims 92.2% lithium extraction using only water and carbon dioxide. If validated at scale, this would eliminate acids entirely. However, laboratory results warrant skepticism until demonstrated at industrial scale, which can take years.

Where the Lithium Actually Sits

The cathode contains 85-90% of recoverable lithium in typical cell designs. Different cathode chemistries distribute lithium at varying concentrations:

| Cathode Chemistry | Chemical Formula | Lithium Content by Mass |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Cobalt Oxide | LiCoO2 | ~7.09% |

| Lithium Iron Phosphate | LiFePO4 | ~4.5% |

| NMC 111 | LiNi0.33Mn0.33Co0.33O2 | ~7% |

| NMC 811 | LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 | ~7.2% |

Lithium cobalt oxide contains approximately 7% lithium by mass. Each formula unit (LiCoO2) incorporates one lithium atom alongside one cobalt and two oxygen atoms. The molecular weights yield a lithium mass fraction of about 7.09%.

Lithium iron phosphate contains roughly 4.5% lithium by mass. The lower concentration reflects the heavier iron and phosphate groups in the LiFePO4 structure.

Nickel-manganese-cobalt cathodes span a composition range depending on the specific ratio. NMC 111 contains approximately 7% lithium, while high-nickel NMC 811 contains about 7.2%.

Liberating pure cathode material is harder than it sounds because everything is stuck together with polymer binders that are difficult to remove.

Graphite anodes contribute 5-10% of total battery lithium through intercalation. During charging, lithium ions migrate from cathode to anode, lodging between carbon layers. The theoretical capacity allows one lithium atom per six carbon atoms (LiC6).

In practice, anodes accumulate additional lithium through plating—metallic lithium deposition on the graphite surface rather than intercalation within it. This plated lithium is bad for battery performance but actually presents recovery opportunities because metallic lithium reacts vigorously with water.

The electrolyte solution carries 3-5% of total cell lithium content. Electrolyte recovery presents both opportunities and hazards. The organic solvents possess significant chemical value, but LiPF6 instability complicates handling. The salt decomposes above 80°C, generating gases that react violently with water. The same hydrogen fluoride concerns apply here.

Separators are simply plastic films. Current collectors are copper and aluminum foils worth recovering for their metal value but not relevant to lithium extraction specifically.

Handling and Disposal

Responsible battery management protects human health and prevents environmental contamination. Based on observed practices at recycling facilities, this bears emphasizing.

Dedicated collection programs provide legal disposal pathways for lithium batteries

Storage conditions matter. Store lithium batteries at room temperature in dry, well-ventilated areas. Elevated temperatures accelerate degradation; storage above 40°C causes measurable degradation within weeks. Conversely, temperatures below freezing can cause electrolyte crystallization. The optimal range is 15-25°C.

Terminal isolation prevents short-circuit hazards. Exposed battery terminals contacting conductive materials can heat cells to ignition temperatures within minutes. Non-conductive electrical tape on terminals eliminates this risk at negligible cost.

Physical damage assessment determines handling pathways. Swollen cells indicate internal gas generation—a precursor to potential venting or thermal runaway. Dented, crushed, or punctured cells may have compromised separators. These damaged cells require immediate segregation and expedited removal by qualified hazardous waste handlers. Under no circumstances should damaged lithium batteries be opened, discharged through external circuits, or disposed through normal waste channels.

Lithium-ion batteries cannot legally enter municipal solid waste or curbside recycling streams in most jurisdictions. The prohibition reflects documented fire incidents at waste handling facilities. Figures suggest over 300 lithium battery fires at recycling facilities between 2018 and 2023, though that is almost certainly an undercount.

Dedicated collection programs provide legal disposal pathways. Call2Recycle operates North America's largest battery stewardship network with over 16,000 drop-off locations. Participation is free for consumers. Similar programs operate in Europe and Japan. Manufacturer take-back programs accept products containing integrated batteries—Apple, Samsung, Dell, HP all provide mail-in recycling with prepaid shipping.

Transportation regulations impose specific requirements. The International Air Transport Association classifies lithium batteries as Class 9 dangerous goods, there are UN-specification packaging requirements, and beginning January 2025 lithium-ion cells should be transported at state of charge not exceeding 30% of rated capacity. For commercial battery shipping, consultation with hazmat transportation specialists is essential.

Selecting qualified recyclers ensures proper handling. Third-party certification programs—R2 and e-Stewards—establish baseline requirements. Certified facilities undergo regular audits. R2 certification requires environmental health and safety management systems and prohibits export to developing countries lacking adequate protections. E-Stewards certification imposes additional requirements including GPS tracking of exported materials.

The Economic Landscape

Scale economies dominate recycling economics. Fixed costs distribute across processing volume. A facility spending $10 million annually on fixed costs while processing 1,000 tons absorbs $10,000 per ton in overhead; the same facility processing 100,000 tons absorbs only $100 per ton. This math is straightforward. Estimates for break-even points for hydrometallurgical operations range from 5,000 to 20,000 annual tons—a wide range reflecting uncertainty in the field.

Battery chemistry determines both lithium content and co-product revenues.

Cobalt-containing chemistries generate substantial revenue from cobalt recovery that effectively subsidizes lithium extraction. A kilogram of spent LiCoO2 cathode contains approximately 600 grams of cobalt worth $15-$21 alongside 70 grams of lithium worth $7-$8.50. Total recoverable value approaches $25 per kilogram before processing costs. The economics work.

Lithium iron phosphate batteries present starkly different economics, which represents a significant concern for the future of battery recycling. LFP cathodes contain no cobalt or nickel—only lithium, iron, and phosphate. Iron sells for approximately $100 per ton; phosphate for perhaps $150 per ton. A kilogram of spent LFP cathode contains approximately $5 in recoverable value. That represents marginal economics requiring either high lithium prices, technological breakthroughs, or regulatory mandates to justify processing.

The market is moving toward LFP batteries for cost and safety reasons. By 2030, LFP batteries may constitute 40-50% of global production, creating massive waste streams with challenging economics. Resolution pathways remain unclear. Perhaps direct recycling technologies mature enough to change the equation. Perhaps regulations mandate recycling regardless of economics. Perhaps lithium prices spike high enough to make it work. Currently, this appears to be a looming problem.

Transportation costs add $100-$300 per ton depending on distance. Chinese recyclers process over 60% of global volume due to accumulated scale advantages.

Resources

For those needing to deal with batteries professionally, the following organizations provide essential guidance:

- Responsible Battery Coalition — Develops best practice guides for battery management

- SERI — Administers the R2 Standard and maintains a directory of certified facilities

- Basel Action Network — Administers e-Stewards certification

- ReCell Center — A DOE collaboration among several national laboratories developing advanced recycling technologies

- EPA — Maintains guidance on handling requirements

- International Energy Agency — Publishes reports on global battery markets

Following academic research from national laboratories reveals promising technologies before commercial deployment. However, caution regarding laboratory breakthroughs is warranted—the gap between "works in a flask" and "works at industrial scale" is enormous, and many promising technologies never make that transition.