A lithium battery stores and releases electrical energy by shuttling lithium ions between two electrodes. That one-sentence definition tells you almost nothing worth knowing.

What matters is why lithium dominates every other battery chemistry so completely that alternatives have become historical footnotes. Lead-acid, invented in 1859, still powers car starters because replacing legacy infrastructure costs money nobody wants to spend. Nickel-metal hydride had a brief moment in 1990s hybrid vehicles before lithium crushed it. Sodium-ion keeps getting announced as "the future" by companies that need something to put in press releases. None of these chemistries threaten lithium's position. They cannot. Physics prevents it.

Lithium sits third on the periodic table. Only hydrogen and helium weigh less, and neither forms stable electrode compounds. Atomic lightness translates directly into energy density: 150-265 watt-hours per kilogram, versus 30-50 for lead-acid. No amount of engineering cleverness closes that gap. You cannot make lead lighter through better manufacturing.

Battery industry conferences feature annual presentations about sodium-ion or zinc-air or flow batteries finally becoming competitive. Attendees nod politely. Everyone knows the presenter needs to justify research funding. Sodium-ion might eventually claim some stationary storage applications where weight penalties are tolerable. Zinc-air works for hearing aids. Flow batteries suit niche industrial uses. None will displace lithium from laptops, phones, electric vehicles, or grid storage at any scale that matters. Presentations end, attendees collect business cards, and lithium manufacturers continue expanding production.

How Lithium Batteries Work

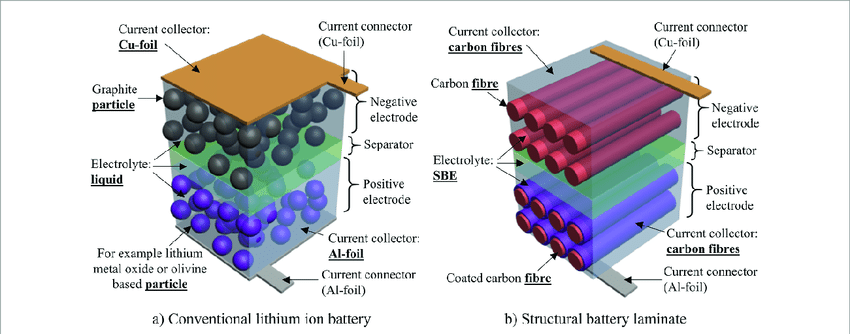

The mechanism is called intercalation, a word that sounds more complicated than the process it describes. Lithium ions wedge themselves into the crystal structure of electrode materials during charging, then migrate back out during discharge. Electrons take a separate path through whatever device draws power. Reversing the process thousands of times without destroying the electrode structures is where the engineering difficulty lies.

Graphite anodes work because carbon atoms arrange themselves in stacked sheets with gaps between them. Lithium ions slip into those gaps. Cathodes use metal oxides with similar accommodation spaces. Separators keep the electrodes from touching while allowing ions through. Electrolyte provides the liquid medium for ion transport. Current collectors channel electrons to external circuits.

None of those components are optional. Separator failure causes thermal runaway within seconds. Electrolyte decomposition creates gas that swells pouch cells until they rupture. Current collector corrosion raises internal resistance until the battery becomes useless. Manufacturing quality control determines whether these failure modes remain theoretical or arrive unexpectedly.

Sony brought the first commercial lithium battery to market in 1991. Research behind it stretched back two decades, with contributions from Whittingham at Exxon, Goodenough at Oxford, and Yoshino at Asahi Kasei. All three shared the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Whether that recognition came too late, given how completely their invention reshaped daily life, is a question the Nobel committee probably prefers not to answer.

Goodenough was 97 years old when the prize was announced. He died in 2023 at 100. His technology now powers devices carried by billions of people who have never heard his name.

Cathode Chemistry Determines Everything

Battery manufacturers do not sell "lithium batteries." They sell lithium cobalt oxide batteries, lithium iron phosphate batteries, lithium nickel manganese cobalt batteries, and several other formulations. Cathode material defines performance characteristics more than any other design choice. Purchasing departments that ignore this distinction waste money.

Cobalt oxide cathodes pack lithium ions densely, producing high energy storage per unit weight. Smartphones and laptops use this chemistry almost exclusively. Cobalt's tendency to release oxygen when overcharged creates fire risk. Cobalt also costs money and comes mostly from mines with documented labor abuses. Consumer electronics companies have decided these problems are acceptable given the energy density benefits and the two-year replacement cycle of most devices.

Supply chain due diligence for cobalt has become a compliance checkbox exercise at most companies. Audit reports certify that specific batches did not involve child labor. Whether those audits reflect reality or just paperwork is difficult to verify. Artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo operates largely outside formal supply chains. Cobalt from those operations enters the market through intermediaries who provide whatever documentation buyers require. Companies that care about actual conditions rather than documentation find the problem nearly intractable.

A battery that exists beats a battery that cannot be manufactured because cobalt prices spiked or shipping routes became unreliable.

Iron phosphate cathodes take the opposite approach. Energy density drops by roughly a quarter compared to cobalt, but thermal stability improves dramatically. Oxygen stays locked in the crystal structure even under abuse conditions. Cycle life extends past three thousand cycles versus maybe eight hundred for cobalt. Chinese battery manufacturers bet heavily on this chemistry starting around 2015, while Western competitors dismissed it as technically inferior. Five years later, Tesla started putting iron phosphate cells in standard-range vehicles. Supply chain calculations had shifted.

Western dismissal of iron phosphate had technical justification that obscured strategic blindness. Lower energy density meant heavier battery packs for equivalent range. Colder temperatures reduced iron phosphate performance more than cobalt alternatives. These disadvantages were real. They mattered less than assumed once supply chain vulnerability entered the calculation. A battery that exists beats a battery that cannot be manufactured because cobalt prices spiked or shipping routes became unreliable.

Nickel manganese cobalt blends split the difference. Adjusting the ratios produces different performance profiles. High-nickel versions approach cobalt's energy density while reducing cobalt content. Balanced formulations trade some capacity for durability. Nickel manganese cobalt blends power most electric vehicles sold in North America and Europe.

Chemists continue optimizing formulations. Papers appear monthly describing incremental improvements. Most never reach production. Laboratory results depend on carefully controlled conditions that factory floors cannot replicate. Promising results at milligram scale often disappear at kilogram scale. Companies that confuse academic publication with commercial readiness invest in technology that never ships.

Transportation Shift

Electric vehicle batteries consumed about two-thirds of global lithium battery production last year. Automotive purchasing power has driven manufacturing scale and cost reductions that benefit every other application.

A decade ago, battery packs cost over $1,000 per kilowatt-hour. Current prices hover around $140. Cost collapse did not happen through breakthrough discoveries. It happened through building more factories, training more workers, optimizing more processes, and accepting lower margins. Boring work of manufacturing improvement outweighed laboratory innovation.

Fleet electrification reveals patterns that individual vehicle sales obscure. Delivery companies track total cost of ownership across hundreds or thousands of vehicles over five to seven year replacement cycles. Their calculations favor different chemistries than consumer marketing suggests. Iron phosphate's longer cycle life and simpler thermal management offset its weight penalty when vehicles make multiple daily trips on predictable routes. Premium energy density matters less when charging infrastructure exists at every depot.

One logistics operator in Southeast Asia switched from lead-acid to lithium starting in 2021. Initial vehicles used nickel manganese cobalt cells based on supplier recommendations. Warranty claims spiked during the second monsoon season. Heat and humidity accelerated degradation faster than projected.

Later orders specified iron phosphate despite the range reduction. Operational data from that fleet now informs purchasing decisions across the industry. Nickel chemistry worked fine in laboratory testing and temperate climates. Tropical deployment exposed assumptions baked into the original specifications.

But the full story is more complicated than chemistry selection. Some nickel-chemistry vehicles from the same batch performed adequately. Others failed. Investigation revealed that vehicles parked in direct sunlight between shifts degraded faster than vehicles parked under covered structures. Driver behavior mattered too. Operators who routinely discharged below twenty percent before recharging saw faster degradation than operators who topped up more frequently. Battery management software from the vehicle manufacturer had parameters optimized for European driving patterns that did not match Southeast Asian usage.

A fleet manager who shared this story added a caveat: iron phosphate vehicles purchased later also showed unexpected variation. Some cells from particular production batches exhibited higher self-discharge rates. Whether this resulted from manufacturing variation, shipping damage, or some other factor remained unclear. Supplier investigation produced inconclusive results and eventually stopped.

Fleet operators rarely publish failure data. Competitive considerations and vendor relationships discourage transparency. Most publicly available information comes from manufacturers promoting their own products. Drawing conclusions from incomplete data is hazardous. Laboratory specifications predict field performance imperfectly. That much is certain.

Grid Storage

Utility-scale batteries operate under completely different constraints than vehicles. Weight is irrelevant. A battery farm can cover acres. What matters is cost per stored kilowatt-hour, cycle life, and calendar aging during the twenty-year expected service life.

Iron phosphate dominates this segment for obvious reasons.

Grid storage runs on arbitrage. Buy electricity when prices are low, sell it when prices are high. Peak pricing in most markets occurs during late afternoon and early evening when solar generation declines but demand remains elevated. A battery that charged during midday sun and discharges during dinner preparation captures that spread.

Revenue projections for these projects depend on pricing differentials that regulators can change. Some early installations in California and Arizona earned their projections. Others struggled when rate structures shifted or wholesale markets saw narrower spreads than forecast. Battery storage investment requires views on both electrochemistry and regulatory policy. Battery technology works. Whether the business case works depends on assumptions external to the battery itself.

Project developers who bet on stable rate structures learned expensive lessons when utility commissions revised tariffs. Installations sized for specific peak/off-peak differentials became marginally economic or unprofitable overnight. Battery technology performed exactly as specified. Financial models built on regulatory assumptions failed.

Fire incidents at grid storage sites have complicated permitting and insurance. A 2021 fire at a utility-scale installation in Australia burned for days and required evacuation of nearby residents. Investigation attributed the failure to a defective battery rack that initiated thermal runaway spreading to adjacent units. Suppression systems designed for the installation failed to contain the fire. Insurance claims and litigation continue years later.

Similar incidents in California, Arizona, and South Korea have raised questions about siting requirements, fire suppression design, and distance from populated areas. Permitting timelines have lengthened. Insurance premiums have increased. These costs rarely appear in project announcements touting battery economics.

That said, stationary storage installations number in the thousands worldwide. Most operate without incident. Fire risk exists but remains statistically rare relative to the installed base. Media attention concentrates on failures while routine operation receives no coverage.

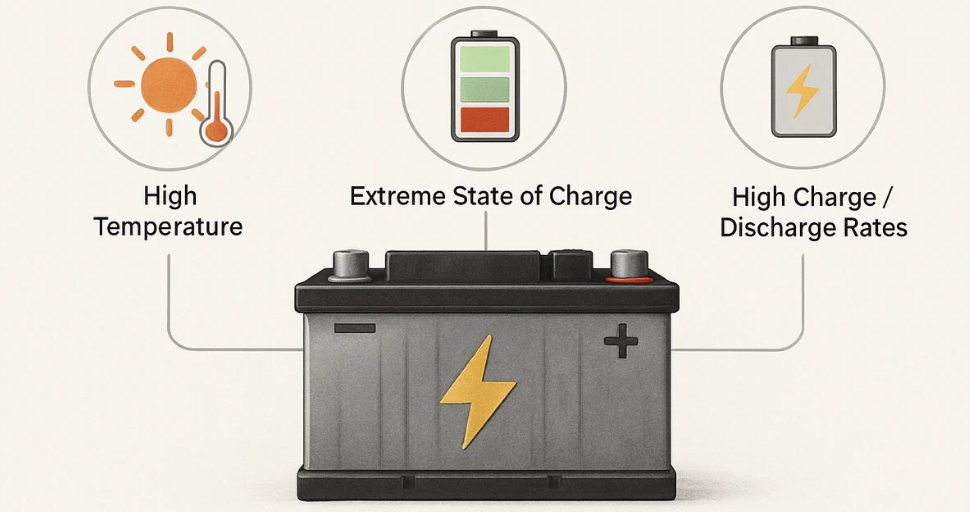

Heat

Heat destroys lithium batteries faster than cycling.

A battery sitting unused at 40°C loses capacity faster than a battery actively used at 20°C. Most people expect wear to happen during use, not during storage.

Parasitic reactions at electrode surfaces cause the damage. Higher temperatures accelerate these reactions regardless of whether the battery is charging, discharging, or resting. Storing a fully charged battery in a hot car for months causes measurable damage. Storing at half charge in climate-controlled space preserves nearly full capacity.

Electric vehicles in Phoenix and Dubai exhibit accelerated battery degradation compared to identical vehicles in Seattle and London. Manufacturers have responded with increasingly aggressive thermal management, running cooling pumps during parking to protect cells from ambient heat. Running cooling during parking consumes energy and adds cost. Buyers in temperate climates subsidize engineering required for extreme environments.

Laptop batteries provide the clearest evidence of temperature effects. Users who keep machines plugged in continuously, with batteries held at full charge and elevated temperatures from adjacent processors, replace batteries far sooner than users who occasionally unplug and allow batteries to cycle in moderate conditions. Service life differences can reach years.

Phone manufacturers have quietly acknowledged the problem. Some recent operating system updates include features that delay charging completion until shortly before typical wake times, reducing hours spent at full charge. Others limit charging to eighty percent when plugged in overnight. These features protect battery longevity at the cost of occasionally delivering less than full charge when users need it. Most users never notice the change or understand its purpose.

Charging Speed Tradeoffs

Fast charging sells vehicles. Marketing departments know that customers worry about long trips and charging station availability. Adding two hundred kilometers of range in twenty minutes addresses those concerns more directly than arguments about home charging convenience.

Electrochemistry is less enthusiastic about rapid charging. High currents generate resistive heating that stresses cell components. More problematically, lithium ions arriving at the anode faster than they can intercalate into graphite can plate out as metallic lithium on the surface. Plating is irreversible. Each fast charge session causes small amounts of plating. Accumulated over years, the capacity loss becomes measurable.

Fleet data from commercial operators shows the effect clearly. Vehicles charging primarily at low power overnight maintain capacity better than vehicles relying on high-power charging during the workday. After 150,000 kilometers, capacity loss approaches twenty percent of original. For individual owners, this degradation might fall within acceptable bounds. For fleet managers replacing hundreds of vehicles on fixed schedules, it changes procurement math.

Charging infrastructure companies have financial incentives that conflict with battery longevity. Companies that own charging stations make money when vehicles plug in. They make more money when vehicles plug in briefly at high power versus slowly at low power because fast chargers cost more to install and can serve more vehicles per hour. Station economics prioritize throughput over battery health. Drivers receive no feedback about degradation costs associated with their charging choices.

Battery Management Complexity

Raw lithium cells are dangerous. Overcharging causes thermal runaway. Over-discharging destroys anode surfaces. Imbalanced cells in series connections drag down pack capacity. Temperature extremes accelerate all degradation modes. Battery management systems address these risks through constant monitoring and intervention.

Voltage sensing on every cell detects overcharge and overdischarge conditions before damage occurs. Temperature sensors identify hot spots that could indicate internal faults. Current measurement enables charge tracking and identifies abnormal loading. Balancing circuits equalize cell voltages within series strings. Contactors disconnect packs from loads when parameters exceed safe bounds.

Consumer-grade implementations cut corners that industrial applications cannot tolerate. A smartphone battery management chip provides adequate protection for a three-year device lifespan. An electric vehicle with a ten-year warranty and 200,000 kilometer expectation requires far more sophisticated protection. Grid storage installations with twenty-year design lives demand industrial-grade monitoring with redundant sensors and fail-safe disconnection.

BMS engineering is invisible to customers but entirely determines reliability. Quality differences between manufacturers appear in warranty claim rates and long-term reliability statistics, not on specification sheets. Procurement departments that evaluate batteries primarily on cell cost miss factors that dominate total ownership expense.

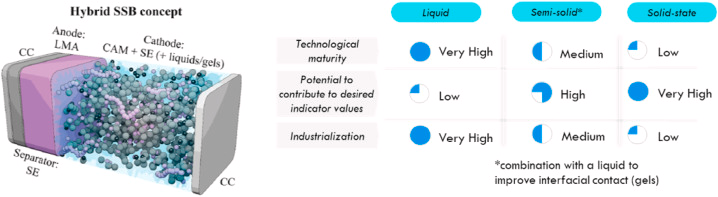

Solid-State Batteries

Since approximately 2015, solid-state batteries have been three to five years away from commercialization. That timeline has not changed despite billions in development spending and countless press releases announcing breakthrough progress.

Theoretical advantages are genuine. Replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid materials eliminates the primary fire risk. Solid electrolytes could potentially stabilize lithium metal anodes, which store ten times more lithium per gram than graphite. Energy densities approaching 500 watt-hours per kilogram become theoretically achievable.

Practical obstacles have proven more stubborn than promoters expected. Solid-solid interfaces exhibit high resistance compared to solid-liquid interfaces. Ceramic electrolytes crack under mechanical stress. Manufacturing processes developed over three decades for liquid cells require complete reinvention. Early production costs far exceed conventional lithium-ion.

Several startups have announced production partnerships with major automakers. None have delivered volume production. Persistent gaps between announcement and delivery suggest that laboratory demonstrations do not translate smoothly to factory floors. Whether solid-state batteries eventually succeed or remain a perpetual future technology is genuinely uncertain. Investment decisions should weight that uncertainty appropriately.

Anyone claiming certainty in either direction is selling something.

Venture capital poured into solid-state battery companies during the 2020-2022 period when electric vehicle enthusiasm peaked. Some of those companies have since reduced headcount or pivoted to less ambitious goals. Others continue burning cash while issuing optimistic press releases. Public company disclosures reveal widening gaps between promised timelines and actual progress. Private companies face less scrutiny but likely similar challenges.

Toyota has worked on solid-state batteries longer than most competitors. Toyota also continues selling gasoline vehicles in volumes that dwarf its electric vehicle sales. Whether Toyota's solid-state program represents genuine technological progress or a strategy to delay electrification while competitors deplete resources remains debated among industry observers. Both interpretations have evidence supporting them.

Honest assessment yields uncertainty. Solid-state batteries might work. They might not. Breakthroughs sometimes happen. They also sometimes don't. Companies and investors betting on solid-state batteries are making a specific technology forecast that could prove correct or incorrect. Anyone claiming certainty in either direction is selling something.

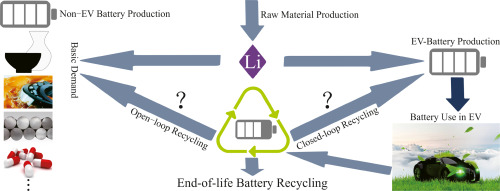

Recycling Remains Underdeveloped

The average lithium battery contains materials worth recovering: lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, aluminum. Current recycling rates remain low because collection infrastructure barely exists and recycling processes struggle to compete economically with virgin material extraction.

Recycling economics will change as the first major wave of electric vehicle batteries reaches end-of-life. Millions of tons of spent batteries will require disposition starting around 2030. Whether recycling capacity scales to match that supply depends on policy decisions and commodity prices that remain unpredictable.

Technical approaches for recycling divide into pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes. High-temperature smelting recovers metals but destroys lithium. Acid leaching can recover lithium but generates waste streams requiring treatment. Neither approach currently operates at the scale that coming battery volumes will require.

Second-life applications extend battery usefulness beyond vehicle retirement. Cells that no longer meet automotive specifications for capacity or power delivery often work adequately for stationary storage applications with less demanding requirements. Grid operators have deployed retired electric vehicle batteries in pilot projects. Whether second-life applications scale beyond pilots depends on standardization, testing protocols, and business models that remain immature.

Complications

Energy density numbers dominate battery marketing despite being one of several factors that determine suitability. Cycle life, calendar aging, thermal management requirements, charging rate tolerance, safety margin, supply chain reliability, and total cost of ownership interact in ways that simple specification comparisons obscure.

Chemistry selection requires understanding application requirements before examining battery options. A warehouse robot, a long-haul truck, a grid storage installation, and a smartphone present radically different optimization problems. Blanket statements about which lithium chemistry is "best" reveal more about the speaker's assumptions than about battery technology.

Most public discussion of batteries focuses on passenger electric vehicles despite that segment representing perhaps a third of lithium demand. Consumer electronics, grid storage, industrial equipment, and commercial vehicles receive less attention but often present more interesting engineering tradeoffs. Passenger vehicles optimize for marketing-friendly specifications like range and charge speed. Other applications optimize for total cost of ownership over long service lives.

Markets continue expanding across nearly every sector that uses electricity. Manufacturing capacity grows faster than demand in some segments, creating temporary oversupply and price pressure. Consolidation will likely reduce the number of major cell manufacturers over the coming decade. Whether that consolidation benefits buyers through scale economies or harms them through reduced competition remains to be seen.

Environmental considerations increasingly constrain design choices. Cobalt mining conditions, nickel processing pollution, and battery disposal regulations all impose costs that specification sheets do not capture. Procurement decisions that ignore these factors face increasing regulatory and reputational risk. Companies that previously avoided environmental questions now employ staff dedicated to supply chain auditing and regulatory compliance. Whether their efforts produce actual improvements or merely documentation remains contested.

Understanding lithium batteries requires accepting that the technology is simultaneously mature and rapidly evolving. Basic electrochemistry has been understood for decades. Applications, manufacturing methods, and integration approaches continue changing faster than most industries can track. Expertise in this domain depreciates quickly. What was true five years ago may no longer apply. What is true today may not hold five years hence.

Anyone claiming complete understanding of lithium battery technology is probably overstating their knowledge. Battery technology moves too fast and covers too many specialties for any individual to master completely. Healthy skepticism toward confident pronouncements applies regardless of whether those pronouncements come from manufacturers, analysts, journalists, or authors of technical articles.