The battery aisle at any major retailer presents alkaline as the default choice. Duracell and Energizer alkaline cells occupy prime shelf space while lithium options sit in smaller sections, often at premium positions or behind glass. A four-pack of alkaline AAs costs $4. The lithium equivalent costs $15. Most shoppers grab the cheaper option, which turns out to be a mistake for most applications beyond wall clocks.

The Capacity Problem

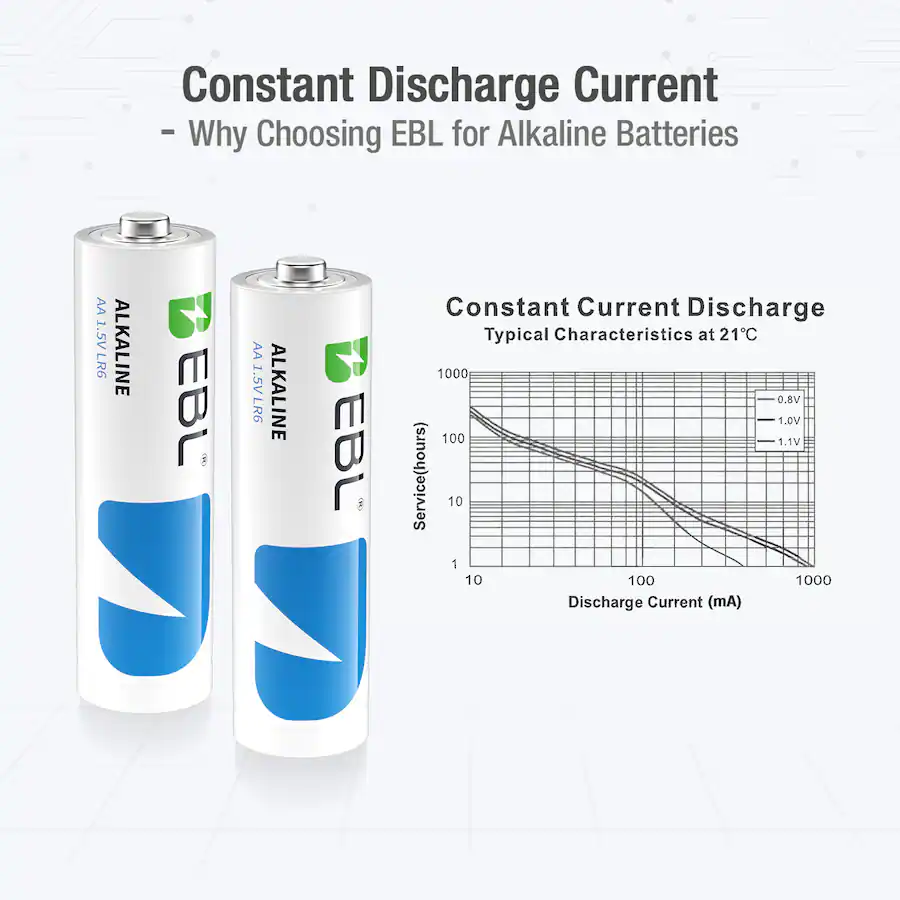

Energizer prints 2800mAh on their MAX alkaline AA. That number comes from testing at 25mA constant discharge, a load so gentle that almost nothing in a typical household actually draws power that way. A wireless mouse might come close.

The discharge curves published in Energizer's E91 datasheet reveal what happens under realistic conditions. At 250mA, the same cell delivers around 1500mAh. At 500mA, below 1000mAh. At 1000mA, below 600mAh. These figures come directly from Energizer's published technical documentation.

Capacity ratings on packaging rarely reflect real-world performance under typical device loads

Zinc oxidation during discharge coats the electrode surface and blocks ion transport, a process called passivation. Fresh cells have internal resistance around 150 to 200 milliohms based on the E91 datasheet specifications, climbing to 500-600 milliohms by half depletion. A device trying to pull 500mA from a half-depleted alkaline cell loses 0.25-0.3V to internal resistance alone. Lithium iron disulfide chemistry avoids this coating problem entirely, maintaining low resistance through most of the discharge cycle.

When alkaline cannot deliver adequate current, autofocus motors stall, flash units refuse to charge, wireless transmitters drop packets. The battery indicator may show 40% charge remaining while the device refuses to function.

Voltage Behavior

Alkaline cells start at 1.5V open circuit and slope downward throughout discharge. Lithium cells hold around 1.7V through most of discharge before dropping sharply near depletion. Four alkaline cells in series deliver 6V when fresh, closer to 4.8V when half depleted. Microprocessors designed for 5V regulation become unstable when input voltage drops too close to output voltage. Displays dim. Wireless range shrinks. Motors lose torque. Flash units take forever to recycle.

Key Insight

Lithium-powered devices work normally until the batteries are nearly dead, then quit abruptly. This sudden cutoff is actually useful because there is no ambiguous middle ground where the device sort of works but not really.

Consumer devices typically trigger low-battery warnings at 1.1V per cell or thereabouts. Alkaline reaches this threshold with 30-40% of its chemical capacity still remaining, inaccessible because voltage has already fallen below what the device requires.

The Broadcast Audio Problem

Between 2010 and 2015, location sound recordists and broadcast engineers largely abandoned alkaline in critical applications. Not because anyone issued a mandate or published a study. Just accumulated frustration after too many ruined takes and too many panicked battery swaps during shoots.

Professional audio production demands reliable power delivery that alkaline chemistry struggles to provide

Wireless microphone transmitters need stable voltage for consistent RF output. As alkaline batteries discharge, transmission power decreases, range shrinks, signal-to-noise ratio degrades, and dropouts become more frequent. A transmitter that worked fine during rehearsal might fail during the actual performance, and nobody can predict exactly when. Entire scenes reshot because a bodypack transmitter decided to drop signal mid-take. Documentary interviews ruined. Wedding vows lost forever. The frustration this caused among production sound mixers is difficult to overstate.

Online forums for production sound professionals from that era, including JW Sound, the Sound Devices user group, and various Facebook communities that have since migrated or disappeared, contain extensive discussions about which lithium cells fit which transmitter models and whether the slightly higher voltage caused any problems. It mostly did not.

Temperature

Avalanche transceiver manufacturers require lithium batteries. Mammut puts this requirement in bold text in their user manuals, with warnings that warranty coverage depends on proper battery selection. An avalanche transceiver that fails because cold-thickened electrolyte cannot deliver adequate current has failed someone who may be buried under snow with limited time remaining.

Extreme cold renders alkaline batteries nearly useless

Summer heat damages batteries through electrolyte evaporation

The chemistry explains why. Alkaline batteries use potassium hydroxide dissolved in water as their electrolyte. Water-based electrolytes get sluggish when cold. At freezing, internal resistance roughly doubles compared to room temperature, and the colder it gets, the worse the problem becomes. The organic solvent electrolytes in lithium cells have freezing points below -50°C. The FAA's Technical Standard Order TSO-C126 for emergency locator transmitters specifies temperature ranges that effectively exclude alkaline chemistry. Search and rescue organizations in cold climates reached the same conclusions independently through operational experience.

Heat causes different damage. Vehicle dashboards reach temperatures exceeding 80°C in summer sun, and above 50°C, water in alkaline electrolyte begins evaporating through the seals. Freeze-thaw cycling causes additional damage. Batteries stored in unheated garages through winter may arrive at room temperature with permanently compromised capacity, and the damage is invisible.

Leakage

Anyone who has worked in electronics repair or vintage electronics restoration would likely endorse this claim: alkaline battery leakage has destroyed more consumer electronics than any other single cause. Electronics repair shops see corroded battery compartments constantly, and vintage electronics collectors consider alkaline damage the single most common form of destruction they encounter.

A battery set costing $3 can destroy electronics worth $150 or $200.

Gas generation during both discharge and storage drives the leakage mechanism. The zinc anode reaction produces hydrogen as a byproduct while the manganese dioxide cathode produces oxygen. Both gases accumulate inside the sealed cell and pressure builds. Cells must vent this pressure or risk violent rupture, so manufacturers design the seals to release gas while retaining liquid electrolyte. The escaped potassium hydroxide, strongly alkaline, reacts aggressively with copper, zinc, aluminum, and solder. Battery terminals corrode first, the damage spreads along any conductive path, and circuit board traces dissolve.

Over-discharge creates the highest leakage risk. When cell voltage drops below 0.8V, zinc corrosion accelerates dramatically. Flashlights left on until they die, toys left running until they stop, remote controls in guest rooms that nobody uses for months.

Battery compartment damage from leakage often costs more to repair than the batteries ever saved

How often do alkaline batteries actually leak? Duracell and Energizer both maintain device damage guarantee programs, which would represent enormous financial liabilities if leakage were rare. Neither company publishes failure frequencies. Understandably so, since doing so would amount to advertising a defect. A battery set costing $3 can destroy electronics worth $150 or $200.

The hermetic seals on lithium cells contain their organic electrolyte far more effectively than the polymer seals used in alkaline construction, and the electrolyte itself does not attack metals even when contact occurs.

Self-Discharge

Alkaline batteries under ideal conditions lose 2-4% capacity annually. Under real-world conditions with summer heat exposure in a garage, warehouse, or delivery truck, losses hit 5-10% per year or more. Batteries purchased off retail shelves have already been sitting in warehouses, distribution centers, and stockrooms for months. Lithium primary cells self-discharge at 1-2% annually with far less temperature sensitivity. A flashlight stored with alkaline batteries for three years may have lost a third of its capacity through self-discharge alone, and if the batteries were already a year old at purchase, the situation worsens.

The Smoke Detector Problem

Fire departments learned about self-discharge through inspection programs. Smoke detector inspections repeatedly found non-functional units despite homeowner assertions of recent battery replacement. People forget. People procrastinate. People hear the low-battery chirp at 3am, remove the battery to stop the noise, and never get around to replacing it. Consumer Product Safety Commission surveys found that 20-30% of installed detectors were operating with depleted or missing batteries, depending on the study and region.

Modern building codes increasingly mandate sealed lithium smoke detectors to address battery compliance failures

Before 2010, smoke detectors universally used replaceable 9V alkaline batteries with annual replacement recommendations. The industry responded to the compliance problem by transitioning to sealed lithium units with 10-year batteries, and building codes in many jurisdictions now mandate sealed lithium smoke detectors in new construction.

High-Drain Devices

Camera users experience alkaline limitations as batteries that suddenly cannot power the flash despite showing 40% charge remaining on the indicator. The photographer presses the shutter, the camera attempts to charge the flash capacitor, voltage sags, and the camera shuts down or displays an error.

Internal resistance determines how much power a battery can deliver regardless of total energy content. The difference between alkaline and lithium seems modest when batteries are new, but as alkaline cells discharge, the gap widens dramatically. Professional speedlights push this limitation to its extreme. Studio and on-camera flash units demand 10-15 amps momentarily during capacitor charging. Fresh alkaline batteries struggle to deliver these currents without excessive voltage drop, and half-depleted alkaline batteries cannot support the load at all.

Professional photography equipment demands consistent high-current delivery that lithium batteries excel at providing

Handheld two-way radios have the same problem. Receive mode draws 50-100mA while transmit mode draws 1-2 amps. Alkaline batteries that handle receive mode adequately may fail during transmit, cutting off communication mid-sentence.

Economics

A four-pack of Duracell Coppertop AA cells sells for $4 to $6 at typical retail. A four-pack of Energizer Ultimate Lithium AA cells costs $12 to $18. But usable capacity under real loads differs by a factor of 2-3x between the two chemistries in high-drain applications. Combined with the price ratio, the cost per delivered milliamp-hour actually favors lithium when devices draw 500mA or more.

Alkaline

- $4-6 per four-pack

- 2800mAh rated (25mA test)

- ~600-1000mAh real-world

- Leakage risk over time

- 2-4% annual self-discharge

Lithium

- $12-18 per four-pack

- 3000mAh rated

- ~2500-3000mAh real-world

- Hermetic seal prevents leakage

- 1-2% annual self-discharge

One leakage incident destroying a device worth $150 or $200 exceeds the lithium price premium that would have accumulated over years of use in that device.

Rechargeable lithium-ion cells extend economic advantages dramatically for applications that consume batteries steadily. Panasonic Eneloop cells cost $4 to $5 each and complete 1500 to 2000 charge cycles per Panasonic's published specifications.

Where Each Chemistry Makes Sense

Wall clocks need nothing that lithium provides. Minimal current draw, climate-controlled environments, alkaline works fine.

Digital cameras present different requirements entirely: high transient current for flash and autofocus motors, extended storage between use sessions creating leakage risk, high device value making leakage damage costly. Remote controls for expensive home theater equipment warrant lithium because the usage pattern means batteries sit installed for extended periods, accumulating leakage risk. The cheap remote that came bundled with a television does not warrant the premium.

Emergency equipment demands lithium without exception—failure at a critical moment could prove catastrophic

Outdoor electronics should use lithium whenever temperatures might reach either extreme. Emergency equipment demands lithium without exception. A flashlight that fails during a nighttime emergency because its alkaline batteries self-discharged or leaked has failed at the worst possible moment.

Medical devices specified lithium before most consumers started thinking about battery chemistry. Glucose meters and hearing aids cannot tolerate the reliability limitations that alkaline chemistry imposes.

Market Position

Alkaline dominates U.S. consumer battery sales despite performing worse than lithium in most applications. Euromonitor and Statista reports from 2022-2023 put alkaline at 70-78% of primary battery retail sales by volume, though the exact figure shifts year to year and varies by how rechargeable batteries are counted.

Price visibility explains most of this. Consumers standing in retail aisles see $4 versus $15 and select the lower number. Retail distribution reinforces alkaline's position. Grocery stores allocate shelf space based on volume and margin, so alkaline occupies checkout aisles, end caps, eye-level shelf positions. Lithium appears in smaller selections, often in specialty electronics areas that casual shoppers never visit.

Capacity ratings on packaging compound consumer confusion: alkaline packaging shows 2800mAh, lithium shows 3000mAh, the numbers appear comparable, and nothing on the package explains that usable capacity under real loads differs by 2-3x. Shoppers who have always bought alkaline continue buying alkaline. Switching to lithium requires a conscious decision to try something different and pay more for it upfront.

Regulatory requirements increasingly mandate lithium for safety-critical applications. Smoke detector standards in many jurisdictions now effectively require sealed lithium units, medical device approvals often specify lithium chemistry, and aviation emergency equipment mandates lithium by FAA technical standard order.

Alkaline technology has reached its limits. Zinc-manganese dioxide chemistry has been refined for sixty years, and the electrochemistry imposes hard ceilings on performance that no manufacturing improvement can overcome. Alkaline will hold market share for years through price advantage and retail distribution momentum, but the underlying technical case favors lithium in most applications where battery performance actually matters.