Nobody in the battery industry wants to admit this: the cells powering an e-bike are fundamentally different animals from the cells in an iPhone, and treating them as members of the same safety category is negligent bordering on dishonest. The phrase "lithium-ion battery" has become a catch-all term obscuring differences so vast that the comparison barely holds. A lithium iron phosphate cell and a high-nickel NMC cell share electrochemical ancestry the way a house cat shares ancestry with a tiger. Puncture one with a nail and it sits inert. Puncture the other and it may burn the garage down.

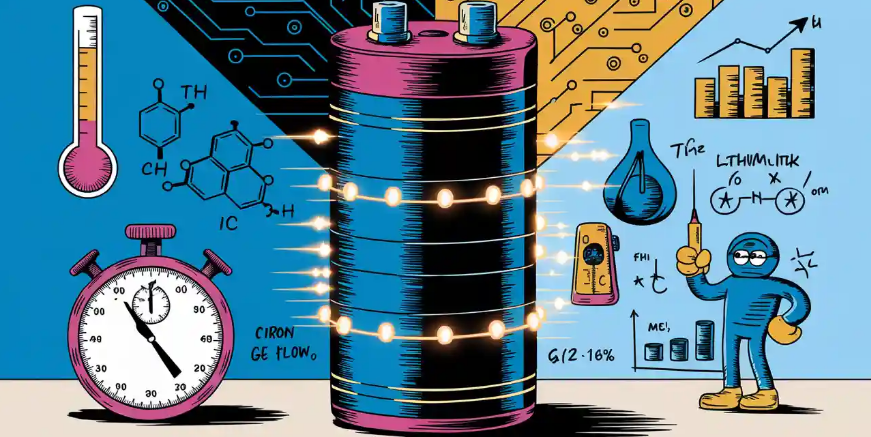

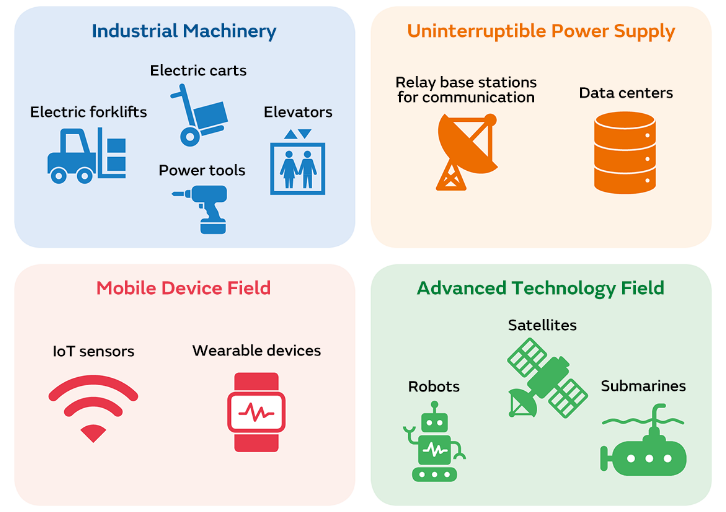

Modern lithium-ion cells power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles, but not all batteries carry the same risk profile.

Massachusetts fire services recorded 97 lithium battery fires over five years ending in 2023. Two percent of those incidents killed someone. Set against hundreds of millions of devices in circulation, 97 fires sounds almost negligible. But this is where statistics become obscene: every one of those fires happened to a specific person in a specific home, and several of those people are now dead. The denominator does not comfort the families in the numerator.

Media coverage oscillates between opposite failures. Local news amplifies every battery fire into evidence of an epidemic, generating fear disproportionate to actual incidence rates. Industry publications minimize every incident as an outlier, implying that statistical rarity means individual consumers need not concern themselves. These framings serve agendas at the expense of useful information. Battery fires are rare enough that panic is unwarranted. They are common enough that complacency is dangerous. They concentrate in specific applications where meaningful risk stratification is possible.

The Chemistry Problem Nobody Discusses Honestly

Most coverage of battery safety treats "lithium-ion" as a single technology with uniform risk. This framing is wrong in ways that matter.

Lithium iron phosphate belongs in a different conversation entirely. The olivine crystal structure creates chemical bonds so stubborn that an LFP cell can reach 270°C before anything interesting happens. Puncture one, overheat one, short-circuit one: the cell will fail, but it will fail politely. No fire. No explosion. Just a dead battery. Tesla figured this out after years of defending their high-performance packs and quietly started shipping LFP cells in their cheaper models. The range takes a 20% hit. The house fire risk drops by something closer to 95%. That trade-off reveals where the industry's priorities actually sit.

The physics behind LFP stability deserves attention because it explains why the safety advantage is not a marginal improvement but a categorical difference. In NMC chemistries, oxygen atoms bond to transition metals in layered structures that become progressively less stable as temperature rises. Past a threshold, the lattice collapses and releases that oxygen directly into the cell interior, where flammable electrolyte vapors are already accumulating. The cell becomes a self-contained incendiary device. LFP avoids this failure mode entirely because its phosphate groups grip their oxygen atoms with covalent bonds that simply do not let go at any temperature the cell could plausibly reach during abuse.

The chemistry inside a battery pack determines its thermal stability and failure characteristics.

Lithium nickel manganese cobalt dominates the market because it tests well on the metrics buyers care about. Energy density charts. Charging speed benchmarks. Range per kilogram. What does not appear on any spec sheet: the thermal runaway threshold sits around 150°C for high-nickel variants, nearly half the temperature margin of LFP. The cathode structure will surrender its oxygen atoms with alarming enthusiasm once that threshold is crossed, and then the situation is no longer a battery fire. It becomes a self-oxidizing chemical reaction that no amount of water will extinguish because the fuel carries its own air supply.

The nickel content in NMC cells has been increasing steadily over the past decade. NMC 111 (equal parts nickel, manganese, cobalt) gave way to NMC 622 and NMC 811, with ever-higher nickel ratios boosting energy density while eroding thermal margins. The marketing emphasizes the gains. The risk accumulates silently until an incident reveals it.

The industry optimized for the wrong thing. Capacity sells. Safety does not, at least not until something burns. Every manufacturer knows this. None will say it publicly because admitting the trade-off exists would invite liability questions nobody wants to answer.

Why Certification Marks Mean Less Than Consumers Think

UL 2054 certification on a battery package means the design passed standardized abuse tests at some point in time. It does not mean the product in the box matches the tested design. It does not mean the manufacturing facility maintained quality standards after certification. It does not mean the cells inside came from the same supplier whose cells passed testing.

This gap has created a business model. Import a battery design that technically passed UL testing three years ago. Source cells from whoever bids lowest this quarter. Assemble in facilities where "quality control" means someone occasionally looks at the production line. Ship with the UL mark prominently displayed. Repeat until something catches fire, then dissolve the LLC and start again under a new name.

Quality control in battery manufacturing varies dramatically between established brands and budget suppliers.

Amazon and Alibaba are flooded with batteries following exactly this playbook. The certification infrastructure cannot keep pace. Regulators test what manufacturers submit, not what manufacturers ship, and the incentive structures reward exactly the kind of corner-cutting that produces fires.

The Battery Management System represents the invisible line between a safe battery and a dangerous one, and almost no consumer understands what a BMS does or how to evaluate whether a battery has a competent one. A proper BMS monitors individual cell voltages, prevents overcharge beyond 4.2V per cell, prevents overdischarge below roughly 2.5V, limits current draw to safe levels, monitors temperature at multiple points, and disconnects the pack if any parameter exceeds safe thresholds. Implementing all these functions properly requires hardware investment and software development. Cheap batteries cut costs by implementing the minimum viable subset: maybe voltage limits, maybe current limits, rarely thorough temperature monitoring, almost never redundant safety pathways.

The difference in protection shows up in the failure statistics. Budget batteries from unknown manufacturers fail at rates orders of magnitude higher than equivalent-capacity packs from established brands, and the price difference between them rarely exceeds 30-40%. The gap represents the cost of a BMS that actually works versus one that exists primarily to check a box on a spec sheet.

Counterfeit cells compound the problem. Panasonic and Samsung and LG manufacture cells that command premium prices because their quality control produces consistent, reliable cells. Gray market operators buy rejected cells from these factories, relabel them as first-quality units, and sell them to battery assemblers who either do not test incoming cells or do not care about the results. A battery pack assembled with counterfeit cells may perform normally for months before the weakest cell fails and takes the pack with it.

Price tells a story. A quality 36V 10Ah e-bike battery contains roughly $150 worth of cells alone, before the BMS, enclosure, wiring, assembly, margin, and shipping. When someone sells that battery for $180, the math does not work unless something has been compromised. The $180 battery is not a bargain. It is a disclosure.

The Charging Problem

Sixty-eight percent of the Massachusetts battery fires traced to charging problems. Not manufacturing defects. Not random failures. Charging.

The charger matters as much as the battery, and the charger market is even less regulated. A lithium-ion cell requires precise voltage termination: charge to 4.2V per cell, no higher, with tight tolerance. A charger that runs 5% high does not charge 5% more. It drives the cell into a stressed state that accelerates degradation, promotes dendrite formation, and increases the probability of thermal events. Cheap chargers from unknown suppliers routinely exceed voltage specifications by margins that would horrify anyone who understood the consequences. The user sees a green light indicating charge complete and assumes everything is fine. The cell has been pushed past its safe limit once again.

Charging practices determine the largest controllable risk factor in lithium battery safety.

Third-party chargers present particular risks. Original equipment chargers are designed for specific battery packs with known characteristics. Replacement chargers sold on Amazon or eBay make broad compatibility claims while cutting corners on voltage regulation, current limiting, and temperature compensation. The savings amount to perhaps $30. The added risk scales with every charge cycle.

Cold charging causes damage that accumulates invisibly. When a lithium cell charges below freezing, lithium ions cannot insert themselves into the graphite anode structure properly. Metallic lithium plates directly onto the anode surface instead, forming microscopic spikes called dendrites. Each cold charge grows the dendrites slightly. Eventually one of them punctures the separator and shorts the cell internally. The battery works fine for months after the damage occurs. Then one day it does not.

The mechanism deserves more attention than it receives. At normal temperatures, lithium ions approach the graphite anode and slip between the carbon layers in a process called intercalation. The graphite expands slightly to accommodate them, and everything proceeds smoothly. Below freezing, the kinetics change. The ions arrive faster than the graphite can accept them. Unable to intercalate, they deposit as metallic lithium on the anode surface. This lithium is not merely misplaced. It is electrochemically active in ways that create problems. The plated lithium consumes electrolyte in side reactions that reduce capacity. It grows as dendrites that eventually bridge the electrode gap. And it does all this without any external indication that anything is wrong.

Winter garage charging is slowly killing thousands of e-bike batteries across the northern United States right now. The owners will not find out until next spring or next summer when the cumulative damage finally manifests as a fire or a violent venting event. There is no warning. There is no symptom. The battery percentage reads normal. The range seems fine. The dendrites grow.

The recommended charging temperature range spans 50°F to 86°F. Above that range, charging still works but accelerates degradation through heat-driven side reactions. Below that range, especially below freezing, charging inflicts damage that cannot be undone. A battery charged ten times at 20°F may have already accumulated enough internal damage to guarantee eventual failure, and its owner has no way to know.

Overnight charging in living spaces puts sleeping occupants at risk during the hours when response time matters most. FDNY data shows 73% of their lithium battery fires involved e-bikes or e-scooters. The majority occurred in apartment hallways and living rooms. Residents charge overnight because that is convenient. Convenience is not a safety strategy.

Thermal Runaway Is Worse Than the Coverage Suggests

A battery fire is not really a fire in the conventional sense. Calling it a fire understates the problem.

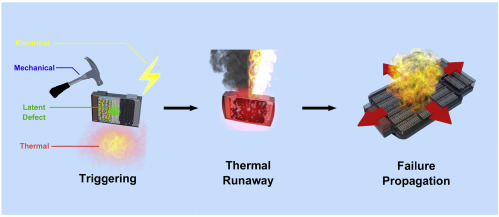

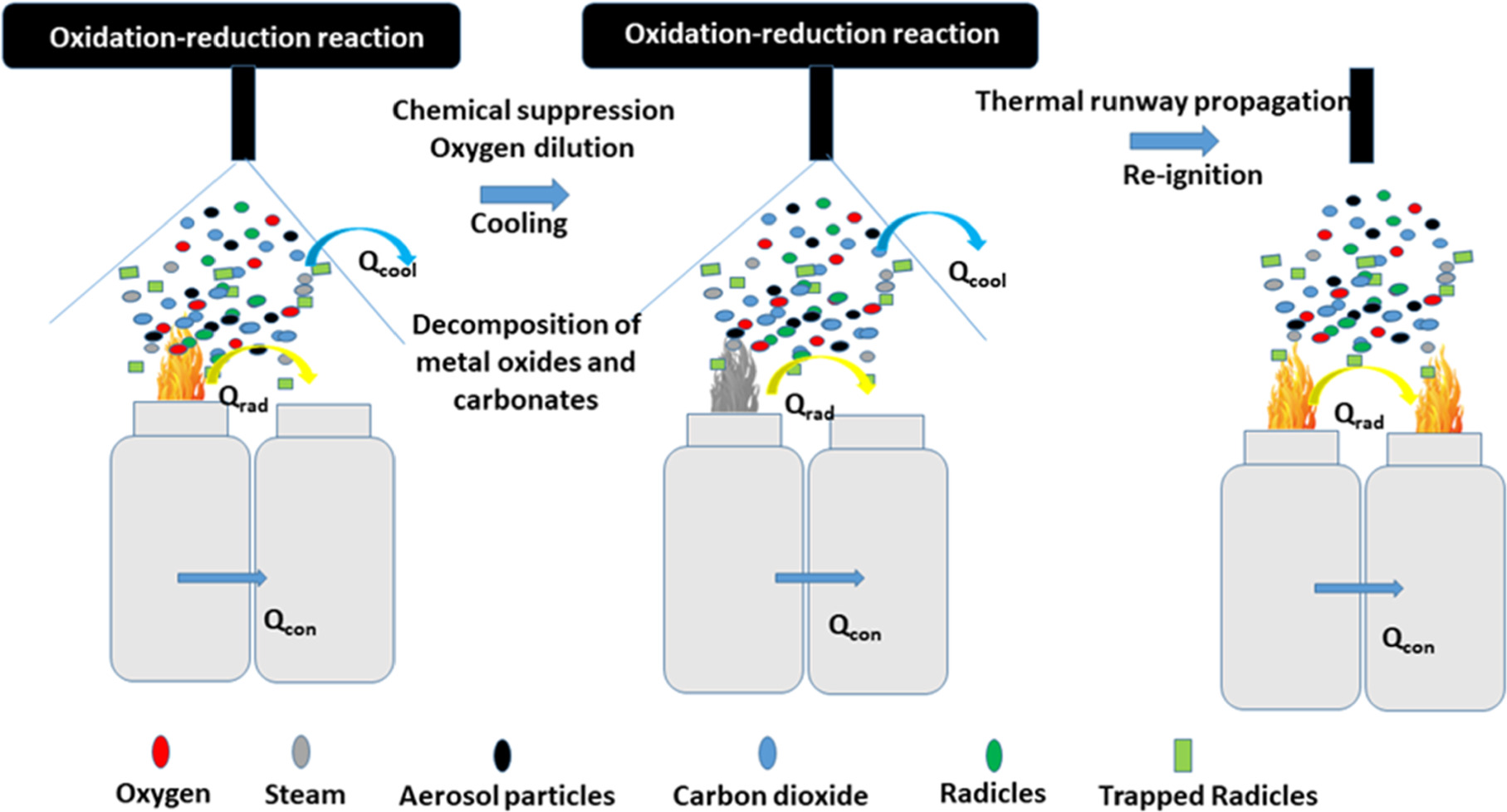

When a lithium cell enters thermal runaway, internal temperature rises past the point where chemical decomposition becomes self-sustaining. The electrolyte breaks down and releases flammable gases. The cathode structure collapses and releases oxygen. Fuel, oxidizer, and ignition source now exist within a sealed metal can. The reaction will continue until the reactants are exhausted. External suppression cannot stop it. Water cannot stop it. Smothering cannot stop it. Cooling the surrounding area and waiting represents the only viable response.

Traditional fire suppression tactics prove ineffective against self-oxidizing electrochemical reactions.

The energy release during thermal runaway is not gradual. A fully charged 18650 cell contains roughly 10-12 Wh of stored energy. During thermal runaway, that energy releases over seconds to minutes rather than the hours a normal discharge would take. The power density of the failure event exceeds the power density of normal operation by factors of 100 or more. A 500Wh e-bike pack entering full thermal runaway releases energy equivalent to a small explosive device, along with a toxic cocktail of fluorine compounds, hydrogen fluoride, and assorted combustion products that make the smoke itself dangerous to breathe.

The human consequences of these fires receive less attention than they deserve. News coverage focuses on the fire itself, shows the charred apartment, quotes the fire marshal, and moves on. The people who lived in that apartment have lost everything. The people who lived in adjacent units may have lost their homes too, through smoke or water damage or structural concerns. Insurance claims take months to resolve. Displacement lasts longer. The psychological effects of waking to flames in the hallway where a child walks every morning persist longer still.

Multi-cell packs make the thermal runaway problem worse. Heat from one failing cell conducts to adjacent cells. Those cells reach their thermal threshold and enter runaway themselves. The cascade propagates through the pack. A single-cell failure in a smartphone is a nuisance. A cascading failure in a 500Wh e-bike pack is a structural fire. Pack design can slow cascading through thermal barriers and spacing between cells, but these measures add weight and cost. Budget battery manufacturers skip them.

Fire departments have not fully adapted. Traditional fire suppression training assumes oxygen can be cut off or heat removed faster than the reaction produces it. These approaches fail against a self-oxidizing electrochemical reaction. Some departments have adopted specialized protocols involving massive water application over extended periods. Many have not. First responders arriving at a lithium battery fire may attempt standard suppression tactics that prove ineffective, losing critical minutes while the fire spreads to surrounding structures.

The water requirements stagger firefighters accustomed to conventional structural fires. A Tesla Model S fire in 2024 required 3,000 gallons over four hours. The cells keep producing heat until the reactants are exhausted, and cooling them below their thermal threshold requires sustained water application that standard apparatus may not support. Departments in areas with high e-bike density are learning this. Departments elsewhere will learn it when their first lithium fire teaches them.

The E-Bike Situation Is Bad and Getting Worse

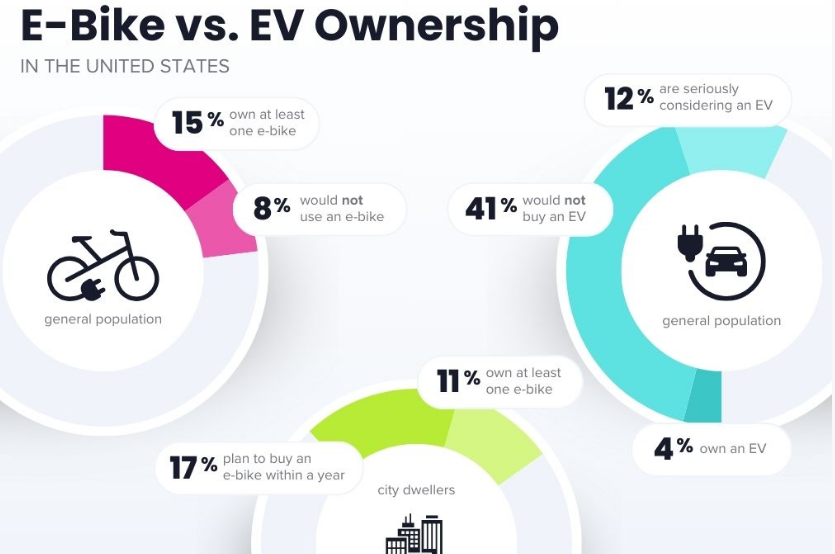

New York City recorded 268 lithium battery fires in 2023. E-bikes and e-scooters accounted for roughly three-quarters of them. The concentration is not coincidental.

E-bikes sit at the intersection of every risk factor simultaneously. High energy density packs. Daily charge cycles accelerating wear. Exposure to rain, impacts, temperature swings, vibration. A customer base that purchases primarily on price. Suppliers operating through dropshipping arrangements that make accountability impossible to establish. Minimal regulatory oversight. The product category is a case study in how market structures can amplify inherent technology risks into actual harm.

E-bikes combine high energy density, daily charging cycles, and a price-sensitive customer base into a concentrated risk profile.

The growth trajectory makes the problem worse each year. E-bike sales in the United States roughly doubled between 2020 and 2023. The infrastructure to support safe e-bike use did not double. The regulatory capacity to monitor e-bike battery quality did not double. The consumer education about e-bike battery safety barely exists. Into this gap flows an ever-increasing volume of cheap batteries from manufacturers who prioritize price over safety and who face no meaningful accountability when their products fail.

Delivery workers face the sharpest version of this problem. The economics of gig delivery push toward cheap equipment, maximum utilization, and minimal downtime. Charging fast, charging often, charging in whatever space is available. The workers absorb the safety risks while the platforms and restaurants capture the value. A delivery worker whose e-bike catches fire in their apartment building faces consequences the algorithm does not. The gig economy has externalized battery fire risk onto the workers least able to bear it and the neighbors least responsible for creating it.

The secondary battery market adds another layer of risk. Delivery workers and budget-conscious commuters often buy used batteries or aftermarket replacements when their original packs degrade. These secondary market batteries come with unknown usage histories, unknown storage conditions, and unknown charging histories. A battery that spent two winters charging in an unheated garage may have accumulated enough dendrite damage to fail catastrophically, and nothing about its external appearance indicates this. The buyer has no way to assess the risk. The seller may not even know the risk exists.

Refurbished batteries present similar problems with a veneer of legitimacy. Refurbishment typically means replacing visibly damaged cells while retaining cells that appear functional. The retained cells carry their accumulated wear, their degraded separators, their microscopic damage. A refurbished pack is not a new pack. It is a used pack with some new parts, sold at a price point that attracts exactly the buyers least able to absorb the consequences of failure.

Building managers in dense urban areas have started banning e-bike charging in common areas and sometimes in units entirely. The bans are blunt instruments addressing a real problem. They also push charging into even less appropriate spaces: storage closets, stairwells, anywhere residents think enforcement will not reach. The underlying risk does not disappear. It redistributes into harder-to-monitor locations.

Some buildings have installed dedicated e-bike charging rooms with fire suppression systems and ventilation. The approach makes sense but requires capital investment that most building owners resist. The math is straightforward: fire suppression systems cost money upfront and eliminate a diffuse, probabilistic risk. Building owners who think in terms of quarterly returns rather than long-term liability exposure will not make that investment unless regulation compels them. Regulation has not yet caught up.

What Actually Reduces Risk

Battery chemistry selection matters more than anything else on this list, and consumers have almost no visibility into it. Spec sheets list capacity and voltage. They rarely list cathode chemistry. LFP packs exist for e-bikes and cost 30-40% more than their NMC equivalents at similar capacity. That premium buys a thermal stability margin worth having. But the premium only makes sense if buyers know enough to ask for it, and most do not.

Asking directly sometimes works. Reputable manufacturers will disclose cathode chemistry on request. The willingness to answer the question itself signals something about the manufacturer. Companies confident in their product quality tend to share information freely. Companies hiding behind vague spec sheets tend to have reasons for the vagueness.

Established brands invest in quality control systems that budget manufacturers skip entirely.

Brand selection filters out the worst offenders not because established brands are inherently virtuous but because they have accumulated reputational capital that constrains behavior. Samsung ate billions in losses over the Note 7 recall and emerged with battery testing protocols that exceed industry standards. The incentive structure worked. Fly-by-night importers face no equivalent constraint. They have no reputation to protect and no continuity of legal identity to sue.

The brand filter is not perfect. Established brands occasionally produce defective batches. The Hyundai Kona EV recall demonstrated that even major automakers with extensive quality systems can ship problematic batteries at scale when supply chain failures occur. But the failure rate for established brands remains orders of magnitude below the failure rate for unknown manufacturers. The correlation between brand recognition and battery quality reflects real underlying differences in manufacturing practice, not mere marketing.

Charging discipline addresses the largest single risk factor and costs nothing. Room temperature charging. Observation during charging. Never overnight in occupied spaces. Never below freezing. Disconnect when complete. These behaviors sound tedious. They also account for most of the difference between the 0.001% incident rate for personal electronics and the much higher rates for e-micromobility devices.

Physical inspection catches damage before it becomes failure. Swelling is the obvious sign, but impact damage matters too. A battery dropped from height may look fine externally while harboring internal damage that will manifest later as thermal runaway. Any battery that has taken a serious impact warrants retirement regardless of how it performs afterward.

Storage conditions matter more than most users realize. Batteries stored at high temperatures degrade faster than batteries stored cool. Batteries stored fully charged degrade faster than batteries stored at partial charge. A battery left in a hot car for months while its owner travels may emerge functionally intact but with accelerated aging that increases failure risk over subsequent use. The damage is invisible. The risk is real.

The Disposal Problem

Lithium batteries do not belong in household trash. They cause fires at waste processing facilities with disturbing regularity. The recycling infrastructure exists. It recovers 95% of materials. Collection points operate at most major retailers. The barrier to proper disposal has dropped to near zero.

The gap between availability and adoption reflects consumer education failure more than infrastructure failure. People discard lithium batteries improperly because they do not know improper disposal is a problem. The resulting facility fires make local news and then fade from attention. The pattern continues.

Where This Leaves Consumers

The situation is not hopeless but it is not good. Lithium battery technology powers the devices and vehicles that modern life increasingly requires. The benefits are real. The risks are also real and concentrate in specific applications where market structures have failed to price safety appropriately.

The e-bike purchased on price from an untraceable brand, charged in the hallway, never inspected, occupies a different risk category than the smartphone from an established manufacturer used with its factory charger. The statistics aggregate across these scenarios. Individual outcomes depend heavily on which scenario applies.

The benefits of lithium battery technology are real, but so are the concentrated risks in specific applications.

The information asymmetry between manufacturers and consumers remains the core problem. Battery chemistry affects safety by factors of five or more, but chemistry rarely appears on packaging. BMS quality determines whether a thermal event becomes a contained failure or a cascading fire, but consumers have no way to evaluate BMS implementation. Cell origin and quality control practices matter enormously, but the supply chain obscures them. Consumers are asked to make safety-critical purchasing decisions without access to safety-critical information.

Regulation will eventually catch up. The pace of regulatory adaptation moves slowly while the pace of deployment accelerates. New York City passed e-bike battery legislation in 2023. Enforcement remains inconsistent. National standards remain nonexistent. European regulators have moved faster, but the same batteries that fail EU certification sell freely in American markets with no disclosure required.

The industry could solve this problem but has chosen not to. Battery chemistry could be required on packaging. BMS functionality could be standardized and verified. Cell sourcing could be documented and auditable. These measures would add cost. They would also prevent fires. The industry has decided that preventing fires is less important than maintaining price competitiveness against manufacturers who will not voluntarily adopt safety measures. This calculation makes business sense right up until it does not.

Until regulation catches up or the industry chooses differently, the burden of risk assessment sits with consumers who lack the information needed to make informed decisions. The battery industry has not provided that information because providing it would require admitting trade-offs exist. This article exists because someone should.