This gap in understanding produces real consequences. Firefighters are increasingly recognizing lithium battery incidents as a distinct hazard category.

The whole thing comes down to what's happening at the atomic level. Some lithium chemistries permit ions to shuttle between electrodes indefinitely, their crystalline structures flexing with each cycle. Others are one-and-done. The chemical reaction runs one way and that's it.

Can You Recharge All Lithium Batteries?

Short answer: no.

The lithium battery category splits into two fundamentally different branches: secondary cells (the rechargeable ones) and primary cells (use once, then recycle or trash). The engineering is completely different.

Rechargeable lithium batteries work through something called intercalation. Lithium ions wedge themselves into layered electrode materials, and the structure holds up. The process can be reversed later.

Modern lithium battery technology enables countless portable devices

The main players in rechargeable are Lithium-Ion, Lithium Polymer, and Lithium Iron Phosphate. Li-ion is what's in phones, laptops, and EVs—lithium ions moving between graphite on one side and metal oxide on the other. Consumer devices typically get 300-500 cycles, though some high-end cells are marketed at 3,000+ cycles. Whether they actually deliver that in real-world conditions is another matter. LiPo swaps the liquid electrolyte for a polymer, which lets manufacturers make unusual shapes—drone enthusiasts know these well. LiFePO4 is the reliable option with lower energy density but robust chemistry resistant to thermal runaway.

Non-rechargeable lithium batteries are a different category entirely. They use metallic lithium, the lightest and most energetic option, but it's a one-way street. Lithium Manganese Dioxide powers those CR2032 coin cells in car key fobs—three volts, dead flat discharge curve, lasts forever on a shelf. Probably the most common primary lithium chemistry. Lithium Thionyl Chloride shows up in industrial applications like utility meters and military gear, applications where a battery needs to sit for a decade and then work perfectly. Chlorine gas is involved in recharge attempts. These should not be recharged. Lithium Iron Disulfide is what Energizer Ultimate Lithium uses—premium AA replacements that maintain voltage better than alkaline.

Market-wise, rechargeable technology dominates by a huge margin. BloombergNEF's 2024 report put global lithium-ion production at approximately 2 terawatt-hours capacity, dwarfing primary battery markets. Yet primaries persist where they make sense.

The chemical difference at the core: rechargeable batteries store lithium in carbon structures that stay intact. Primary batteries literally consume their metallic lithium anode. It's gone when it's gone.

Lithium vs. Lithium-Ion: The Rechargeability Difference

Both battery types contain lithium. Only one can be recharged. The similar naming is confusing.

The Metallic Lithium Problem

Primary lithium batteries use lithium metal because it's electrochemically spectacular—highest voltage potential of any element. But attempting to charge it causes problems.

When current is forced into a lithium metal electrode, lithium ions plate out as metal on the surface. They don't plate evenly though. Branching structures called dendrites form. These spiky structures reach across toward the other electrode and eventually puncture the separator.

Internal short circuit follows. Localized heating spirals out of control. Cells can hit 600°C in seconds—a figure documented in Sandia National Labs thermal runaway studies.

Graphite anodes solve this problem. That's why rechargeable batteries use them instead of pure lithium metal. The trade-off is significant energy density—graphite holds maybe a tenth of what pure lithium could theoretically store—but without the dendrite nightmare.

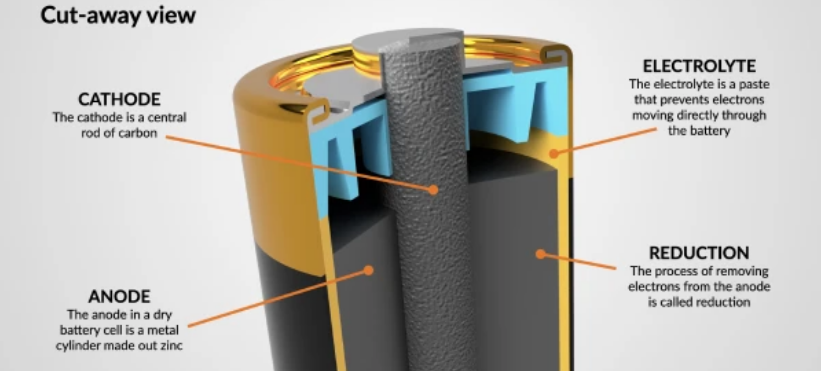

Why the Internal Design Is So Different

Rechargeable batteries have separators with ceramic coatings, carefully formulated electrolytes with additives that form protective layers, engineered current collectors. Everything is designed to survive thousands of cycles.

Primary batteries lack these features. Why engineer for cycle 2 when there won't be one? They optimize for maximum energy extraction from a single discharge. Different goals, different engineering.

The Numbers Game

A lithium thionyl chloride cell can exceed 500 Wh/kg. Best lithium-ion cells are around 250-270 Wh/kg. So primaries win on energy density.

Self-discharge is dramatically different too. A good primary lithium cell retains 90% after a decade. Lithium-ion loses a few percent monthly. For emergency equipment, that matters.

Temperature range is another advantage for primaries. Li-SOCl2 works at -55°C. Charging a lithium-ion battery below freezing causes problems. The batteries designed for extreme cold are mostly used in applications like arctic research stations and military equipment—places where the math still favors primaries.

So When Do You Actually Save Money Going Rechargeable?

A $3 coin cell in a key fob lasting three years is hard to beat economically. A $20 rechargeable setup makes sense only with hundreds of cycles.

Battery prices have been falling, especially for Li-ion. The gap between rechargeable and primary economics keeps widening for high-use applications.

Why Some Lithium Batteries Cannot Be Recharged

This isn't a suggestion or a warranty issue. It's physics.

The dendrite problem is worse than commonly understood. Those metallic structures grow at micrometers per minute under charging current. A typical CR2032 separator is approximately 20-25 micrometers thick. Minutes to hours before penetration.

Then there's electrolyte incompatibility—completely separate issue. Li-SOCl2 cells use thionyl chloride as both cathode and electrolyte. Electrolyzing that produces chlorine gas and sulfur dioxide. These are not chemicals that should vent in a home.

The discharge products of primary batteries are thermodynamically stable endpoints. The reaction has already gone "downhill" energetically speaking. Getting back up would take more energy than would be recovered. The chemistry is specifically designed to be irreversible.

Understanding battery chemistry prevents dangerous mistakes

How Rechargeable Lithium Batteries Actually Work

A lithium-ion battery functions as a lithium pump. Charge it: lithium moves one direction. Discharge it: lithium flows back. Repeat.

The Graphite Anode

Graphite structure consists of stacked sheets with gaps between them—around 0.34 nanometers, per standard crystallography references. During charging, lithium ions squeeze into those gaps and the structure swells about 10%. Electrode engineers must account for that expansion with special binders and controlled porosity, otherwise cracking occurs. There's been a lot of research into silicon anodes because silicon can hold more lithium, but the swelling problem is brutal—approximately 300% expansion. Some companies have made progress with silicon-graphite composites, mixing in just enough silicon to boost capacity without destroying the electrode mechanically. The whole field is basically an ongoing battle against physics.

Fully loaded graphite contains about one lithium atom per six carbons. Attempting to add more causes damage.

Lithium cobalt oxide was the original cathode chemistry from Sony in 1991, NMC is what most EVs use now, and there's a whole range of variants. They all have limits on how much lithium can be extracted before the crystal structure falls apart. That's why voltage limits matter.

What the Battery Management System Actually Does

Modern lithium-ion packs have a computer monitoring them constantly. Voltage monitoring on every cell, typically around 10 millivolts resolution—enough to catch cells drifting toward failure. Current limiting to prevent resistive heating from getting out of control. Temperature monitoring that blocks charging below freezing and reduces current when things get hot. Cell balancing to keep series cells from getting out of sync. State of charge estimation, though these algorithms can be inaccurate depending on the implementation.

Charging phases follow a standard protocol: a pre-charge phase at reduced current for deeply depleted cells, then constant current until approaching full voltage, finally constant voltage while current tapers off. Termination happens when current drops below a threshold.

The voltage precision required is tight. Approximately 50 millivolts deviation can cause problems—either accelerated degradation or unused capacity.

Telling Them Apart

Rechargeable Indicators

Usually labeled "Rechargeable" somewhere on the battery, along with chemistry codes like Li-ion, Li-Po, or LiFePO4.

Capacity listed in mAh with voltage (like "3,400 mAh 3.7V") and sometimes cycle life claims.

Non-Rechargeable Indicators

Often just labeled "Lithium" without "ion," and include warnings like "Do Not Recharge."

Use codes starting with CR, BR, or ER, and typically show just voltage without capacity ("3V").

There's an IEC system for the codes. Quick version: if the code starts with "I" (ICR, INR, IFR), it's intercalation chemistry—rechargeable. No "I" prefix (CR, BR, ER) means primary.

Physical Formats

Cylindrical cells with numbers like 18650 or 21700 are almost always rechargeable lithium-ion. The numbers are dimensions in millimeters.

Coin cells are trickier. CR2032 is non-rechargeable. LIR2032 is rechargeable. That first letter matters.

Best Practices for Rechargeable Lithium Battery Use

Charging Tips

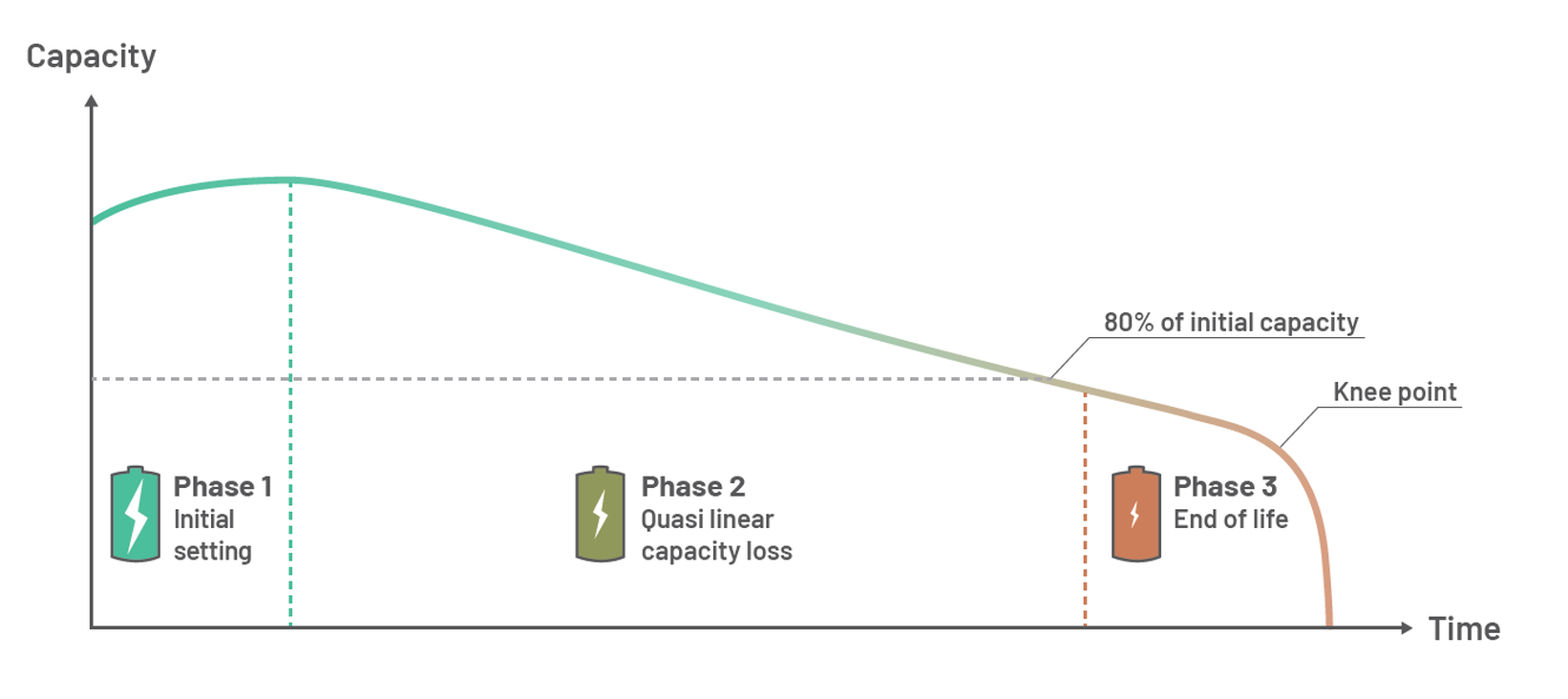

Keep batteries between 20-80% when possible. Both fully charged and fully depleted states stress the electrodes. Laptops kept plugged in continuously age their batteries faster than necessary.

Don't discharge to zero. Below about 2 volts, the copper current collector starts dissolving. It redeposits as dendrites during the next charge. Most management systems cut off around 2.5-3V to prevent this.

Fast charging is acceptable occasionally but shouldn't be the default. The I²R heating adds up over time.

Temperature

Hot is bad. A battery running at 45°C ages roughly twice as fast as one at 25°C—this relationship is well documented in the literature, including work from Jeff Dahn's lab at Dalhousie. Every 10 degrees matters.

Cold is also problematic, but differently. Charging below 0°C causes lithium plating—permanently damaging. Most systems lock out charging when cold. Discharging in the cold is mostly acceptable, just with temporarily reduced capacity.

For storage, 40-60% charge is optimal. Keep batteries cool and dry.

Proper care extends battery lifespan significantly

Selecting the Right Battery Type

When Rechargeable Makes Sense

High-drain devices used frequently. The economics work out fast—8-10 cycles and the break-even point versus disposables is reached.

Environmental considerations apply too, though lifecycle analyses are complicated and depend heavily on assumptions.

When Primary Makes Sense

Emergency gear. A flashlight in an earthquake kit needs to work after sitting for years. Rechargeable batteries require maintenance; primaries just wait.

Low-drain applications where cycling is infrequent. Smoke detectors. Remote controls. A rechargeable battery would degrade from age before being cycled enough to justify the cost.

Extreme environments. That -55°C rating on lithium thionyl chloride isn't marketing—it actually works. Finding a lithium-ion cell that charges at those temperatures is difficult.

Remote installations. If sending someone to change batteries costs $500, the longest-lasting option is preferable regardless of unit price.

Most people should have both. Rechargeables for daily-use items—flashlights, game controllers, frequently cycled devices. Primaries for emergency gear, smoke detectors, and items that will be forgotten for years. Match the technology to the application.

Solid-state batteries are a separate topic and the technology isn't mature yet despite press releases.

Frequently Asked Questions

Charging something labeled non-rechargeable

Don't attempt it. Metallic lithium forms dendrites that short the cell internally. This happens faster than commonly expected.

If a primary cell was accidentally charged

Best case is the charger refuses or the cell vents and dies. Worst case is thermal runaway and fire. If swelling, heat, or strange smells are noticed, get the cell outside immediately. Don't use water on lithium fires.

Voltage compatibility when swapping alkalines for lithium

This causes problems. Standard lithium-ion runs 3.6-3.7 volts, much higher than the 1.5V alkalines produce. Some lithium cells have built-in regulation to output 1.5V—those work as drop-ins. Without that regulation, the powered device will likely be damaged.