Can 48 Volt Lithium Battery Handle Load?

Yes. Longer answer: it depends on which battery, and most spec sheets lie by omission.

The 48V lithium market is a mess. Fifteen years ago, buying a battery meant choosing between three or four established brands with predictable quality. Now there are hundreds of manufacturers, most of them assembling cells from the same handful of Chinese suppliers, slapping on their own BMS, and printing whatever specs sound competitive. A 100A continuous discharge rating might mean the battery can sustain 100A in a 25C lab with perfect airflow for an hour. Or it might mean the marketing department picked a round number.

The BMS Problem

Every 48V lithium pack has a Battery Management System. The BMS monitors cell voltages, controls charging, handles balancing, and for load handling purposes, limits discharge current. When people ask whether a 48V battery can handle their load, the answer almost always comes down to BMS capability, not cell capability.

Here is what happens in a typical budget battery: the manufacturer sources decent cells, maybe EVE or CATL B-grade stock, perfectly adequate for 1C discharge. They need a 100A BMS to match. Good 100A BMS boards cost $80-120. Cheap ones cost $25-40. Guess which one goes into a battery selling for $400 retail.

The cheap BMS uses MOSFETs rated for 100A at 25C on a heatsink with forced airflow. But the BMS sits inside a sealed battery case with no airflow at all. Ambient temperature inside the case during discharge can hit 45C easily. At that temperature, those same MOSFETs might only handle 60-70A before thermal derating kicks in. The spec sheet still says 100A because technically the MOSFETs are 100A parts.

Pull 80A from this battery and after twenty minutes the BMS temperature rises, internal resistance of the MOSFETs increases, voltage sag gets worse, and eventually the thermal protection triggers. The battery shuts down. User thinks they got a defective unit. They did not. The battery performed exactly as designed. The design just was not honest about its limits.

This explains roughly 80 percent of the complaints on RV and solar forums about batteries that cannot handle the rated load. Not bad cells. Not manufacturing defects. BMS thermal limits that nobody mentioned.

The MOSFET issue goes deeper than simple thermal derating. MOSFETs have an Rds(on) specification, the resistance when fully conducting. This resistance generates heat proportional to current squared. A MOSFET with 2 milliohm Rds(on) dissipates 20 watts at 100A. Six MOSFETs in parallel (common in 100A BMS designs) each carrying 17A dissipate about 3.5 watts total. But if thermal conditions force two MOSFETs offline, the remaining four now carry 25A each, dissipating over 6 watts. The thermal situation compounds itself.

Budget BMS boards sometimes use MOSFETs from unknown suppliers with Rds(on) values 50-100 percent higher than name brand parts. The BMS still passes bench tests at room temperature. In the field, those extra milliohms matter.

The fix is straightforward but expensive: better MOSFETs, better thermal interface materials, sometimes active cooling. Overkill Solar BMS boards cost three or four times more than generic alternatives partly because they use oversized MOSFETs and aluminum backplates. Whether that premium is worth it depends on the application.

One way to spot this issue before buying: ask the manufacturer for BMS derating curves at elevated temperatures. Reputable companies will have this data. Budget brands will not know what you are talking about. Another approach: ask what happens at 100A continuous for one hour in a 35C environment. Silence or deflection tells you everything.

Why Cell Specs Do Not Tell the Whole Story

LiFePO4 cells from major manufacturers handle 1C continuous discharge without drama. This is well established. A 100Ah cell can sustain 100A. CATL, BYD, EVE, Gotion all publish this in their cell-level datasheets.

But cell-level specs do not translate directly to pack-level performance. A 16S pack has 15 cell-to-cell connections, two terminal connections, internal bus bars, and the BMS current path. Each connection point adds resistance. Each resistance point generates heat under load. A cell rated for 1C at 25C might be sitting in a pack that reaches 40C internally after thirty minutes of discharge, changing the math entirely.

Pack internal resistance varies wildly by assembly quality. Spot welded connections vs bolted connections. Nickel strips vs copper bus bars. Wire gauge to the terminals. These details do not show up on spec sheets. Two batteries with identical cell specs can have 30-40 percent different pack resistance depending on construction choices.

The practical consequence: a 100Ah battery from manufacturer A delivers stable voltage under 80A load for an hour. The same capacity battery from manufacturer B, using the same cells, shows significant voltage sag at 60A and triggers BMS protection at 75A. Same cells. Different pack engineering.

Asking manufacturers about pack-level internal resistance (not cell resistance) sometimes reveals useful information. Anything under 40 milliohms for a 48V 100Ah pack is decent. Under 30 milliohms is good. Most budget packs run 50-70 milliohms, which explains their real-world limitations.

The cell grade issue compounds this. A-grade cells from CATL or EVE have tightly controlled capacity and resistance. Every cell in a batch matches within a few percent. B-grade cells failed some specification during quality control. Maybe capacity came in at 98Ah instead of 100Ah. Maybe internal resistance measured 5 percent high. Maybe the cell passed electrical tests but had cosmetic defects.

B-grade cells work fine individually. The problem is matching. A pack built from A-grade cells has uniform characteristics throughout. The BMS balances easily because cells behave identically. A pack built from B-grade cells might have one cell at 97Ah, another at 103Ah, a third with noticeably higher resistance. During discharge, the weak cell hits low voltage cutoff first, limiting pack capacity to whatever that cell can deliver. During charging, the strong cell hits full voltage first, leaving the others undercharged. The BMS tries to balance, but if the mismatch exceeds the balancing current capacity, the pack drifts further out of balance over time.

Budget batteries almost universally use B-grade cells. The cost savings are substantial, maybe $50-100 per pack at the 100Ah size. Nothing wrong with this if the pack-level testing catches mismatches and rejects problematic combinations. Whether that testing actually happens at any given manufacturer is anyone's guess.

Connection quality inside the pack creates another variable nobody talks about. Some manufacturers laser weld bus bars to cell terminals. Some use resistance spot welding. Some bolt everything together. Each method has different contact resistance, different long-term reliability, different failure modes.

Laser welding makes the best joints but requires expensive equipment. Spot welding is cheaper and works fine if done correctly. Bolted connections depend heavily on torque and washer quality. Over time, bolted connections can loosen from thermal cycling, increasing resistance at exactly the points carrying the most current. This shows up as increased pack internal resistance months or years after purchase, often blamed on cell degradation when the cells themselves are fine.

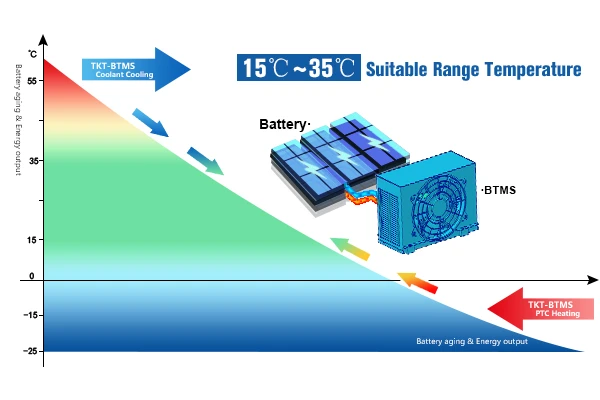

Temperature Is Where Things Get Complicated

Heat damage does not announce itself. A battery cycled at 40C instead of 25C loses capacity faster, but the loss is gradual. Maybe 2 percent extra per year. Maybe 5 percent. Hard to notice month to month. After three years, the battery that should have 90 percent capacity left has 70 percent. Nobody connects this to the installation location, the lack of ventilation, the summer months running loads in an enclosed compartment.

The Arrhenius equation governs this degradation. Rough rule of thumb: reaction rates double for every 10C increase. Battery manufacturers know this. Their cycle life ratings assume 25C testing. The fine print might mention this. Usually it does not.

Real installations rarely maintain 25C. A battery compartment in a vehicle sitting in summer sun easily hits 35-40C ambient before any load is applied. Add discharge heating on top of that. Cell temperatures during heavy discharge can reach 50C or higher in poorly ventilated installations.

This matters more for longevity than for instantaneous load handling. A battery will still deliver its rated current at elevated temperatures, at least until thermal protection triggers. But every high-temperature cycle chips away at total lifespan. An installer saving $50 by skipping ventilation might cost the customer $500 in early battery replacement.

Cold weather creates a different problem. LiFePO4 discharge performance drops maybe 20-30 percent at minus 20C, but the cells survive fine. Charging below freezing causes permanent damage through lithium plating. Any battery without low-temperature charge protection is a liability in cold climates. This should be a baseline feature but budget products sometimes skip it.

The lithium plating issue is worth understanding because it is both serious and invisible. When you charge a LiFePO4 cell below about 0C, lithium ions moving from cathode to anode cannot intercalate properly into the graphite structure. Instead, metallic lithium deposits on the anode surface. This lithium is permanently lost from the charge cycle. The cell loses capacity. Worse, the metallic lithium can form dendrites that grow toward the cathode, eventually causing internal shorts.

A single cold charge might cost 1-2 percent capacity. A winter of careless charging in an unheated garage could destroy 15-20 percent of the battery. The damage is cumulative and irreversible. Users often do not connect the capacity loss to the cold charging because the correlation is not obvious. They charged the battery, it seemed to work, and months later the capacity is lower than expected.

Quality BMS units include temperature sensors on the cells and will refuse to accept charge current below a threshold, usually 0C or 5C. The battery appears dead when cold, which confuses users, but this is the BMS doing its job. Budget BMS units sometimes skip this protection or use cheap temperature sensors that read inaccurately. Some put the sensor on the BMS board itself rather than on the cells, measuring the wrong temperature entirely.

The 48V Advantage Is Really About Current

Comparing 48V to 12V or 24V systems for the same power delivery shows why higher voltage wins for serious loads.

A 5kW load at 12V needs 417 amps. At 48V, the same load needs 104 amps. Cable sizing, connector ratings, fuse costs, voltage drop calculations all scale with current. The 12V system needs four times the copper cross-section, four times the connector capacity, and generates sixteen times the resistive losses at every connection point.

The resistive loss scaling matters more than people realize. Power dissipated in a resistance equals current squared times resistance. Double the current, quadruple the power loss.

The 12V system at 417A through a 1 milliohm connector drops 0.4 volts and dissipates 174 watts at that single connection point. The 48V system at 104A through the same connector drops 0.1 volts and dissipates 11 watts. The connector might survive 11 watts indefinitely. 174 watts will melt it eventually.

This cascading effect explains why 12V systems fail at high power even when every component is supposedly rated for the current. Each connector, each fuse holder, each terminal adds a bit of resistance. The heat from all those resistances accumulates. One connection runs slightly hotter than the others, its resistance increases, it runs hotter still. The weakest connection fails first, but the root cause was the decision to run too much current through too many resistance points.

For low power applications, 12V works fine. For anything over 2-3kW sustained, 48V architecture stops being optional. This is why golf carts, forklifts, marine systems, and serious off-grid solar all standardized on 48V decades ago. The physics just works better.

48V also sits below the 60V safety threshold that triggers additional regulatory requirements in most jurisdictions. Not a coincidence. System designers specifically chose 48V to maximize voltage while staying under the threshold where more expensive safety measures become mandatory.

What Actually Matters When Buying

Skip the headline specs. Every manufacturer claims 100A continuous, 200A peak, 3000 plus cycles. These numbers mean different things to different companies and testing conditions make comparison meaningless.

The 3000 cycle claim is especially misleading. That number comes from cell-level testing under laboratory conditions. 25C constant temperature, 1C charge and discharge, 100 percent to 0 percent depth of discharge. No partial cycles, no temperature variation, no extended storage at high or low charge states. Real world usage differs in every single parameter. A battery that hits 3000 cycles in the lab might manage 1500-2000 cycles in demanding field conditions. Or it might exceed 4000 cycles in gentle applications with controlled temperatures and shallow cycling. The number on the spec sheet is a starting point for estimation, not a guarantee.

Instead of headline specs, focus on questions most buyers do not ask:

What BMS brand and model? Some manufacturers will answer this. Many will not. Known BMS brands like JBD, Daly, Overkill, and Batrium at least have track records. Anonymous BMS boards could be anything.

What is the pack internal resistance? Not cell resistance. Pack resistance measured at the terminals. Lower is better for load handling.

What is the BMS continuous current rating at 40C ambient? The 25C rating is mostly useless for real installations.

What cell grade? A-grade cells meet full manufacturer specs. B-grade cells failed some parameter. Both work. B-grade just has more unit-to-unit variation. Budget batteries use B-grade stock almost universally. This is not necessarily bad, but pack-level testing matters more with inconsistent cells.

Is there pack-level testing data or just cell datasheets? Cell data tells you what the cells can do in isolation. Pack data tells you what this specific product actually delivers.

Does the warranty cover capacity degradation? Many warranties only cover complete failure. A battery that loses 40 percent capacity in two years might not qualify for warranty replacement if it still turns on and delivers some current.

Most manufacturers will not answer these questions. That tells you something too.

Parallel Operation Gets Messy

Running multiple batteries in parallel sounds simple. Two 100Ah batteries equal 200Ah capacity and 200A current capability. Real installations get complicated.

Parallel batteries need matched internal resistance to share current evenly. If one battery has 35 milliohms and its partner has 50 milliohms, the lower resistance unit carries more current, runs hotter, and ages faster. After a year of uneven loading, the capacity mismatch gets worse. The weaker battery becomes a bottleneck for the whole system.

The math here is straightforward but often ignored. Two resistors in parallel share current inversely proportional to their resistance. A 35 milliohm battery paralleled with a 50 milliohm battery does not split current 50/50. The lower resistance battery carries about 59 percent of the load. At 150A total draw, that is 88A through one battery and 62A through the other. The harder-working battery heats up more, which increases its resistance, which would normally balance the current sharing except that its BMS might hit thermal limits first, shutting that unit down and dumping full load onto its partner. Bad outcome.

Buying two batteries from the same manufacturer, same model, same production batch improves the odds of good matching. Buying from different vendors or different production runs is gambling on compatibility.

Cable lengths between parallel batteries and the common bus also affect current sharing. An extra six inches of cable run adds enough resistance to skew the distribution measurably. Proper parallel installations use identical cable lengths to each battery. Many installers do not bother because the difference seems trivial. Over years of cycling, trivial differences compound.

The right way to wire parallel batteries is a star configuration with equal length cables radiating from a central bus bar to each battery. The common approach of daisy chaining batteries in series creates progressively longer paths to the batteries at the end of the chain. This causes those end batteries to work less hard during discharge and receive less charge current, leading to imbalanced aging.

BMS units in parallel batteries do not coordinate. Each BMS monitors only its own pack. If one battery BMS trips on over-temperature while the others keep running, the remaining batteries suddenly carry the full load, potentially overloading them too. Cascading failures happen. The triggering battery might have been fine. Its BMS might just have a lower temperature threshold than its partners.

High-end systems use a master BMS coordinating multiple slave units over CAN bus. Victron and some other brands offer this. It solves the coordination problem but costs more and limits vendor choices. Most consumer installations just parallel separate batteries and hope for the best. Usually this works. When it fails, the failure mode can be expensive.

Realistic Expectations

A quality 48V 100Ah LiFePO4 battery from a reputable manufacturer handles 80-100A continuous discharge in reasonable conditions. Reasonable means ambient temperature under 30C, adequate ventilation, properly sized cabling, and matched components.

Push beyond those conditions and results vary. High ambient temperatures reduce effective capacity. Poor ventilation accelerates degradation. Undersized cables create voltage drop that looks like battery problems. Mismatched parallel strings cause uneven aging.

Most problems attributed to batteries trace back to installation or system design. The battery gets blamed because it is the most expensive component that failed. Often it is the cheapest component that caused the failure.

The cabling issue deserves more attention than it gets. A 48V 100A system needs substantial copper. At 10 feet cable length, 4 AWG wire drops about 1.3 volts under 100A load. That is 130 watts of loss, all converted to heat in the cables. Use 2 AWG and the drop falls to 0.8 volts. The battery appears to have better voltage regulation with thicker cables, but the battery is exactly the same. The improvement comes from removing a resistance that was never part of the battery specification.

Connector quality matters similarly. Anderson SB50 connectors are rated for 50A, but the contact resistance at that current creates meaningful voltage drop. SB175 connectors handle 100A with lower resistance. Ring terminals crimped with the wrong tool create high-resistance joints that heat up under load. Proper hydraulic crimping with appropriate dies makes reliable connections. Hand crimpers often do not.

Buying a better battery helps, but not as much as designing the installation correctly. A $600 battery in a well-ventilated compartment with proper cabling outlasts a $1200 battery crammed into an unventilated cabinet with undersized wires.

That said, the battery market quality spread is wider than it should be. The price range for 48V 100Ah LiFePO4 batteries runs from under $300 to over $1000. The $300 unit probably works fine for light duty. Whether it survives heavy continuous loads is genuinely uncertain. The $1000 unit probably has better BMS components, better cell matching, and better pack construction. Probably.

The frustrating reality: it is hard to know what you are actually buying. Spec sheets are marketing documents. Reviews come from people who have owned the battery for three months, not three years. Failure data stays with manufacturers. Making informed decisions requires either industry connections or a willingness to gamble.

There is an asymmetry in how battery information flows. Manufacturers know exactly how their products perform because they handle warranty claims. They know which batches had problems, which applications cause early failures, which BMS firmware versions had bugs. This information does not reach buyers. A product might have a 15 percent field failure rate in high-discharge applications and buyers would never know unless they happened to be in that 15 percent.

Review sites and YouTube channels test batteries, but the tests rarely stress the product anywhere near its limits. Running a 100A discharge for 60 seconds and declaring the battery can handle 100A is meaningless. Running 100A for an hour at 35C ambient would be informative. Nobody does that because it is boring to watch and hard to set up.

For critical applications, buying from manufacturers with long track records and responsive warranty service provides some insurance. Battle Born, RELiON, Victron have been around long enough that their failure modes are known. This does not mean their products are perfect. It means problems get talked about and sometimes fixed.

For less critical applications, cheaper batteries represent acceptable risk. A golf cart battery that fails after two years instead of five is annoying but not dangerous. A solar backup battery that cannot sustain full load during a power outage has more serious consequences. A marine battery that quits five miles from the dock creates genuine safety problems.

Match the battery choice to the stakes involved.

One More Thing About Spec Sheets

Specification sheets in this industry serve marketing more than engineering. A battery rated for 100A continuous discharge at 25C ambient with forced air cooling tells you nothing about performance in a sealed compartment at 35C. The test conditions that generate the published numbers rarely match field conditions.

Some manufacturers are more honest than others. Victron publishes detailed derating curves. Their specs tell you what to expect at different temperatures and discharge rates. Most budget brands publish best-case numbers and leave buyers to discover the limits themselves.

The cycle life ratings deserve particular skepticism. Testing to 80 percent capacity retention under laboratory conditions produces a number. Whether that number means anything for a specific application depends on how closely that application matches the test conditions. Usually it does not match closely at all.

When evaluating spec sheets, look for completeness rather than impressive numbers. A manufacturer that publishes test conditions, temperature coefficients, and derating curves probably tested their product seriously. A manufacturer that lists only headline specs probably did not.