What Causes Lithium Battery Fires?

The lithium battery sitting in a pocket right now contains enough chemical energy to start a fire that water cannot extinguish. Most people know this vaguely, the way they know cigarettes cause cancer or that seatbelts save lives. The knowledge exists without weight. Billions of these devices ship annually, get dropped, overheated, forgotten in hot cars, thrown in trash cans, and the vast majority never ignite. So people assume the danger is theoretical. The physics says otherwise.

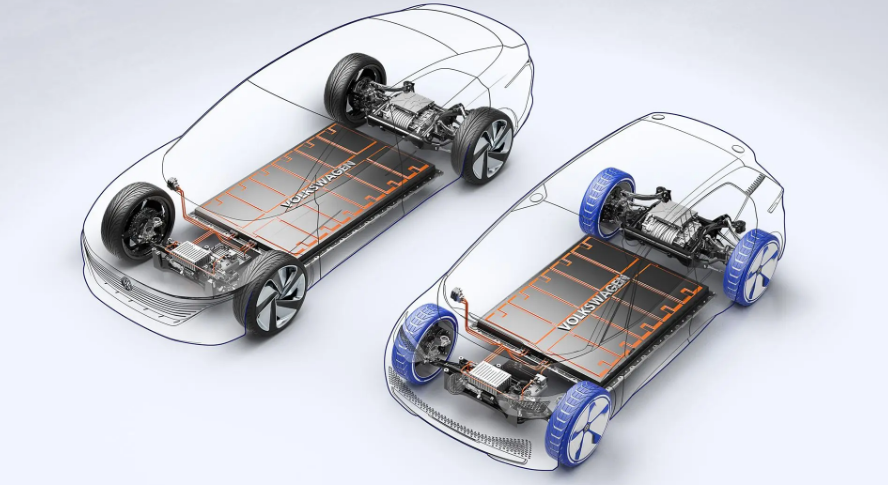

Modern lithium-ion battery cells power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles, storing enormous energy in compact packages.

A lithium-ion cell is a bomb with good manners. The electrochemistry holds roughly 200 watt-hours per kilogram, four times what lead-acid batteries manage and ten times what nickel-cadmium could deliver. That energy wants out. Two electrodes sit millimeters apart, separated by a plastic film thinner than a grocery bag, bathing in a solvent that burns like lighter fluid. The engineering keeping this arrangement stable deserves respect. The engineering fails often enough to fill warehouses with burned-out wreckage.

Nobody counts the warehouses.

The Runaway Problem

Thermal runaway is the term of art. The phrase sounds clinical, bureaucratic even. What happens is not clinical. Picture a cell phone battery heated past 150 degrees Celsius. The protective coating on the negative electrode starts decomposing. This decomposition releases heat. The heat accelerates decomposition. The plastic separator between electrodes begins softening, shrinking. If it tears or melts through, the electrodes touch. A dead short. The entire stored energy of the cell dumps through that contact point in seconds. Temperatures hit 600 degrees. The aluminum casing ruptures. Flammable vapor jets out and ignites.

When thermal runaway occurs, temperatures can exceed 600°C as the battery's chemical energy releases uncontrollably.

In a single cell, this produces a brief violent flare. In a battery pack with thousands of cells packed tight, the heat from one failing cell cooks the neighbors. They fail too. Then their neighbors. A Tesla battery pack contains over 7,000 cells. Work out the multiplication yourself.

The chemistry causing this cannot be designed away because the chemistry is the product. Lithium batteries store so much energy precisely because they contain reactive materials held in unstable configurations. The organic carbonate solvents used as electrolyte catch fire easily. No commercially viable alternative exists after thirty years of searching. The nickel-rich cathodes that enable 300-mile driving range decompose at high temperature and release oxygen. A battery generating its own oxidizer while burning is not a malfunction. The materials are doing what the materials do.

Battery engineers have added sensors, cooling systems, fireproof barriers between cells, software that monitors temperature and shuts down charging if anomalies appear. These measures help. A modern EV battery is harder to ignite than the laptop batteries of 2006. But harder is not impossible, and the number of batteries in circulation has grown by orders of magnitude. The absolute count of fires rises even as the rate per battery falls.

When the Wrapper Breaks

The vulnerability that matters most is physical. That separator membrane, the thin plastic keeping electrodes apart, measures about 20 microns. A human hair runs 70 microns. Manufacturing this film at scale, coating it evenly, winding it into cells without microscopic tears or wrinkles, then expecting it to survive years of thermal cycling and mechanical stress, is genuinely impressive engineering. The failure rate is low.

Low is not zero. Low never means zero.

A battery crushed in a car accident, punctured by a nail, dented by a drop, can fail immediately or weeks later. The damage creates a weak point. Charging cycles stress the weak point. Internal pressure from gas buildup stresses it further. Eventually the membrane tears at the damage site and the electrodes touch. The owner may not connect the fire in the garage to dropping the laptop six months earlier.

Recycling facilities face significant fire risks when lithium batteries enter processing streams concealed in discarded electronics.

Waste facilities see this constantly. Recycling operations run conveyor belts, sorting screens, compactors. A lithium battery concealed in a discarded laptop enters this machinery and gets crushed. Material recovery facilities have reported hundreds of fires from batteries that should never have been in the general recycling stream. The facilities install detection systems, train staff, add fire suppression. Fires continue because consumers throw batteries in recycling bins and garbage cans without thinking twice. The infrastructure for handling these devices at end-of-life barely exists.

Factory Ghosts

Samsung lost five billion dollars on the Galaxy Note 7. The recall involved 2.5 million devices. Investigation found two separate manufacturing problems at two different battery suppliers. Neither problem was visible to standard quality inspection. The defects existed at scales below the resolution of the testing equipment.

This episode showed something that does not appear in marketing materials. At production volumes measured in billions of cells per year, defect rates in parts per million still yield thousands of flawed units reaching consumers annually. A contamination particle invisible to the naked eye, embedded in electrode coating during manufacturing, creates a weak point that may take years to develop into a short circuit. A slight misalignment during cell assembly leaves a stress concentration that accumulates damage with each charge cycle. These cells pass every quality check and ship to customers who have no way to know they hold a future failure.

Battery manufacturing requires cleanroom conditions rivaling semiconductor fabrication

The industry response has been to tighten manufacturing tolerances, add inspection steps, improve cleanroom standards. These efforts have worked in the sense that defect rates have fallen. They have not worked in the sense that defect rates have reached zero, which is the only rate that prevents fires entirely. The math is stubborn. Multiply a tiny failure rate by an enormous production volume and the product is still a meaningful number of fires.

Zero defect manufacturing may be impossible at current production scales. Certainly no battery manufacturer has achieved it. Market forces push the other direction anyway. Consumers want cheaper batteries. Cheaper means faster production lines, less inspection time per unit, thinner margins for suppliers who cut corners to win contracts. The Galaxy Note 7 batteries came from suppliers competing on price.

Charging in the Dark

The charger matters more than most users realize. A lithium battery requires specific voltage and current profiles throughout the charging cycle. The battery management system communicates with the charger, reporting cell voltage, temperature, and state of charge. The charger adjusts its output accordingly. This dance continues for hours until charging completes.

A counterfeit charger, purchased for eight dollars on an overseas marketplace, may lack communication capability entirely. It applies fixed voltage regardless of what the battery needs. Or it communicates using protocols that do not quite match the battery's expectations, causing the system to misjudge state of charge. Or its voltage regulation is sloppy, allowing current spikes that the battery management system does not catch in time.

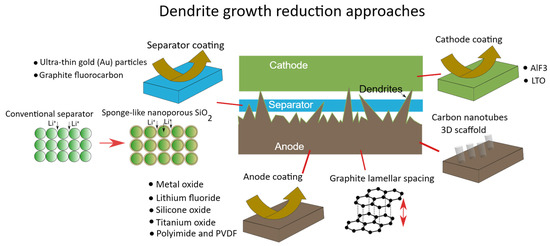

Proper charging equipment and protocols are essential for preventing lithium plating and the dangerous dendrites that follow.

The failure mode here is lithium plating. Push too much current into a lithium battery too fast, especially at low temperature, and the lithium ions arriving at the negative electrode cannot insert into the graphite structure quickly enough. They deposit as metallic lithium on the electrode surface instead. This plated lithium is extremely reactive. Worse, it tends to grow in needle-like formations called dendrites that push through the separator toward the opposite electrode. A dendrite that bridges the gap creates an internal short circuit with consequences identical to physical damage.

Cold weather charging without battery preheating causes the same problem through different mechanism. The kinetics of lithium insertion slow dramatically below 10 degrees Celsius. Charging at normal rates in cold conditions plates lithium even with proper equipment. Electric vehicle owners who plug in immediately after parking in winter, eager to top up before the next trip, may be creating damage that manifests weeks later when conditions change.

Heat Kills, Cold Maims

A phone left on a car dashboard on a summer afternoon experiences interior temperatures approaching 80 degrees Celsius. This is thermal abuse. The battery does not catch fire, usually, but the chemistry degrades at accelerated rates. The protective layer on the negative electrode thickens. The electrolyte decomposes. The separator material creeps under mechanical stress from electrode expansion. Each hot soak shortens battery life and reduces the margin before thermal runaway conditions.

The cumulative nature of heat damage makes it invisible until too late. The battery loses capacity gradually, which the user notices as shorter runtime. The battery also loses thermal stability gradually, which the user cannot notice at all until the day conditions align for failure. An aged battery with accumulated heat damage sits closer to the edge of the cliff than a new battery. The same abuse that a new cell survives may push an old cell over.

Humidity attacks through different pathway. Lithium reacts violently with water. A battery seal compromised by age or damage admits moisture that reacts with internal lithium compounds, producing gas and heat. Batteries stored in damp basements or humid garages accumulate this damage invisibly. The swelling that sometimes precedes failure is gas pressure from these reactions.

The Aging Cliff

Every lithium battery degrades from the moment of manufacture. The degradation follows predictable patterns that battery scientists have mapped in detail. Capacity fades as side reactions consume active lithium. Internal resistance rises as electrode surfaces accumulate decomposition products. The rate of degradation depends on temperature, charge level, and cycling patterns, but the direction is always the same.

Batteries get worse. Always.

The safety implications are less discussed. An aged battery has higher internal resistance, meaning it generates more heat during normal operation. An aged battery has a thinner, more brittle separator, meaning it tolerates less mechanical stress. An aged battery has accumulated gases that increase internal pressure. All of these changes reduce the margin before thermal runaway.

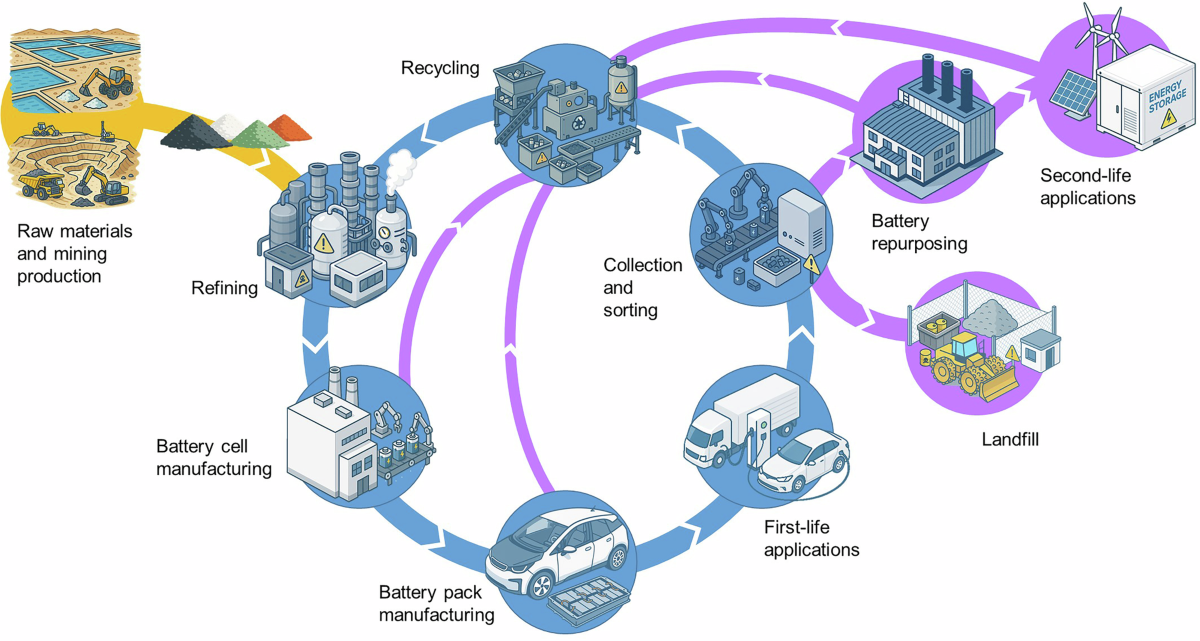

Batteries reaching end-of-life have unknown degradation histories, making safe handling at recycling facilities increasingly difficult.

The batteries reaching recycling facilities today were manufactured years ago under standards that have since improved. They have experienced years of cycling, heat exposure, potential physical abuse. Their condition cannot be assessed from external inspection. The handling procedures adequate for new batteries may not suffice for aged batteries of unknown history. Nobody tracks individual battery histories through the waste stream.

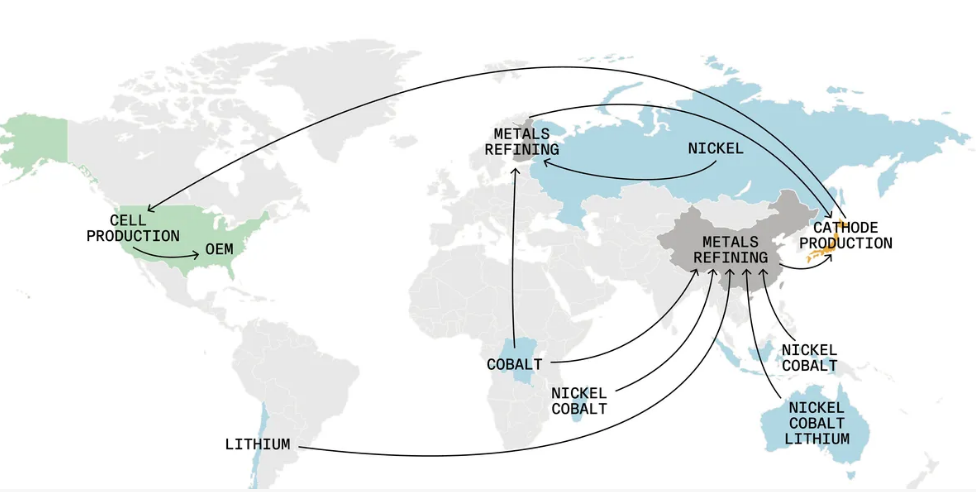

The Mineral Question

Lithium batteries contain cobalt, lithium, nickel, manganese, and graphite in forms that took considerable energy to refine. Cobalt supply depends heavily on mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo with well-documented labor and environmental problems that periodically generate headlines and corporate sustainability pledges without fundamentally altering sourcing patterns. Lithium extraction from brine ponds in Chile and hard rock deposits in Australia cannot scale fast enough to meet projected demand from electric vehicles alone, never mind grid storage and consumer electronics. These materials have strategic significance that policymakers discuss with increasing urgency, commissioning reports and forming committees while production continues outpacing domestic supply development.

Critical minerals like cobalt and lithium require energy-intensive extraction, making recycling essential for sustainable battery production.

Every battery fire at a recycling facility destroys materials that should have been recovered. The circular economy concept, where end-of-life products supply materials for new production, cannot function when fires incinerate the feedstock. Collection rates for consumer batteries remain pathetically low, meaning most end-of-life batteries enter waste streams where they either cause fires or reach landfills where their materials disperse permanently. Building the infrastructure for proper collection and recycling requires investment that the economics have not justified, partly because the externalities of fire damage and lost materials do not land on battery producers.

Rules Written for Different Problems

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act dates to 1976. Commercial lithium batteries did not exist. The hazardous waste framework applies to lithium batteries through general characteristics of ignitability and reactivity, not through categories designed for electrochemical devices. The fit is awkward.

Household batteries receive categorical exemption from hazardous waste requirements regardless of chemistry. A consumer can legally throw lithium batteries in household trash.

Legally. Into a truck that compacts its contents.

The exemption reflects enforcement practicality, not safety assessment. The fire risk from a lithium battery in a garbage truck is identical whether the generator was a business subject to regulation or a household exempt from it.

Transportation regulations classify lithium batteries as hazardous materials, imposing packaging requirements. Enforcement concentrates on commercial shipments. Individual consumers mailing batteries through retail carriers often ship illegally without knowing or caring. The gap between regulatory intent and practical effect widens as battery prevalence grows and enforcement resources stay flat.

What Works

Terminal isolation prevents external short circuits. Covering battery terminals with tape before storage or disposal blocks current paths through accidental contact with metal objects or other batteries. The practice takes thirty seconds and costs nothing. Batteries continue arriving at recycling facilities with terminals exposed.

Temperature control during storage extends battery life and reduces fire probability. Climate-controlled warehouses for batteries awaiting recycling cost money to operate. Fires at those facilities cost more.

The math should be obvious. Many facilities skip it anyway.

Proper charging equipment and practices prevent plating damage. Using manufacturer-specified chargers, avoiding charging at temperature extremes, discontinuing use of swollen or damaged batteries, keeping charging devices away from bedding and other flammables. Each recommendation sounds trivial. Each gets ignored daily by millions of users.

Deposit systems for batteries, similar to beverage container deposits, create economic incentives for return. These systems function in jurisdictions that have implemented them. Extended producer responsibility regulations shift end-of-life costs to manufacturers, who then have incentive to design for recyclability and fund collection infrastructure. These policy tools exist. Their adoption remains spotty.

The Solid State Mirage

Battery manufacturers have promoted solid-state electrolytes as the solution to flammability for years. Replace the flammable liquid electrolyte with a solid lithium conductor and one fire risk disappears. Laboratory demonstrations have achieved impressive results. Commercial production has not followed.

Solid-state battery technology promises safer energy storage

The technical obstacles are not minor refinements away from solution. Solid electrolytes struggle to maintain low-resistance contact with solid electrodes across surfaces that expand and contract during cycling. Lithium metal anodes, which solid electrolytes enable, form dendrites that propagate through grain boundaries in the solid material. Manufacturing processes achieving laboratory quality do not obviously transfer to mass production at competitive cost.

The timeline for solid-state batteries reaching consumers in volume has slipped repeatedly. Announcements of breakthroughs generate headlines and support stock prices. Products reaching consumers have not materialized at scale. Skepticism about promised timelines is warranted given the history.

The Accumulating Problem

Global lithium battery production exceeded 1,000 gigawatt-hours in 2023 and continues growing rapidly to meet electric vehicle and grid storage demand. Each new battery represents a future disposal challenge. The infrastructure for collecting, transporting, and recycling these batteries at end-of-life does not exist at anything approaching adequate scale.

As electric vehicle adoption accelerates, the gap between battery production and recycling capacity continues to widen.

The gap between battery production and recycling capacity widens annually. Batteries entering waste streams cause fires at material recovery facilities. Batteries reaching landfills waste critical materials and create long-term environmental liability. The circular economy remains conceptual while the linear economy generates increasing volumes of hazardous waste.

Policy response has lagged production growth. The fires continue. The material losses continue. The statistics accumulate without generating political urgency sufficient to fund the required infrastructure. At some point the accumulation may trigger response. The number of fires that must occur before that point remains unknown.

Lithium batteries will catch fire sometimes. The materials inside them make this inevitable under adverse conditions. Production scale means the absolute count of fires stays significant even if rates improve. Collection and recycling infrastructure will remain inadequate until pressure forces investment. Whether that pressure comes from foresight or from damage severe enough to demand response depends on decisions that nobody seems eager to make. So far, the fires have not been enough.