Smartphones, laptops, tablets, wireless earbuds, smartwatches, portable speakers, e-readers, handheld gaming consoles, electric toothbrushes, shavers. Now walk outside. Electric scooters locked to bike racks. Teslas humming through intersections. A delivery robot navigating the sidewalk. Behind the walls of that apartment building, home battery systems storing solar energy. Construction workers on a nearby site running cordless drills and saws. A medical technician wheeling portable monitoring equipment into an ambulance.

All of them run on lithium.

The ubiquity happened so gradually that most people never noticed the transition. One decade ago, lithium batteries powered phones and laptops. Now they undergird the entire infrastructure of daily life in developed economies, and increasingly in developing ones too. .

BloombergNEF documented that global demand crossed one terawatt-hour in 2024. Manufacturing capacity now exceeds twice that figure. The scale signals a fundamental restructuring of how civilization stores and deploys energy. The camcorder batteries Sony commercialized in 1991 have evolved into the foundation of electric transportation, renewable energy systems, and the portable computing revolution that reshaped human communication.

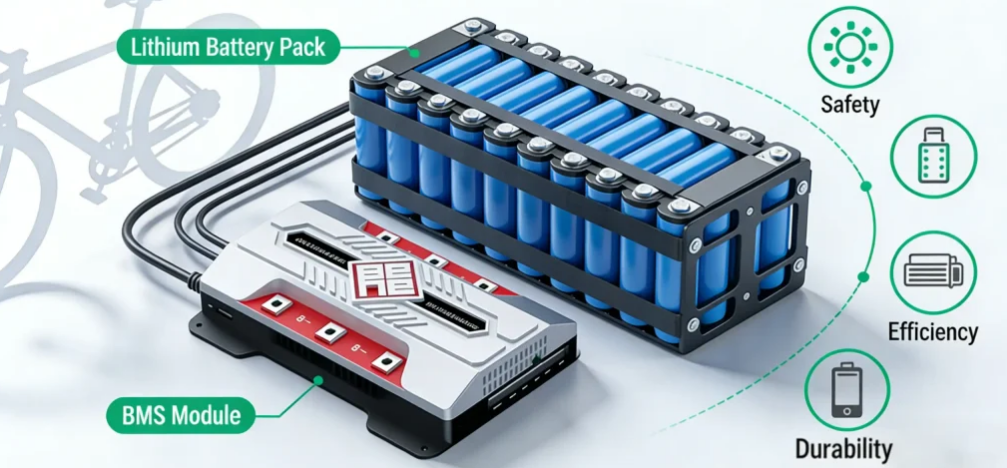

Modern lithium battery cells

The Chemistry That Won

Lithium sits third on the periodic table. Lighter than everything except hydrogen and helium. Smallest atomic radius of any metal. Most negative electrode potential at -3.04 volts. These facts get repeated in every article about battery technology, usually accompanied by breathless proclamations about lithium's destiny to revolutionize energy storage.

The reality is messier.

Lithium won partly through technical merit and partly through historical accident. Sony needed a rechargeable battery for camcorders in 1991. Their engineers chose lithium cobalt oxide. That chemistry happened to work well enough for consumer electronics, so manufacturers scaled it. Investment followed success. Competitors entered the market. Prices dropped. The technology improved because money poured in, and money poured in because the technology improved. A virtuous cycle that had as much to do with timing and market dynamics as with lithium's inherent superiority.

Beyond raw energy storage, lithium cells eliminated the memory effect that plagued nickel-cadmium technology. Users of older rechargeable batteries developed elaborate discharge rituals, running devices until completely dead before recharging to preserve capacity. Lithium tolerates partial charging without degradation. Monthly self-discharge rates of 1.5-2% mean a stored battery retains most of its charge after a year, whereas nickel-metal-hydride alternatives might lose 30% in a single month sitting on a shelf.

The nominal cell voltage of 3.6-3.7 volts creates additional design advantages. Lead-acid cells produce 2.0 volts; nickel-based cells generate 1.2 volts. Achieving the 400+ volt systems required for electric vehicle powertrains demands fewer lithium cells in series, which reduces connection points, simplifies thermal management, and improves reliability.

Other chemistries existed. Some still do. Nickel-metal-hydride batteries powered early hybrid vehicles and still appear in some applications. Flow batteries offer advantages for grid storage. Sodium-ion technology has attracted serious investment from CATL. None of them gained enough momentum to challenge lithium's dominance, not because they couldn't work, but because they arrived too late to the party. The factories were already built. The supply chains were already established. The engineers had already spent careers optimizing lithium systems.

Path dependence shapes how the industry operates. Battery manufacturers don't pursue the theoretically optimal chemistry. They pursue incremental improvements to existing lithium systems because the infrastructure supports nothing else. When Toyota announces progress on solid-state batteries, they're talking about solid-state lithium batteries. When researchers publish papers on improved anodes, they mean anodes for lithium cells. The entire field orbits a single element not because alternatives are impossible but because the installed base creates its own momentum.

The term "lithium battery" encompasses a family of related chemistries, each with distinct characteristics suited to particular applications.

Lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO₂, commonly abbreviated LCO) packs the highest energy density into minimal volume. Smartphones and laptops use LCO because fitting the battery into tight spaces takes priority over cost or longevity. The chemistry dominates consumer electronics for this reason alone.

Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄, or LFP) sacrifices some energy density for substantially improved thermal stability and cycle life. These cells resist thermal runaway more effectively and tolerate 2,000-3,000 charge cycles before significant degradation—roughly twice the lifespan of cobalt-based alternatives. Chinese manufacturers, particularly CATL and BYD, have championed LFP technology. The chemistry also avoids cobalt's supply chain complications and the ethical concerns surrounding artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Chemistry selection involves genuine engineering trade-offs rather than marketing distinctions. A battery optimized for smartphone performance would fail in grid storage applications, while a chemistry designed for 20-year stationary service would prove impractical in weight-sensitive portable electronics. The market supports multiple chemistries because different applications impose different constraints.

Phones and Laptops: Where the Money Came From

Consumer electronics funded the lithium battery industry's adolescence. Smartphones alone created demand sufficient to justify massive manufacturing expansion. Statista's 2024 market analysis documents over 6.9 billion active smartphones globally, each containing a lithium polymer cell typically ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 milliamp-hours. Multiply by billions of devices sold annually and you get a market large enough to support dedicated battery factories employing thousands of workers.

The engineering constraints are brutal. Batteries must fit into ever-thinner chassis. They must survive years of daily charging. They must operate across temperature extremes—frozen Canadian winters, Arizona summers, the interior of a parked car in direct sunlight. They must do all this while users demand longer battery life with each generation, even as screens get brighter, processors get faster, and 5G radios consume more power than their predecessors.

Smartphones and portable devices

Laptop batteries face similar pressures with larger capacities. Gaming laptops might pack cells exceeding 90 watt-hours, the maximum allowed on commercial aircraft without special documentation. Ultrabooks achieve 12-hour runtimes through a combination of larger batteries and ruthless power optimization in processors and displays. The improvements arrive steadily, percentage points per year, invisible to users who notice only that their new phone lasts roughly as long as their old one despite having a brighter screen and faster processor.

Wearable devices push miniaturization further. The Apple Watch Series 9 operates for a full day on a battery under 400 milliamp-hours—roughly one-tenth the capacity of a budget smartphone. Wireless earbuds function with batteries measured in tens of milliamp-hours, sustaining hours of audio processing and Bluetooth transmission from packages small enough to fit inside human ear canals. No alternative chemistry approaches these power densities at such scales.

Digital cameras reveal an underappreciated lithium advantage: burst mode shooting. Modern mirrorless cameras capture dozens of high-resolution images per second, each requiring sensor readout, image processing, and storage operations consuming substantial current. Lithium cells deliver this power without the voltage sag that afflicts other chemistries under load.

Most coverage skips quickly to electric vehicles. Consumer electronics are mature applications where lithium batteries work without drama. The engineering challenges are real but incremental. No one expects dramatic breakthroughs in smartphone battery technology.

Electric Vehicles Changed Everything

The story that matters starts around 2008, when Tesla delivered its first Roadster.

Electric cars existed before Tesla. They existed before gasoline cars—electric vehicles outsold internal combustion in America at the turn of the twentieth century. Detroit Electric, Baker, and dozens of other manufacturers produced battery-powered automobiles for urban customers who valued quiet operation and easy starting over the range and refueling speed of gasoline. The internal combustion engine won that competition through a combination of falling fuel prices, improved roads enabling longer trips, and the electric starter that eliminated the dangerous hand-cranking that had made gasoline cars inconvenient.

Modern lithium-powered EVs trace their lineage to that Roadster, a converted Lotus Elise stuffed with laptop batteries. The car was expensive, impractical, and produced in tiny numbers. It also proved something important: lithium batteries could move a car fast enough and far enough to matter. Range anxiety was manageable. Performance exceeded expectations. The technology worked.

What followed reshaped the global automotive industry.

Tesla's Model S arrived in 2012 with a 85 kilowatt-hour battery pack and a range exceeding 200 miles. The car won Motor Trend's Car of the Year and demonstrated that electric vehicles could compete with luxury sedans on performance and refinement, not merely environmental credentials.

By 2020, every major automaker had announced electrification plans. By 2024, electric vehicles had captured significant market share in China, Europe, and increasingly in North America.

Electric vehicles

Battery pack sizes grew from the Roadster's 53 kilowatt-hours to the Model S's 100 kilowatt-hours and beyond. Ranges extended past 300 miles. Charging infrastructure spread across highway networks. The IEA's Global EV Outlook 2024 documented that over 190 gigawatt-hours of lithium battery capacity entered global vehicle fleets through 2023 alone.

Vehicle batteries must survive 1,000-2,000 complete charge cycles while retaining 80% capacity—eight to fifteen years of typical driving patterns. Operating temperatures range from -40°F in northern winters to 140°F in sun-baked parking lots. The batteries must deliver sustained high-current discharge during acceleration, absorb regenerative braking energy, and survive the vibration, shock, and environmental exposure inherent in automotive service.

The scale of battery consumption staggered industry observers. A single electric vehicle contains battery capacity equivalent to thousands of smartphones. Global EV production consumes more lithium battery capacity than all consumer electronics combined. Automotive applications now drive the industry's direction not because cars are technically more interesting than phones, but because they demand so much more material.

Consider what this means for manufacturing. A smartphone factory might produce millions of small cells annually. An EV battery factory must produce equivalent capacity in cells large enough for automotive use, with quality standards far exceeding consumer electronics, at prices low enough for mass-market vehicles.

Gigafactories

Gigafactories emerged to meet this demand. Tesla's Nevada facility. CATL's sprawling complexes in China. LG's plants in Poland and Michigan. SK Innovation's Georgia operations. Billions in capital investment, supply chains spanning continents, workforces numbering in tens of thousands—all built because electric vehicles require battery production at scales that seemed fantastical a decade ago.

Tesla's 4680 cell format exemplifies ongoing optimization efforts. The larger cylindrical format reduces manufacturing complexity through fewer individual cells per pack, improves thermal management through better surface-area-to-volume ratios, and increases energy density compared to smaller formats. The structural battery pack concept .

Electric bicycles and scooters sparked a parallel revolution in urban transportation, one that receives less attention in Western media than it deserves.

E-bikes use smaller lithium packs, typically 250-750 watt-hours, enabling ranges of 20-50 miles depending on terrain, rider weight, and assistance level. The vehicles extend cycling range and flatten hills, making bicycle commuting practical for people who would otherwise drive. The market grew faster than most analysts predicted, particularly in European cities implementing car-free zones and Chinese urban areas where two-wheeled transportation has always dominated.

The contrast with gasoline alternatives is stark. A 50cc motor scooter weighs several hundred pounds. An electric equivalent achieving similar range might weigh under fifty. The weight reduction transforms handling and storage. Electric scooters fold for apartment storage or public transit connections. They carry up stairs. They fit in car trunks.

The category didn't exist before lithium batteries made it practical. Gasoline engines at this scale are loud, smelly, and require frequent maintenance. Lead-acid batteries would add prohibitive weight. Lithium created the market by making the product possible.

The Grid Storage Gamble

Renewable energy has an intermittency problem. Solar panels generate electricity when the sun shines, not when people need power. Wind turbines spin according to weather patterns uncorrelated with demand. Matching supply to consumption requires either dispatchable backup generation .

Lithium batteries entered this market promising to solve intermittency. The pitch was compelling: store excess solar generation during midday peaks, discharge during evening demand. Smooth out wind variability. Provide grid services like frequency regulation faster than any thermal plant could respond.

Residential solar and battery storage systems

Hornsdale Power Reserve

The Hornsdale Power Reserve in South Australia became the poster child for this vision. Installed in 2017 with 150 megawatts and 194 megawatt-hours of capacity, the facility demonstrated that batteries could stabilize grids and earn revenue doing so. Response times measured in milliseconds outperformed conventional thermal generation by orders of magnitude. The project's commercial success spawned similar installations across multiple continents.

California mandated utility-scale storage. Texas added battery capacity to supplement its wind-heavy grid. Announced projects now measure in gigawatt-hours rather than megawatt-hours.

But grid storage economics remain complicated.

Batteries excel at short-duration applications. Frequency regulation. Peak shaving. Shifting solar generation by a few hours. They struggle with longer duration storage—the kind needed to handle multi-day weather events or seasonal variation in renewable output. A lithium battery system sized to provide four hours of backup costs roughly the same as one providing two hours, per unit of power capacity. But sizing for 24 hours or 72 hours multiplies costs dramatically.

The industry talks constantly about declining battery prices, and prices have indeed fallen substantially over the past decade—from over $1,100 per kilowatt-hour in 2010 to around $140 per kilowatt-hour now. Yet grid-scale storage projects still require subsidies, mandates, or favorable regulatory treatment to pencil out financially. The economic case for lithium batteries in stationary applications depends heavily on specific market structures, electricity pricing regimes, and policy support that varies dramatically by jurisdiction.

Alternative technologies target the gaps that lithium leaves open. Iron-air batteries promise cheap long-duration storage at the cost of lower efficiency and larger footprints. Compressed air systems store energy in underground caverns. Pumped hydro remains the dominant grid storage technology globally, though geography limits new deployments. Whether lithium maintains its position in stationary storage or cedes ground to these alternatives will depend on cost trajectories that remain uncertain.

Residential storage occupies a different niche. Systems like the Tesla Powerwall deploy 5-20 kilowatt-hours of capacity to capture solar generation during peak production hours and discharge during evening demand periods or utility outages. In markets with time-of-use electricity pricing, these systems achieve payback through energy cost arbitrage—charging during low-rate overnight periods and discharging during peak afternoon rates. The economics have shifted enough that payback periods under seven years are achievable in favorable markets.

Industrial and Commercial Applications

Power tools transitioned to lithium over the past fifteen years. Cordless drills, saws, and impact drivers now match or exceed corded performance. Professional contractors work entire shifts on battery power. The transformation happened quietly—tool manufacturers simply stopped making nickel-cadmium versions, and customers upgraded without much thought.

The industrial significance extends beyond runtime. Lithium cells maintain stable voltage output across their discharge curve, delivering consistent torque or cutting speed until nearly depleted. Lead-acid batteries exhibit progressive voltage sag, causing tools to slow as charge depletes. For precision applications like torque-sensitive fastening operations, this voltage stability affects work quality directly.

Medical devices present unique demands. Reliability standards exceed commercial requirements by wide margins. Implantable devices like pacemakers use specialized lithium chemistries engineered for decade-long operation inside human bodies. Portable monitors and infusion pumps rely on lithium cells because alternatives can't match the energy density needed for extended mobile operation.

Spacecraft depend on lithium batteries capable of withstanding extreme conditions

NASA's Mars rovers demonstrate lithium battery reliability under conditions far beyond terrestrial applications. Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance all depend on lithium-ion batteries to power instruments, mobility systems, and communication equipment across Martian temperature swings ranging from -195°F to 70°F. According to NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory mission documentation, Spirit and Opportunity were designed for 90-day missions. Spirit operated for six years. Opportunity for fifteen. Their batteries exceeded design life by factors that testified to both engineering margins and fundamental chemistry robustness.

Military applications span communication equipment, unmanned aerial vehicles, soldier-worn electronics, and electric ground vehicles. The defense sector values power-to-weight ratios with particular intensity since every gram carried by infantry imposes physical costs in fatigue, speed reduction, and operational capability. Tactical radios, night vision devices, GPS equipment, and computing systems increasingly specify lithium cells optimized for reliability across environmental extremes.

What Could Go Wrong

Thermal runaway.

The term sounds technical and abstract until you see videos of electric vehicles engulfed in flames or news reports about aircraft battery fires. Lithium batteries contain flammable electrolytes. Internal short circuits, physical damage, or manufacturing defects can trigger self-sustaining reactions that generate temperatures exceeding 1,000°F. Once thermal runaway begins in one cell, heat propagates to neighboring cells, potentially resulting in fires that prove extremely difficult to extinguish.

The risk is real but manageable. Battery management systems monitor individual cell voltages and temperatures, disconnecting charging or load when parameters exceed safe thresholds. Quality manufacturing minimizes the contamination and defects that cause internal shorts. Thermal barriers between cells slow propagation.

Still, failures happen. Samsung recalled millions of Galaxy Note 7 phones after battery fires. Various e-bike and scooter batteries have ignited in apartment buildings, occasionally with fatal results. Electric vehicle fires attract disproportionate media attention relative to their frequency, but they do occur. The regulatory response continues evolving—transportation rules classify lithium batteries as hazardous materials, airlines restrict battery sizes in checked luggage, and IATA regulations effective January 2026 require lithium-ion cells shipped by air cargo to maintain state of charge not exceeding 30%.

The same high energy density that enables superior performance concentrates more potential energy in each gram of material. Lead-acid batteries might leak acid or generate hydrogen gas during overcharging, but they do not undergo energetic thermal decomposition. The trade-off between performance and safety risk runs through every lithium battery application.

Keeping Batteries Healthy

Batteries age whether you use them or not.

The main factors accelerating degradation are temperature, extreme states of charge, and high current loads. Heat drives chemical side reactions that consume active materials and increase internal resistance. Battery University research summaries indicate that every 10°C temperature increase roughly doubles the rate of capacity-reducing side reactions. Storing or operating batteries at full charge or near empty stresses electrode structures. Fast charging generates internal heat and can cause lithium plating on anodes.

Maintaining lithium batteries between 20% and 80% charge rather than cycling between 0% and 100% can double or triple total lifetime capacity throughput.

Electric vehicle owners face similar considerations at larger scales. Many vehicles offer options to limit charging to 80% for daily use, reserving full charges for long trips. Preconditioning systems warm batteries before fast charging in cold weather, avoiding the lithium plating that degrades capacity. Whether these measures matter enough to justify the inconvenience depends on individual circumstances and how long owners plan to keep their vehicles.

Manufacturers recommend maintaining lithium batteries at 40-50% charge for extended storage, with temperatures between 5°C and 20°C optimal for minimizing calendar aging. Periodic cycling maintains capacity for batteries stored longer than six months.

The Supply Chain Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss

Lithium comes from brine evaporation ponds in Chile and Argentina, or hard rock mining in Australia. Cobalt comes predominantly from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where artisanal mining operations employ children under dangerous conditions. Nickel processing generates significant environmental contamination. Graphite production concentrates in China.

The industry acknowledges these issues while continuing to operate supply chains that depend on them.

Efforts to address the worst abuses exist. Cobalt-free lithium iron phosphate batteries have gained market share partly because they avoid the most problematic supply chains. Recycling programs aim to recover materials from spent batteries, reducing demand for virgin mining. Due diligence requirements push manufacturers to trace materials and avoid the worst sources.

Whether these efforts amount to meaningful change or corporate public relations remains debatable. Demand for battery materials continues growing faster than recycling capacity. New mines open to meet production targets. The fundamental economics favor extracting materials wherever they can be found cheaply, regardless of social or environmental consequences at the extraction sites.

This tension will shape the industry's future at least as much as any technical development. Regulations may tighten. Consumer pressure may increase. Or the world may collectively decide that electric vehicles and renewable energy outweigh the conditions under which their components are produced. The outcome remains genuinely uncertain, and anyone who claims otherwise is either uninformed or selling something.

What Happens Next

Solid-state batteries have been five years away for about fifteen years now.

The technology promises higher energy density, improved safety, and faster charging by replacing liquid electrolytes with solid materials. Every major automaker has announced investments. Startups have raised billions. The potential advantages are real.

The future of energy storage continues to evolve in research laboratories worldwide

So are the manufacturing challenges. Solid electrolytes must maintain contact with electrodes despite volume changes during charging and discharging. Interfaces between solid materials degrade in ways that liquid electrolytes avoid. Production processes that work in laboratories have not yet scaled to factory volumes at competitive costs.

Toyota has promised solid-state batteries in production vehicles since at least 2020. The timeline keeps slipping. QuantumScape went public via SPAC at a valuation reflecting optimistic projections that have not materialized. The pattern suggests that solid-state technology may eventually arrive but probably not on the schedules that press releases announce.

Meanwhile, incremental improvements to conventional lithium-ion technology continue. Silicon additions to graphite anodes boost capacity modestly. Nickel-rich cathodes increase energy density at the cost of reduced stability. Manufacturing efficiencies lower costs. These unglamorous advances may ultimately eclipse the headline-grabbing breakthroughs that perpetually seem just around the corner.

Alternative chemistries may supplement lithium in specific applications. Sodium-ion batteries using abundant sodium rather than geopolitically concentrated lithium offer cost advantages for stationary storage where weight constraints are minimal. CATL and other major manufacturers have announced commercial sodium-ion products. Iron-air batteries promise extremely low costs for long-duration storage applications.

Battery cell prices declined from over $1,100 per kilowatt-hour in 2010 to approximately $140 per kilowatt-hour by 2024. Industry projections suggest continued decreases toward $100 per kilowatt-hour within years. These economics accelerate electric vehicle adoption past price parity with combustion vehicles and improve stationary storage economics to compete with peaking natural gas generation.

The honest answer to what comes next is uncertainty. Lithium batteries will probably remain dominant for at least another decade. They may face competition from sodium-ion in cost-sensitive applications. They may eventually yield to solid-state technology if manufacturing problems get solved. They may continue improving gradually until some discontinuous innovation makes predictions obsolete.

Anyone claiming certainty about battery technology's future is selling something.